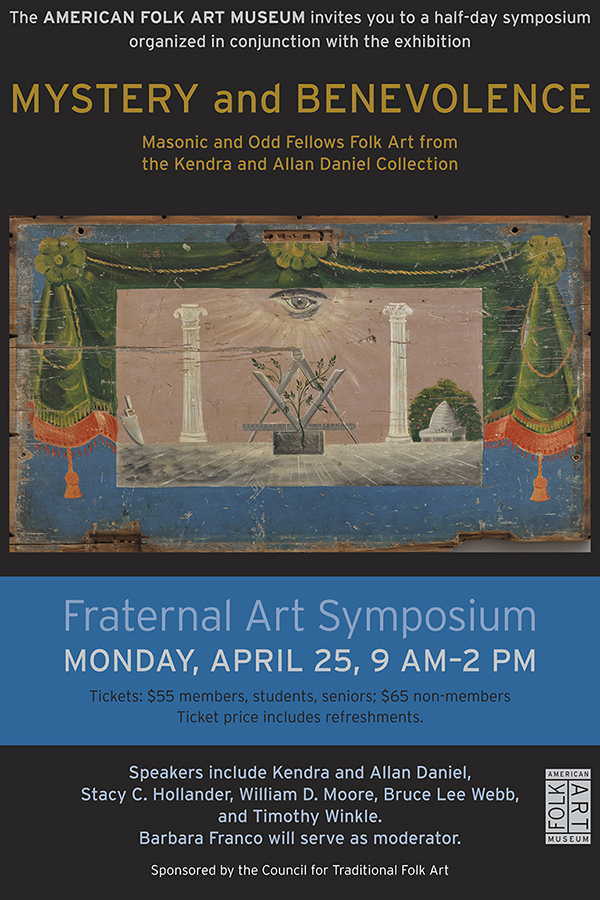

NEW YORK CITY — Enlightenment, wisdom, friendship, charity and trust are but a few of the ideals made manifest through works of art in “Mystery and Benevolence: Masonic and Odd Fellows Folk Art from the Kendra and Allan Daniel Collection,” the first exhibition to document the rich aesthetic heritage of cultural artifacts related to fraternal orders in the United States.

Independent Order of Odd Fellows inner guard robe, the Ward-Stilson Company, New London, Ohio, 1875–1925, velvet, cotton and metal, 37 by 23 inches.

On view at the American Folk Art Museum through May 8, the more than 200 works — ritual props, embellished architectural elements, lodge furnishings, hand stitched and painted banners and aprons — were made by self-taught artists, artisans and manufactories from the late 1700s through the early decades of the Twentieth Century for secret societies that flourished in plain sight throughout America. The exhibition celebrates and commemorates a major gift from Kendra and Allan Daniel, a museum trustee, who assembled the collection over the course of 30 years.

Stacy C. Hollander, deputy director for curatorial affairs and chief curator at the American Folk Art Museum, organized the exhibition with Aimee E. Newell, PhD, director of collections at the Scottish Rite Masonic Museum & Library, a guest curator.

Independent Order of Odd Fellows apron, artist unidentified, United States, 1840–60, paint, gold paint and ink on silk satin, with cotton fringe and bullion trim, 16 by 17½ inches.

Freemasons, Odd Fellows and other fraternal organizations rooted in fellowship comprise one of the largest social and benevolent movements in early American history. In 1900, virtually one in every five men belonged to a fraternal society. Such organizations continue to bring members together to share values, improve themselves and their communities and help others, particularly those in need. Each order conveys messages and honors their collective brother- and sisterhoods through ceremonies, rituals and moral teachings, which are rooted in symbolic systems that impart and reinforce core tenets among their constituents.

On view in the exhibition are imposing architectural elements (carved columns, archways and a dramatic painted scenic backdrop); ritual and ceremonial objects (tracing boards replete with symbols used as mnemonic devices, handcarved staffs, banners); personal items (aprons, certificates and medals); lodge furnishings (altars and three-dimensional symbolic props). All are imbued with an amalgam of time-honored hieroglyphs that members recognize and revere for their encoded meanings.

These symbols, often exuberantly rendered with meticulous care in a variety of mediums, include: square and compasses, all-seeing eyes, hands, stars, arrows, skulls and crossbones and many more. While each fraternal group has different regalia and ritual stories, they share the use of a symbolic language and employ the icons to teach similar virtues.

Freemasonry is the earliest fraternal order in America, introduced in the 1720s. Its ideals were closely allied with enlightenment thought, and many of America’s founding leaders — including George Washington — were Masons. The early national period witnessed the incorporation of Masonic symbols into virtually every aspect of everyday life, from ceramic wares to decorative arts to textiles.

Chest lid with Masonic painting, artist unidentified, probably New England, 1825–45, paint on pine, 22¼ by 37¼ by 25⁄8 inches.

Odd Fellowship was officially instituted in Baltimore in 1819 and became one of the largest fraternities in the United States. Beginning in the 1820s a movement against Freemasonry gained traction and ultimately became a political party, but this backlash saw a decline under the presidency of Andrew Jackson, who was himself a Mason. Following the Civil War there was once again a widespread drive for the comradeship and unity offered by fraternal societies.

Prior to the Civil War, many objects associated with fraternal practice were made by the same artisans who were plying decorative trades in the early years of the nation. The economic potential of fraternal orders was widely recognized and numerous artists made the accouterments and props needed for lodge meetings. They specifically incorporated fraternal symbols within their works to appeal to this market.

In the years following the Civil War, and with the resurgence of fraternal participation, these paraphernalia, once made by hand or produced in small workshops, were increasingly made in larger manufactories devoted to the fraternal trade. Handwork continued to be associated with embroidered uniforms and banners, but many of the artifacts were now made by machine.

Independent Order of Odd Fellows tracing board, artist unidentified, United States, 1850–1900, oil on canvas, 33¼ by 39½ by 21⁄8inches (framed).

The material culture of fraternity comprises a large and important area of American art. Following a pattern similar to other arenas of self-taught or folk art before the age of mass production, the artist who painted a portrait or piece of furniture might also decorate a parade banner, an apron, symbols on a chart or a backdrop for a lodge. Techniques and motifs associated with folk art traditions are found in the art of fraternal orders, and this visual language persists and continues to resonate today.

Highlights of the exhibition include an early daguerreotype portraying an Odd Fellows member wearing his collar and apron. The symbols clearly visible on the heavily fringed apron show a tent and crossed shepherd’s crooks, among others, indicating that the unidentified gentleman had received the Odd Fellows Encampment degree. This was conferred on members only after they had achieved prior degrees.

“Washington as a Freemason,” publisher unidentified, United States, late Nineteenth Century, oleograph on linen, 28½ by 223⁄8 by 13⁄8 inches (framed).

Carpenter James J. Crozier’s (1867–1950) exquisite tilt top marquetry table, the center of which features a shield prominently marked “I O O F” and “F L T,” with heart in hand, all-seeing eye and three-link chain symbols, is on view. With these initials and symbols, Crozier identified himself as a member of the Independent Order of Odd Fellows, a fraternal group that originated in England in the 1700s and arrived in the United States by 1819.

The three-link chain with initials standing for “Friendship, Love and Truth” reminded members of their ritual teachings from the initiatory degree: like the chain, they were bound together in those virtues. The all-seeing eye symbolized the omniscience of God, and the heart in hand signified candor and sincerity.

Two quilts are included, one boldly appliquéd with the repeated motif of the Odd Fellows links, the other a magnificent album quilt with the symbols of Freemasonry filling each block.

There is a varied collection of staffs and rods, one of which, particularly unique, is known as “Aaron’s Budded Rod,” a red pole that curves at the top, has five “buds” that extend to the sides and is topped by a crown-shaped finial. When the Odd Fellows followed a five-degree structure, the rod was part of the Fifth, or Scarlet Degree, and it was recognized as an “emblem of life-giving truth.”

A stunning sign from an Odd Fellows lodge, red with gold letters, reads “Bury the Dead.”

The American Folk Art Museum is at 2 Lincoln Square. For information, 212-595-9533 or www.folkartmuseum.org.