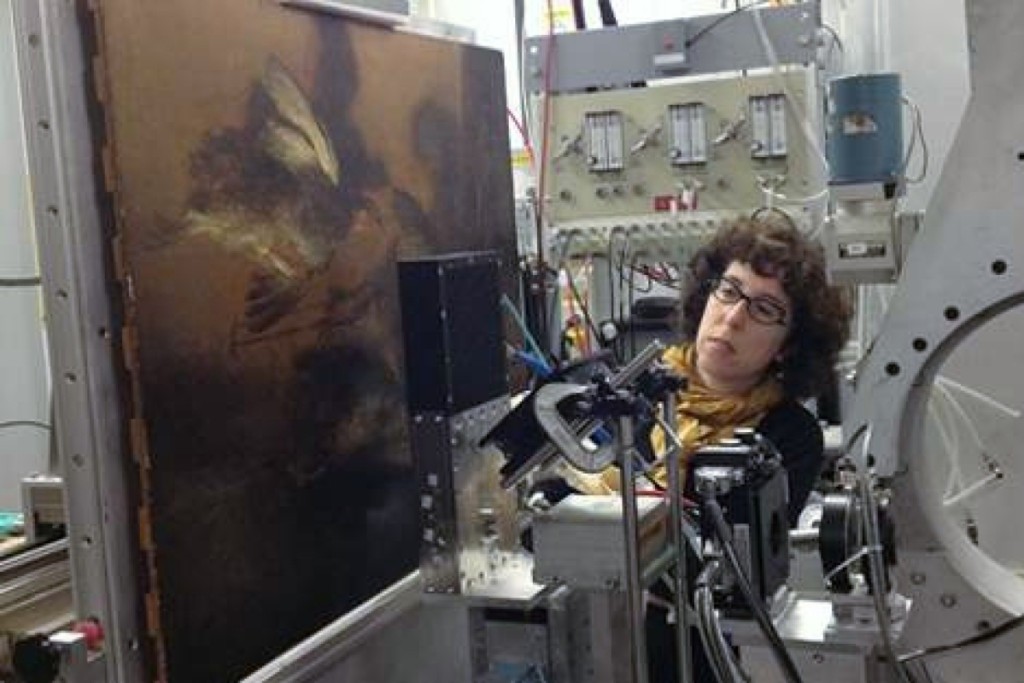

Jennifer L. Mass is the Andrew W. Mellon professor of cultural heritage science at Bard Graduate Center for Decorative Arts, Design History and Material Culture. She is also president of Scientific Analysis of Fine Art, a go-to firm for analyzing and authenticating fine and decorative art. It’s a busy profession these days, judging by the fact that, according to Switzerland’s Fine Art Expert Institute, 50 percent of art circulating on the market is being forged or misattributed.

Half of the art on the market at auction and at shows is fake? Does that sound right to you?

I hear this question a lot, and it is a challenging one. Authenticity issues are highly dependent on the segment of the art market one works in. I have encountered significant problems with antiquities, folk art of all forms, American furniture – mostly issues with pastiches – trade silver, European porcelain and Chinese porcelain, both imperial and export. The early Modernists, such as Amedeo Modigliani, comprise another area of difficulty, as do Old Masters and the Abstract Expressionists. Because people come to me when they have a suspected problem with attribution or authenticity, my view of the market is quite slanted. I can see single-dealer collections with 70-90 percent of the pieces being wrong. However, a number between 40 and 50 percent for the art market overall is more realistic.

So many techniques now to verify paintings – X-rays, infrared scans and radiocarbon dating, among others. Is technology supplanting connoisseurship or the trained eye? Is there a danger in letting the machines take over?

Technology will never supplant connoisseurship; it is an orthogonal approach to be used in conjunction with a stylistic analysis. Cultural heritage scientists, in the best-case scenario, always work together with art conservators and art historians to obtain the best possible assessment of a work. Also, we call them scientific instruments and not machines, the term “machines” hurts their feelings!

Rational humans almost always get an appraisal before buying a home. Why are some collectors so prone to buying high-value art that lacks documentation?

There is competition among collectors to buy from the big-name dealers and to be called first when an exciting find comes to light. If a collector makes the purchasing process difficult for the dealer by having conservators, scientists and lawyers get involved prior to the transaction, they may not receive the first phone call about the next exciting find. As a result, many times we see people doing their due diligence after the sale. Dealers are getting more used to having conservators inspect works before purchase, and my hope is that in time scientific study will become a natural part of the process too. If that does not occur, sales can always be written so that if any problems turn up later through scientific analysis, the buyer has appropriate recourse. Art fairs like TEFAF use scientific analysis to vet many works prior to the fair, and this is helping introduce science into the prepurchase process.

For paintings, fakes can be spotted through catching overpainting, inappropriately aged canvas or pigments that didn’t exist at the time they were purportedly painted. What’s the process for decorative arts pieces, such as an antique weathervane or a Staffordshire figurine?

With weathervanes, we have found a number of issues with the finishes, and often these pieces are desirable for their beautiful finishes, whether gilded, polychromed or patinated. The beauty of a natural patina cannot be replicated with an artificial brushed-on copper nitrate patina, which looks flat and shiny by comparison. A natural patina has a rich velvety appearance of copper minerals growing directly out of the surface of the vane. Naturally, aged gilding is imitated using gold flake painted on with anything from Elmer’s Glue to polyurethane floor finish. These modifications are not detectable to the naked eye, but they are detectable using molecular analysis techniques, such as infrared spectroscopy. X-ray fluorescence of the Staffordshire figures can determine whether their overglaze enamels are consistent with the specific technologies used at Staffordshire and the date of manufacture.

So after one has learned how to distinguish Chippendale from Hepplewhite, how does one become a furniture finish detective?

The furniture finish projects are some of my favorites. By removing microscopic samples of the finish – smaller than the period at the end of this sentence – and mounting and polishing them to reveal their layer structures in cross-section, we are then able to view them under the microscope in ultraviolet light. This allows us to view the layer structures of the finishes on different parts of the piece, and to study the compositions of the finish layers. If the early layer structures don’t match, then the different components of the piece likely did not start out their lives together, and the work is a pastiche.

Seeing the forest for the trees, has your forensic work in fine art over the past 20 years given you an appreciation for any particular genre?

Essentially, I love working on all types of art, because they are beautiful on both the macroscopic and microscopic scale. Art Nouveau and the Jugenstil movement are tremendously appealing to me, as is the Russian Avant-Garde, but we see a number of authenticity concerns for the latter.

Best memory (not related to work) from your travels to Oslo to study Munch’s “The Scream” for a pigment degradation study?

Riding the escalator in the airport and seeing tremendous banners reading “Welcome to Oslo, ‘The Scream’s’ Hometown.” This brought home what an icon this work is for the city, the nation and for the Western art canon.

-W.A. Demers