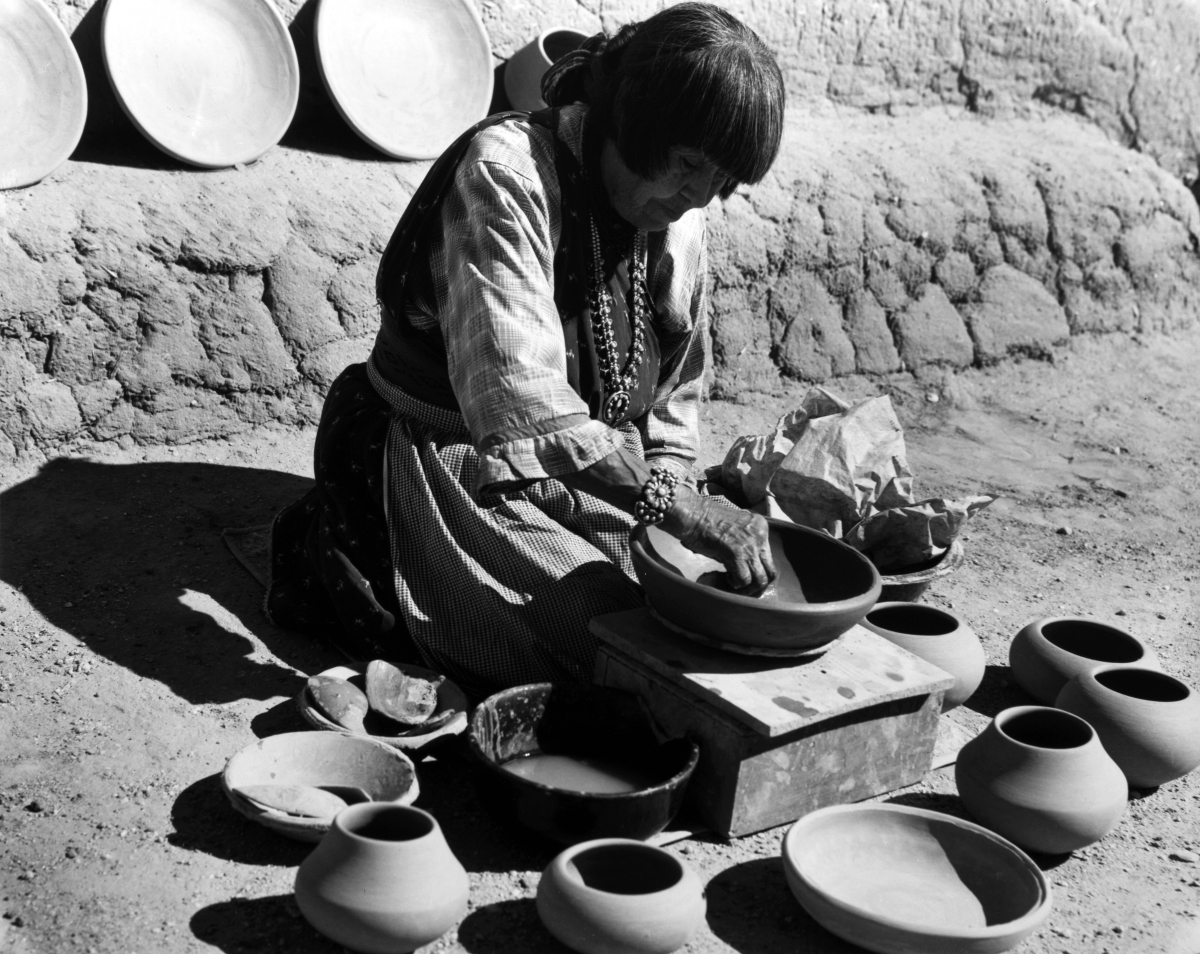

WASHINGTON, D.C. – The National Museum of Women in the Arts (NMWA) presents “New Ground: The Southwest of Maria Martinez and Laura Gilpin,” from February 17 through May 14. Contemporaries and friends, potter Maria Martinez (circa 1887-1980) and photographer Laura Gilpin (1891-1979) shaped the image of the Southwest as a culturally rich region through Martinez’s bold adaptation of an ancient black-on-black pottery design technique that reflected her Pueblo artistic traditions; Gilpin, hailed during her lifetime as the “grand dame of American photography,” was one of the first women to capture the landscape and peoples of the American West on black and white film.

“New Ground” features 26 works of pottery by Martinez and 48 platinum, gelatin silver and color print photographs by Gilpin, drawn primarily from the Eugene B. Adkins collection at the Philbrook Museum of Art, Tulsa, Okla., which organized the exhibition, and the Fred Jones Jr Museum of Art at the University of Oklahoma, Norman, Okla.

Maria Martinez and Popovi Da, polychrome olla, 1966, polychrome pottery, 8½ by 10½ inches in diameter.

“‘New Ground’ counters dominant Nineteenth and Twentieth Century narratives that typically cast the American West as a masculine place of staged romance or rugged conquest,” said NMWA director Susan Fisher Sterling. “The exhibition explores how Martinez and Gilpin refined the image of a modern Southwest during the mid-Twentieth Century as a space for communal creativity and connection.”

Martinez lived at San Ildefonso Pueblo, north of Santa Fe, N.M. Together with her husband, Julian, Martinez revived an ancient method of making black-on-black pottery. She traveled throughout the United States to demonstrate the technique for making her sleek, thin-walled ceramic vessels, creating a wide demand for her work, which is still sought-after today. She was one of the first Pueblo artists to sign her works, examples of which are found in collections across the globe. Her work inspired generations of artists, including her own family, several of whom still produce pottery at the San Ildefonso Pueblo.

Gilpin was born in Colorado and studied photography in New York at the Clarence H. White School from 1916 to 1917. She was drawn back west, by her own account, to be in the “mountain country” where she felt she belonged. She is best known for her documentary prints, which include aerial landscapes and intimate portraits, images that capture the geological marvels of the landscape, as well as the fine details on the faces of her sitters. Over six decades, Gilpin documented the Southwest and its people, experimenting with a variety of photographic techniques and styles to capture her own connection to the region.

Martinez’s pottery is formed from and decorated with clays dug from the earth near her home. Stylized depictions of local flora and fauna, as well as mythical creatures like Avanyu, a feathered serpent and water guardian, are found on many of the works on view. Other motifs include birds, road runner tracks, rain, feathers, clouds and mountains.

Maria Martinez and Popovi Da, black-on-black jar with Avanyu, 1957, polished blackware pottery with matte slip paint, 15¾ by 19 inches in diameter.

Gilpin captured the landscape of the West on film and commented – through her imagery and her writings – upon the interconnectedness between the environment and human activity. Hefting heavy camera equipment, Gilpin trekked great distances by foot, jeep or plane to reach remote locations in pursuit of views, often flying dangerously low in airplanes to achieve her aerial shots. Unbounded by physical risks and societal restrictions, Gilpin pursued photography in the Southwest well into her eighties.

Initially encouraged by Edgar L. Hewitt and Kenneth Chapman from the nascent New Mexico Museum, Martinez developed a distinctive style of pottery that continues to resonate among artists today. Her relationships with family, community members, friends and collectors profoundly shaped her creative life. She collaborated with her husband, sons (particularly Popovi Da), daughter-in-law and grandson. In keeping with the collective principles of the Pueblo, she also signed her name to works made by others so that all might share in the benefits of her popularity.

Gilpin was the daughter of a Western adventurer, and she felt deeply connected to the landscape and described her compulsion to document its rugged terrain. She considered herself a landscape photographer, but her photographs chronicling people and their activities are perhaps her most distinctive work. She focused her lens on the American life she came to know among the Pueblo and Navajo peoples.

The National Museum of Women in the Arts is at 1250 New York Ave NW. For further information, 202-783-5000 or www.nmwa.org.