Even though designers associated with the Wiener Werkstätte tended to avoid Western historicism, some of Hoffmann’s work illustrates his interest in classicism. Centerpiece designed by Josef Hoffmann and executed by Wiener Werkstätte, 1924. Brass. Minneapolis Institute of Art.

By Kate Eagen Johnson

NEW YORK CITY – “It was the power of working together and how this dedicated group of artists, craftsmen and patrons collaborated to create some of the most beautiful and luxurious objects of the early Twentieth Century that spoke to me as a curator and a connoisseur.” Janis Staggs pinpointed what moved her most deeply about “Wiener Werkstätte 1903-1932: The Luxury of Beauty,” the resplendent exhibition dazzling visitors at the Neue Galerie New York until January 29. Staggs, director of curatorial and manager of publications, and Dr Christian Witt-Dörring, curator of decorative arts, have co-curated the first major retrospective of the Wiener Werkstätte in the United States. The pair have also co-edited the magnificent catalog to which they contributed essays.

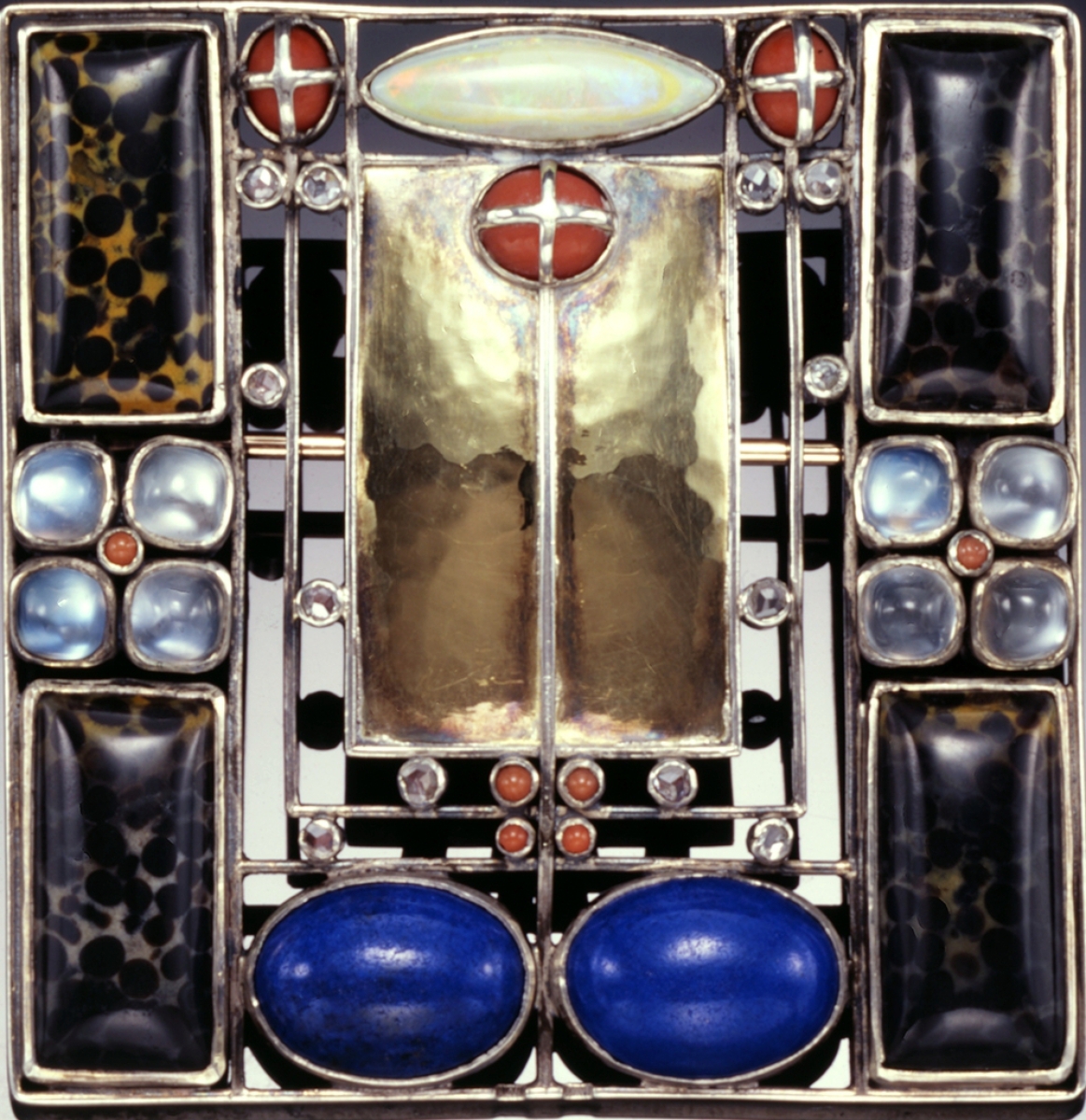

Staggs told in conversation how Neue Galerie board members recognized the value of an ambitious exhibition, and the first in an American museum, which would show the variety of the firm’s output and give credit to the vast range of designers who were part of the firm’s 30-year history. She emphasized that many of the decorative arts objects on display have never been shown in this country before and may never appear here again. It is clear that the Neue’s special relationships with collectors, scholars and museum personnel across Europe and the United States have made this once-in-a-lifetime exhibition possible. The display contains myriad Wiener Werkstätte classics among the 400 examples of furniture, ceramics, glass, metals, jewelry, textiles, fashion, graphics, wallpaper, painting and photography on view.

Generally translated as Vienna Workshops, the Wiener Werkstätte was founded by the architect and designer Josef Hoffmann (1870-1956), the artist and designer Koloman Moser (1868-1918) and art patron and financier Fritz Waerndorfer (1868-1939) in 1903. The many talents drawn to this Arts and Crafts “beehive” akin to a makerspace of today included Dagobert Peche (1887-1923), Carl Otto Czeschka (1878-1960), Michael Powolny (1871-1954), Vally Wieselthier (1895-1945) and Eduard Josef Wimmer-Wisgrill (1882-1961).

Among the underlying beliefs driving the artists’ cooperative were the importance of a unified approach to art and design across media that gave predominance to the “total environment” ideal of Gesamtkunstwerk; the need to look beyond clichéd historical revivals for style inspiration; and the centrality of providing artists and artisans the freedom to create imaginative, finely crafted items in whatever media they chose. These objets d’art, produced at the organization’s own workshops or at other manufactories per designers’ specifications, were sold primarily through Wiener Werkstätte retail outlets in select European cities. The artistic aims of the Wiener Werkstätte remained high, with the implementation of large-scale commissions a particular focus, even as attendant financial realities proved a constant source of worry and struggle.

Among the underlying beliefs driving the artists’ cooperative were the importance of a unified approach to art and design across media that gave predominance to the “total environment” ideal of Gesamtkunstwerk; the need to look beyond clichéd historical revivals for style inspiration; and the centrality of providing artists and artisans the freedom to create imaginative, finely crafted items in whatever media they chose. These objets d’art, produced at the organization’s own workshops or at other manufactories per designers’ specifications, were sold primarily through Wiener Werkstätte retail outlets in select European cities. The artistic aims of the Wiener Werkstätte remained high, with the implementation of large-scale commissions a particular focus, even as attendant financial realities proved a constant source of worry and struggle.

One of the attributes Staggs found the most surprising was the relative longevity of the design company. “It was a miracle that the Wiener Werkstätte survived for 30 years,” stated the co-curator. She described the vision and determination of Josef Hoffmann and how he was able to attract a series of financial underwriters who believed in the Wiener Werkstätte. “When one person backing it lost money there would be someone else who would step up and say, ‘I will support the Wiener Werkstätte.'” Even though managers paid close attention to corporate branding, and made shifts in materials and product lines in response to pecuniary pressures, the business closed in 1932.

The co-curators chart the firm’s story and evolution in aesthetics over three decades. Staggs spelled out how the primary galleries of the exhibition were designed to evoke display settings of the era. “One room is an homage to the first Wiener Werkstätte exhibition, which was held in Berlin in 1904. The second gallery acknowledges Josef Hoffmann’s simultaneous work as an architect and his turn toward a form of Neoclassicism in the 1910s. The final main gallery was inspired by Hoffmann’s design for the Wiener Werkstätte room in the Austrian Pavilion at the Paris 1925 Art Deco exhibition.”

The “Founding Years, 1903–05” gallery highlights the earliest works designed by Josef Hoffmann and Koloman Moser and fabricated by the Wiener Werkstätte. —Hulya Kolabas photo

Of particular interest to an American audience is the captivating tale of Joseph Urban (1872-1933) and the Wiener Werkstätte’s satellite salesroom in New York City, an aspect explored through a spotlight gallery and two catalog essays authored by Staggs. Born in Vienna and trained as an architect at the Akademie der bildenden Kunste (Academy of Fine Arts), Urban immigrated to the United States in 1911 to work as art director at the Boston Opera Company. In 1914, he moved to New York where he provided similar services for the Metropolitan Opera Company and the Ziegfeld Follies. Through the latter Urban met William Randolph Hearst who, in turn, hired this master of stagecraft as artistic director of his film studio Cosmopolitan Productions, an arrangement that existed from 1920 to 1925.

During a return trip to Vienna in 1921, Urban became enamored with the idea of promoting the design principles of the Wiener Werkstätte in the United States. He initially considered producing a limited-edition arts publication with Vienna Secessionist artist Gustav Klimt as an introductory subject, but then never progressed beyond the development phase. Instead, he turned his energies toward launching a New York branch of the firm. He financed, designed, stocked and ran the shop with the assistance of his wife, Mary, and sister-in-law Anne Moore. (As Staggs notes in the catalog, the New York store was actually named the “Wiener Werkstaette of America,” a tweak which may have been made to counter residual Austro German prejudice in the era after World War I.) Opening in 1922, the enterprise existed for roughly a year and one-half on the second floor of 581 Fifth Avenue near 48th Street.

In contrast to a conventional retail establishment, Urban arranged items within sumptuous, contextual vignettes in spaces devoted to silver, gold, Gustav Klimt and “general exhibition.” The shop featured Austrian imports “representing 22 lines of artistic endeavor” as well as furniture of Urban’s own design, according to a 1922 New York Times article. While items reflected a variety of price points, lacework, leather accessories and other less expensive goods proved the most popular.

Table designed by Josef Hoffmann (1870–1956) and executed by Wiener Werkstätte, 1904. Ebonized oak with pores chalked white, boxwood inlay and silver-plated mounts. Minneapolis Institute of Art.

The short-lived New York experiment was not financially successful. By way of explanation, Staggs highlighted ongoing squabbles with the home office in Vienna as well as Americans’ preference for a mixed approach to interior decoration over the unified look championed by the Wiener Werkstätte. In her essay, Staggs also revealed that Urban sometimes became disturbed when customers showed too much interest in his favorite objects. The professional hazard of coveting one’s own merchandise may strike a sympathetic pang in some readers.

All in all, Americans were not ready for the advanced designs of the Wiener Werkstätte in 1922 and 1923. Staggs summarized, “Urban was ahead of his time. He offered a preview of the high-end luxury goods that would become popular during the late 1920s. If only he could have held out until after the 1925 Exposition internationale des arts décoratifs et industriels modernes in Paris, he would have found a more receptive audience and could have done better.”

During the era when Urban was absorbed with the idea of bringing the Wiener Werkstätte to America, he also served as the art director for Cosmopolitan Productions. Urban imbued some of the films he collaborated on with a Secessionist flavor. Urban is recognized for the contemporary look he gave Enchantment, 1921, considered the first American movie to show avant-garde décor. He even used some of the objects available for purchase in his New York showrooms as props in later films. Regarding his desire to disseminate the design ideals of Wiener Werkstätte, Joseph Urban may have wielded the greatest influence as a tastemaker through set design.

The almost 600-page exhibition catalog is a work of art in itself. It contains high-quality images of objects in the exhibition as well as period photographs of interiors and exteriors. Nearly a dozen leading scholars have contributed their latest research. Some of their essays are devoted to specific media (for example, metals, furniture, bookbinding and leather) while others address subjects including “Klimt and the Wiener Werkstätte,” “Garden Architecture” and “Palais Stoclet,” the last the penultimate project Josef Hoffmann and the Wiener Werkstätte realized in Brussels. Also noteworthy is the considerable attention paid to the business side of the Wiener Werkstätte, in other words, the financial and retailing elements. The catalog also contains a corporate timeline as well as an illustrated list of makers’ and designers’ marks. The handsome and comprehensive volume is an essential acquisition for those interested in Twentieth Century decorative arts.

Art and design aficionados should not miss this extraordinary exhibition. It will astound serious students of the Wiener Werkstätte as well as those less familiar with the firm’s oeuvre. Such a rich display of Wiener Werkstätte and Viennese Secessionist decorative arts is exceedingly rare, and likely will not occur in the United States again soon. Get to the Neue Galerie New York any way you can.

“Wiener Werkstätte 1903-1932: The Luxury of Beauty” closes on January 29. The Neue Galerie New York is at 1048 Fifth Avenue. For more information 212-628-6200 or www.neuegalerie.org.

Kate Eagen Johnson is an expert in American decorative arts and an independent museum consultant, historian, lecturer and author.