By Richard M. Candee

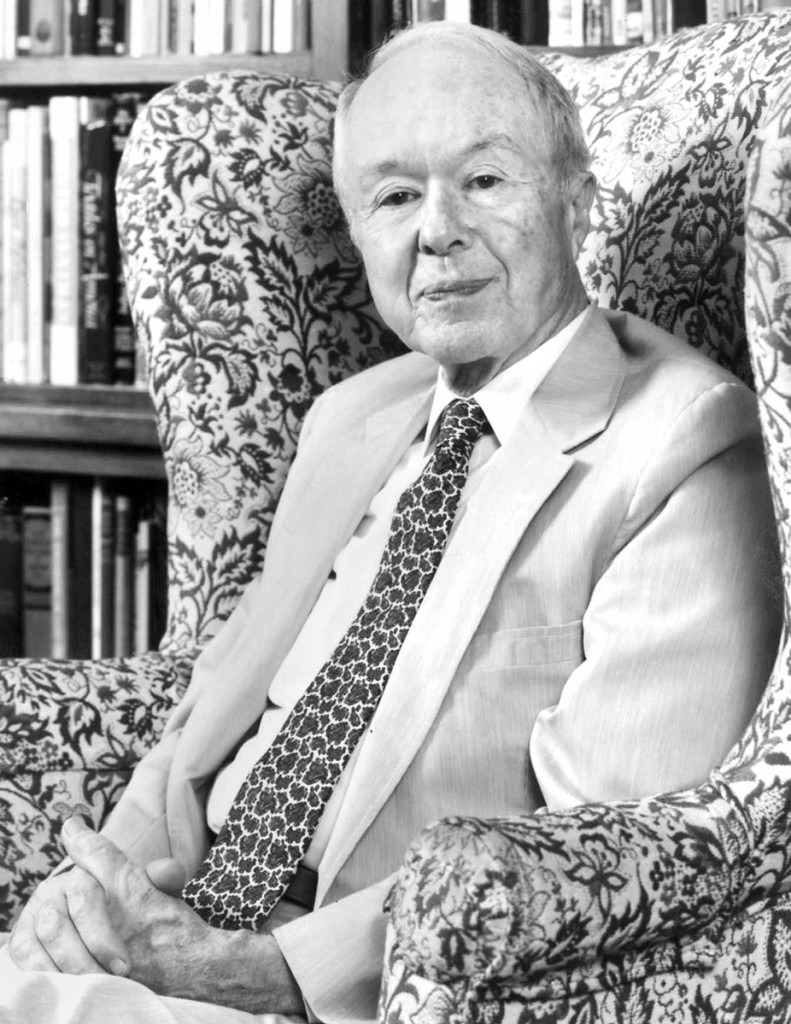

HADLEY, MASS. – Abbott Lowell Cummings, the leading authority of Seventeenth and early Eighteenth Century (“First Period”) architecture in the American Northeast and author of The Framed Houses of Massachusetts Bay (Harvard University Press, 1979) died early May 29 at age 94 at the Elaine Center in Hadley. An outstanding teacher at Boston University, Yale University and the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, Cummings, who mentored dozens of young scholars, asked me many years ago to memorialize his life and scholarship when the time came.

Born in St Albans, Vt., on March 14, 1923, the son of a Congregational minister and sometimes supporter of Norman Thomas, he spent much of his youth with his beloved paternal grandmother in Southington, Conn. This old Yankee helped to form his love of genealogy and appreciation of New England’s past. It was she, too, who gave the teenager a membership in the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities (SPNEA), now called Historic New England.

The budding art historian was educated at the Hoosac School (1936-1941), Oberlin College (BA 1945, MA 1946) and Ohio State (PhD 1950), then one of the few universities offering American architectural history. He soon learned discretion in speaking of his research when, in 1948, Professor Henry Russell Hitchcock published without credit Cummings’ new discoveries on the design and building of the Greek Revival Ohio capitol.

From 1948 to 1951, he taught at Antioch College, while finishing his critical study of the Federal-era building guides of architect Asher Benjamin. Thereafter, he accepted a position as assistant curator for the American Wing of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. In 1955, he was hired as assistant director of SPNEA and editor of its journal Old-Time New England.

I met Abbott Lowell Cummings in the early 1960s when I was an Oberlin sophomore in a summer program at Historic Deerfield on a fast-paced tour of Boston’s buildings. Given our mutual history at Oberlin, he encouraged me to seek out his old professor, Clarence Ward, and urge him to give me a class on American architecture. It set me on my own career in architectural preservation.

At Oberlin in September 1946, his master’s thesis, “Documentary Histories of Seventeenth Century Houses in Massachusetts Bay,” noted that stylistic consistency over the Seventeenth Century and a time “lag” for adopting new design ideas “are confusing to the historian in his attempt to establish a system of dating for the houses of the Seventeenth Century.” He carefully sifted through the documentary evidence of 70 houses – many of them no longer standing – in the Commonwealth, with detailed notes on the “condition” and plan development for those still extant. This was followed, in typical Abbott Cummings fashion, by an appendix of ten building contracts and similar documents, and a full secondary bibliography.

I mention this first attempt at his favorite topic to show how long ago his Framed Houses actually began. Over the next 34 years, Abbott continued his research about what really happened to these (mostly) surviving houses and what changes in structure or style occurred. Certainly, that is what he was doing while he worked at the American Wing of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City from 1951 to 1955, documenting all the rooms that George Francis Dow helped install in the 1920s.

After joining the SPNEA, he was allowed one day a month for personal research to delve into not only the oldest surviving houses but documents underpinning both his Framed Houses and other books and articles on bed-hangings, probate inventories and wallpaper.

What most folks never knew was that Abbott thought he had his masterwork nearly completed sometime in the late 1960s. He had all the documents, had been to see all the houses in the Bay Colony and had large chunks of writing well advanced. He had also searched out some of the (virtually unstudied) English buildings of the early Seventeenth Century that might have provided prototypes for Massachusetts work.

He and I spent several summer vacations trotting around England during the late 1960s and early 1970s looking at areas where “his” carpenters had come from, seeking out his famous “prototypes” – houses sharing similarity of form or construction to the earliest Massachusetts Bay homes. We spent several summers in the hands of Freddie Charles and his family, one summer looking at examples with Ron Brunskill and another year attending a Vernacular Architectural Forum meeting and tour with all the early Vernacular Architectural Group members. His particular interests brought new attention to the Seventeenth Century timber-framed vernacular style that British scholars had considered one of the less interesting periods.

There, too, in the late 1960s he met Cecil Hewett, the secondary school art teacher with an antiquarian bent for drawing the structural joint systems of timber-framed buildings. Hewett revolutionized the dating of those English buildings by developing a theory about the chronology of various timber joints and how they “evolved.” This eventually led Hewett to a position with the Greater London Council Buildings Division in 1972.

In what I always considered one of the clearest acts of intellectual honesty, Abbott essentially threw out his old manuscript and, getting a grant to bring the whole Hewett family over to Massachusetts for a summer, revisited all the major houses so Hewett could draw their framing details and educate Abbott about framing in this new theoretical system that linked the New World to the Old.

If computers had been more advanced in the early 1970s, we might also have had a chance at tree-ring dating in Framed Houses. It has always been a disappointment that his discovery of the 1590s droughts in the chimney beam of the 1660s Gedney house in Salem, Mass., did not evolve as easily into the general practice of dendrochronology that we know today. He saw it clearly as a potential, but the conservatism of the New Mexico experts who claimed New England’s weather was too “complacent” for measurement killed the idea for two decades before the coming of computers.

His intense study area was only Massachusetts Bay Colony with its great abundance of First Period buildings – more perhaps than anywhere outside Europe. And, as he remained somewhat secretive and justifiably paranoid that someone would scoop his research, he was perfectly happy to let others explore the Seventeenth Century houses elsewhere in the state and region.

Thus in the mid-1960s when Cary Carson, a young Harvard graduate student, and I were both hired to explore the Seventeenth Century architecture of Plymouth Colony for Plimoth Plantation museum, I replicated Abbott’s method of looking at the documents and tried to find patterns from the surviving houses and their inventories. He published my “Documentary History” of Plymouth’s early buildings in Old-Time New England. He also “gave” me my dissertation topic, the very few First Period wooden buildings of Southern Maine and New Hampshire, because they wouldn’t conflict with his study.

Cummings always claimed that his was “an old-fashioned” history of the subject. Its geographic specificity, Massachusetts Bay, did make Framed Houses into something akin to Norman Isham’s studies of Rhode Island and Connecticut’s earliest buildings written much earlier in the Twentieth Century.

Taking over as executive director of the SPNEA in the difficult 1970s and 80s, he also helped form the American and New England Studies Program at Boston University.

His interest in geographic specificity of early timber framing continued when Cummings was lured to Yale University as the Charles F. Montgomery professor of American decorative arts (1984-92). Both Connecticut and New Netherlands offered whole new areas of inquiry into buildings of which he might ask the same questions but elicit different results. I vividly remember a wonderful symposium at Yale where John Demos conjured a mythical Dutch Carpenter named “von Cummins” to help explicate all the Dutch influences on Connecticut framed buildings.

Retiring from Yale to a home in South Deerfield, Mass., with his sister’s family, he spent his early retirement compiling the Descendants of John Comins (ca. 1668–1751) and his wife, Mary… (Newbury Street Press, 2001). His grandmother had instilled a genealogical interest and Cummings served from 1970 to 1973 as a trustee of the New England Historic Genealogical Society, writing many articles in its magazines, and as a council member after 2004.

In early retirement, he taught again for two years at Boston University and at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, from which he received an honorary degree in 1998. He was also recognized with the Henry Francis du Pont Award, and awarded honors for his scholarship by the Traditional Timber Frame Research Group, the Vernacular Architecture Forum, the Connecticut Trust for Historic Preservation and the American Society of Genealogists.

He was a life member of SPNEA, the Bostonian Society, the Fairbanks Family in America and the Southington Historical Society; a Massachusetts Historical Society Fellow, an honorary member of the Colonial Society of Massachusetts, and served on many boards and overseers’ committee, including that of Plimoth Plantation, the Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association and Historic Deerfield. He remained a life member of the Ancient Monuments Society, an elected member of Society of Antiquaries of London, the American Antiquarian Society, the British Vernacular Architecture Group and founding president of the Vernacular Architecture Forum, whose highest prize for scholarship remains its Abbott Lowell Cummings Award.

Abbott is survived by his devoted nieces and nephews: Abigail Cummings of Arlington, Va.; Carla Cummings of New York City; Jonathan Cummings Jr. of Bethesda, Md.; Justina Golden of Florence, Mass.; and Scott Cummings of Austin, Texas.

Donations in his honor may be made to the New England Historic Genealogical Society, 99-101 Newbury Street, Boston MA 02116.

Richard M. Candee is professor emeritus of the American and New England Studies and Preservation Studies programs at Boston University.

Abbott, at one time a neighbor and later a trustee of Historic Deerfield, was a dear friend. I first met him in 1965 and last saw him three weeks ago. After Grace and I left Deerfield in 2005, he was our frequent guest in Salem. He was always great company, with a fund of stories, wonderful powers of description and tremendous humor. Professionally, he had the instincts of an antiquarian and the scholar’s determination to find every bit of evidence to support his premise. He set high standards for himself and others. In 1957, he was elected to the Colonial Society, which in 1979 published his study Architecture in Colonial Massachusetts. It is still widely read.

-Donald Friary, president, Colonial Society of Massachusetts, and director emeritus of Historic Deerfield

Well before the term ‘historic preservation’ came into vogue, New Englanders were saving old houses. We think of Boston’s William Sumner Appleton (1874-1947), who founded the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities (SPNEA) in 1910. Abbott was very much in the mold of Appleton: passionate about old houses and their enormous value as historical documents.

-Grace Friary, media consultant

Abbott Cummings combined two, or make that three, characteristics that most of us do not possess: the pursuit of intellectual inquiry at a level that defines reputation and stature, the ability to influence and even awaken in people interests sometimes unknown to them and the capacity with language to bring, heaven forbid, entertainment or, better yet, a hilarious story to all of the above. Abbott “holding court” was a great way to learn history of all sorts and to solve the problems facing the front ranks of historic preservation.

-Philip Zea, president, Historic Deerfield

In the museum business, and most others, there are a lot of passengers on the bus. We can’t all be leaders and visionaries, but boy do we ever need them. The quality Abbott had is the rarest of rare – maybe 500:1. When we talk about the rise and fall of public interest in historic preservation and antiques, isn’t the solution people like him? Abbott conveyed warmth and delight, qualities that – when conjoined with conviction, scholarship and talent – work magic.

-William Hosley, principal, Terra Firma Northeast

My memories of Abbott are so vivid. I see him in the classroom sharing his love of architecture. I follow him in the attic of an early house as he leads an unforgettable tour of Seventeenth Century building practices. I hear him telling one of his famous stories of the Curtis sisters of Beacon Hill. These images remain real and immediate, though they date back to the 1970s, 80s and 90s. Everyone Abbott met will have their own recollections. His accomplishments and impact are legendary. In my case, I have never known a better teacher, more compelling architectural guide and more gifted storyteller. He was unique–and will be greatly missed.

-Brock Jobe, professor emeritus, Winterthur Museum

The Gedney House in Salem, Mass., is the one to understand him by. It is not about furnishing, it is about framing and how one peels off and reveals the evidence. If you want to recreate an environment where you see Abbott getting most excited, the Gedney House is it.

-Edward S. Cooke Jr, Yale University, 1998