Portrait of a female artist with a portfolio (self-portrait?), Anne Gueret, 1793. Katrin Bellinger Collection.

By Z.G. Burnett;

Images Courtesy of The Baltimore Museum of Art

BALTIMORE, MD. — On October 1, the Baltimore Museum of Art (BMA) opened a major exhibition exploring the vast artistic achievements of women artists and artisans from across Europe between the Fifteenth and Eighteenth Centuries. Co-organized with the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO), “Making Her Mark: A History of Women Artists in Europe, 1400-1800” focuses on works that reflect the ways in which women played an integral role in the development of art, culture and commerce across more than 400 years. Acclaimed artists such as Rosalba Carriera, Artemisia Gentileschi, Élizabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun, Judith Leyster, Luisa Roldán and Rachel Ruysch are positioned alongside lesser-known professional and amateur fine artists, as well as talented but often unnamed makers in collectives, workshops and manufactories. While scholarship about historic women artists has seen an increase in recent years, the investigations remain largely focused on an elite group of artists working in large-scale painting and sculpture. “Making Her Mark” explores the breadth of women’s artistic endeavors and innovations through the presentation of more than 175 objects — ranging from royal portraits and devotional sculpture to tapestries, printed books, drawings, clothing and lace, metalwork, ceramics, furniture and other decorative objects — and argues for a reassessment of European art history to incorporate the true depth and variety of their contributions. The exhibition will be on view at the BMA through January 7, and will open in Toronto in March.

“Making Her Mark” is co-curated by Andaleeb Badiee Banta, senior curator and department head of prints, drawings and photographs at the BMA, and Alexa Greist, curator and R. Fraser Elliot chair, prints and drawings at the AGO. The exhibition features several new BMA acquisitions on view for the first time, as well as loans from the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, the National Gallery of Art, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and many other significant public and private collections in North America and Europe. A fully illustrated catalog includes essays and commentary by the curators and other scholars, including Babette Bohn, professor emeritus of art history and women and gender studies, Texas Christian University; Virginia Treanor, associate curator, National Museum of Women in the Arts; and Madeleine Viljoen, curator of prints, New York Public Library.

Self-portrait by Sarah Biffin, circa 1842. The Baltimore Museum of Art, Rhoda M. Oakley Prints, Drawings & Photographs Acquisition Fund, Contemporary Deaccessions Endowment, The John Dorsey and Robert W. Armacost Acquisitions Endowment.

“My co-curator and I wanted to organize an exhibition that examined pre-modern European art through a lens that would resonate with contemporary audiences,” said Banta. “The narrative of women artists of the past being rare or comparatively less talented than their male counterparts was one we had been taught for decades and it felt increasingly hollow and unexamined. So, we decided to make an exhibition entirely devoted to women makers to see what has been missing from the established story of Western art history.”

“We are delighted to present this groundbreaking exhibition that will bring together exceptional works of art, craft, and design by women artists from a period and a field that has largely equated talent and artistic excellence with men, and painting and sculpture,” said Asma Naeem, the BMA’s Dorothy Wagner Wallis director. “The exhibition explores women’s essential work in the development of new ideas, aesthetics, creative movements and commerce of the time. By recontextualizing this period in history and offering these women artists the attention they deserve, we hope to inspire our community to reimagine what they have previously held to be true about both art and history, and to contribute to the critical work of rectifying centuries of omissions.”

For centuries, women who achieved professional artistic careers were deemed anomalous or exceptional, while those who engaged in creative pursuits in the home were dismissed as amateurs. “Making Her Mark” aims to correct these commonly held beliefs by examining the different ways in which women contributed to the evolution of art and to the proliferation of cultural trends and commercial successes. Their roles as artists, designers, laborers and business professionals are given life through a variety of objects and through narratives seldom, if ever, told. In this way, the exhibition not only expands our understanding of women’s contributions but of art history more broadly, encompassing making well beyond the established dominance of painting and sculpture.

Paper filigree cabinet on stand with hairwork and watercolor panels, Sophia Jane Maria Bonnell and Mary Anne Harvey Bonnell, circa 1789. Pelling Place, Berkshire. The Baltimore Museum of Art: Decorative Arts Acquisitions Endowment established by the Friends of the American Wing.

“Although this is not the first exhibition to focus on women artists of Europe before 1900, it is the first of its kind to pursue such an expansive scope in terms of geography, chronology and most importantly, media,” Banta continued. “Expanding beyond the traditional focus on painting and large-scale sculpture — categories historically deemed important by men — allowed us to see more clearly the types of works that women actually made and broaden our consideration of the lesser-recognized ways that women were engaged with the process of making art in a variety of media.”

This institutional preference for large-scale artwork is a continuation of female suppression in the arts, which has been in practice since the beginning of the academic studio system, a perpetuation that Banta aims to correct with “Making Her Mark.” “Due to historical circumstances, women generally did not have access to the same training and resources as their male counterparts and therefore pursued artistic expression through different materials and ways of making that were typically more collaborative and produced smaller or utilitarian objects fashioned from more fragile materials,” she explained. “These qualities have resulted in many of these objects being relegated to the category of ‘material culture’ rather than ‘fine art’ and thus not given the same amount of attention or display priority in standard museum practices.”

Banta also shared ideas for other institutions seeking to make the artwork by its anonymous female makers more visible. “This project has taught us that open-minded research is key to identifying the potential for a woman’s involvement in the production of a work of art. Rather than approach a work assuming that a woman was not involved, instead we considered the ways that a woman may have been integral to its realization even if her name is not associated with it,” she said. “Labels of ‘anonymous’ or ‘unidentified’ leave open the door for possibility. We have also found that much of what women made was not easily categorized into established departmental media divisions in museum collections. Collaborating and consulting with curators and conservators across media was an essential part of identifying where women’s historical creativity may lie.”

“Shock Dog” (nickname for a dog of the Maltese breed), Anne Seymour Damer, circa 1782. The Metropolitan Museum of Art: Purchase, Barbara Walters Gift, in honor of Cha Cha, 2014.

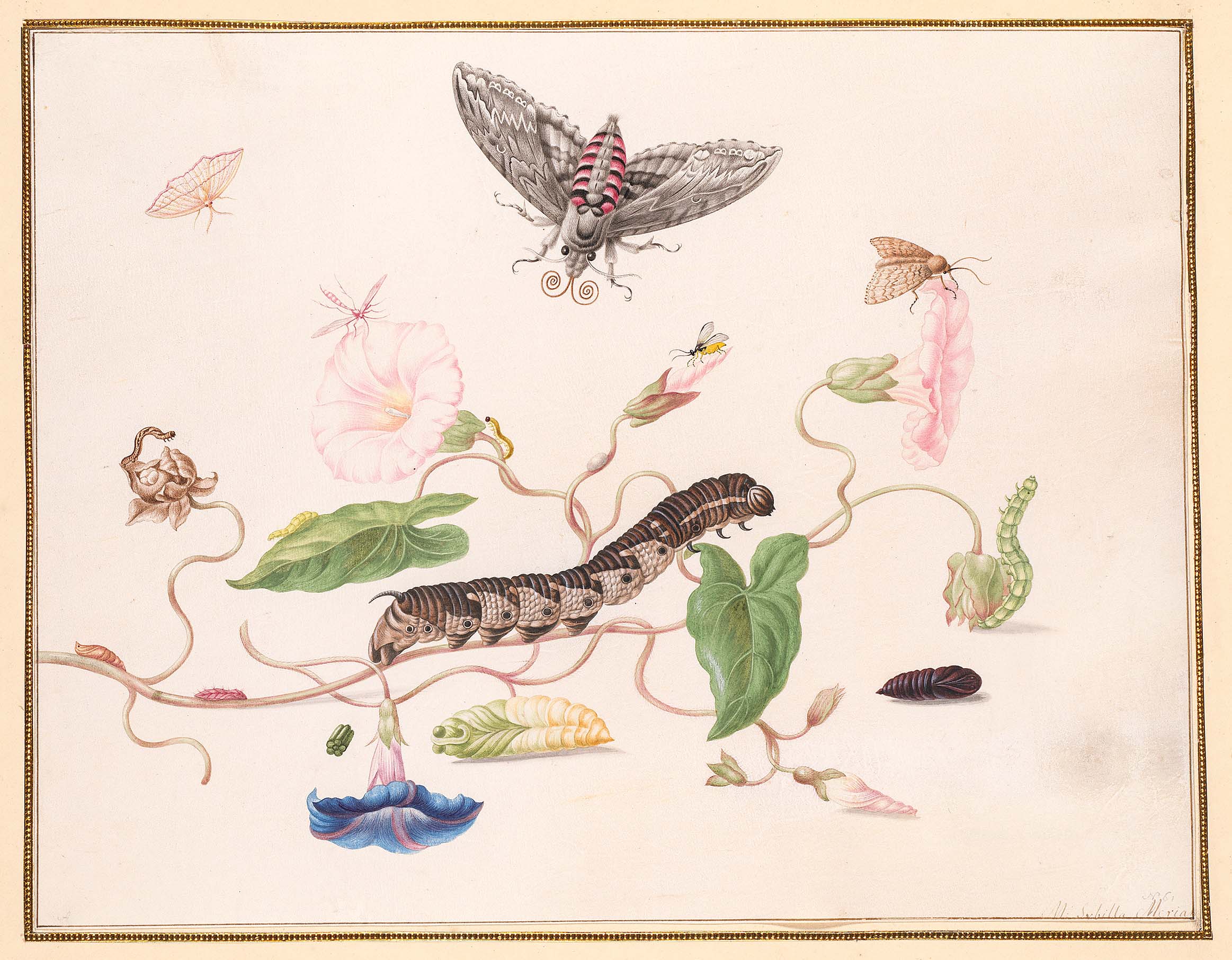

The exhibition is organized in four distinct sections: “Faith & Power” examines patronage of women artists by the ruling classes as well as objects made in convents and within other religious communities for ceremonial purposes. Examples include Luisa Roldán’s terracotta “Education of the Virgin” (1689-1706), Artemisia Gentileschi’s painting “Judith and Her Maidservant with the Head of Holofernes” (circa 1623-25) and illuminated manuscripts, reliquaries and lace made by cloistered women across Europe. “Interiority” explores the personal worlds of domestic labor, interior decoration and the private arts of calligraphy, drawing and embroidery. Beautiful still life paintings by Anne Vallayer-Coster and Josefa de Ayala and an Eighteenth Century wooden cabinet with paper filigree and hairwork panels by Mary Anne Harvey Bonnell are among the highlights. “The Scientific Impulse” showcases both professional and amateur naturalist drawings and paintings of flora and fauna with examples by Pauline Rifer de Courcelles (Madame Knip), Giovanna Garzoni, Maria Sibylla Merian, Rachel Ruysch and many others. In particular, it demonstrates women artists’ involvement in the documentation of natural phenomena brought to Europe through the extractive trade of empire and also explores women’s involvement in the medical and astronomical sciences. “The Entrepreneurial Spirit” uncovers women’s roles in the businesses of arts production, promotion and education. Highlights include self-portraits by Sarah Biffin and Judith Leyster, an elaborate porcelain tea service by Marie-Victorie Jaquotot, textiles by Anna Maria Garthwaite and an exquisite marble sculpture of a Maltese dog by Anne Seymour Damer.

“The presence of women as makers remains largely anomalous or anonymized in the halls displaying pre-modern art of European and North American museums. Their absence speaks to the biases inherent to the study of women’s artistic output as well as to the ongoing gendered notions of the heroic and spectacular as the standard measure of quality, significance and legitimacy in Western culture,” said Banta. “‘Making Her Mark’ challenges these criteria and promotes the depth and range of women’s innovation and acumen within the creation of art and the growth of the art business, working to establish a new, more expansive and inclusive art history that speaks to these achievements.”

The Baltimore Museum of Art is located on the Johns Hopkins University campus at 10 Art Museum Drive. For information, www.artbma.org or 443-573-1700.