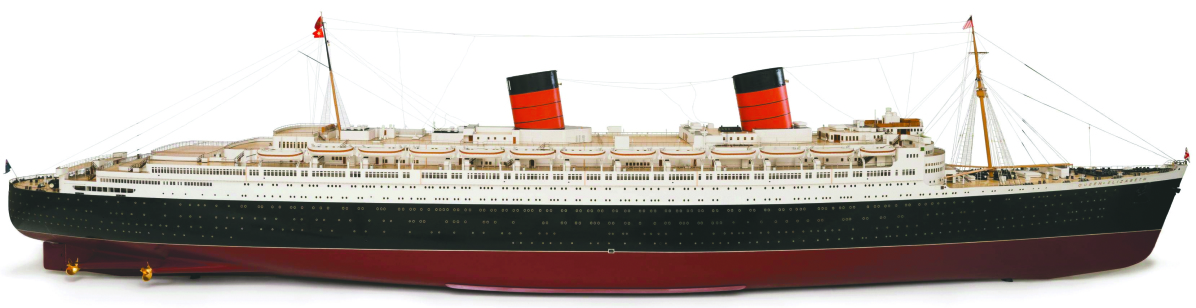

Curators describe this example as “the apex of ocean-liner exhibition models.” Its 22-foot-long hull is carved from a single log of African obeche and it took a team of five men 12 weeks to complete. Model of Queen Elizabeth by Bassett-Lowke Ltd, 1947–48. White mahogany, gunmetal, and brass. Peabody Essex Museum —Kathy Tarantola photo

By Jessica Skwire Routhier

SALEM, MASS. – In one sense, the great ocean liners of the late Nineteenth and early Twentieth Centuries were designed for a purely functional purpose: to carry large numbers of passengers safely and efficiently across the sea. In practice and over time, however, they were also meant transport them, while on board, into a closed and privileged world apart from the everyday. Ocean liners carried not only passengers, but also era-defining ideas about art and design, class and community, world and country. They were vehicles in both a literal and an ideological sense. “Ocean Liners: Glamour, Speed and Style,” at the Peabody Essex Museum (PEM) through October 9, examines the cultural complexity of the great age of ocean liners, from the mid-1800s through the postwar era.

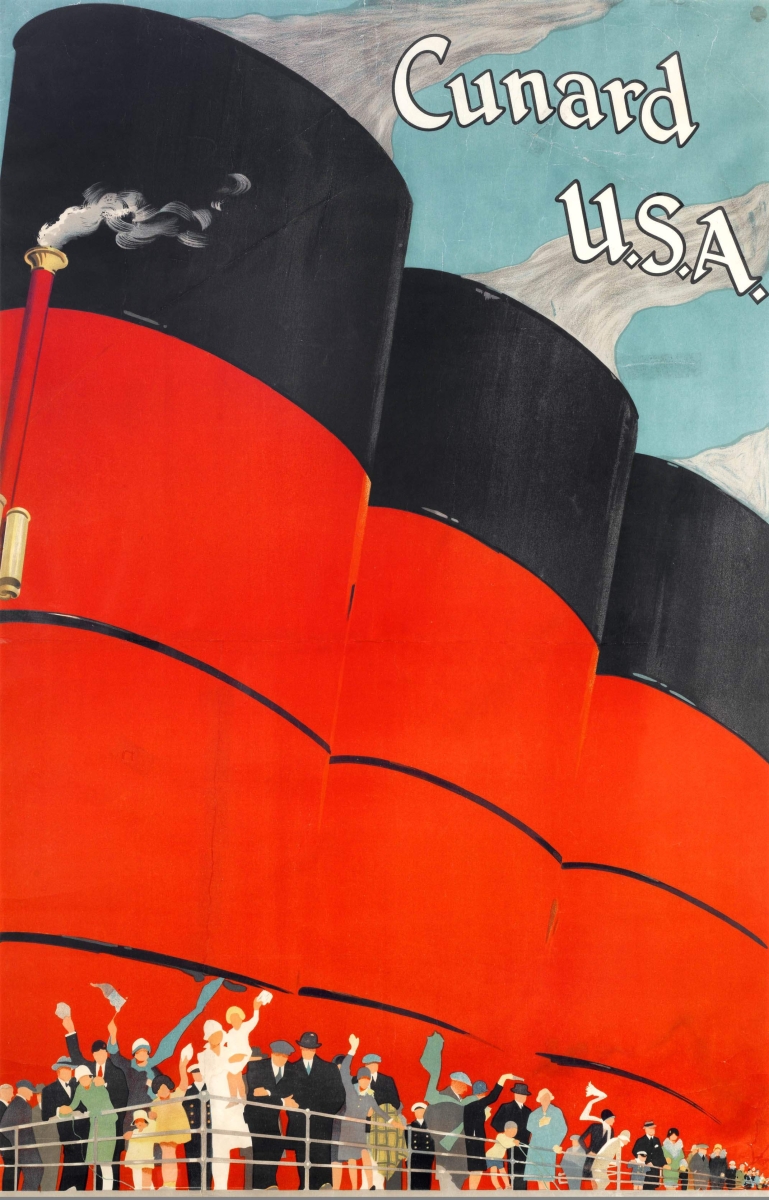

The show, which is co-organized by the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) in London and which will travel there in the fall, fits well with both organizations’ histories and collections. PEM was founded by sea captains and has been collecting materials related to ocean liners – wooden models, promotional posters and more – since at least 1870. The V&A, true to its mission, has long been acquiring and interpreting the material culture of ocean liners – furniture, wall coverings, schematic illustrations – as high expressions of international art and design. Along with the photographs and paintings that both documented and were inspired by ocean travel, all find a berth in PEM’s expansive and richly appointed exhibition.

Co-curators Daniel Finamore, of PEM, and Ghislaine Wood, of the V&A, set out to do “something that had never been done before,” which, according to Finamore, is “a comprehensive international investigation of ocean liner design across the board.” The distinction is a meaningful one, given that previous exhibitions on the topic have focused primarily on either the mechanics and technology of these leviathans of the deep – only one aspect of their design – or on the personal experiences of travelers.

“We’re in a transition moment now, I think it’s fair to say,” Finamore observes, “where the subject is becoming less associated with nostalgia of the people who traveled on board and more a subject of legitimate historical inquiry.” The striking promotional posters, the impressively huge wooden models – the one of the Queen Elizabeth, 1940, in the introductory gallery is fully 22 feet long – and the elegant luggage and fashions retain their important roles. Equally important now, however, are the ships’ carefully chosen and designed interiors, from intricately carved wood or stone panels to carefully coordinated suites of dinnerware.

One could argue that the heart of the exhibition is the series of three or four large galleries that show the evolution of ships’ décor over nearly a century, beginning in the 1870s. There is a sense of traveling through time as the visitor proceeds from the elaborately historicized finishes of Victorian and Edwardian ships – Arts and Crafts designer William De Morgan was a pioneer in this era – to the streamlined aesthetic of the 1920s and 1930s to the increasingly groovy vibe of post-World War II designs. It is not possible to ignore the way in which designers, globally, moved from an intimate, privileged and often nationally specific aesthetic – that of an English country home for British ships like Titanic, or of Bavarian castles for German ships like Kronzprinz Wilhelm – to concepts that were much more urban, international and modern.

A delight and a revelation in this section of the show is the series of chairs from different eras, from a bolted-down swivel chair from the turn of the last century to the overstuffed chintzes of the Normandie, 1934, and the Queen Mary, 1936, to the sexy polished wood and velour chairs designed by Gio Ponti and others for postwar Italian ships. Finamore says the achievements of these Italian designers were one of the surprises of the show for the curators. The catalog devotes a chapter to Ponti.

Also present is the orange and chrome creation by Robert Heritage for the Queen Elizabeth II, popularly called the QE2, which won a Design Council award in 1968. Then, too, there are the deck chairs, including one from Titanic, which evolved in design over time and even became inspiration for chairs that were never intended to be used aboard ship. Eileen Gray’s Transat chair, 1925-30, designed for a cháteau on the Riviera, illustrates that broad influence.

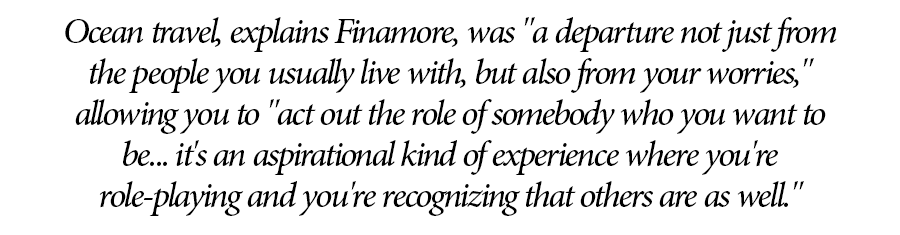

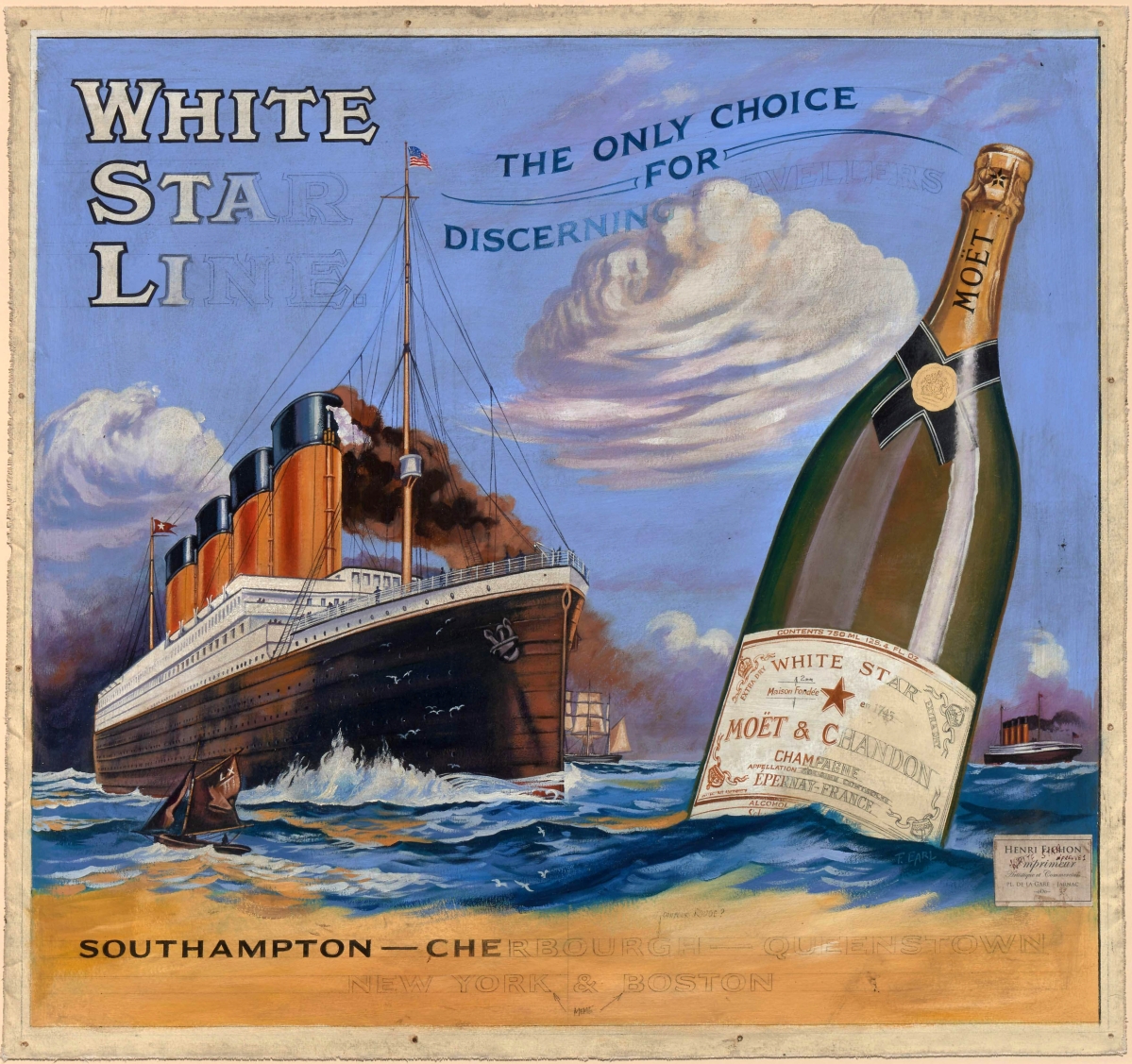

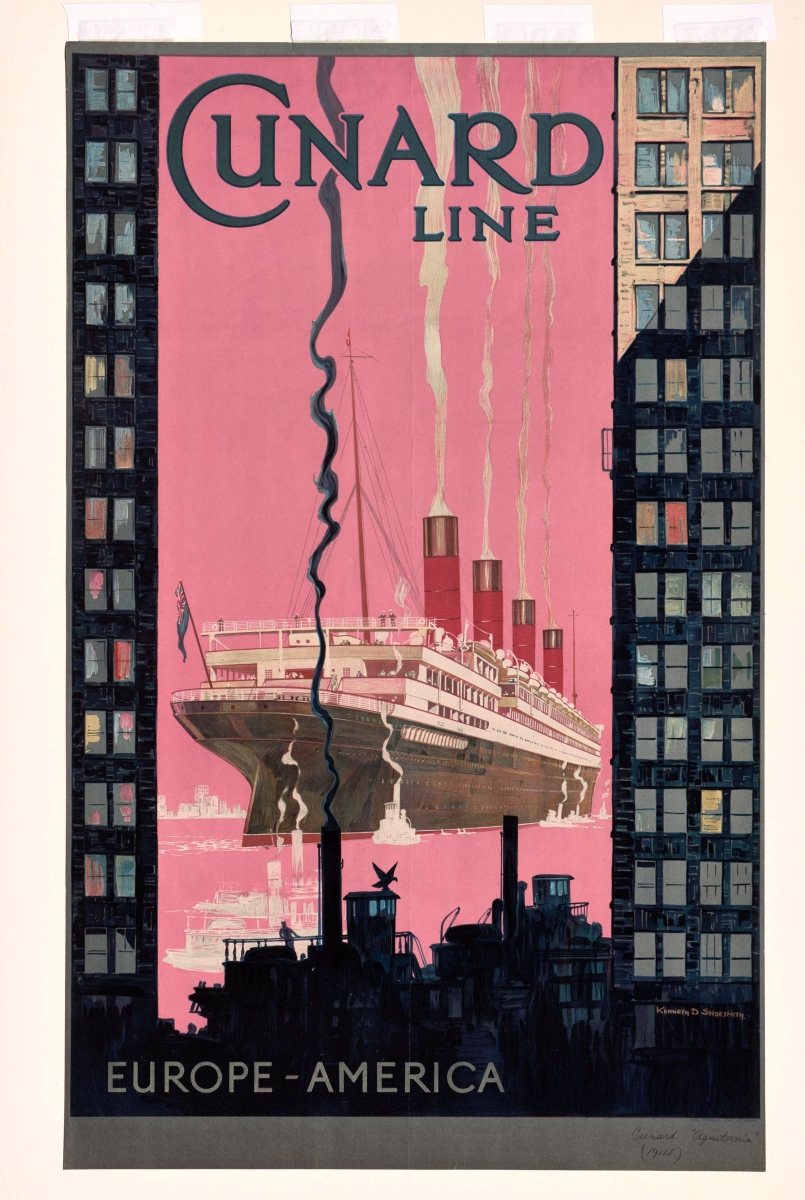

Ocean liners boasted to potential passengers that they could provide the most fashionable, elite and up-to-date experiences in everything from cabin furnishings to cuisine. As mechanical designs improved so that voyages were less rocky and engines quieter, and as hull designs developed to allow more spacious accommodations and communal areas, companies realized that they could promote not only speed and comfort, but also outright luxury.

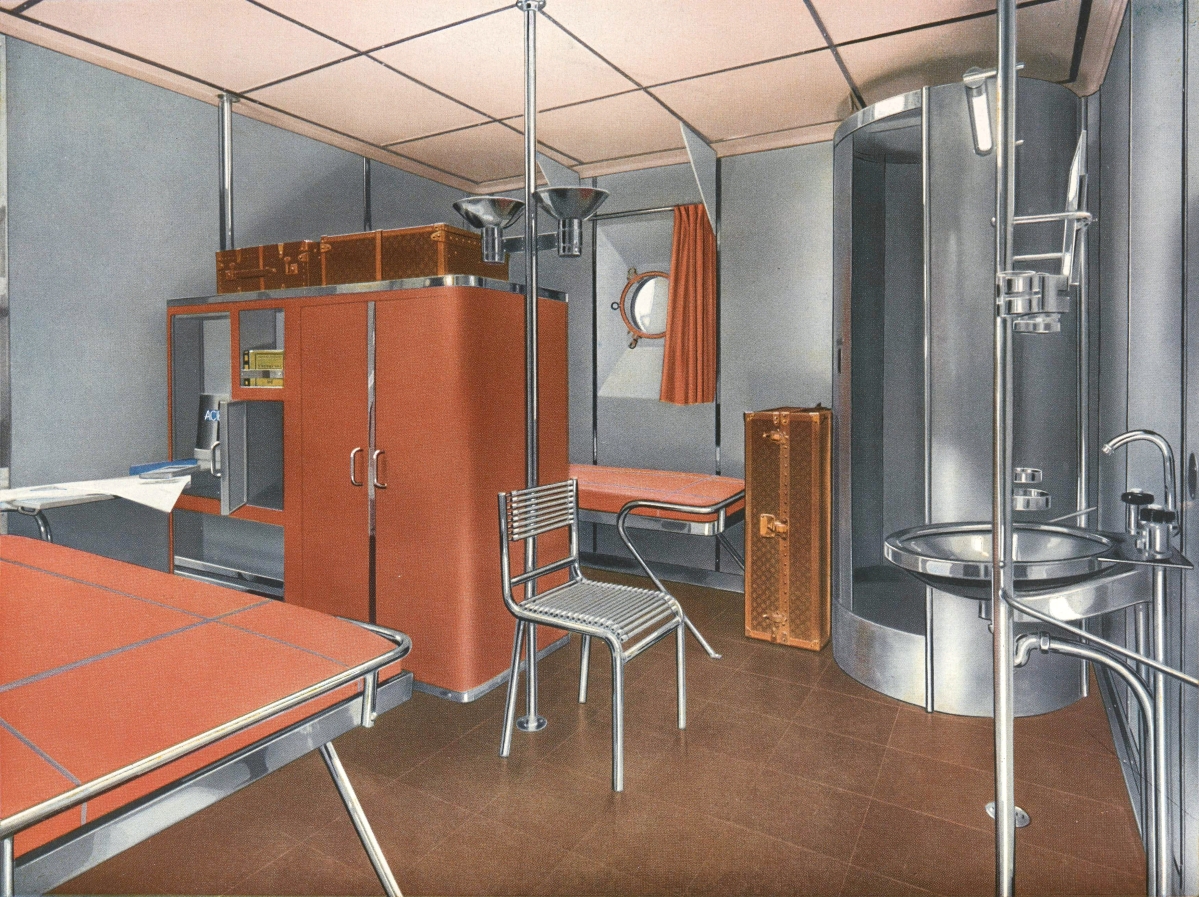

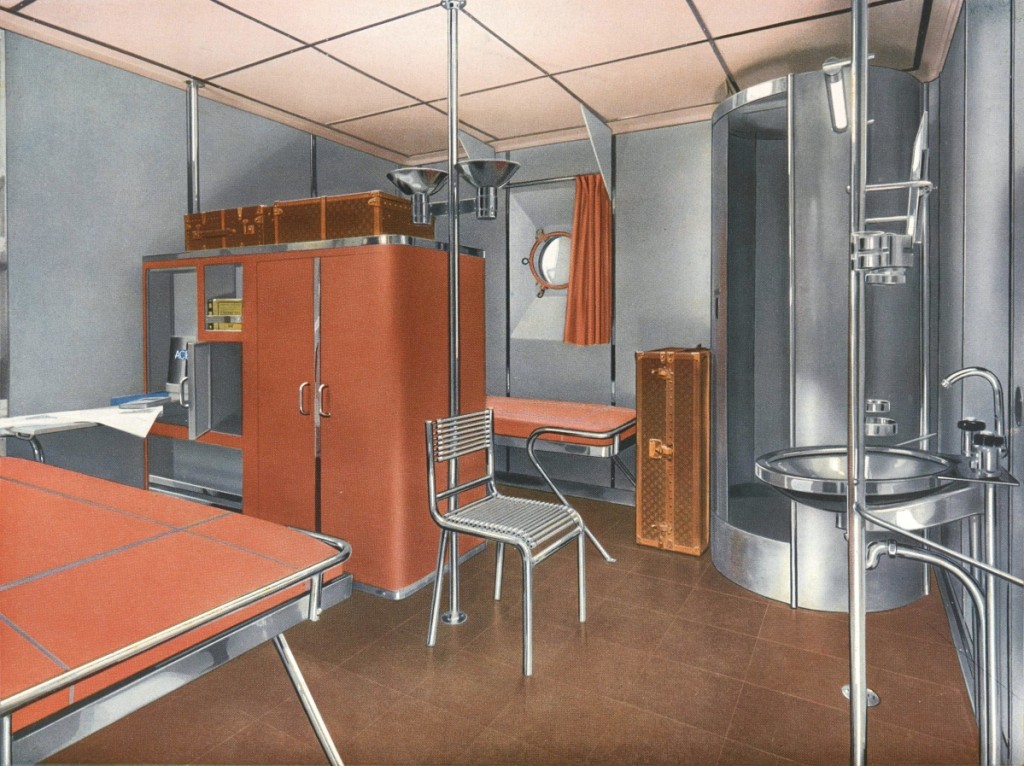

In 1934, French designer Rene Herbst organized a design competition for cabin furnishings made completely from stainless steel. Inventive though the designs were, they proved impractical because of the weight and structural limits of steel at the time. First-class steel cabin design by René Herbst, 1935. Phillips Library, Peabody Essex Museum. —Jarrod Staples photo

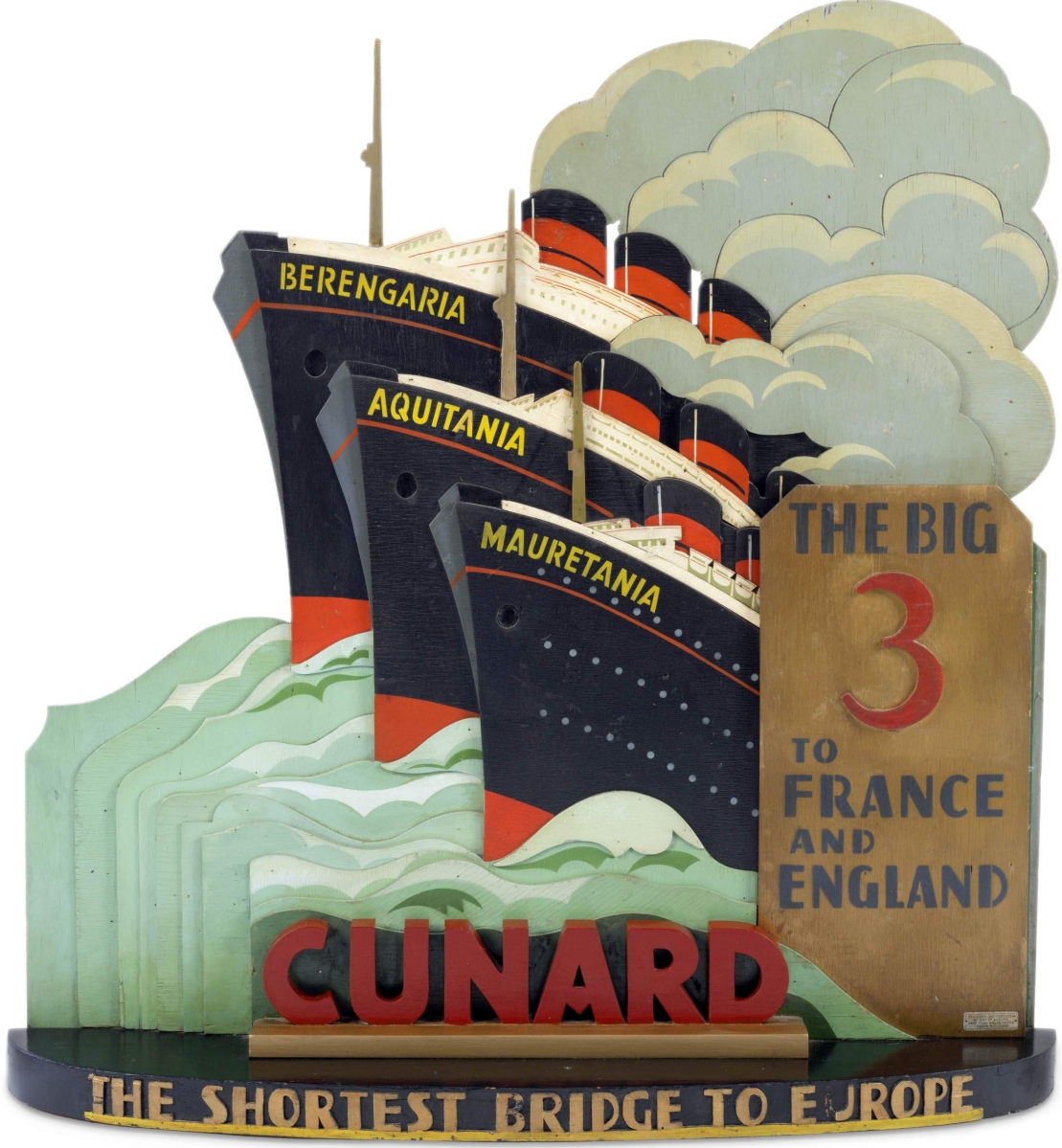

Ocean travel, explains Finamore, was “a departure not just from the people you usually live with, but also from your worries,” allowing you to “act out the role of somebody who you want to be… it’s an aspirational kind of experience where you’re role-playing and you’re recognizing that others are as well.” This idea is manifest in the way that ocean liners often “delivered the idealized version of the country you are heading to before you get there.” Passengers on the Normandie, for instance, could imagine they were “living in a swank Parisian apartment done up in the latest style,” take advantage of rarified shopping experiences and fashion shows, and enjoy what might be “the best meal that you’ve ever had in your life … better than the meals you were likely to get once you arrived.”

This luxury experience was at its “most extreme” for first-class travelers, says Finamore, but it was not exclusive to it. The phenomenon of emigrants traveling by ocean liner, well known in popular memory due to the Titanic tragedy, was primarily a Nineteenth Century one. Emigrants continued to travel by steamship in the 1900s, but, as time went on, less so on the large-scale passenger steamers known as ocean liners. Nevertheless, in the earlier days, liners reached out to potential emigrant passengers through the same strategies as moneyed clients. Promotional brochures and fliers describe the airy comfort of steerage cabins and the bounty of the food served. One third-class menu in the exhibition insists, in a firmly solicitous manner that recalls contemporary writer David Foster Wallace’s experience aboard a Caribbean cruise ship, that the management be made aware of any aspect of the food service that is unsatisfactory.

It was rare for promotional posters to make direct reference to emigrants – there is only one example in the show – but ships’ names like the Cincinnati or the Cleveland, both German liners, certainly played into emigrants’ aspirations for home and community on the other side of the Atlantic.

Finamore’s primary essay in the exhibition catalog discusses ocean liners as a sort of society in microcosm, even an idealized society. While ships were strictly divided by travel class, the classes themselves had a certain malleability. By the 1920s, former steerage cabins were being converted into a new budget class called “tourist,” and there was a growing sense that perfectly respectable passengers might choose whatever class best suited them for that particular voyage. That kind of mobility – along with the eagerness of ships to provide shared spaces for worship, child care, entertainment and exercise – appealed particularly to the upper- and middle-class Americans who made up much of Twentieth Century liners’ clientele.

Of course, the crew remained a world entirely apart, a world more often than not governed by its own hierarchy of race and ethnicity. Some prints and a rather remarkable large-scale oil of shipbuilders by the British artist Stanley Spencer put a face on such workers, albeit in generalized and somewhat romanticized ways. In the end, the underlying consciousness of the tragedies – told, in Finamore’s words, “through objects that evoke the story” – provides the necessary perspective.

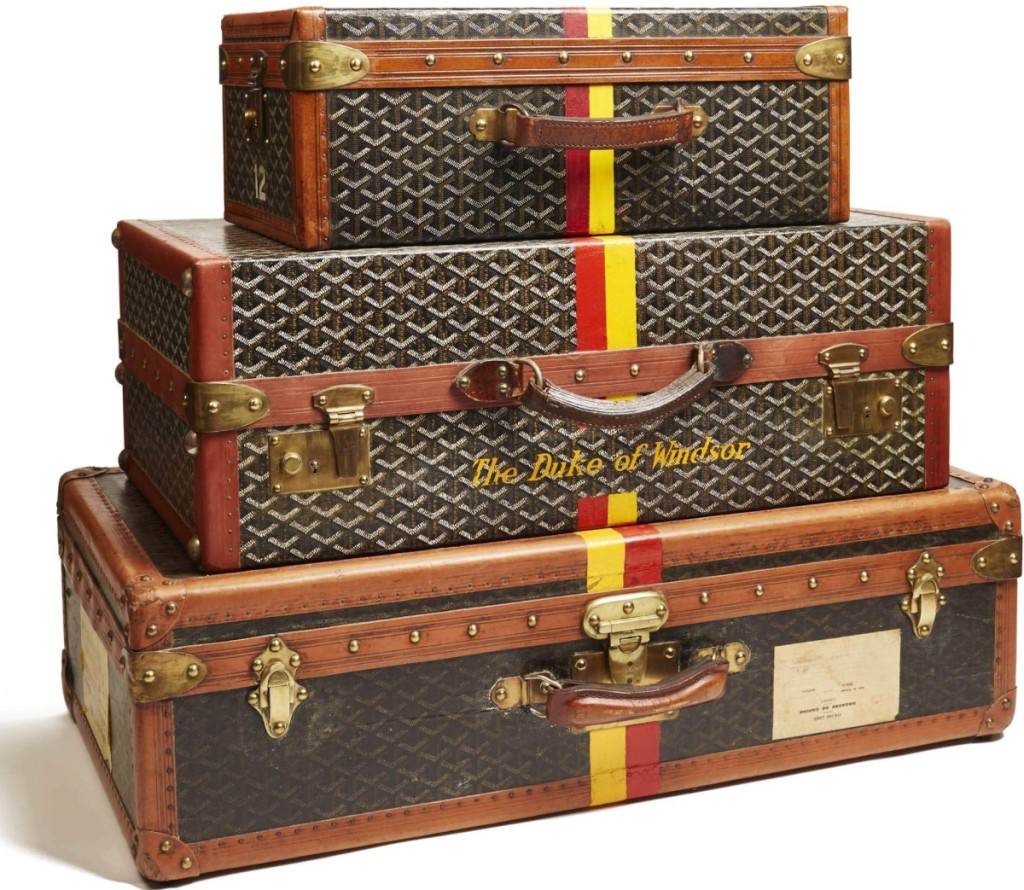

Fashion scholar Michelle Tolini Finamore writes that “a passenger’s luggage was an extension of his or her ensemble, and Louis Vuitton or Goyard trunks were immediate markers of socioeconomic status.” Luggage owned by the Duke and Duchess of Windsor by Maison Goyard, Paris, about 1940s. Coated and painted canvas, leather, brass and wood. Miottel Museum. —Luke Abiol photo

When seeing an 1892 chromo of the South Asian “Seedie Boys” who feed a great ship’s stokehole, for example, anyone who has read about Titanic‘s 1915 sinking or seen the movies will think of those trapped in Titanic‘s bowels as the tragedy’s first victims. Seeing in the same exhibition one of Titanic‘s deck chairs or the fragment of its first-class dining room, both fished out of the wreckage, is a powerful reminder that such class distinctions, in part, determined what and who was saved and is remembered today.

The enigma of what remains is a powerful part of the story that this exhibition tells. The prescience of museums like PEM, the V&A and others in salvaging and preserving the fabric of retired ships – not obviously a practical or cost-effective thing to do in any case – has ensured the survival of a material history. PEM, for instance, reportedly with one day’s notice, fetched the massive model of Queen Elizabeth from Cunard’s New York office lest it be disposed of. Museum staff revisited that heroic effort recently when, with great effort, they relocated the model from its permanent location on the first floor to the special-exhibition space on the second.

Furniture and paneling from German ships captured during wartime were ultimately preserved by the Mariners’ Museum in Newport News, Va., which also saw fit to save and store massive panels from the postwar SS United States, retired in 1969. Finamore says the exhibition as a whole “started to become a reality when I saw that large aluminum wall panel from the SS United States with crystals embedded in it that evoke stars.” The panel, along with the cut-glass panel from the ship’s ballroom, is once again properly backlit in the current exhibition, for the first time since the ship stopped sailing.

Visitors should nevertheless take care not to interpret the insistent presence of relics from the past to mean that the legacy of the great age of ocean liners has entirely come to a halt. The final galleries of the exhibition explore, convincingly, the legacy of the great ships in art, design and architecture up to the present day. Modernist photographers and Precisionist painters like Charles Sheeler and Charles Demuth drew intense inspiration from the curves and angles of ships’ machinery, advancing Modernist art in lasting ways. Artist-architect Le Corbusier designed buildings based on the streamlined aesthetic of ocean liners and generations of interior designers played with stainless steel, chrome, curves and inventive use of limited or narrowly defined space for everything from working-class homes to corporate offices.

These influences endure today, including in the design of the massive cruise ships that differ in important ways from, but are nevertheless the inheritors of, the great ocean liners of the past.

The exhibition is accompanied by a lavishly illustrated catalog from V&A Publishing in association with PEM, with essays by Finamore, Wood and others. Peabody Essex Museum is at 161 Essex Street. For further information, www.pem.org or 866-745-1876.

Jessica Skwire Routhier is a writer, editor and independent art historian. She lives in South Portland, Maine