A copy of this print was one of eight Baumann entered in the 1915 San Francisco World’s Fair. The Indiana farm scene was part of his large-format “Schoolhouse” series, which he hoped would be installed on Indiana classroom walls as inspiration to students. “Plum and Peach Bloom,” 1912. Color woodcut, 19¾ by 26-5/8 inches. From the collection of the Two Red Roses.

By Kate Eagen Johnson

PASADENA, CALIF. – Certain artists are identified with particular regions. Consider Thomas Cole and the Hudson Valley, Grant Wood and the Middle West, Winslow Homer and New England. When art lovers hear the name of Gustave Baumann (1881-1971), visions of the American Southwest typically spring to mind. Through “Gustave Baumann in California,” an exhibition on view at the Pasadena Museum of California Art (PMCA) through August 6, guest curator Susan Futterman invites us to expand our horizons beyond images of adobe buildings and high desert landscapes dotted by chamisa and cottonwood and appreciate the printmaker’s love affair with another part of the country.

It is clear that woodcut artist Gustave Baumann reveled in “the power of place.” He was all about capturing “genius loci,” an ancient Roman term that originally signified an actual spirit guarding over a spot, but which was later broadened to refer to the defining spirit or character of an area. Baumann’s creation of accurate yet atmospheric depictions of a locale’s topography, flora and fauna stands as one of his artistic hallmarks.

Born in Magdeburg, Germany, in 1881, Baumann immigrated with his family to Chicago at age 10. In 1895, his father left the family, prompting the young teen to drop out of school and find employment in a commercial engraving shop. He subsequently set up his own engraving house while also attending the School of the Art Institute of Chicago at night. Desirous of pursuing printmaking as a fine art rather than as commercial illustration, Baumann traveled to Germany to study at Munich’s Kunstgewerbeschule (School of Arts and Crafts) during the years 1904 and 1905. He returned to Chicago, and then relocated to Brown County, Ind., in 1910. There, for the next half decade, he devoted himself to depicting rural scenes and scenery.

After a few months spent in New York State and Massachusetts, Baumann turned his gaze westward in 1918. He went first to Taos, N.M., and then on to Santa Fe, where he settled. Over the years, he and his wife Jane became leaders of the town’s growing arts community. They created the “Marionette Theater” with Gustave using his woodcarving skills to fashion marionettes and Jane dressing them and writing the plays. It was Baumann’s idea to build and burn a large-scale puppet named Zozobra (Old Man Gloom) as part of Fiestas de Santa Fe, a ritual that continues to this day.

After a few months spent in New York State and Massachusetts, Baumann turned his gaze westward in 1918. He went first to Taos, N.M., and then on to Santa Fe, where he settled. Over the years, he and his wife Jane became leaders of the town’s growing arts community. They created the “Marionette Theater” with Gustave using his woodcarving skills to fashion marionettes and Jane dressing them and writing the plays. It was Baumann’s idea to build and burn a large-scale puppet named Zozobra (Old Man Gloom) as part of Fiestas de Santa Fe, a ritual that continues to this day.

Baumann famously wanted to offer the public “good pictures at low cost,” and sold prints for $5 and $10. (In today’s market, individual prints fetch four and five figures.) Throughout his career as a fine printmaker, Baumann made sketching excursions. While held spellbound by the dramatic environment of Santa Fe and environs, he was also drawn to the spectacular Pacific seacoast.

The PMCA exhibition showcases examples of Baumann’s preparatory studies in pencil, gouache and tempera, carved woodblocks, progressive proofs and finished woodcuts. A Midget Reliance proof printing press similar to the one the artist employed stands in the gallery. His carving tools can also be inspected.

The exhibition begins with copies of the prints Baumann entered for display at the 1915 San Francisco Panama-Pacific International Exposition. They are a fitting introduction, since Californians first learned about this artist and his work through them. Baumann won a Gold Medal for these depictions of Indiana, which included selections from his “In the Hills o’ Brown” portfolio and the so-called “Schoolhouse” series. California artists William S. Rice and Frances Gearhart saw Baumann’s color woodcuts at the world’s fair, and a print by each is included to illustrate his impact upon their work. Of course, Baumann’s 12 prints of California scenery and associated preparatory works and variants serve as the exhibition’s main event. This art cache is the culmination of seven auto sketching trips Baumann took through California between the years 1925 and 1938.

_baumann_highres.jpg)

Baumann’s chop, featuring a hand within a heart, recalls his saying, “What you put your hand to, you put your heart behind.” “Point Lobos,” 1936; printed in 1949. Color woodcut, II 50/125 ‘49; 8-1/8 by 8-1/8 inches.

In conversation, Susan Futterman related how the idea for the exhibition came from Gala Chamberlain of Annex Galleries in Santa Rosa, an expert who leads the Baumann catalogue raisonné project. When touring PMCA’s “Behold The Day: The Color Block Prints of Frances Gearhart” (2009-2010), Chamberlain mentioned to the show’s curator Futterman and then-PMCA administrator Jenkins Shannon that Baumann had produced a group of California images that would make a lovely exhibition. Some years later, Shannon queried Futterman if she recalled Chamberlain’s remark. Futterman stated, “I called Gala and asked, ‘How much is there? Is there enough to make a show?’ It turned out there was actually too much!”

Futterman comes to print curation via an indirect route. When encouraged to elaborate upon the statement “this is my retirement occupation,” she shared, “I was director of Broadcast Standards and Practices for ABC Television for 30 years. I have always been interested in art as my stepfather was an art dealer by the name of Frank Perls in Beverly Hills and his brother had the Perls Gallery in New York. Frank dealt [in] … Picasso and Matisse and also focused on California artists, such as Howard Warshaw, William Brice, Rico Lebrun and Channing Peake. I live in Pasadena, which is the bastion of the American Arts and Crafts Movement as well as being the home of many California plein air Impressionists from the same period. … I was taken by the work of Frances Gearhart at an antiques show. When I found out that she was from Pasadena, but I had never heard of her, I had to find out her story.”

This guest curator hopes visitors will better understand the process of woodblock printing after experiencing the exhibition. She explained, “Usually at museums visitors see the finished print – the end product – but we wanted to break it down for the viewer. For example, with ‘Monterey Cypress’ we show a graphite drawing, two tempera studies in different color schemes and then the print. A year later, Baumann reversed the print so that it took on the orientation of the original drawing and added three sea lions with aluminum leaf in the background. Aluminum would not oxidize or tarnish. It is not silver leaf as some think. In regard to the print known as both ‘Singing Woods’ and ‘Singing Trees,’ there are two different states representing two different color schemes and a selection of five progressive prints along with some of the carved blocks.”

As described in the exhibition brochure, while studying in Munich, “Baumann learned to carve and impress blocks using techniques based on the German manner, with broad, flat areas of color applied directly adjacent to one another and uninterrupted by black key-block outlines. He also learned how to run blocks through a printing press, contrasting the Japanese style most American printmakers implemented, in which artists would brush colors directly onto the blocks and then hand rub rather than use a press to create the resulting print.”

Baumann’s sketching trips allowed for his close observation of nature. Futterman noted that “the print ‘Redwood’ resonates with me as a Californian because of his treatment of the redwoods. Usually you see straight trunks and you see them standing like soldiers. His treatment is more lyrical with a sapling in the middle showing foliage. … And there are the wonderful mossy-covered mounds seen with redwoods. He sat there and drew them. It feels intimate. He has taken you right into the middle of a redwood forest.”

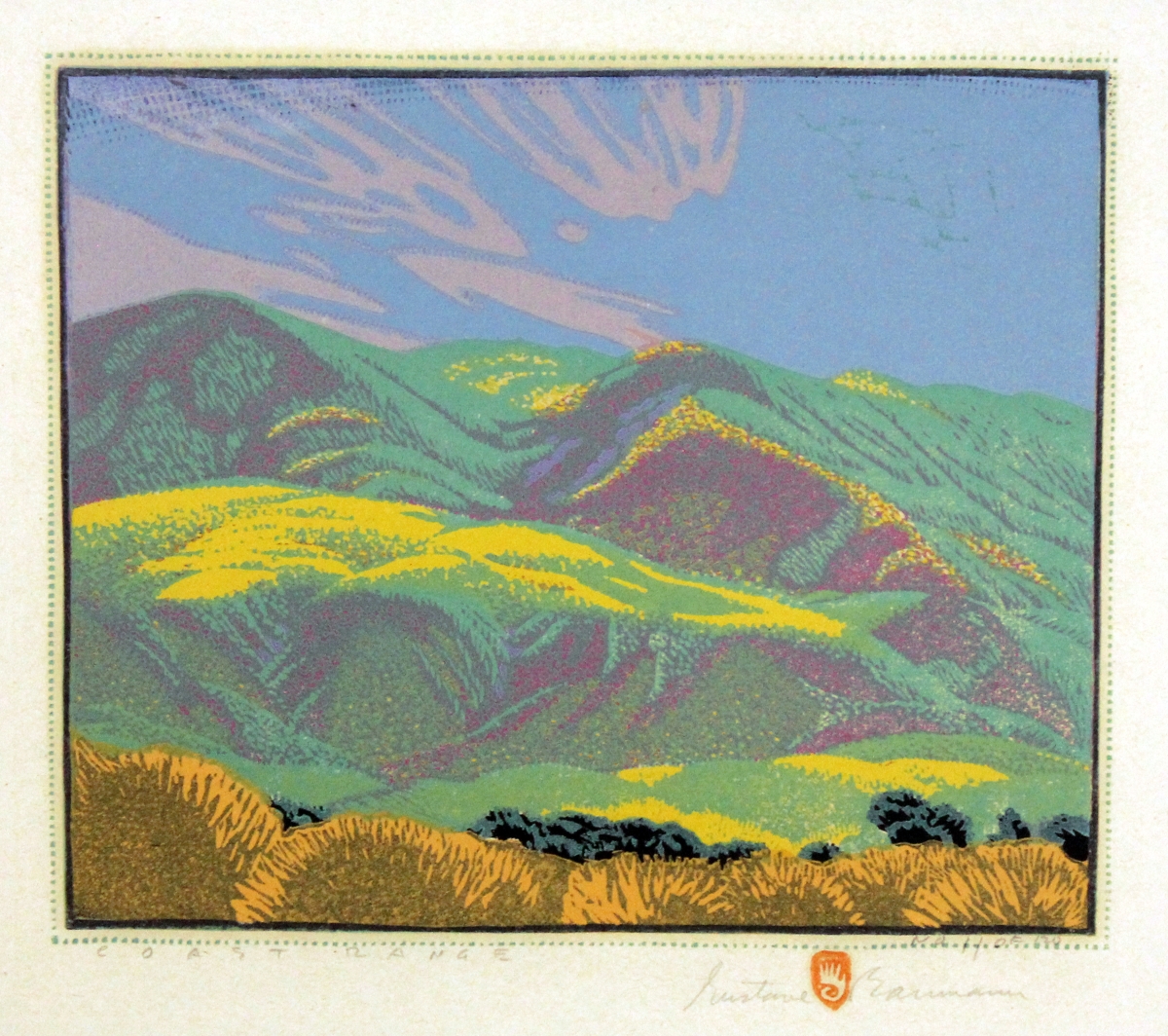

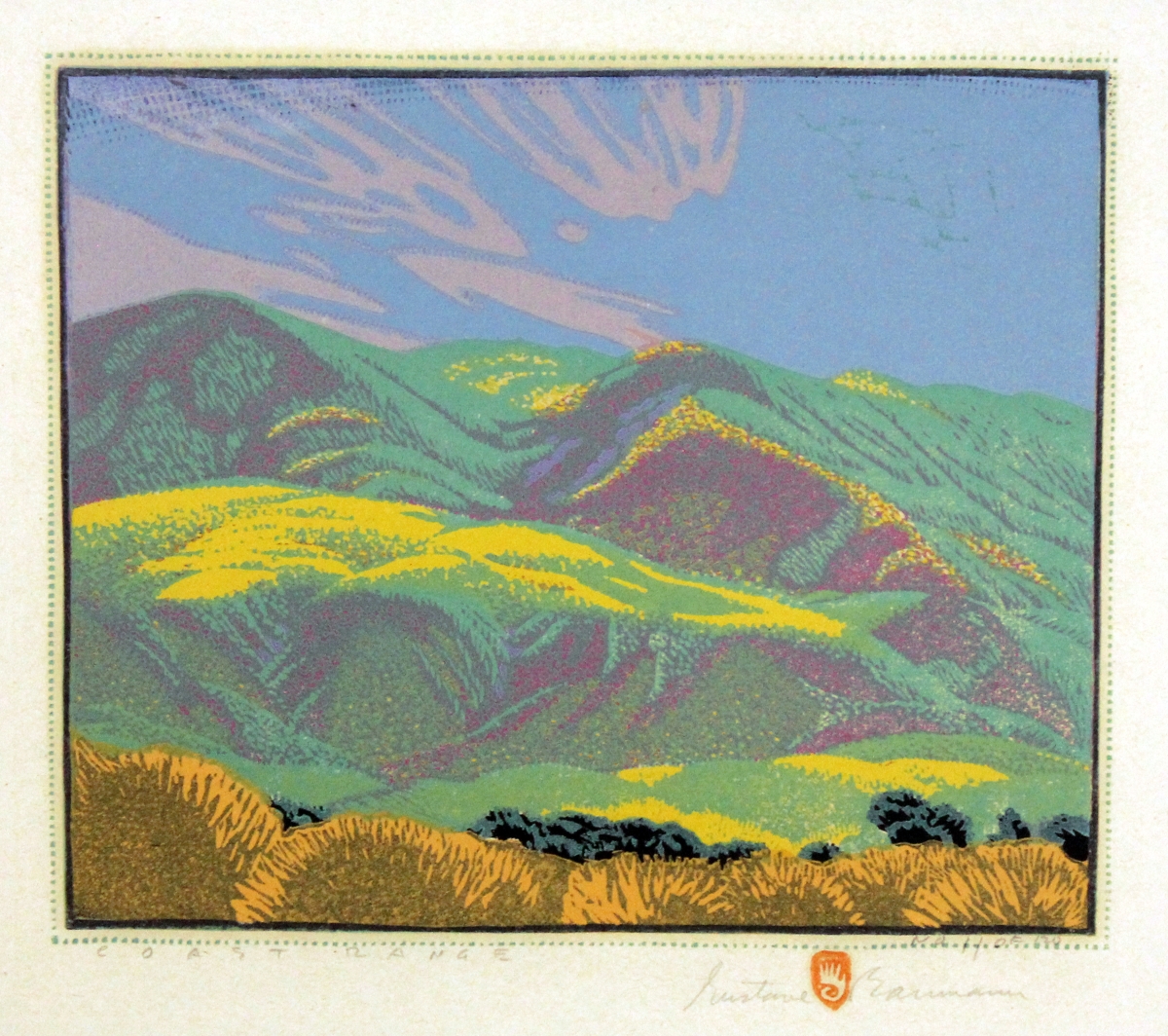

The artist was in his forties and fifties when he made his California sojourns, and Futterman underscored the artistic confidence so evident in his California prints. She pointed to “Coast Range” where the hills are “soft and undulating. Something you don’t think of with Baumann’s work. He is brave and mature at this point.” She also called attention to “Pelican Rookery,” where Baumann depicted a few birds resting on a rock in the ocean. “Baumann makes a detail … this is more like a painting than a print.” She stressed that “it is not a ‘whole view’ as a younger artist might be inclined to make.”

Interest in Baumann and his color woodcuts, which rarely seems to wane, has also been bolstered by the sweeping retrospective “Gustave Baumann, German Craftsman – American Artist” mounted at the Indianapolis Museum of Art in 2015 and 2016. IMA’s curator of prints, drawings and photographs Martin Krause produced the exhibition. In conjunction with it, he annotated and edited The Autobiography of Gustave Baumann, a generously illustrated volume published by Pomegranate in 2015.

PMCA’s “Gustave Baumann in California” will appeal to admirers of Arts and Crafts design, print collectors, working printmakers and those captivated by California’s dazzling scenery. The particular genius of this master printmaker and superb colorist shines through this focused exhibition.

The exhibition is accompanied by a brochure.

The Pasadena Museum of California Art is at 490 East Union Street. For information, 626-568-3665 or www.pmcaonline.org.

Kate Eagen Johnson is an expert in American decorative arts and an independent museum consultant, historian, lecturer and author.

_baumann_highres.jpg)

_baumann_highres.jpg)

_26_of_120_baumann_highres.jpg)

_baumann_highres.jpg)