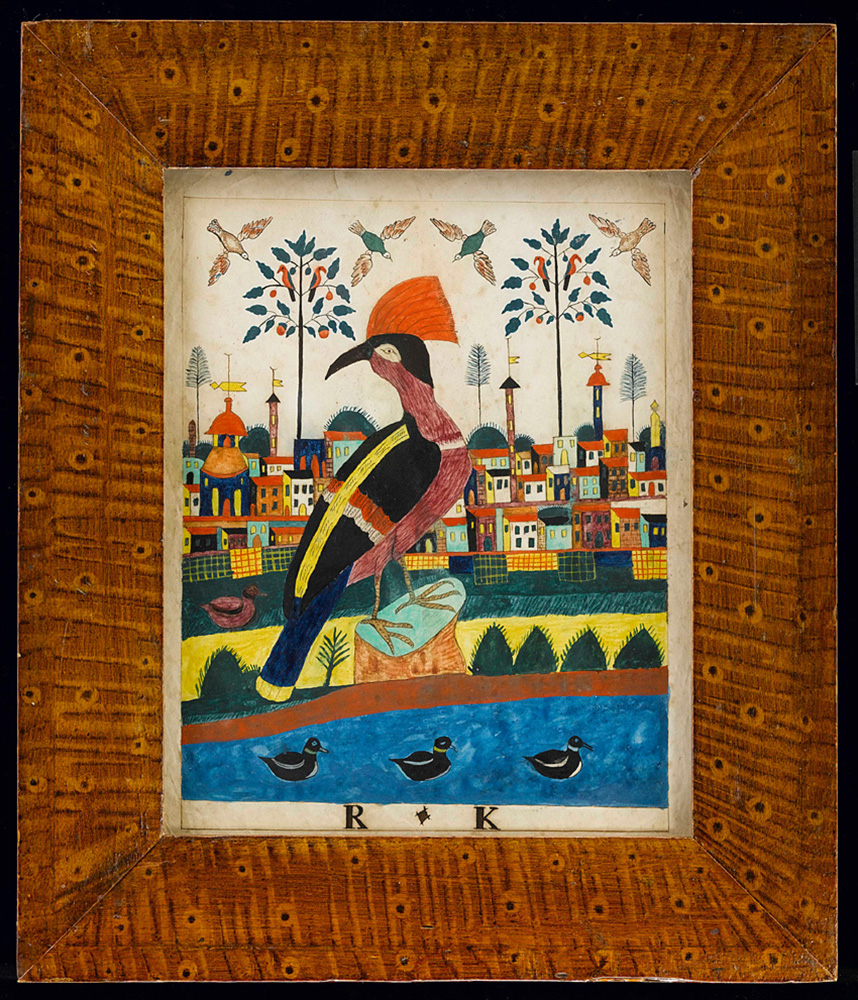

Attributed to Abraham Heebner (1802–1877), “Exotic Bird and Townscape,” Montgomery County, Penn., circa 1830–1835, watercolor and ink on paper, 8¾ by 6 inches, collection of Jane and Gerald Katcher, ex Edith Halpert. Hundreds of folk art paintings and sculptures passed through Halpert’s gallery during her long career as a dealer. She kept a select number for herself, three of which are in this exhibition.

NEW YORK CITY — American Modernist artists, together with a group of collectors, dealers, curators and scholars whose pioneering interest in traditional folk art gave rise to a disciplined branch of study within the continuum of art history, will be the focus of an exhibition opening at the American Folk Art Museum July 18, and on view through September 27.

Organized by the Fenimore Art Museum in Cooperstown, N.Y., “Folk Art and American Modernism” will shed light on how portraits and paintings, carvings, painted furnishings, hooked rugs and even duck decoys, all made by America’s earliest self-taught artists, influenced American Modernist art in the 1920s and 30s, at the same time fostering a new field of discourse in art, and creating a new market.

More than 80 works will be on view, organized in groupings around such early Twentieth Century figures as Hamilton Easter Field and Robert Laurent, William and Marguerite Zorach, Juliana Force, Charles Sheeler, Elie and Viola Nadelman, Isabel Carleton Wilde, Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, Holger Cahill, Edith Gregor Halpert, Jean and Howard Lipman, and others.

“American Interior: Ridgefield, Connecticut” by Charles Sheeler (1883–1965), 1934, oil on canvas, 32½ by 30 inches, Yale University Art Gallery, gift of Mrs Paul Moore. This work is the last of Sheeler’s “American Interiors” series, rendered in his precisionist style. He painted it from a photograph made in 1929, before he moved from the South Salem, N.Y., cottage and after his wife, Katharine, had died.

“It is remarkable to see and understand why early American works made by self-taught artists remain bold statements of independence to this day,” said Dr Anne-Imelda Radice, executive director of the American Folk Art Museum. “Were it not for those spotlighted in this exhibition, the field of study that we know as folk art, and the works of art we so treasure, would probably not exist.”

Andy Warhol (1928–1987), an avid folk art collector, called the work of early decorative painters in the US “America’s first abstract expressionism” while French-born, American sculptor Robert Laurent (1890–1970) was fascinated by the carved wings of a duck decoy made by an anonymous self-taught artist. Sculptor Elie Nadelman (1882–1946) found in early American folk art the pure lines and abstracted, streamlined forms that informed his work.

Attributed to the Wilkinson Limner (active 1824–1830), “Young Woman with Elaborate Lace Collar and Holding a Red Book,” probably Philadelphia, circa 1827, oil on cradled poplar panel, 27½ by 21¼ inches, collection of Eric J. Maffei, ex Juliana Force. Part of a pair, the location of the man’s portrait is presently unknown.

Interest in folk art by Laurent, Nadelman and a handful of other artists in the early Twentieth Century gave rise to the first documented, public discourse in this area of art history, along with attention from curators who recognized its aesthetic power, scholars who understood its historic importance, individuals who sought to build important collections of this unconventional American art and dealers who recognized its value.

“Folk Art and American Modernism” is organized around these first connoisseurs of early American folk art, in groupings that highlight the paintings, sculpture and aesthetic objects made by Modernist artists who were inspired by this art by the self-taught; and in groupings of works that were collected those who recognized its historic and aesthetic value. The exhibition documents how their collective nascent interest grew into today’s established museums and prestigious repositories for study and exhibition of early American folk art.

John Haley Bellamy (1836–1914) eagle with flag, Maine, 1890, paint on carved wood, 8 by 27 by 4 inches. Newark Museum; bequest of Dorothy Canning Miller Cahill, ex Holger Cahill. Bellamy was born in Kittery Point, Maine, and as a young man trained with the Boston carver Laban Beecher. Cahill found this Bellamy eagle in 1938 in a Boston shop owned by Fred Finnerty.

Antiquarians and ethnologists of the late Nineteenth Century were interested in American folk art, but it was not until the 1910s, when American Modernist artists and art critics began to celebrate unpretentious, locally made objects for their formal artistic qualities that these “folk” works were recognized as art. The objects included furniture and decorative works; portraits made in the years before photography became widespread; duck decoys and trade carvings; weathervanes, whirligigs and toys; textiles; and other works made throughout the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries by members of diverse immigrant groups, many of whom brought with them and maintained traditions from their respective cultures.

Curators, collectors and artists who shared this interest in folk art accumulated such material as inexpensive furnishings, and viewed them as a rebellion against the strictures of the established art academy. The artists saw connections between American folk art and the powerful visual movement they had observed and studied in Europe — Modernism, marked by bold use of color, flattened and streamlined forms and other attributes. In regarding their folk objects as art — and as art that shared characteristics with their own work — these artists were seeking to document a continuous American artistic tradition of which they could consider themselves a living part.

The American Folk Art Museum is at 2 Lincoln Square. For information, 212-595-9533 or www.folkartmuseum.org.

Read article and see more images inside July 10, 2015 E-edition