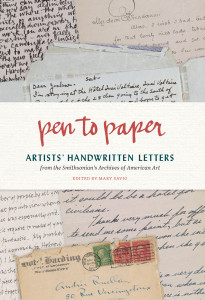

We email, we text, we update our status, we tweet, but it is the rare person these days who actually puts pen to paper. It was not always this way, as Pen to Paper, a collection of letters by artists from the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art, reveals. Edited by Mary Savig, curator of manuscripts at the Smithsonian, this just-published book explores what we can learn from the handwriting of celebrated artists such as Mary Cassatt, Frederic Church, Howard Finster, Winslow Homer and others.

What is the mission of the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art?

Since its founding in 1954, the mission of the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art has been to collect, preserve and make available the primary materials documenting the history of the visual arts in the United States. With more than 20 million items in our continually growing collections, we are the keepers of the backstories contained in letters, diaries, sketchbooks, photographs, financial records, digital media and oral histories of generations of artists, dealers, critics and collectors.

What was the genesis of this book?

One of my colleagues recognized the bold calligraphic handwriting of Ad Reinhardt from across a room! This prompted a conversation about recognizable handwriting in our collections. We quickly realized that our discussion intersected with national debates about the continued relevance of handwriting in American culture. In this era of digital communication, we’re eager to make handwritten documents more accessible online and also to celebrate the inimitable, personal qualities of the handwritten record.

Pen to Paper: Artists’ Handwritten Letters from the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art, published by Princeton Architectural Press, 2016.

What is it about handwriting that allows the reader to detect mood or some insight about the person behind the pen?

The fluidity of handwriting opens it up to interpretation and analysis. When someone spends a lot of time with an artist’s handwritten texts, one learns the minor inflections that express a certain mood or moment in time. In 1921, photographer Berenice Abbott wrote to sculptor John Storrs about her fascination with Berlin. She gushes about Berlin’s art, culture and even the city’s “dry-cold-fresh” air. According to art historian Terri Weissman, “the feeling of speed, the flow of her cursive, the manner in which she writes against the grain and crowds the edge of the page — these qualities communicate Abbott’s exuberance and certainty of observation, as well as her commitment to an artist’s life.”

Penmanship used to be an important signifier of one’s taste and sophistication. Can you trace the arc of when copybook methods gave way to unique handwriting?

Writers have always disrupted penmanship conventions. Handwriting tutorials and copybooks provide the fundamentals, but somewhere along the way, we develop our own personal style. Many artists are more self-conscious about this and therefore treat handwriting as an extension of their creative practice.

When it comes to an artist, we naturally want to compare their handwriting with their work. An example of an artist’s “performative” writing?

Lenore Tawney was a celebrated fiber artist. She also mailed beautiful collage postcards for her friends and acquaintances. Her intricate script is comparable to needlework — each stroke of her pen is delicate. As Kathleen Nugent Mangan points out in the book, Tawney suggested a parallel between a line of text and a line of thread in her diary: “Words and letters can be compacted to a dense knot or drawn out to great length … They could be plaited [or] twisted.”

How many examples do you cover in your book?

There are 56 essays in the book, each contemplating the handwriting of an artist. The essayists include curators, professors, graduate students, archivists and artists. In the introduction, I consider various qualities of 16 letters to situate the various ways of approaching handwriting in manuscript collections.

To purchase a copy of Pen To Paper, click here.

—W.A. Demers