Chasse with Christ in Majesty and the Lamb of God, French, circa 1180–90. Champlevé enamel, copper and wood core. Metropolitan Museum of Art, gift of J. Pierpont Morgan, 1917.

By Kristin Nord

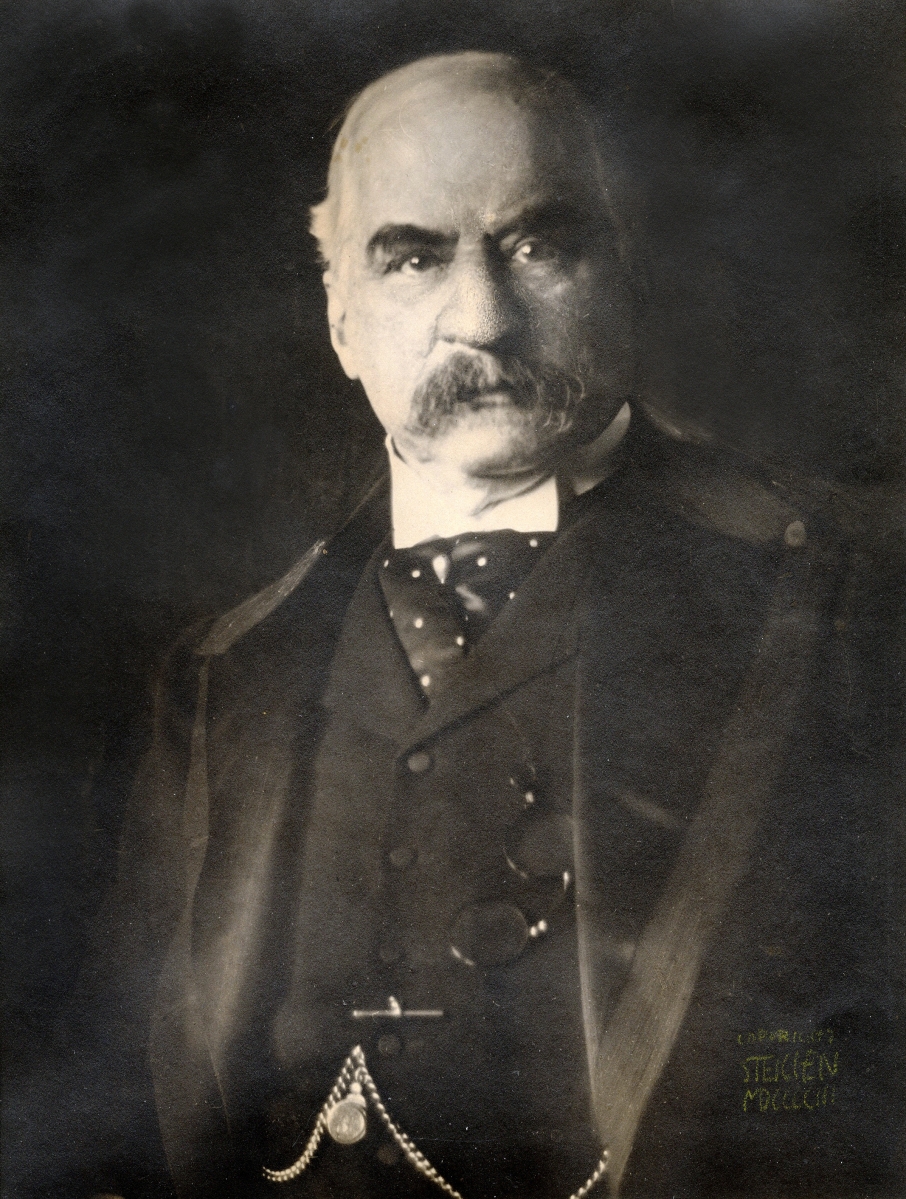

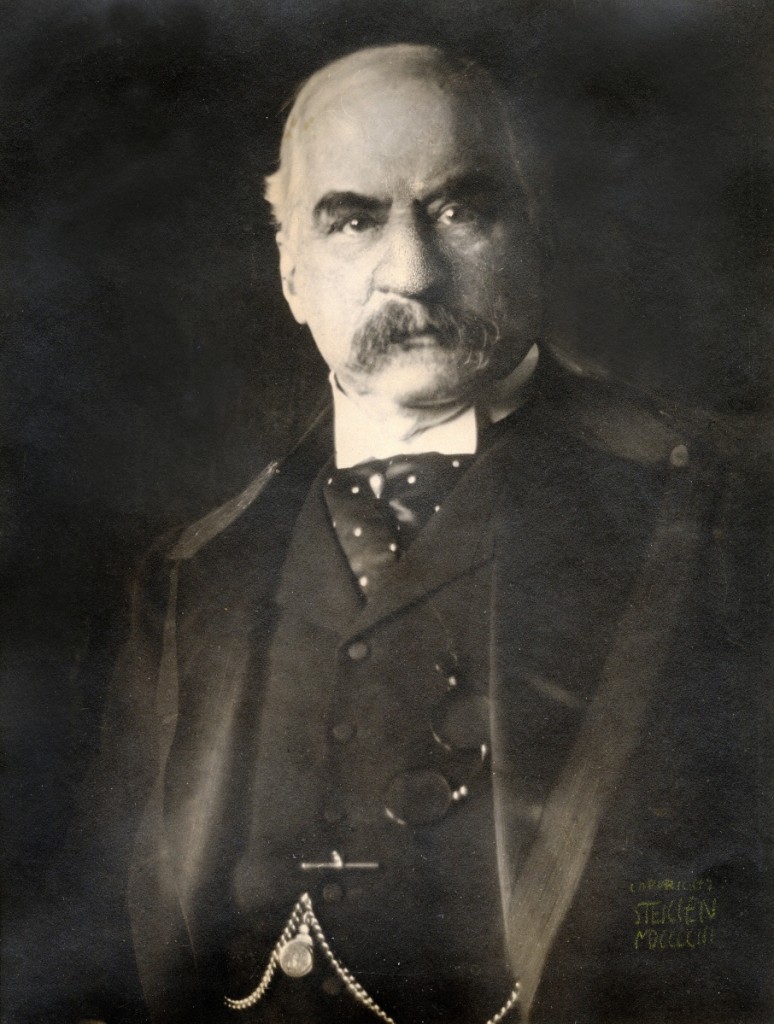

HARTFORD, CONN. – When John Pierpont Morgan (1837-1913), the great financier, inherited $15 million in 1890, his wealth freed him to embark on his life’s final chapter. The conditions were right for a man of his energies and organizational skills to build a world-class art collection. European aristocracy, long on ancestry but short on cash, was eager to trade with wealthy Americans, and the rise of scholarly connoisseurship and new techniques for authentication meant Morgan would have the means by which to document and validate his holdings.

“J. Pierpont Morgan, Esq.” by Edward J. Steichen, 1903, printed 1904. Gum bichromate over platinum print. Private Collection, courtesy Laurence Miller Gallery.

Ultimately Morgan’s acquisitions would form the foundation of superb collections at the Morgan Library, the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Wadsworth Atheneum. Because of the Morgan family’s deep Hartford roots, bequests upon his death also included more than 1,300 objects and $1.4 million for a Morgan Memorial Wing.

In “Morgan: Mind of the Collector,” at the Wadsworth Atheneum through December 31, viewers are introduced to the spoils of what amounted to one man’s full-on campaign. One hundred choice objects from the Wadsworth Atheneum’s permanent collections and significant works on loan make for a sumptuous sampler.

Linda H. Roth, senior curator and Charles C. and Eleanor Lamont Cunningham curator of decorative arts, first took on the inscrutable collector in a Wadsworth exhibition 30 years ago. The quality of his acquisitions, she said recently, have more than withstood the test of time. “They are exceptional – the objects are quite rare, and often are the best of their kind,” Roth said. She is once again at the helm of this exhibition, having worked with other Morgan scholars to prepare a vibrant feast.

In some ways, Morgan appears to have embarked on his project as a calling. As a lifelong Episcopalian, steeped in teachings from the King James Bible, Morgan also had a profound interest in the history and artifacts from biblical lands. While an object like the Twelfth Century gold chassé, or casket, could be savored for its beauty and its craftsmanship, Morgan viewed such works through a biblical lens. In this way a Fifteenth Century Flemish Book of Hours and a mid-Seventeenth Century bible, the first translated in a Native American language, also spoke to him, as did the triptych, “The Coronation of the Virgin,” on loan from the Met, considered to be one of the finest examples of Twelfth Century ivory carving from Gothic Cologne.

Wonderful archival photographs reproduced on large panels take viewers inside Morgan’s homes in both New York and London. The objects he chose to live with were often protected under glass domes or placed in large glass vitrines, and a number of rooms do feel a little like Selfridge-styled emporiums. Whether it is the exquisite miniature toy-sized gold “nécessaire” or an extraordinary ostrich egg ewer, bearing a Nuremberg hallmark of 1630 and functioning as sculpture and vessel, their invoices alone leave behind a paper trail for subsequent study.

The “Great Ruby” watch, watchmaker Nicolaus Rugendas the Younger, German, circa 1670. Case and dial: painted and raised enamel on gold, set with rubies; movement: gilded brass and partly blued steel. Metropolitan Museum of Art, gift of J. Pierpont Morgan, 1917.

Astonishingly, while Morgan regularly conferred with a constellation of scholars, dealers and collectors in his pursuits, he not only insisted on viewing all of the objects under consideration, but retained the final say in all purchases. At his death in 1913, he possessed some 20,000 objects, worth $60 million, or roughly the equivalent of $900 million today. Catalogs he commissioned, art in themselves, were prepared by leading scholars to document the provenance and authenticity of many objects.

Yet probing the inner life of the world’s greatest collector continues to elude scholars, and for good reason.

“Neither introspective nor articulate,” writes Jean Strouse, author of Morgan: Financier, “he was, as Henry Adams said of Theodore Roosevelt, ‘pure act.’ He never said anything to explain what he did in the financial world, left very few reflections on his collecting and posted ‘no trespassing’ signs all over the place.” Then he burned “hundreds of letters he had written to his father twice a week, every week, for 30 years.”

At the end of his life Morgan was reeling psychologically, wearied by Congressional hearings that had challenged his motives as a financier and the target of a muckraking press that had reduced him to caricature. An avowed workaholic who claimed he could accomplish in nine months what others did in a year, he was now unable to function. Although he was being treated for a serious clinical depression, he was not improving. He died after a massive stroke in March, just a few months after he testified.

“Having assembled his collections with an extravagant passion for 20 years, he made no explicit provision for their future: beyond the vague injunction to his son (whom he did not even like) about making them available to the American people, he simply opened his hands and let them go,” Strouse notes.

“The Nativity (Christmas Day),” page from a Gradual, illuminated by Silvestro dei Gherarducci, Italian, 1392–99. Vellum. Morgan Library and Museum, purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan in 1909.

Jack Morgan would exhibit his father’s holdings at the Met in 1914, the only time they were shown together. Then he moved swiftly to sell off works, indeed, significant collections, to meet bequests and pay estate taxes. Other serious collectors, notably Henry Clay Frick, were happy to snap up choice items from Morgan’s estate, including the Fragonard Room, a showpiece of Morgan’s Prince’s Gate residence. Even today it is rather a shock to discover that so many of the memorable items – whether French furniture, clocks, enamels or the dozens of Renaissance bronzes at the Frick Collection – came to the institution by way of Morgan.

“I confess to feeling comically proprietary about these objects” Morgan’s biographer Strouse writes, and it is hard not to share her sentiment. “I want everyone to know they were Morgan’s before they were Frick’s, but Morgan himself apparently did not.”

And so, for those of us viewing the exquisite shards of his collecting life – the rare Morgan cup ultimately traced to the Roman Empire, on loan from the Corning Museum of Glass; or the elaborate majolica vase, acquired from the Fredèric Spitzer collection and decorated with Raphaelesque grotesques, birds, sea monsters, satyrs, sphinxes and medallions, we are left with often-breathtaking objects to contemplate and with questions.

“Many viewed him as a man with gargantuan appetite for money and for power, which he would do anything to satisfy,” Roth writes, in “J. Pierpont Morgan, Collector,” an essay published in a catalog of the same name. Yet the distance of a century suggests a contemporary portrait would be far more nuanced.

“He was not a populist, but he was fiercely patriotic, even though he spent half his life overseas,” she continues. “Undoubtedly, he believed that American culture should rise to a level worthy of its political and economic stature and that, as in business, he had the ability to contribute toward this end.”

The Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art is at 600 Main Street. For information, www.thewadsworth.org or 860-278-2670.