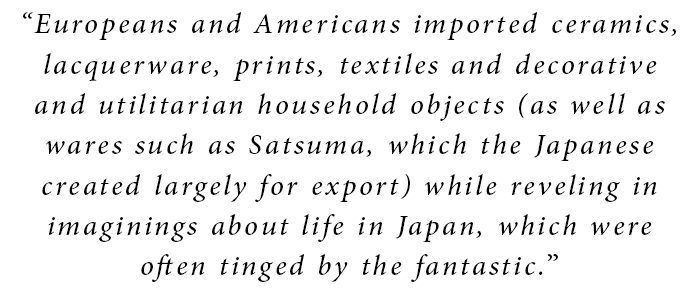

Henry Walters purchased this vase at the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco. Vase with dragon by Kato Tomotaro (Japanese, 1851–1916), circa 1915. Porcelain with underglaze blue and overglaze enamels, 13-9/16 inches. Collection of the Walters Art Museum, Baltimore. —Susan Tobin photo

By Kate Eagen Johnson

SACRAMENTO, CALIF. – “The cross-pollination is just so rich.” Scott A. Shields, PhD, the associate director and chief curator of the Crocker Art Museum, aptly turned to nature to characterize the interplay between Japanese and American art and design. “This is equally true of the art produced in California, which has a long history of influence from Asia.”

He made these observations while discussing “JapanAmerica: Points of Contact, 1876-1970,” on view at the museum February 12-May 21. The traveling exhibition was organized by Nancy E. Green, the Herbert F. Johnson Museum’s Gale and Ira Drukier curator of European and American art, prints and drawings, 1800-1945.

“JapanAmerica” first appeared at Cornell University’s Johnson Museum in 2016.

Shields, who serves as the show’s in-house curator, underscored how the exhibition with its nearly 200 objects “is one of the largest that the Crocker has ever mounted.” He continued, “Though visitors familiar with the evolution of American art may already recognize the effect of Japanese art on American design and painting in the late Nineteenth Century, they may not be aware of the extent and endurance of this influence, which continued well into the Twentieth Century, in large part because of international expositions. The exhibition also makes clear that the influence was reciprocal, and that Japanese artists were also deeply impacted by Western aesthetics and tastes.”

A companion catalog, edited by Green and Christopher Reed, contains essays by seven scholars. Some essayists focused on the range of Japanese arts and Japanese-inspired art objects displayed at international expositions, while others analyzed Japanese and American artistic interchange beyond world’s fairs, including the conduit provided by First Japan Manufacturing and Trading Company, Yamanaka & Co., Morimura Brothers, Vantine’s and other export and import businesses.

Green explained, “The ‘craze’ for Japan varied in its implementation, from citation of Japanese motifs to more fundamental applications of Japanese compositional techniques in the work of American artists and designers, even as Japan positioned itself internationally in competitive emulation of the West, self-consciously producing its own versions of Modern art, design and folk culture. Today, people forget how important the fairs were to the understanding of other cultures and how visitors often came away with new ideas about everything, from technology to design to engineering and artistic influences.”

During the second half of the Nineteenth Century, the mystery and romantic allure of Japan had been heightened by centuries of inaccessibility. In the 1630s, the shogun Tokugawa Iemitsu fully established limitations on foreign travel and commerce, fearing that political destabilization would result if greater numbers of Japanese converted to Christianity and if feudal lords established individual trading relationships with Western merchants. Over the years, the Tokugawa shogunate continued to restrict contact with the West just as adventurous Europeans and Americans continued to attempt entry. When American Commodore Matthew Perry and his warships forcibly sailed into Edo (Tokyo) Bay in 1853, the proverbial writing was on the wall. Soon after, Japanese representatives signed trade agreements with various nations, including the United States in 1854.

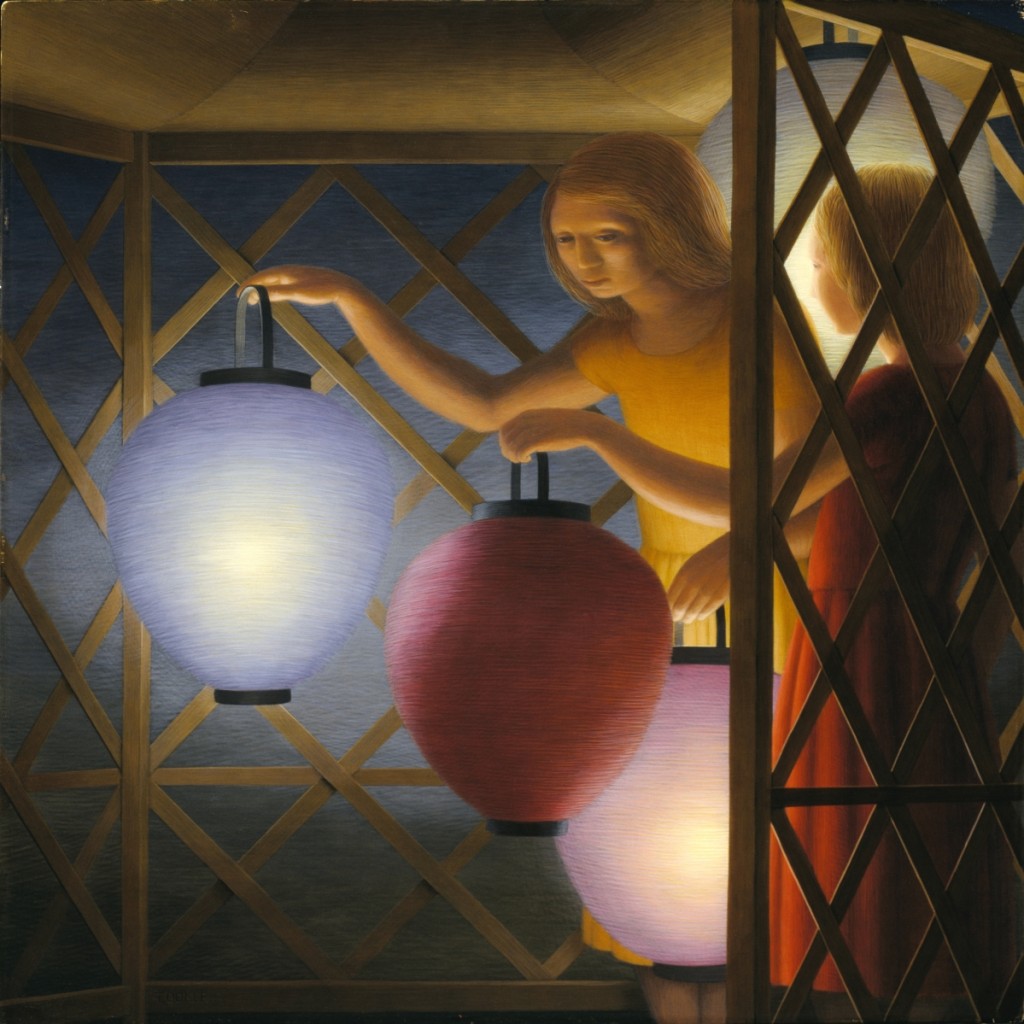

Thus, the fascination with all things Japanese took off, one of many exotic tastes trending during the Victorian era. Europeans and Americans imported ceramics, lacquerware, prints, textiles and decorative and utilitarian household objects (as well as wares such as Satsuma, which the Japanese created largely for export) while reveling in imaginings about life in Japan, which were often tinged by the fantastic.

Two decades after its “reopening,” Japan joined in Philadelphia’s 1876 Centennial Exposition. Americans stared in wonder as Japanese craftsmen erected the commissioner’s residence, the first traditional Japanese building constructed in America, and the Japanese Bazaar. They were likewise mesmerized by the objets d’art on display, all of which were for sale. Not leaving retail opportunities to chance, the Japanese showed items they believed would appeal to Western consumers. Green elaborated, “In America, the Centennial was the place where many … first saw Japanese art and what they saw wasn’t ukiyo-e woodcuts – none were exhibited – but the beautifully crafted metalwork, ceramics, scroll paintings, cloisonné and lacquerware that was on display.”

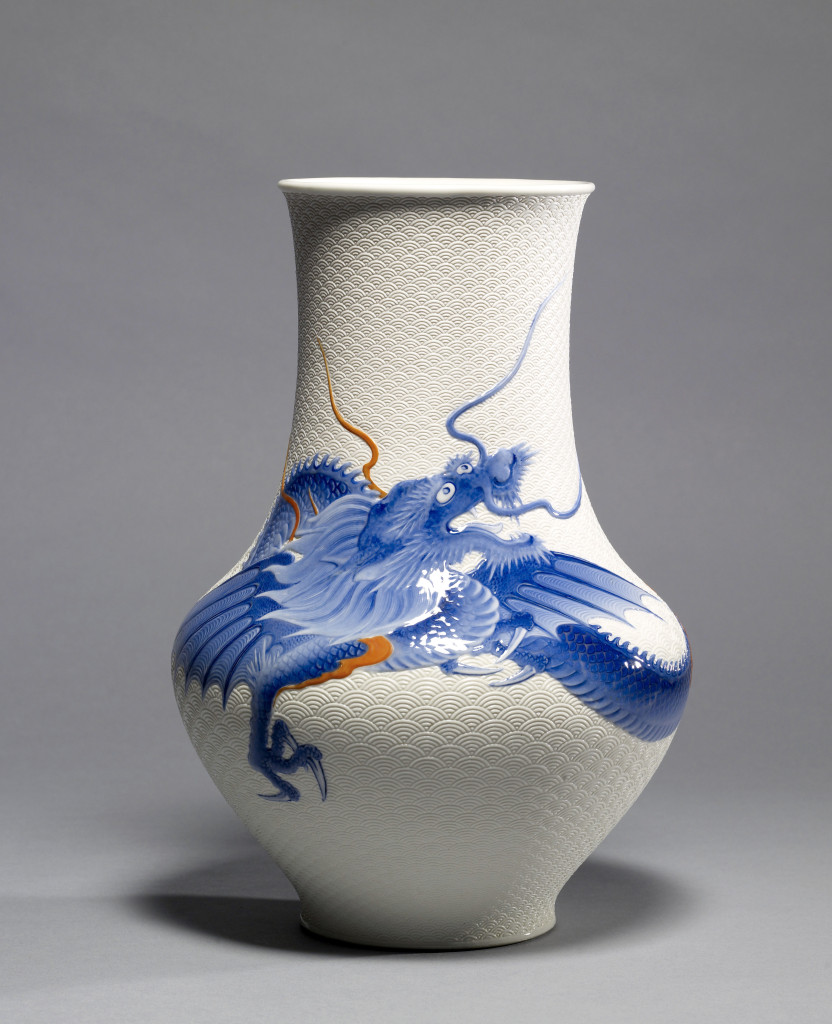

“In the Summerhouse” by George Tooker (American, 1920–2011), 1958. Egg tempera on fiberboard, 24 by 24 inches. Collection of the Smithsonian American Art Museum, gift of the Sara Roby Foundation. ©Estate of George Tooker. Courtesy of DC Moore Gallery, New York City.

As to the evolving critical appraisal of these wares, Hina Hirayama noted in her catalog essay “Words and Objects in the Japan Craze in Boston, 1880-1900” that during the Twentieth Century scholars tended “to dismiss the kinds of works that the Centennial introduced to wide popular embrace – Japanese export ware – as vulgar, insignificant or even un-Japanese. Only since the 1980s have Meiji-era decorative arts made for export to the West attracted interest from scholars who have reassessed them in the context of Japan’s modernization and participation in the global economy. Examples of these works from the high end of the quality spectrum, now admired for their technical achievement, are today coveted by collectors in Japan.”

Other world’s fairs touched on in the “JapanAmerica” exhibition and catalog include Chicago’s Columbian Exposition (1893), St Louis’s Louisiana Purchase Exposition (1904), San Francisco’s Panama-Pacific Exposition (1915), Philadelphia’s United States Sesquicentennial Exposition (1926), Chicago’s Century of Progress International Exposition (1933), New York World’s Fair (1939-1940), San Francisco’s Golden Gate International Exposition (1939), New York World’s Fair (1964-1965), Montreal’s Expo 67 and Osaka’s Expo 70.

Organizing curator Green is especially interested in Japanese influence upon American arts during the late Nineteenth and early Twentieth Centuries. She explained that “for many American artists it was the decorative arts that stimulated their imaginations. Americans embraced Japonisme with a vengeance, introducing it into both fine and decorative arts.” She called attention to the Childe Hassam painting “The Goldfish Bowl,” noting that the “tripartite division of the space recalls a folding screen” and that the canvas is a “culmination of what many American artists took away from their exposure to Japanese art while retaining an obviously Western setting.”

She likewise pointed out how Cincinnati artist and future founder of Rookwood Pottery Maria Longworth Nichols “visited the Centennial exhibition and was captivated by the Japanese bronzes and ceramics, and with Félix Bracquemond’s Service Parisien for Haviland & Co. of Limoges, with its intriguing underglaze painting of subjects from Hokusai’s manga.” Green observed, “I think this shows how forward thinking – and impressionable – Nichols was when she attended the Centennial. Her response was immediate and her Rookwood Pottery was one of the first to reflect this new sensibility to Japanese art. Rookwood’s success was a testament to her vision.”

European and American Japonisme is a perennially popular museum exhibition topic, in part because the objects are riveting. Through the exhibition and catalog, Green and her colleagues present a revisionist view of this often splendid, hybridized material and the ideas undergirding it. They also delve into the character, positioning and public reception of Japanese Modernist art and design within the realm of international relations, a novel subject for American museums.

Five years after his arrival in the United States, Bumpei Usui exhibited this cityscape at Philadelphia’s 1926 Sesquicentennial International Exposition. “14th Street” by Bumpei Usui (American, b Japan, 1898–1994), 1924. Oil on canvas, 30- by 24 inches. Collection of the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, J. Harwood and Louise B. Cochrane Fund for American Art. —©Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Katherine Wetzel photo

As an illustration of the latter, in the period immediately after World War II, Allied leaders encouraged the defeated Japan to portray itself less as an industrialized nation and more as a country where traditional arts and fine craftsmanship had long been treasured. They saw the high value placed on art in Japanese culture as something that all people could appreciate, a universal ideal that could promote healing and cooperation among former enemies.

Christopher Reed examines this strategy in his catalog essay “Aesthetic Diplomacy: ‘Creative Prints’ in the Postwar Era.” In it, he describes the special role a type of Twentieth-Century woodblock print called sosaku hanga played in encouraging understanding and respect between Americans and Japanese during the Occupation period. The writer James Michener, known for his stories about American personnel in the Pacific Theater, was their most famous champion. An avid collector, Michener included them in his 1959 book Japanese Prints from the Early Masters to the Modern.

An irony lay in the fact that sosaku hanga, translated as “creative prints,” were not produced in a traditional manner nor were they particularly prized in Japanese artistic circles where printmaking did not rate as a fine art. The Japanese artists who made sosaku hanga were students of the Western Arts and Crafts style woodblock printing and personally executed all the steps of the printmaking process. This approach contrasted with the customary Japanese method, wherein artists made the initial drawings and then turned them over to publishers who oversaw the realization of prints by woodblock carvers and printers.

Shields stated proudly that “JapanAmerica” “allows the Crocker Art Museum to introduce audiences to beautiful artwork that they may not know, while at the same time allowing us to put many of our permanent collection artworks into greater context…. This is truly one of the most stunning shows the Crocker has had the honor to present.”

In addition, visitors to the Crocker can experience two exhibitions relating to “JapanAmerica.” “Into the Fold: Contemporary Japanese Ceramics from the Horvitz Collection” is on view through May 7, while “Two Views: Photographs by Ansel Adams and Leonard Frank” opens on February 19. The latter marks the 75th anniversary of President Franklin D. Roosevelt signing Executive Order 9066, which led to the incarceration of more than 120,000 Japanese Americans in camps during World War II. Included are images Ansel Adams captured at the Manzanar Relocation Center in California and Leonard Frank’s visual documentation of a similar program of Japanese removal and internment that took place in Canada’s British Columbia. The photography exhibition closes on May 14.

The catalog for “JapanAmerica,” edited by Nancy E. Green and Christopher Reed, was published by the Herbert F. Johnson Museum, Cornell University in 2016. It is available through the Johnson Museum and sells for $35, plus shipping.

Crocker Art Museum is at 216 O Street. For information, 916-808-7000 or www.crockerartmuseum.org.

Kate Eagen Johnson is an expert in American decorative arts and an independent museum consultant, historian, lecturer and author.