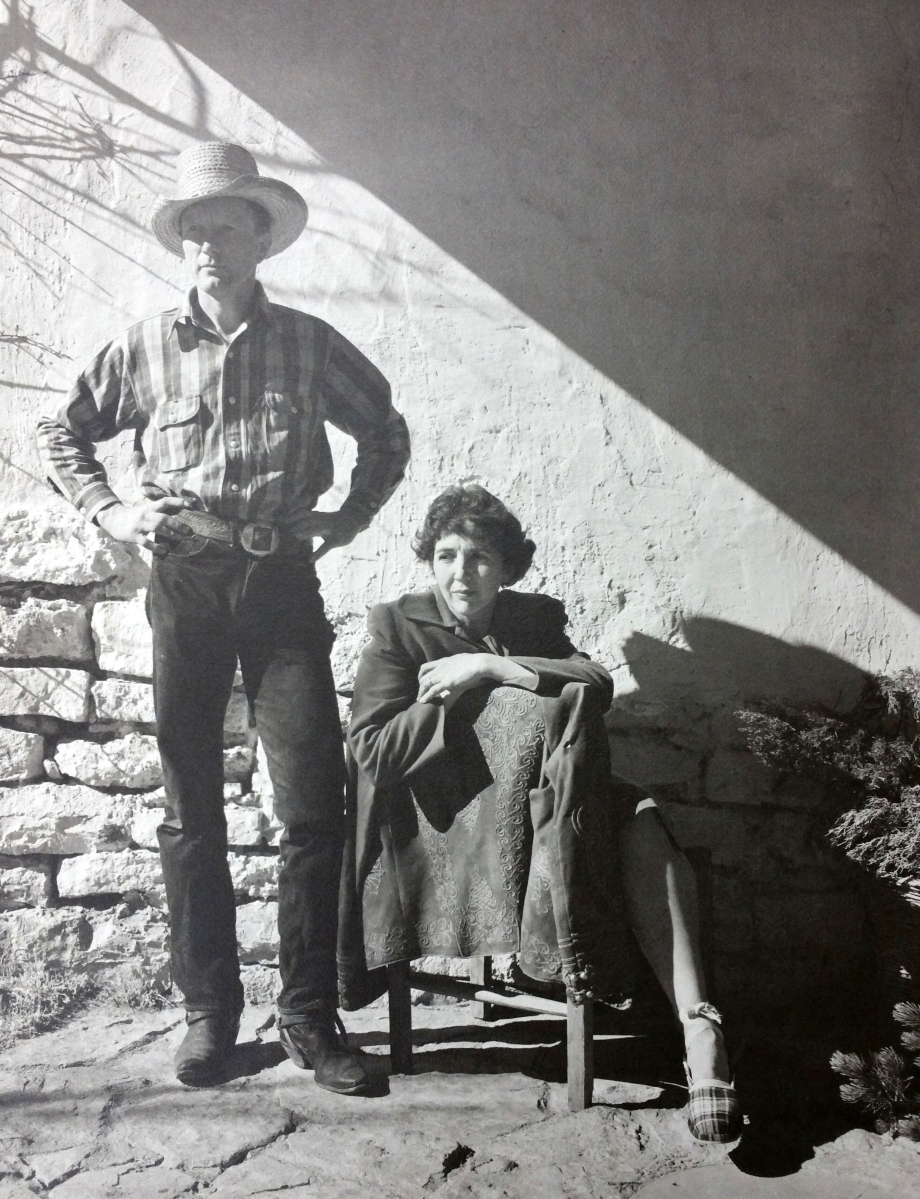

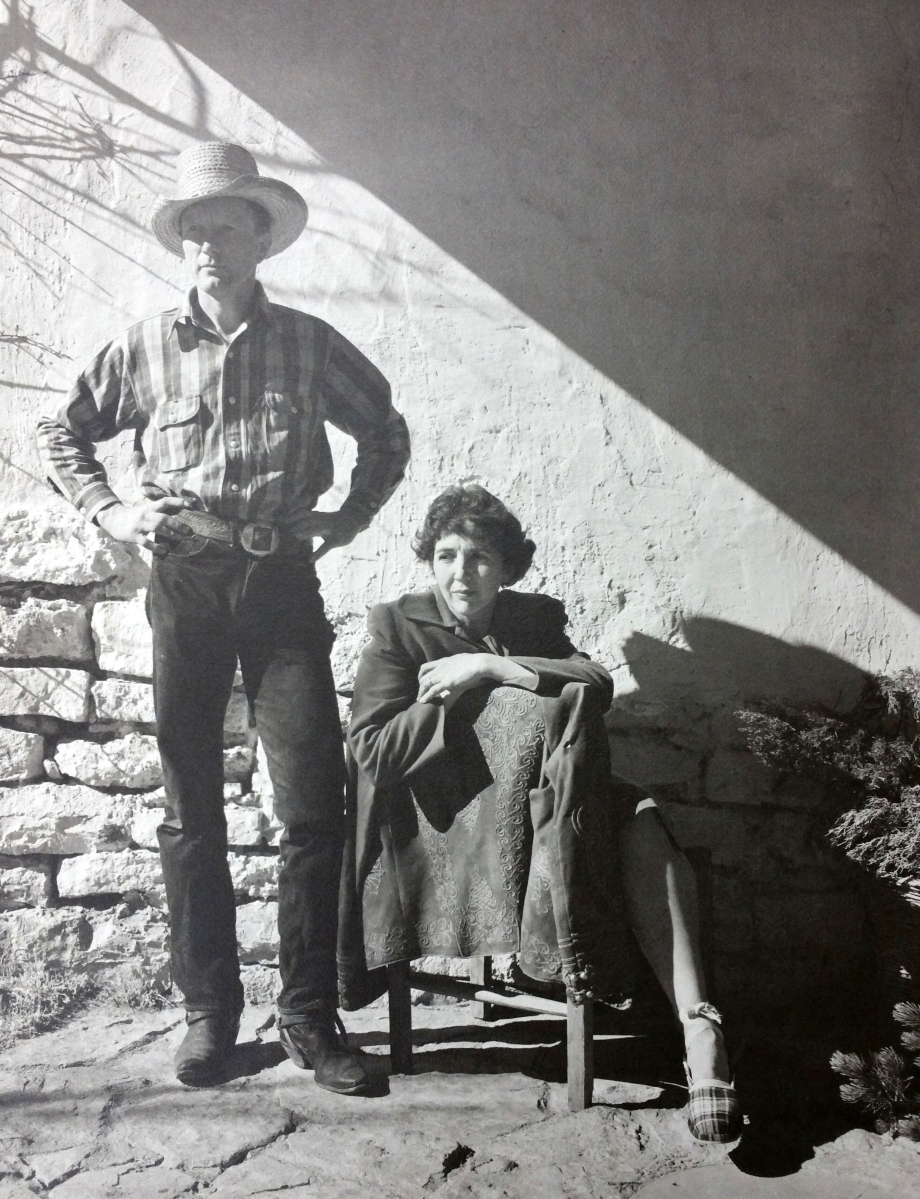

“Peter Hurd and Henriette Wyeth” by Walton Wray Wiggins, 1944. Silver print on paper. Roswell Museum and Art Center.

By Jessica Skwire Routhier

DOYLESTOWN, PENN. – The title of the exhibition “Magical & Real: Henriette Wyeth and Peter Hurd, A Retrospective” at the James A. Michener Museum through May 6, reflects a complex, dual subject. This is a show with two different, seemingly contradictory themes and two different artists whose stories similarly intertwined, competed and coalesced. Peter Hurd, the young military cadet from Roswell, N.M., was almost completely self-taught as an artist. He first encountered Henriette Wyeth, the 16-year-old girl from rural Pennsylvania, a scion of one of America’s leading artistic families, through her father, N.C. Wyeth. The bond between Peter and Henriette became a permanent one when they married, creating a complex network of relationships and influences that spanned generations and many miles.

These artistic and familial links were crucially important – even defining – for both artists, and yet their work, for all that it intersected, remained distinct. How, then, can one exhibition give each artist his or her due? This is the challenge posed by the Michener Museum and the co-organizing Roswell Museum and Art Center, which will present “Magical & Real” June 15-September 16.

One solution, according to exhibition curator Kirsten Jensen, has been to create a two-volume catalog, effectively giving both artists their own monograph. Volume I includes three chapters dedicated to Henriette Wyeth, all by Jensen. Volume II has three essays about Peter Hurd by three different authors, including the Roswell Museum’s Sara Woodbury, the exhibition’s co-curator.

“Henriette is always being described in relation to somebody else; I thought that she needs to stand on her own,” Jensen said in a recent conversation. Woodbury concurred, adding that the layout of the exhibition in each venue has been designed to give “each artist his own section, his own voice … Especially with Henriette Wyeth. She tends to be lumped together with the Wyeth men in her life.”

The introductory section of the show both confirms the truth of that statement and teases it apart. Three late 1930s portraits by Henriette include one of N.C. Wyeth, seated in front of his Maine canvas “Island Funeral” and staring penetratingly at the viewer; one of Peter, similarly seated in front of one of his own New Mexico landscapes, his gaze veering off to the left; and, in the center, a self-portrait of Henriette, holding a bundle of wildflowers aloft in a seemingly disarming gesture belied by her direct and level eye contact with the viewer. “It really is this bravura display of her talent. If you see nothing else in the show except those three portraits, you get it,” says Jensen.

The introductory section of the show both confirms the truth of that statement and teases it apart. Three late 1930s portraits by Henriette include one of N.C. Wyeth, seated in front of his Maine canvas “Island Funeral” and staring penetratingly at the viewer; one of Peter, similarly seated in front of one of his own New Mexico landscapes, his gaze veering off to the left; and, in the center, a self-portrait of Henriette, holding a bundle of wildflowers aloft in a seemingly disarming gesture belied by her direct and level eye contact with the viewer. “It really is this bravura display of her talent. If you see nothing else in the show except those three portraits, you get it,” says Jensen.

To be sure, one of the surprises of the show, even for those familiar with hypertalented extended Wyeth family, is that Henriette was no hobbyist, but in fact a serious, academically trained, career artist with a rigorous practice. She was the eldest of N.C.’s five children, the one he first took under his wing to carry on his artistic legacy, and arguably the most naturally talented. N.C. was fully cognizant of Henriette’s nascent abilities, Jensen points out. N.C. frequently wrote to friends about how in awe of Henriette he was, but he never told her so in so many words. Fearful of spoiling her, or letting knowledge of her natural skill go to her head, he instead offered unfiltered criticism as part of her rigorous training.

Even while Henriette took classes at the Boston Normal School (the Wyeth family was briefly based in Massachusetts) and the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA), her father remained her primary teacher. She continued to live at home, and because she was discussing her classes in person with N.C. every evening, there is little written record of her training. Some of the choices she made early in her career remain inscrutable for that reason. We do not know why, for instance, despite winning early awards at PAFA, she failed to submit a portfolio for a prestigious award that would have enabled her to study abroad.

We might reasonably suspect that it has something to do with the young man who showed up on the Wyeth doorstep in Chadds Ford, Penn., in 1923 seeking lessons with N.C. Henriette was only 16. “Hurd moved into a farmhouse less than a mile from Wyeth’s studio,” writes Woodbury in the catalog, “and was accepted as a member of the family, joining them in social gatherings and vacationing at their Port Clyde home in Maine.” Perhaps inevitably, N.C.’s two protégés fell in love. Their courtship was extended and marked by frequent separations – emotional and geographical – but both were still so young when they married in 1929 that they were only just beginning to find their mature artistic voices.

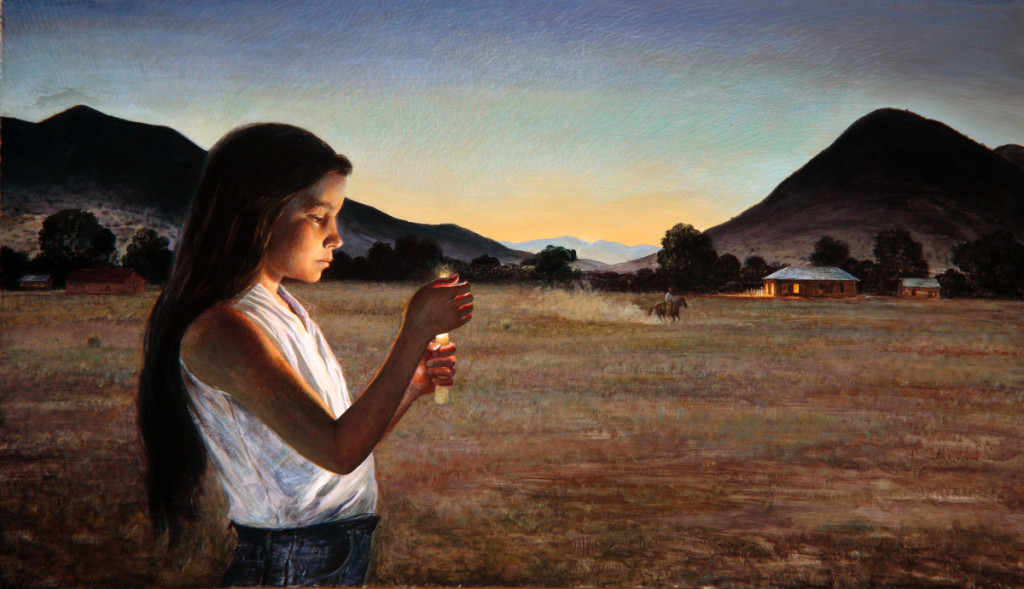

“Eve of Saint John” by Peter Hurd, 1960. Egg tempera on board, 28 by 48 inches. San Diego Museum of Art.

Henriette’s works from the years immediately preceding her marriage show the promising start of an aesthetic that was entirely her own. Her “Fantasies” – complex, Symbolist-inspired paintings that make use of the female figure and a vivid palette – show the influence of Marie Laurencin and others. In the end, they were Henriette’s own invention. One work, a mural-size painting now known as “The Picnic” that was rediscovered and conserved during the preparation of this exhibition, caught the attention of N.C., who framed and hung it over the grand piano in the Wyeth home. “He recognized that it was an important painting and a pure expression of Henriette’s artistic vision that was completely outside of him,” says Jensen.

For Hurd’s part, the late 1920s were a time of distinguishing himself as an artist from his teacher. Over more than five years, he had internalized N.C.’s distinctive, illustrative style, capably taking on his overflow commissions and creating alluring narrative works like “Legend of Ingham Spring.” But he had grown tired of this “Wyethian” approach, as he put it to a friend, fretting that his paintings were “right in every detail but the signatures.” He found respite, paradoxically, by returning to the place he had lived before he began to pursue art in earnest: New Mexico. During extended stays at his family home in Roswell, he produced vigorous and finely wrought portraits. The canvas titled “Don Rosario Ortega” is a standout example.

As time went on, he steadily incorporated the Southwestern landscape into his portraits, a successful gambit that helped him win an important purchase prize at the Art Institute of Chicago, for his “El Mocho” of 1936. This was one of the first paintings he did in egg tempera, a medium that he then introduced to his Wyeth relatives. The formula of a bust-length portrait in front of a rural landscape became a signature for him much as it did for his near-contemporary Grant Wood, with whom he also shared a fascination with windmills – a conceit explored by scholar Leo G. Mazow in his catalog essay. Works like “Oasis” and his textured, undulating “The Dry River” are key examples of the centrality of the Southwest landscape to his work.

The funds from the purchase prize for “El Mocho” allowed Peter and Henriette to acquire the land – in San Patricio, N.M., about 50 miles outside of Roswell – that would eventually become their own Sentinel Ranch. It was only at this point, says Jensen, that Henriette began to envision a home for herself in the Southwest. For years, she had traveled back and forth between New Mexico and Pennsylvania but retained a permanent studio only in Chadds Ford. Sentinel Ranch suddenly gave her her own space to paint in the Southwest.

Influenced no doubt by Peter’s work, Henriette made a sharp turn toward the “real” in her own artistic output at this time. The “Fantasy” paintings were by now a closed chapter, as she focused on portraiture and still life in the late 1930s and 1940s. This is when she painted the portraits of her father and her husband that open the exhibition, remarkable works that grapple with place, art and legacy. In the Michener display, the portraits are shown alongside her own self-portrait, but in the mind’s eye it is difficult not to also link them to Henriette’s portraits of her son, Peter, and of the teenaged Andrew Wyeth, posed in a Civil War uniform.

“Beulah Emmet” by Henriette Wyeth, 1933. Oil on canvas, 46 by 40 inches. Courtesy Gerald Peters Gallery, Santa Fe, N.M.

There are so many reference points here that span the generations – from the family fondness for playing dress-up, to N.C.’s body of work related to the Civil War, to Peter’s military career, to a kind of foreshadowing of the work of Andrew’s son Jamie. There are inklings here of that shared Wyeth aesthetic in which realism becomes “magical” realism. “There’s something behind that,” says Jensen. “There’s something deeper, there’s this psychological and emotional tension, and Henriette really captures that.”

Jensen sees something similar in Henriette’s flower paintings, among which one might include her previously mentioned self-portrait. “What fascinates her about flowers [is that] at the end of the season they will fade and crumble. You cut them and put them in a vase, [but] they’re dead.” That sense of memento mori is evident not only in her self-portrait but also in works like “Beulah Emmet” and in 1945’s “Iris,” conceived as a memorial to N.C., who died tragically that year. The painting has “this really black, flat background,” says Jensen, “and these flowers that seem untethered to anything – as if she’s really exploring … that veil between mortality and death that always fascinated her about flowers to begin with.”

Jensen says that the years after 1945 were a period of artistic decline, or at least diminished activity, for Henriette, but notes that there are still high points: “When she’s ‘on,’ it’s incredible.” She adds, “she has this way of creating dramas between objects,” with works like “Music Box” and “Jamie’s Pumpkins” – another prophetic painting – showing her continued strengths in still life.

Peter Hurd’s similar ability to wed observed reality to a sense of mythic human drama led to important commissions, some commercial – as in “Grading Tobacco,” made for a Lucky Strike advertising campaign – and some with loftier purposes. During World War II, Peter had the opportunity to revisit his earlier aspirations to a military career when Life magazine hired him to be a war correspondent, embedded with the US Air Force over Europe. Melissa Renn’s catalog essay discusses these wartime works and notes their profound influence on his brother-in-law Andrew Wyeth, whose 1940s paintings of, for example, soaring birds have been connected to a fascination and horror with the destructive power of flight.

That link between Peter’s topical, of-the-moment work and Andrew’s seemingly more detached and eternal themes underscores the fact that, for the extended Wyeth family, there was no bright line between the magical and real. For all of Hurd’s resolute realism, the “Wyethian” magic is a notable presence in his later work, just as it is for Henriette’s. Works like “Gate and Beyond” and “Eve of Saint John” – so evocative of Henriette’s portraits of young people, from “Beulah Emmet” to “The Music Box” – similarly convey the shadow side of nature, youth and potential that has long been, and continues to be, a distinguishing characteristic of the Wyeth painting tradition.

Visitors to the Michener venue may also be interested in “Southwestern Son: The Lithographs of Peter Hurd,” on view through July 8 at the Brandywine River Museum, a Chadds Ford institution known for its holdings of Wyeth family art.

The James A. Michener Museum is at 138 South Pine Street. For information, www.michenerartmuseum.org or 215-340-9800.

Jessica Skwire Routhier is managing editor of Panorama, the journal of the Association of Historians of American Art. She lives in South Portland, Maine.

_preview.jpg)