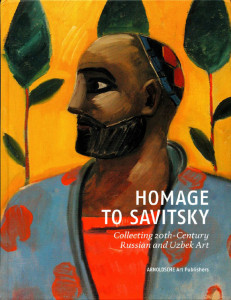

Homage to Savitsky: Collecting 20th Century Russian and Uzbek Art; Ildar Galeyev, author, Russian edition; English edition by Friends of the Nukus Museum (editor); Arnoldsche Art Publishers, Stuttgart; www.arnoldsche.com; 2015; hardcover; 216 pages; $70.

In the city of Nukus, set in the desert of northwest Uzbekistan, the passionate art collector Igor Vitalievich Savitsky (1915–1984), felt the “flame of conscience” and began to assemble a vast treasure of artwork. Besides a wide range of Karakalpak folk art and archaeological finds from the ancient civilization of Khorezm, the Karakalpakstan State Museum of Art (KSMA), which Savitsky founded in the mid-1950s, houses the second largest collection of Russian and Uzbek avant-garde art in the world (after the Russian Museum in St Petersburg).

Unnoticed by the international art world until recently, this extraordinary museum is the life work of Savitsky, a Russian painter born in Kiev, who first visited Karakalpakstan in 1950 as a member of the famous Khorezm Archeological and Ethnographic Expedition led by Sergei Tolstov.

To celebrate Savitsky’s 100th birthday, Homage to Savitsky presents selected works from the museum’s holdings and from private collections in Moscow, shedding new light not only on the achievements of this remarkable personality but also on some of the artists whose legacy he preserved. With chapters devoted to Savitsky’s letters, articles and other documents; a chapter on recollections on Savitsky and a biographical essay on the slim, not very healthy and yet devoted collector; a remembrance and a final chapter on understanding Savitsky, this book helps make the Savitsky Collection in the KSMA accessible to a broad international audience for the first time.

Having moved from Moscow to Nukus, Savitsky began collecting the works of the Russian avant-garde — including of such well-known names as Falk, Mukhina, Koudriachov, Popova and Redko — whose paintings were banned during Stalin’s rule and through the 1960s because they did not conform to the officially prescribed Soviet “socialist realism” school of art. Although a fine artist in his own right, Savitsky stopped painting and dedicated his life to forming a remarkable collection.

How he overcame official dictates and lack of funds to collect the folk art and fine art now contained in the museum is difficult to understand. His biographers and friends describe him as having a “flame of conscience,” a term Maximillan Voloshin coined. “Savitsky’s decision to give up his own art and dedicate his life the art of others was not a victory for the art collector over the artist, it was the flame of conscience,” according to Irina Korovay who traveled with Savitsky to Nukus.

During his relatively short life — he died in Moscow in 1984 — Savitsky was able to collect, catalog and hang this collection, which may now be viewed and appreciated in Homage to Savitsky.

In 2011 at the Galeyev Gallery in Moscow, an exhibition of the same name was accompanied by a catalog, which was the foundation of this book. Ildar Galeyev, the book’s creator, agreed to an English edition when the Friends of the Nukus Museum and the Karakalpakstan State Museum of Art proposed it. The resulting volume incorporates all the photographs from the catalog as well as many others of the KSMA collection. The additional essays and appendices round out the volume to create a book that advances our understanding and appreciation of this unique collection.

The volume is strongly recommended to all who are interested in avant-garde Russian art, early Uzbek art and folk art and the history of an extraordinary collector, I.V. Savitsky.