Harold Holzer and his wife Edith at the gala reception for “Lincoln and New York” at the New-York Historical Society.

Harold Holzer is a scholar of Abraham Lincoln and the political culture of the American Civil War era. He won the Gilder Lehrman Lincoln Prize and four other awards in 2015 for his book, Lincoln and the Power of the Press. In 2015, after 23 years of service, Holzer retired from his post as senior vice president for public affairs at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. He joined Roosevelt House that September as its Jonathan F. Fanton director. There, he directs academic programs for Hunter College undergraduates in public policy and human rights, and hosts public programs on history and current events. Holzer will receive the 2017 Empire State Archives and History Award from the New York State Archives Partnership Trust at a public program on September 6 at The Cooper Union in New York City. Meanwhile, a recently opened exhibit at Roosevelt House – “The New Deal in New York City, 1933-1943” – chronicles the vast range of public projects funded by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s administration over its first ten years. It will run to August 19.

What are the lessons from the New Deal programs like the Works Progress Administration?

The message of our show is both the enormity of New Deal public works and arts programs – and the powerful reminder that, at its best, government really can make a difference, both in putting people to work and in dramatically changing the cityscape and landscape of this country. In other words, here is the still-relevant model for the urgently needed “infrastructure improvements” that we have been hearing about since the presidential campaign last fall. Once upon a time, we need to remember – in economic times far worse than our own – a president and a Congress, working together, put Americans to work and modernized the country in the process.

What was the impact of such programs to a nation that was reeling from the Great Depression?

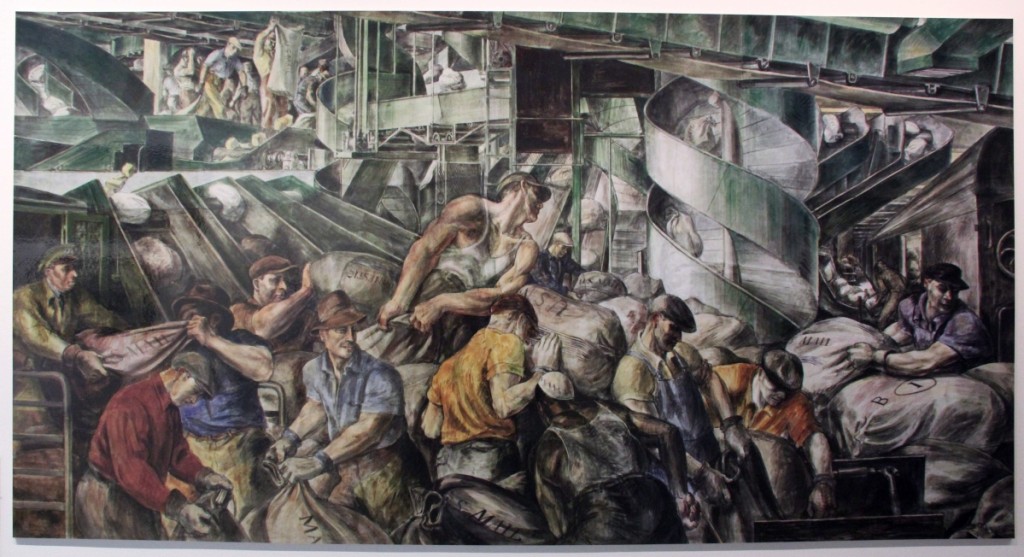

Of course, one great impact was enhancement of morale. FDR told Americans they had nothing to fear but fear itself, and announced he would try any and all programs to cut joblessness. The nation’s spirits seemed to lift overnight. Within a decade, the tangible results were manifest, too. These programs transformed cities and towns across the country. In New York City alone, the focus of our new show, more than 1,000 individual projects got underway: new buildings for Hunter College and Brooklyn College, the Triborough Bridge, LaGuardia Airport, public housing, the Lincoln Tunnel, murals in post offices and hospitals – projects that put artists to work, too – giant swimming pools for low-income neighborhoods and subsidies for out-of-work playwrights and actors to go back to inspiring and enlightening us. It was transformative, and most of these projects still exist. FDR directed some 7 percent of all federal project funding to New York City. Thank goodness.

With your background in journalism and your most recent book, Lincoln and the Power of the Press (2014), what is your assessment of the relationship between media and government institutions today?

Every new presidential administration invariably comes to believe that the press is treating it worse than any journalists have ever treated any occupant of the White House. Bad as the current so-called “relationship” between government and the media may seem, the truth is that it’s been far worse in the past. During the Civil War, for example, Lincoln curtailed freedom of the press to an extent without precedent before or since. Some 200 anti-administration newspapers were shut down, editors were arrested and jailed without trial, printing presses were confiscated, newspaper offices occupied, and some pro-Democratic papers were denied access to the US mails to reach their subscribers. The fine line between dissent and treason seemed to vanish – though, of course, suspension of the precious writ of habeas corpus in times of rebellion was authorized by the Constitution. The Vietnam War era was pretty chilling for journalists, too, and the relationship between government and the press was often terrible. Fake news isn’t new, either – but that’s another story. The big problem is, our historical memory is vanishing. President Trump doesn’t seem to know much about our past, and today’s grade-school and high school students are taught even less. We’ve accepted this sense that things have never been worse because we’ve neglected to nourish our citizens with the perspective that used to be the essential element of our civics education. And that perhaps is the scariest thing of all.

You are a prolific writer, lecturer and radio and television authority; what’s next?

I’m working right now on a biography of Daniel Chester French, the sculptor of the Lincoln Memorial. I’ve never written a cradle-to-grave biography before – of anyone, not even Lincoln – or a book about an individual artist. I’m thrilled that Chesterwood, the beautiful Massachusetts summer home where French produced many of his great later works – including Lincoln – commissioned this project. Next on the docket is a book on Lincoln and immigration. It’s high time to look at how an earlier, equally anxious generation of Americans dealt with the thorny issue of foreign immigration.

-W.A. Demers