Tramp art keepsake box with hand and hearts, United States, late Nineteenth to early Twentieth Century. Courtesy of Robin Small. —Clare Britt photo

By Karla Klein Albertson

SANTA FE, N.M. — Anyone who has been to an antiques show featuring American folk art has seen examples of the distinctive woodcarving technique known as tramp art, produced by notch carving and cleverly layered scraps of wood. Artifacts of this type range from the simplest notched picture frames to fantasy furniture requiring a high level of skill and an enormous amount of time. The best practitioners rise to the level of self-taught sculptors. The motivation behind these creations often seems personal. Sometimes without kit or plan to guide them, the makers are often impelled by lifelong values and heartfelt religious, patriotic or romantic sentiments. The examples, whether intricate or plain, are truly folk art because they meant something to the folk who made them.

At the Museum of International Folk Art, “No Idle Hands: The Myths and Meanings of Tramp Art” presents more than 150 examples of the genre in an exhibition, on view through September 16, with accompanying catalog. Most of the pieces were made in the United States, but the show also features constructions from other sources in North and South America, as well as from Europe. The objects are drawn from the museum’s recently expanded holdings in this branch of folk art as well as loans from public and private collections. It has been more than 40 years since collectors first became aware of this type carving through an exhibition at what was then the Museum of American Folk Art and the 1975 publication of Tramp Art: An Itinerant’s Folk Art by Helaine Fendelman, a collector and antiques authority who lives in New York City.

Laura Addison, curator of North American and European folk art at the Santa Fe museum, set out to explore the variety, artistry, authorship and motivation behind the production of tramp art. In her catalog introduction, she writes, “The Golden Age of tramp art, the 1870s through the 1940s, was an era that valued industriousness and scorned idleness…. A creative pursuit of pragmatism and thrift, tramp art was an art of the working class.” While fully acknowledging that collectors either love it or hate it, she continues, “This volume endeavors to win over hearts and minds; dismantle misperceptions; update what is known about the who, what, when and where of tramp art; and cultivate an appreciation of an art form that is as thought-provoking as it is enduring….”

Addison has chosen an excellent title, for the avoidance of “idle hands” has been a driving motivation for many forms of folk art. They may or may not be the devil’s workshop, but empty fingers cry out for occupation. Humans seem to need “something to do” with their hands. In the past, men and women would crochet, hook rugs or engage in woodworking projects while listening to the evening radio programs. Workers sought to keep busy in the off seasons of the agricultural and construction cycle. Even today people play games on their phone or thumb type messages as they simultaneously stream television shows. Whether the solution is worry beads or eating popcorn, we have difficulty sitting in silence with empty hands.

Addison has chosen an excellent title, for the avoidance of “idle hands” has been a driving motivation for many forms of folk art. They may or may not be the devil’s workshop, but empty fingers cry out for occupation. Humans seem to need “something to do” with their hands. In the past, men and women would crochet, hook rugs or engage in woodworking projects while listening to the evening radio programs. Workers sought to keep busy in the off seasons of the agricultural and construction cycle. Even today people play games on their phone or thumb type messages as they simultaneously stream television shows. Whether the solution is worry beads or eating popcorn, we have difficulty sitting in silence with empty hands.

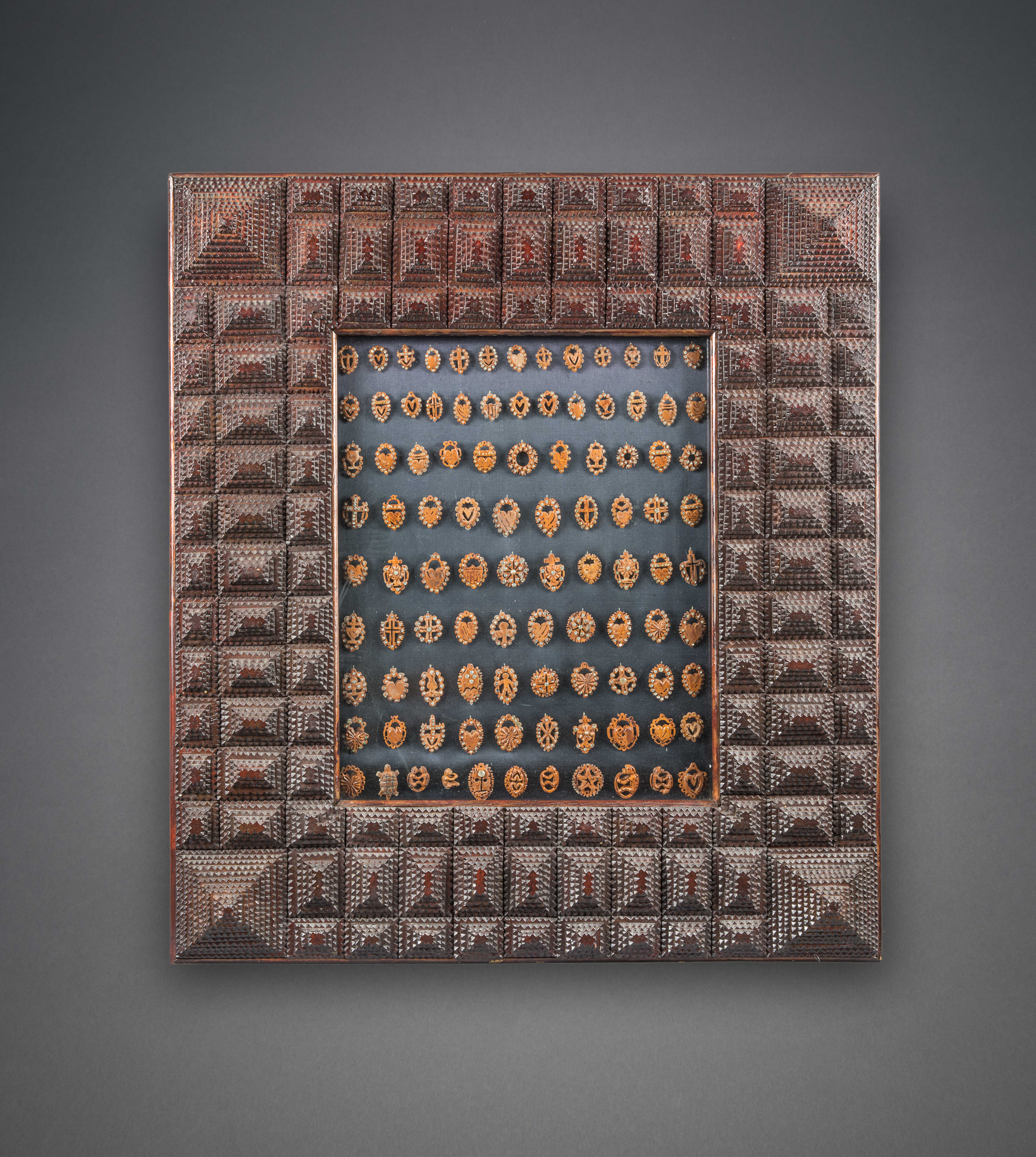

In a recent interview, the curator noted that the exhibition grew out of her initial survey of the institution’s holdings when she arrived at the Museum of International Folk Art about three years ago. As she explained, “In 2010, we had acquired a pretty substantial collection of tramp art. It was all religious pieces because that was the collecting interest of Eric Zafran, the man who formed it. Eric is a retired curator of European art, most recently he had worked at the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, Conn. We were eager to feature part of the great collection we had acquired, and I had an interest in tramp art, so it was a show waiting to happen.

“We have such rich collections that a lot of times our shows delve into the collections. That becomes our starting point. Simultaneously, as we are developing an exhibition, we are able to develop the collection as well. So I was acquiring pieces for the museum collection that broadened our holdings — some frames, some boxes, some household objects — things that would give people a more representative view of tramp art. I also set out to look at some of the strongest private collections of tramp art that I could, so I got a grant from our International Folk Art Foundation to make some trips and meet some collectors. About 35 percent of the show is our collection and about 65 percent comes from other collections.”

Tramp art birdcage, United States, late Nineteenth to early Twentieth Century. Courtesy of William F. Lassiter, Houston. —Paul Hester photo

The appellation “tramp art” has always been misleading, for most examples were not made in itinerant situations by homeless men. As she pursued the acquisitions, Addison paid special attention to examples signed by their makers: “That was one of my priorities in acquiring pieces for the collection. When and where we could, we knew the name of the maker, because I felt like — in order to demystify it — we needed to hit the reset button. Instead of making these speculations about who made tramp art, start with the biographies of those makers whose names we do know. That would allow us to determine if they came from Europe and were they immigrants or were they born in the United States? There are a lot of gray areas for tramp art. Were they working class, middle class or upper class? Where did they live? Who made it? When did they make it? Where were they? Was it rooted in any particular heritage? It seemed to me, the only way to do that was to begin with biographies and rebuild what we know about tramp art.”

She continued, “I found it wasn’t made by tramps, by and large, or at least that’s what we know from the biographies of the makers. There certainly were itinerants who did carvings. It seems to me from what I’ve observed and researched that itinerants tended to do things like whittling, ball and cage patterns, or chains, occasionally a piece in the tramp-art style that I define as dismantled scraps of wood that are notched and layered. What I’ve found from the biographies of most makers of tramp art is that they tended to be working class or middle-class men, and they had stable home lives.”

In her exploration of the subject, Addison has been aided by the catalog contributions of two other art historians with a connection to its multiple forms. Eric Zafran, the art historian and collector mentioned above, outlined his favorite part of the subject in “A Labor of Love: Religious Tramp Art.” Personal faith was the inspiration for many crosses, shrines and boxes in the tramp art style. The exhibition includes exceptional examples gathered by Zafran that are now in the museum’s permanent collection.

The intricate S-curve patterns of this frame dating to the late Nineteenth or early Twentieth Century are emphasized by varying paint tones. Damiani Family Collection.

Leslie Umberger, curator of folk and self-taught at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, addressed “Truth Inside the Myth: The Obscure History of Tramp Art in America.” In her previous position as a curator at the John Michael Kohler Arts Center in Sheboygan, Wis., she had come in contact with Adolph Vandertie (1911–2007), a whittler and self-described former hobo who had written about his experiences in Hobo & Tramp Art Carving: An Authentic American Folk Art Tradition. She noted in an interview, “I get really interested when I see one of the traditional carving styles taken in a personalized direction. Then it escapes the usual forms and becomes an individualized work of art. It is like being a magician — being able to impress somebody with what you can do.”

Discussing the exhibition’s organization, Laura Addison says, “One of the largest sections is called ‘Home and Nation’ — looking at the home as a microcosm of the nation and national values at the turn of the Twentieth Century and how central family was, because a lot of the exhibits are domestic household objects. And some of them are furniture, so the scale alone tells you that it was not made by an itinerant. A lot of them reflect a value of patriotism, and all of them reflect great craftsmanship and the value of industry, industry in the sense of hard work. And no ‘idle hands’ — that is how the show title came to be.

“Oftentimes — erroneously — people do not associate tramp art with craftsmanship. In this show, there are very humble pieces, but there are also pieces that are extraordinary in their attention to detail, their uniformity in the notching and really amazing design. They display clever problem solving and a beautiful sense of surface detail and form,” Addison noted.

The exhibition catalog No Idle Hands: The Myths & Meanings of Tramp Art is available for $50 through the online shop.

The Museum of International Folk Art is at 706 Camino Lejo. For more information, 505-476-1200 or www.moifa.org.

Journalist Karla Klein Albertson writes about decorative arts and design.