The Huntington Museum of Art in Huntington, W.Va., acquired this three-piece sugar and tea caddy set in the tea-pickers pattern by Huguenot-trained Royal goldsmith Thomas Heming (1722–1801), who made the set in 1757. It belonged to Queen Elizabeth II and, more recently, the American bibliophile Robert Pirie (1934–2015). —John Spurlock photo

By Daniel Grant

Regularly, as they look back on a year gone by, museum directors want their institutions to be thought of for the exhibitions they put on, the number of visitors who came to see those exhibits and the amount of money it all brought in. Perhaps as we recall what stood out in 2017, what comes most to mind is fewer individual exhibitions but a single issue: what museums are permitted to do with the objects in their possession. Should they take them down if certain groups find them offensive? There has been more talk about this than about anything else.

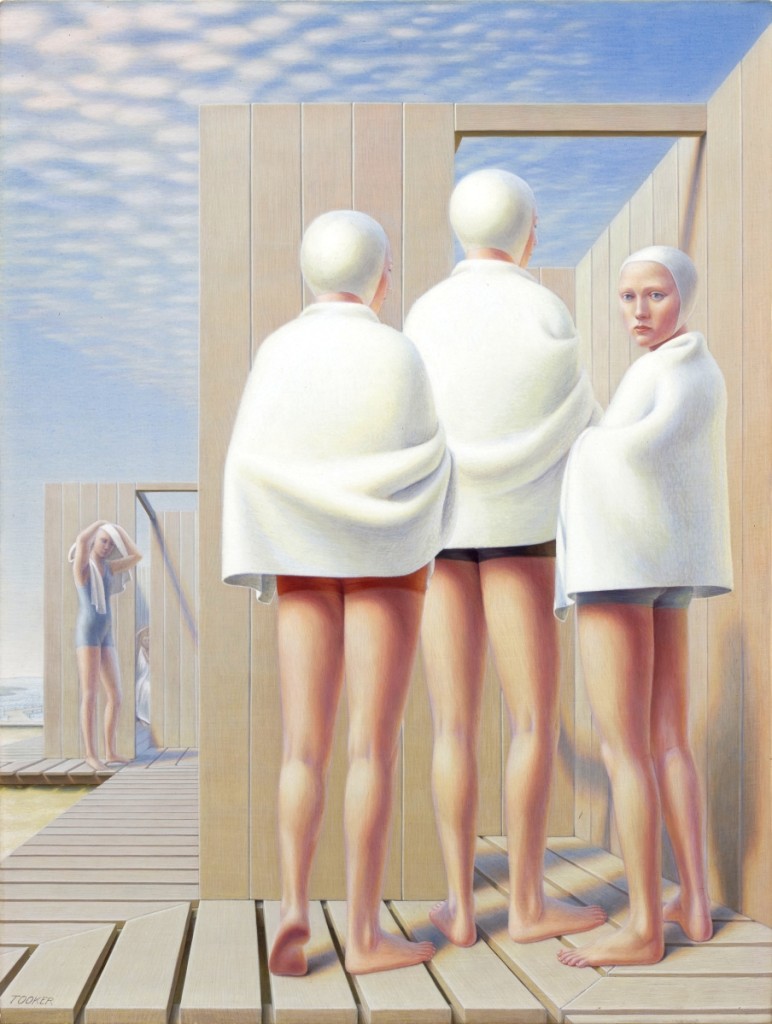

“Bathers (Bath Houses)” by George Tooker (1920–2011), 1950. Egg tempera on gessoed board. The Huntington Library, Art Collections and Botanical Gardens

Calls to remove Dana Schultz’s painting “Open Casket” – a semiabstract take on black lynching victim Emmett Till’s 1955 funeral by a white artist – at the Whitney Biennial were not heeded by the museum. However, many visitors had a difficult time viewing the work. Activists crowded around the picture to block access to it. The Whitney again faced criticism from Native American groups for exhibiting the work of Jimmie Durham. The artist, whose work references American Indian imagery, claims Cherokee heritage but cannot prove it.

Activists had more success at both the Guggenheim Museum and the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis. At the Guggenheim, an installation and two videos that portrayed animal cruelty that had been included in an exhibition of current Chinese art were removed after museum officials expressed fear that animal rights activists would cause damage to the artwork or the museum or both. At the Walker Art Center, an outdoor sculpture by Los Angeles artist Sam Durant titled “Scaffold” decrying capital punishment was removed from museum grounds after members of the Dakota Native American tribe complained that it was a painful reminder of the largest mass execution in US history, in which 38 Dakota Indians were hanged in 1862 in nearby Mankato, Minn. That work was ritually buried by tribesmen.

Moving a step away from high art to illustration, the Dr Seuss Museum chose to paint out an offending Chinese figure, which had been part of the author’s first children’s book – And to Think that I Saw It on Mulberry Street, published in 1937 – in the face of a looming threat of a boycott.

Freedom of expression, even what some see as offensive expression, requires champions. The Whitney showed some spine, not so much the other museums. Perhaps one might also give a shout-out to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, petitioned to remove a 1938 painting in its permanent collection, “Therese Dreaming” by Balthus. The work shows a prepubescent girl lounging in such a way as to provide a crotch shot (she wears underpants). The Met wisely declined.

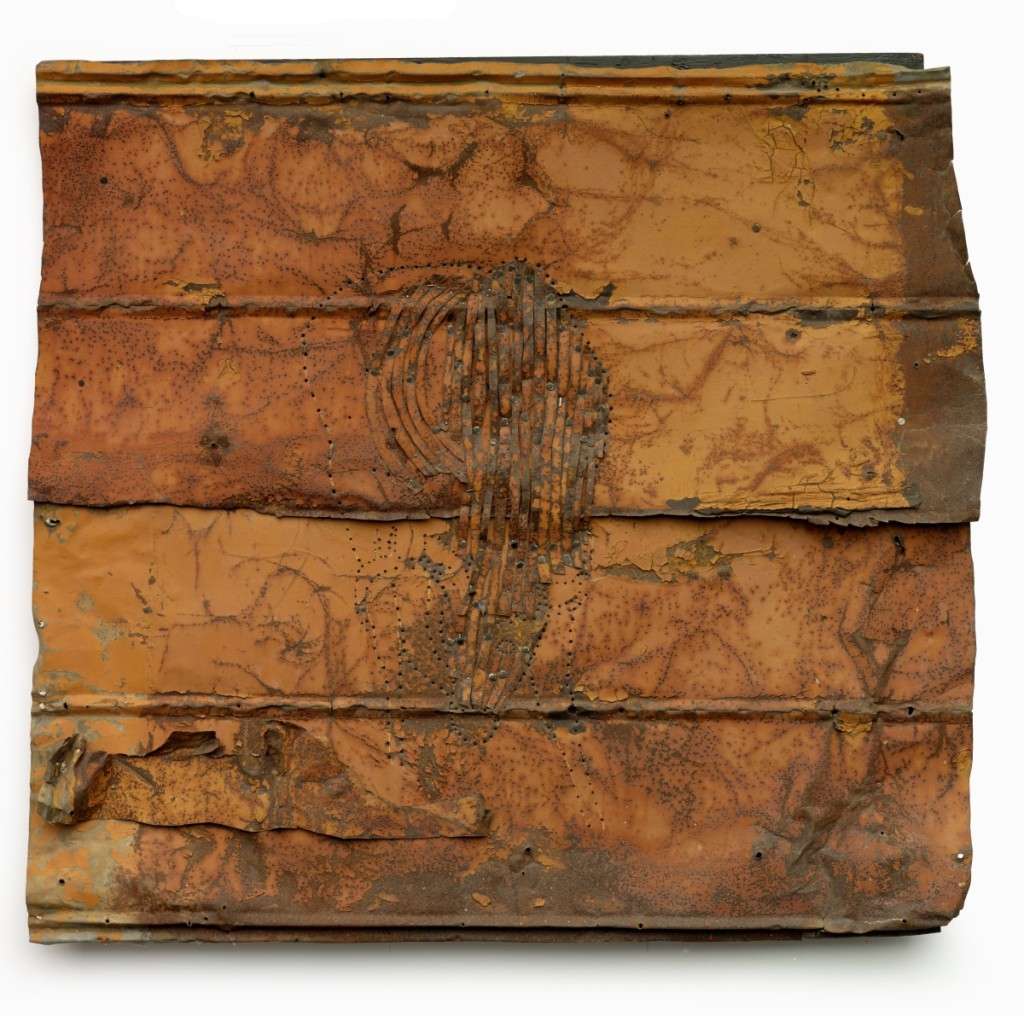

“Shack Town” by Thornton Dial (1928–2016), 2000. ©Estate of Thornton Dial. New Orleans Museum of Art. —Stephen Pitkin/Pitkin Studio photo

The largest controversy involved the Berkshire Museum in Pittsfield, Mass., which sought to sell a group of its most prominent artworks – including prized pieces by Norman Rockwell, Frederic Church, Albert Bierstadt and Alexander Calder – to augment the institution’s endowment and refocus the museum’s basic mission. Does a museum have a right to sell its most notable artworks, and to do it for some other reason than to raise money to buy more artworks? The court of public opinion and the court of law have been weighing in on those questions.

In other museum news, the Metropolitan Museum reported the most visitors ever – seven million – but found itself dealing with a $40 million deficit, causing the institution to delay the building of a new $600 million wing. The financial news was not helped by reports that top administrators at the Met were given substantial pay increases and that the director, Thomas Campbell, had what was described as an “inappropriate relationship” with a member of the museum’s digital staff. Campbell was pushed out in February.

There has been, of course, more positive news at the nation’s major museums, including the acquisition of new artworks and other objects for their permanent collections. Banker David Rockefeller, who died in March at 97, was a renowned collector of art. Much of his 15,000-work collection will go to the Museum of Modern Art, which his mother helped found in 1929. Other institutions also are receiving specific pieces as part of his bequest, such as Maurice de Vlaminck’s “Paysage de Banlieu” (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston), Camille Pissarro’s “Landscape Near Pontoise” (National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC), Andrew Wyeth’s “River Cove” (Portland Museum of Art, in Maine), Edouard Manet’s “La Brioche” (Metropolitan Museum of Art) and Martin Schongauer’s “Death of the Virgin” (Morgan Library & Museum).

“Drought” by Ronald Lockett (1965–1998), 1994. ©Estate of Ronald Lockett. New Orleans Museum of Art. —Stephen Pitkin/Pitkin Studio photo

The Whitney Museum was given a 1932 Edward Hopper painting (“City Roofs”) by an anonymous donor, as well as a wealth of archival materials relating to the artist from the Arthayer R. Sanborn Hopper Collection Trust. The painting depicts the rooftop of Hopper’s Greenwich Village studio, which he maintained for more than 50 years. A bit uptown, the Morgan Library added a drawing by Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot (“Seated Camaldolese Monk,” 1834, gift of Jill Newhouse), as well as others by David Hockney (“Celia, Paris,” 1969) and Martin Puryear (“Drawing for Untitled,” 1990), both of which were acquired through purchase funds. The Hockney portrait is of Celia Birtwell, a British fabric designer and frequent subject of the artist’s drawings and paintings.

On occasion, the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles receives items as gifts – Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser donated 386 works by 17 different photographers, including Berenice Abbott, Imogen Cunningham, William Eggleston, Andreas Feininger and Dorothea Lange – but this well-endowed institution tends to be a buyer.

In the past year, it purchased 16 drawings by such artists as Michelangelo, Lorenzo di Credi, Andrea del Sarto, Parmigianino, Rubens, Barocci, Goya and Degas, as well as a 1721 painting by Jean Antoine Watteau (“The Surprise”) and Parmigianino’s circa 1535 “The Virgin and Child with Saint Mary Magdalen and the Infant Saint John the Baptist.” The Parmigianino had been in England for almost 250 years. The Getty bought it in 2016 for £24.5 million from the Dent-Brocklehurst family of Sudeley Castle, Gloucestershire. However, an export license was not granted for eight months while the British government sought institutional buyers to match the price. No British museums, however, made a bid and the painting was deemed free to go.

Sometimes, an object donation may be just one item while other times it may be a group. That group, if sufficiently sought-after and valuable, may come with conditions, such as the artworks cannot be sold or must be on display all the time or must be exhibited together – or something. A donation of 113 Dutch and Flemish Golden Age works by 76 artists (including Rembrandt, Rubens, Gerrit Dou, Frans Hals, Albert Cuyp and Jan Steen) from collectors Rose-Marie and Eijk van Otterloo and Susan and Matthew Weatherbie to Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts came with the promise that 85 percent of the collection will always be on view and that the museum will create a Center for Netherlandish Art. That center is scheduled to be opened in 2020.

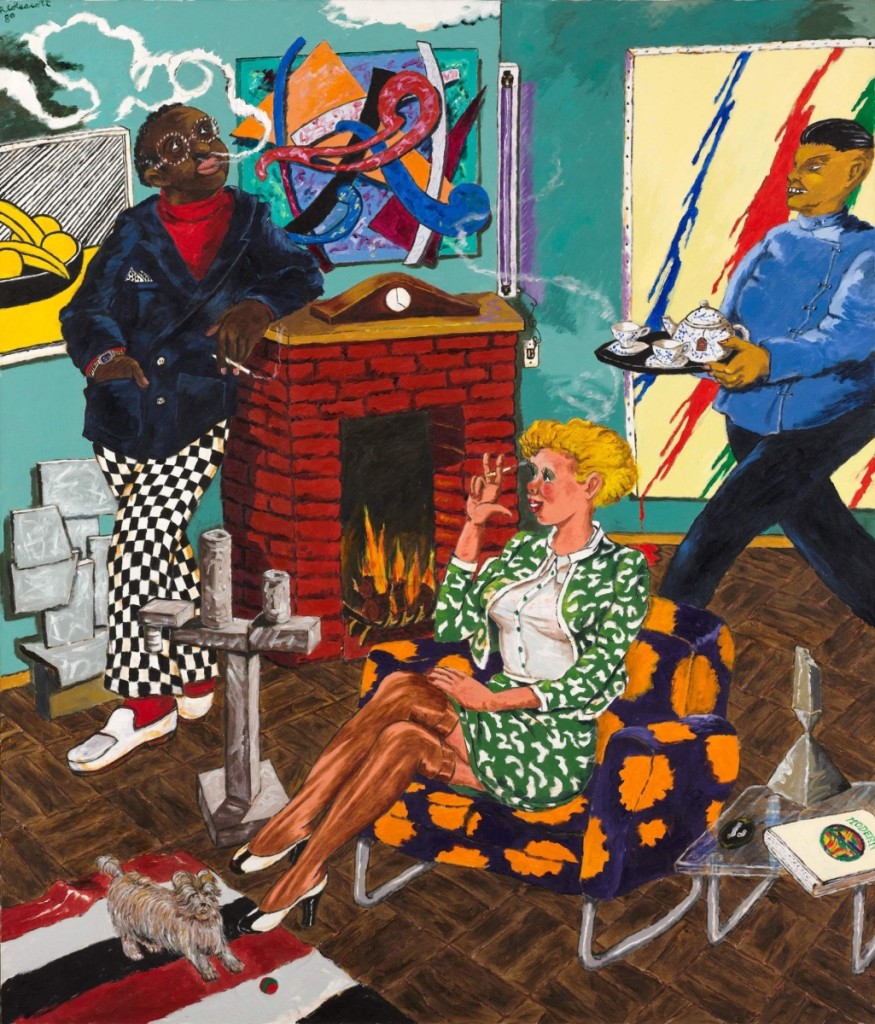

One of the areas in which museums have sought to expand their permanent collections is African American art, and in the past year the Cleveland Museum of Art purchased Norman Lewis’s 1960s abstract painting “Alabama” and was given, by Agnes Gund, Robert Colescott’s 1980 “Tea for Two (The Collector).” Colescott’s highly colorful painting plays off stereotypes, with an African American art collector leaning in a jaunty manner against a fireplace while he and a woman with blonde hair are being waited on by a butler carrying a tray with service for two.

On a similar note, the High Museum in Atlanta purchased Kara Walker’s 58-foot-long cut-paper silhouette

“Tea for Two (The Collector)” by Robert Colescott (1925–2009), 1980. Acrylic on canvas. Cleveland Museum of Art

installation of 2015, “The Jubilant Martyrs of Obsolescence and Ruin.” The New Orleans Museum of Art increased the number of works by African American artists in its permanent collection with the acquisition of ten works from the Souls Grown Deep Foundation, a nonprofit organization that since 2010 has aimed to expand the appreciation of largely unrecognized black artists in the Southeast. The acquisition includes two works by painter Thornton Dial, paintings and assemblages by Ronald Lockett, Joe Minter and Mary Proctor, as well as five quilts created by the women of Gee’s Bend in Alabama.

For its part, the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City has sought to increase its holdings in photography, which resulted in the acquisition of 800 photographs – by such American and European artists as Nadar, Gustave Le Gray, Edward Steichen, Jaromir Funke, Claude Cahun, Alfred Eisenstadt, Dorothea Lange, W. Eugene Smith, Robert Frank and Diane Arbus – through a $10 million award from the Hall Family Foundation, a private philanthropic organization active in the Kansas City area since 1943.

Most of the time, museums gain possession of art through gifts, bequests and purchases, but occasionally the courts decide what can stay and what must go, especially when objects that may have been looted are involved. The Boston Museum of Fine Arts reached an out-of-court settlement with the estate of Emma Budge, allowing the institution to keep seven pieces of Eighteenth Century German porcelain that were sold under Nazi duress in Berlin in 1937. The Boston Public Library, however, was required to return to the Italian government two illustrated religious manuscripts dating to the Fifteenth century that had been stolen from their owners in Sicily. The Metropolitan Museum of Art also sent back to the Italian government a 2,300-year-old Greco Roman vase that had been looted from a tomb in Italy in the 1970s.

Daniel Grant is the author of The Business of Being an Artist , published by Allworth Press.

.jpg)

.jpg)