‘Ahu ‘ula (The Kalakaua Cape), made by Maria Ena, late Nineteenth Century, red ‘i’iwi feathers, yellow and black ‘o’o feathers, and olona fiber. Department of Anthropology, Smithsonian Institution.

By Karla K. Albertson

WASHINGTON DC – While Americans respect and often reference the history of the United States, they can be surprisingly fuzzy about details. The year 1776 and the 13 colonies may be familiar, but to chart the path to 50 states and a cluster of territories, near and far? That would be a college level class.

As for what happened in 1898? Better sign up for another semester. Or head for the new exhibition in Washington to learn about a period in our history when our democratic government seemed to have imperial ambitions. Exactly why did a country – which rejected English colonialism at its very founding – end up fighting to acquire foreign territories just on the brink of the Twentieth Century?

With the name above the door, the National Portrait Gallery has always spelled out its specialty. The contents are pieces of evidence which can be assembled to tell many stories, in this case a complex era of history. Indeed, painted portraits bring historical characters to life in a unique way – not as the invention of the camera would capture them with perfection – but as their contemporaries regarded their importance.

On view at the National Portrait Gallery from April 28 to February 25 is “1898: US Imperial Visions and Revisions.”

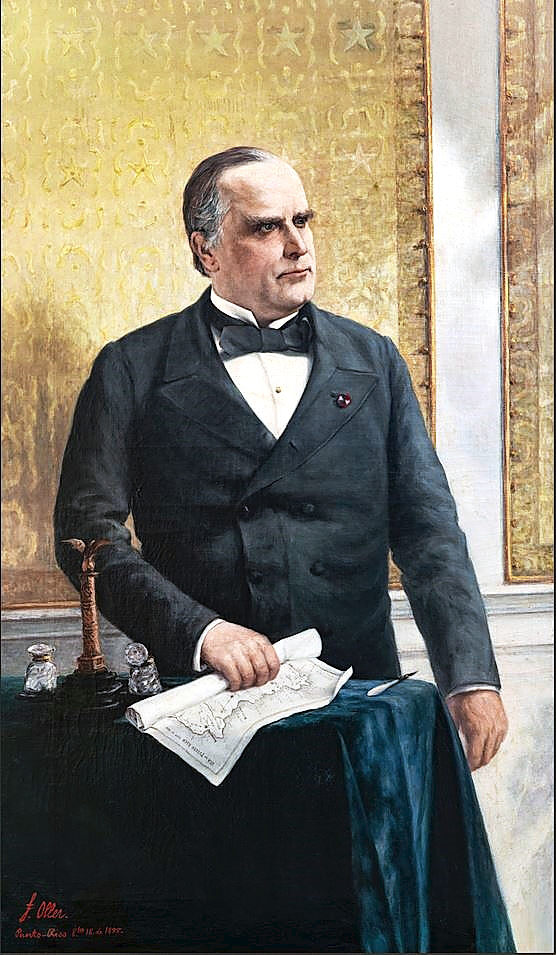

Portrait of President William McKinley by Francisco Oller, oil on canvas, 1898. Collection of Dr Eduardo Perez and family.

—John Betancourt photo

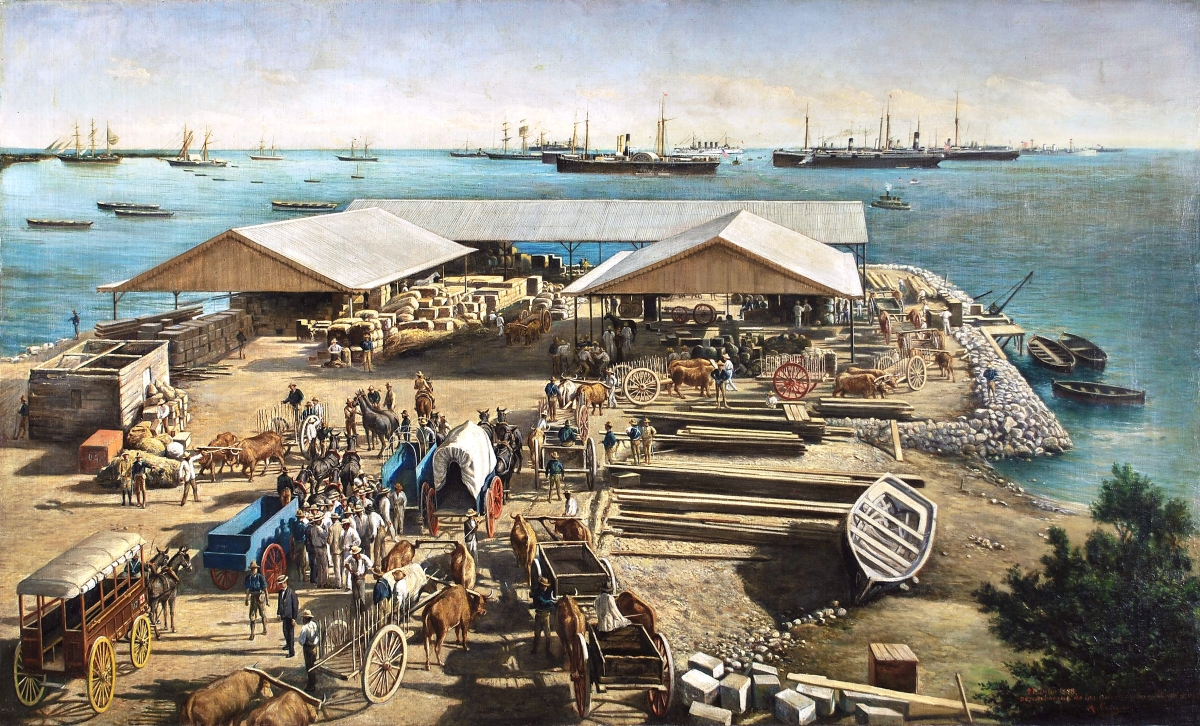

The title was chosen because that crucial year brought the War of 1898, commonly called the Spanish-American War, which was followed by the Philippine-American War of 1899-1913. The United States became involved in international politics, intervening in serious conflicts and revolutions, gaining control of Puerto Rico and Guam, and annexing Hawai’i by Congressional joint resolution.

This is the complex burst of history that co-curators Taina Caragol and Kate Clarke Lemay have brought to life through art. Many of the 94 objects, including 54 portraits, are drawn from the gallery’s permanent collection. But they also traveled to 74 external collections and included works from the archipelagos of Cuba, Guam, Hawaii and the Philippines.

Taina Caragol, curator of painting, sculpture and Latino art and history, spoke with Antiques and The Arts Weekly about how the project came together:

“The Portrait Gallery has historians and art historians because we want to make sure that we shine a light on US history through the means of visual culture – portraiture – and biography. My colleague and co-curator Kate Lemay and I came up with the idea of doing a show on 1898, which was pivotal in the modern history of the country. But we thought, it can’t be only about that – it has to be a show that really grounds what we are calling the ‘War of 1898.'”

“Searchlight on Harbor Entrance, Santiago de Cuba” by Winslow Homer, 1902, oil on canvas. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of George A. Hearn, 1906.

“We’re trying not to refer to it as the ‘Spanish-American War’ because that means it’s very reductive. It makes invisible all the territories that became incorporated into the United States. We need to also address Hawai’i and the Philippines, because all of them became associated to the United States right at that moment, so it’s impossible to talk only about one and not the others – they are interlinked.”

When asked what was in the collection and what was borrowed, the curator replied that, of course, the National Gallery has a very US-centered perspective, so they wanted to discover how the moment looked in the histories of Puerto Rico, Hawaii, the Philippines or Guam. They visited collections in all of the places under discussion as well as Spain and found artwork and documents that could speak to this story. And, said Caragol, “I am delighted that – with my co-curator and our fantastic team – we were able to bring them here on loan.”

When asked about favorites, she knows many visitors will be drawn to the 1891-92 portrait of Queen Lili’uokalani by William F. Cogswell, on loan from the Hawai’i State Archives. The stately figure was the last native ruler of the islands. Forced to abdicate in 1895, she lived to see her country’s annexation by the United States.

Taina Cargol especially cited the 1898 portrait of President William McKinley by Francisco Oller (1833-1917): “I love that portrait because of what the president has in his hands – a map of Puerto Rico dated July 25, 1898, which is the day when the United States landed in Puerto Rico at Guanica. It’s a very significant artwork for that moment, and it’s quite amazing to think that a Puerto Rican painter was a preeminent artist in the late Nineteenth and early Twentieth Century. With the map in McKinley’s hand, the painter is pointing to that moment of transformation his island was experiencing.”

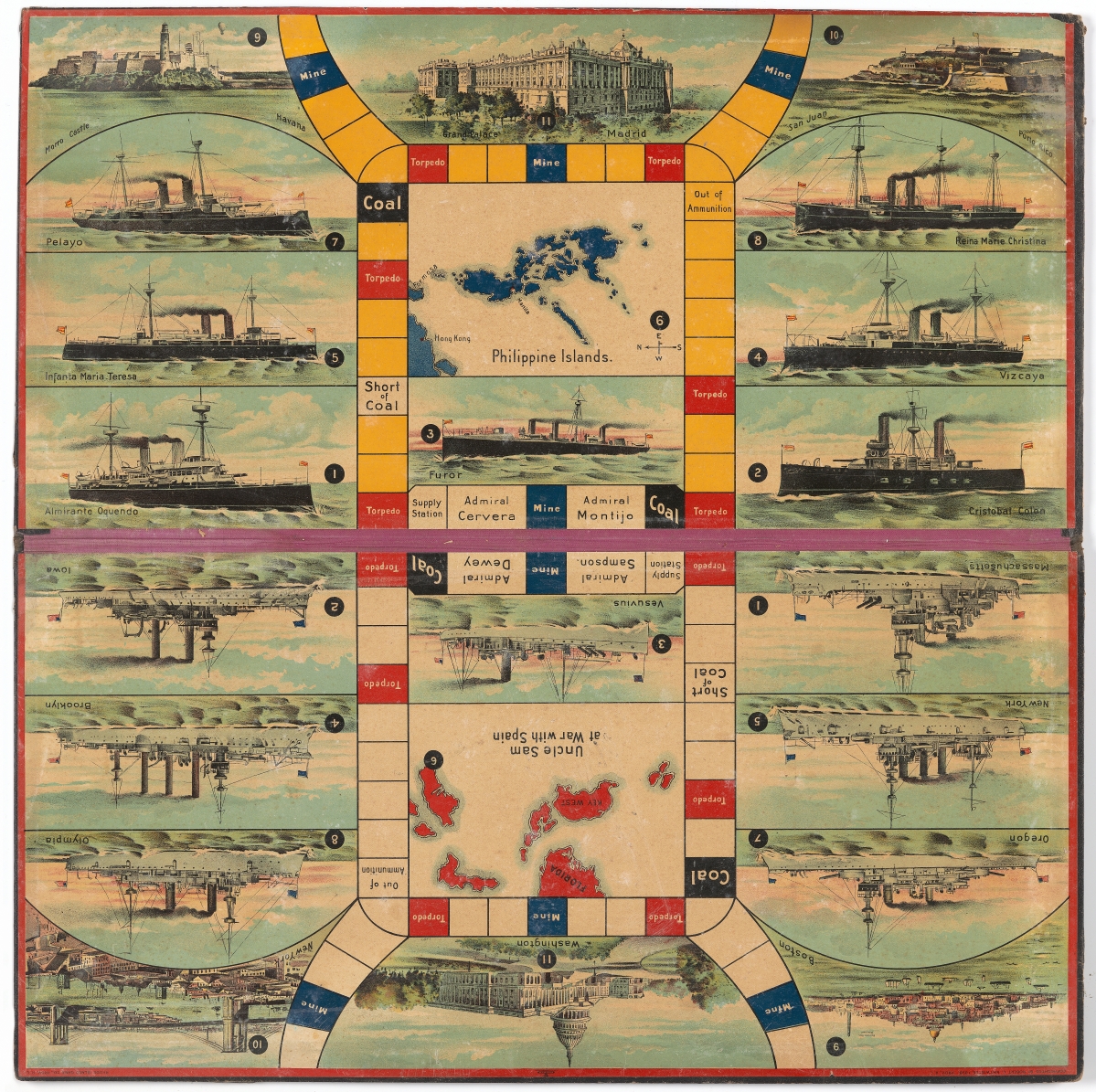

“Uncle Sam at War with Spain,” made by Rhode Island Game Co, 1898, cardboard, metal and printed paper. Collection of Emilio Cueto.

The actions of the United States affected the areas under discussion in different ways, she points out: “The reaction that the Cubans had to occupation, for example, and the establishment of the protectorate was very different than the Puerto Ricans had in 1898 who were optimistic about the change from Spain to the United States. You recognize those differences, but you have to examine critically and not be afraid to look at how much of this was done in less than democratic ways.”

“It was questioned at the time on all those islands and archipelagos that the United States was claiming, and it was questioned even within the United States by intellectuals and politicians who did not adhere to the expansionist views of Theodore Roosevelt or Henry Cabot Lodge, for example. People can take away that 1898 was a moment of public debate, when not everyone was in agreement.”

Kate Clarke Lemay, acting senior historian at the Portrait Gallery, was a perfect co-curator: “I’m interested in military history and how art helps us understand military history. Or helps us remember certain things about warfare and forget other things about war. We were talking about what parts of American history had not been explored, and we realized that we had a show on our hands. And a very interesting show, because it hadn’t been told before from the points of view of these people who became somehow US-affiliated. There was a brief time when all of these archipelagos were part of the US empire, and I don’t think many people know that or understand that history.”

Lemay emphasizes how difficult it is to understand the contradictions of this period.

Detail of Portrait of Queen Lili’uokalani by William F. Cogswell, 1891-92, oil on canvas. Hawai’i State Archives. David Franzen photo.

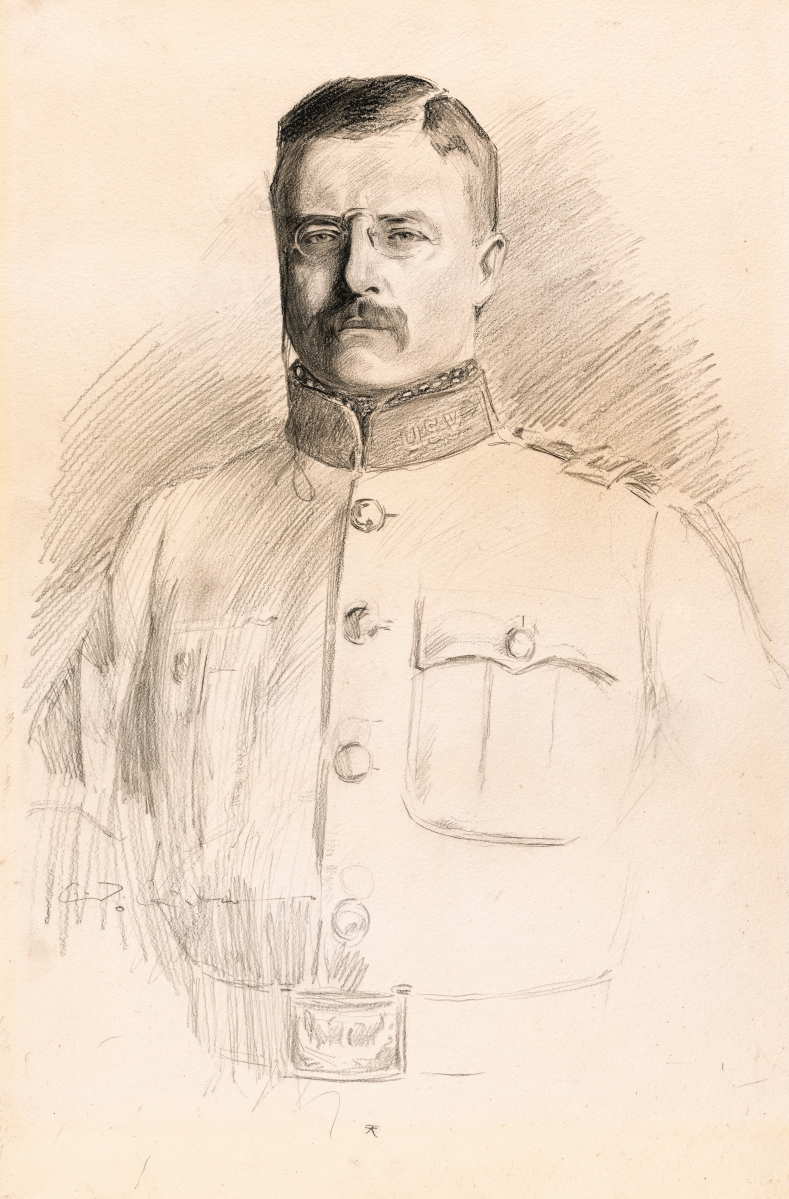

President Theodore Roosevelt is represented in the exhibition by an 1898 portrait drawing in graphite and conte crayon by Charles Dana Gibson (1867-1944), who is best known for his elegant “Gibson girls.” The curator points out, “People admire Theodore Roosevelt for all sorts of things – as an effective politician, who created the National Park system – so progressive in so many ways. But then there was part of his biography dealing with the Spanish-American War, that reveals a very complex man.”

She continues, “It was important to us that people have a more even understanding of history, inclusive of all points of view, not only the dominant view of the era. We look back at history with new eyes and understand it with more nuanced ways. At some point, history becomes dangerous when we view these contours that are difficult for us to come to terms with. I think that the labels we wrote attempt to present all the different points of view for audiences to take into consideration as they come to think about for the first time the Spanish-American War or the war in the Philippines or the Annexation of Hawaii.”

In conclusion, Taina Cargol summed up: “We want this exhibition to be enlightening, to explore things people did not know. Maybe a couple of pages in a history class were dedicated to these episodes, but there should have been a lot more – it’s a very complicated moment. We’d like people to come out with a new understanding of how transformational this moment of history was, not just for the United States, but for all these places that came into their sphere of influence. There were many futures altered right there.”

-1024x816.jpg)

Photographs of the “Committee of Safety” by an unidentified photographer, 1893. Courtesy of the Hawaii State Archives.

The exhibition opens on the 125th anniversary of the 1898 events and will continue through February 25, 2024. Of great interest to historians and art historians will be the accompanying fully illustrated book, 1898: Visual Culture and U.S. Imperialism in the Caribbean and the Pacific, co-published by the institution and the Princeton University Press. Available this summer, the book will include text by the curatorial team and essays by six outside scholars.

In September, the exhibition will be the subject of the biennial Edgar P. Richardson Symposium presented by PORTAL, the Portrait Gallery’s Scholarly Research Center. For a dedicated website and additional events, check www.npg.si.edu/exhibition/1898-us-imperial-visions-and-revisions.

The Smithsonian Institution’s National Portrait Gallery is at Eighth and G Streets. For information, www.npg.si.edu or 202-633-1000.

.jpg)

.jpg)