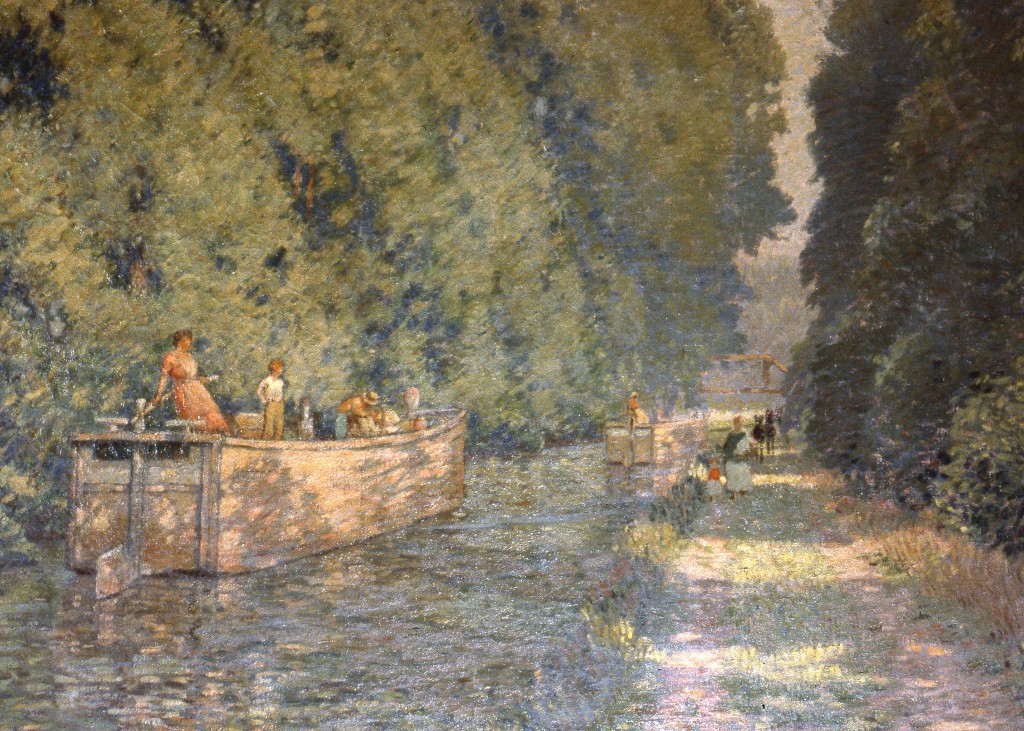

Rae Sloan Bredin first came to New Hope in 1911 to visit a former art school classmate, and likely to study with painter W.L. Lathrop. He returned often to the area before marrying and settling in New Hope permanently in 1914. The Pennsylvania or Delaware Division Canal, a key transportation link built in 1832, was among the landscape features that inspired local Impressionist painters. The attention given to the canal by artists like Bredin and others, as well as its historical importance, helped spur efforts to preserve the waterway in the Twentieth Century. “New Hope Canal” by Rae Sloan Bredin (1880-1933), 1929. Oil on canvas. Gift of Alice P. (Mrs. R. Sloan) Bredin.

By Karla Klein Albertson

DOYLESTOWN, PENN. — The Mercer Museum and Fonthill Castle are operated by the Bucks County Historical Society where, depending on their collecting bent, past visitors may remember the distinctive tiles, the collection of historic tools and stove plates, or the fantastic architecture of the concrete castle. Even the museum website focuses on the objects of everyday life from the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries. But the new exhibition “200 Years of Bucks County Art” will expand that image as it reveals a multiplicity of major fine art works in the institution’s permanent collection.

“Our audiences are often astonished by the extraordinary depth and breadth of the museum’s collections,” stated Cory Amsler, vice president of collections and interpretation, in a preshow press bulletin. “I believe ‘200 Years of Bucks County Art’ will surprise once again as visitors discover the many remarkable paintings, drawings and watercolors featured, and encounter the artists — both prominent and obscure — who produced them.” As the colloquial saying goes, “Who knew?”

In an interview with Antiques and The Arts Weekly, Amsler expanded on the surprise element: “That’s always the first question — what’s the Bucks County Historical Society doing with this collection? The society was founded in 1880 and at that point there really were no other collecting museums or historical organizations in Bucks County. By default, the society would collect objects of cultural heritage and history generally. At that time, the major force in the society was founder William W.H. Davis (1820-1910) — he was very conscious of Bucks County history from the very beginning.” And fortunately for today’s researchers, he considered art as part of that history.

On one wall of the show’s galleries, the role of Davis is explained in depth:

“From the society’s founding in 1880 to his death in 1910, William Watts Hart Davis served as the society’s president and greatest driving force. During his long lifetime, Davis practiced law, fought in the Mexican War, served as District Attorney of New Mexico Territory, published and edited a local newspaper, commanded an infantry regiment in the Civil War, and authored multiple historical volumes. Davis was ever conscious of history, especially when, at times, he was making it.

Jeannetta Beauvais attended the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts between 1948 and 1951. Her subject here, Nelson Derry, worked for several decades in the nursery and greenhouse business owned by the Darlington Family in Doylestown. According to the 1940 census, Derry was still working nearly 60 hours a week at age 77. He died in the Bucks County Home in 1948. “Portrait of Nelson Derry (1864-1948)” by Jeannetta Beauvais (1928-1978), 1947. Watercolor on paper. Gift of the Zecca Family, 2015.

“While serving as the society’s president, Davis accepted or commissioned a number of paintings for the collection. After his death, some works from his own collection entered the society’s holdings. His interest in local and military history, as well as his own personal history, profoundly shaped the Society’s early painting collections. In his view, Bucks County’s artistic heritage was a subset of its broader history.”

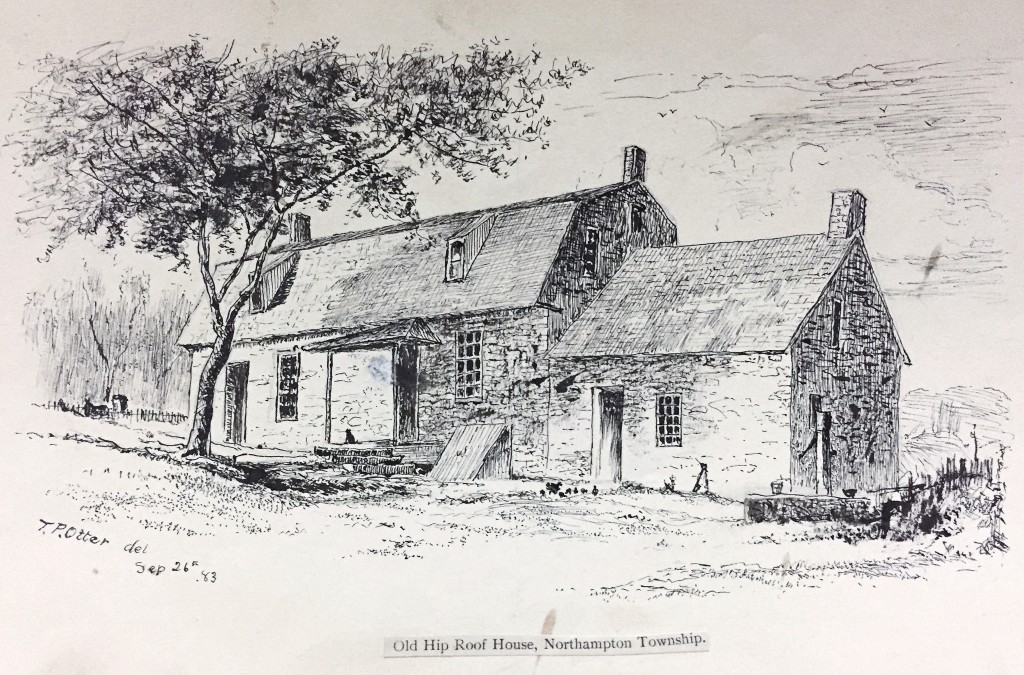

Nearby, viewers can see a photograph of Davis in his office, circa 1905, as well as books written by him, and memorabilia, including his sword and scabbard and the inkwells he used when writing his History of Bucks County, Pennsylvania. Amsler continued, “He had his own art collection, and he had used art from people like Thomas Otter (1832-1890) in his publication on local history. So, between the art Davis collected and the art he was sponsoring and the art that came to the museum because of the historical society, the society collected art right from the get-go.”

“So that was one influence on the society’s art collection and then the other influence was Henry Chapman Mercer (1856-1930) himself. He had been a founding member of the historical society in 1880, but by 1897 he took the society in a much broader direction, beginning to collect not just local material but artifacts, tools and objects of everyday life used in America. A subset of that was art, particularly folk art, although he never used that word. As it turns out, his great-grandfather Abraham Chapman had been an acquaintance of Edward Hicks. So there were a number of works of art, including ones by Hicks, that had come down in his family. Those ultimately came to the museum as part of Mercer’s influence. And Mercer being an artist in his own right, there are works of his in the collection. His interest in collecting focused on what you might call ‘documentary art.’”

For that reason, the exhibition is filled with portraits and landscapes. It makes perfect sense that the two gentlemen who established the organization would be deeply interested in what past residents looked like and where they lived and worked. In the section on Henry Mercer, visitors can see a photograph of him taken around 1925, a copy of his book The Tools of the Nation Maker, published by the Bucks County Historical Society in 1897, which cataloged the first 760 objects he had acquired, and one of the objects — a wrought iron hanging lamp. Then, there are his own pencil, ink and pastel art works, including one of his tile designs and an outdoor view of two men using a pit saw, which showed one of his tools in action.

The exhibition is a must for collectors and art historians interested in the work of Quaker sign painter and folk artist Edward Hicks (1780-1849). Mercer, in his role of cultural archaeologist, unearthed a signboard by Hicks showing George Washington at a Delaware River crossing. The dramatic scene had been adapted from an 1819 painting by Thomas Sully. The full-color sign with its legend below had stood at the Pennsylvania end of a bridge spanning the river. The bridge was washed out in an 1841 flood, but the sign had been salvaged and stored in the attic of an old store. Mercer rediscovered the painting and donated it to the historical society in 1897. In the exhibition, the sign is displayed with two of Hicks most famous compositions — “The Peaceable Kingdom,” where animals and human children stand side-by-side, and “William Penn’s Treaty with the Indians.” He painted many versions of the former and several of the latter, but this “Treaty” copy had descended in the Chapman family.

One of several drawings of historic structures in Bucks County rendered by Otter in the 1880s. The home of a Revolutionary War soldier, the house more properly features a “gambrel” rather than a “hip” roof. “The Old Hip-Roof House, Northampton Township” by Thomas Otter (1832-1890), 1883. Ink on paper. Mercer Library Collection.

Portraits are a major element in the collection, and fortunately the Philadelphia area attracted major artists to fill the demand for representations of family members. Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827) painted the oval images of Richard Gibbs and his wife Margery; Richard Gibbs was the Bucks County sheriff from 1771 to 1773, so the 1975 gift of the pair was a perfect addition to the museum. Peale founded one of America’s first museums in Philadelphia and was the anchor of an extended family of artists.

The portraits — where possible — are bolstered by related artifacts. Thus visitors see not only an 1831 painting of Elizabeth Means Hart of Warminster Township by Robert Street (1786-1825), they also can view her monogrammed silver punch ladle made around 1800 by Samuel Williamson of Philadelphia. Amsler explains, “When we do this kind of exhibition, I want to make sure we include a context for the art work which would include three-dimensional material from our collection to augment the paintings. By adding some of these additional artifacts, it enhances the context of the original art.”

One of the curator’s favorite examples is the material surrounding a portrait of Joseph O.V.S. Archambault (1796-1874) by an unidentified artist. The gentleman had been a member of Napoleon’s staff, came to the states, settled in Newtown, opened a hotel and became local militia officer. On view is the blue militia jacket worn in the portrait, which was given by the family in 1897. The family story continues with paintings of his son Lafayette Archambault and his wife Susan Taylor Archambault.

Amsler next pointed out a 1947 watercolor portrait of Nelson Derry by Jeannetta Beauvais (1928-1978), and said, “For me it’s the stories behind the works that are most interesting.” The text with the painting explains how the African American subject came to Bucks County where he worked for many years in a Doylestown nursery and greenhouse.

Side by side with the portraits, the Nineteenth Century landscapes capture scenes of towns and farms which had vanished by the beginning of the next century. For example, John Mathews (1844-1908) was a tradesman, but, in addition to his “day job,” he had a naïve artistic talent which he used to depict individual farm complexes. He painted the views on display of “The Yost Farm” and “The Chapman Farm” in 1878.

Daniel Garber presented this painting to the Bucks County Historical Society at one of the society’s meetings, held near the artist’s home in Solebury. Although Garber knew nothing of the history of the house featured in his work, a society member informed him that the Quaker poet John Greenleaf Whittier had summered there between 1838 and 1840. During those years Whittier served as editor of the Pennsylvania Freeman, a leading abolitionist newspaper of the day, headquartered in Philadelphia. “October” by Daniel Garber (1880-1958), circa 1918. Oil on canvas. Gift of the artist, 1918.

By the Twentieth Century, Bucks County had become a magnet for artists who wanted to capture the unspoiled scenery of the countryside. At the center of this movement and the “New Hope School” was William Lathrop (1859-1938), who arrived in 1899. One of his paintings in the exhibition shows the historic “Hip Roof House” standing alone in the landscape.

In conclusion, Cory Amsler said, “The bulk of our collection does reference Bucks County; even though Mercer took the museum in a very broad direction, we never stopped being the historical society. Wherever there is a story to be told, that’s where I go. Most of our art holdings are on view in this exhibition, and visitors will be surprised at the strength of the collection and surprised that so much art of national importance is present. To be able to encounter those works here in Doylestown, as opposed to a major art museum in an urban setting, is fairly impressive.”

Although the schedule of exhibition-related events continues to be revised, there will be a series of programs with tours and lectures, although some may be virtual. Mercer Museum is at 84 South Pine Street. For information or hours, www.mercermuseum.org.