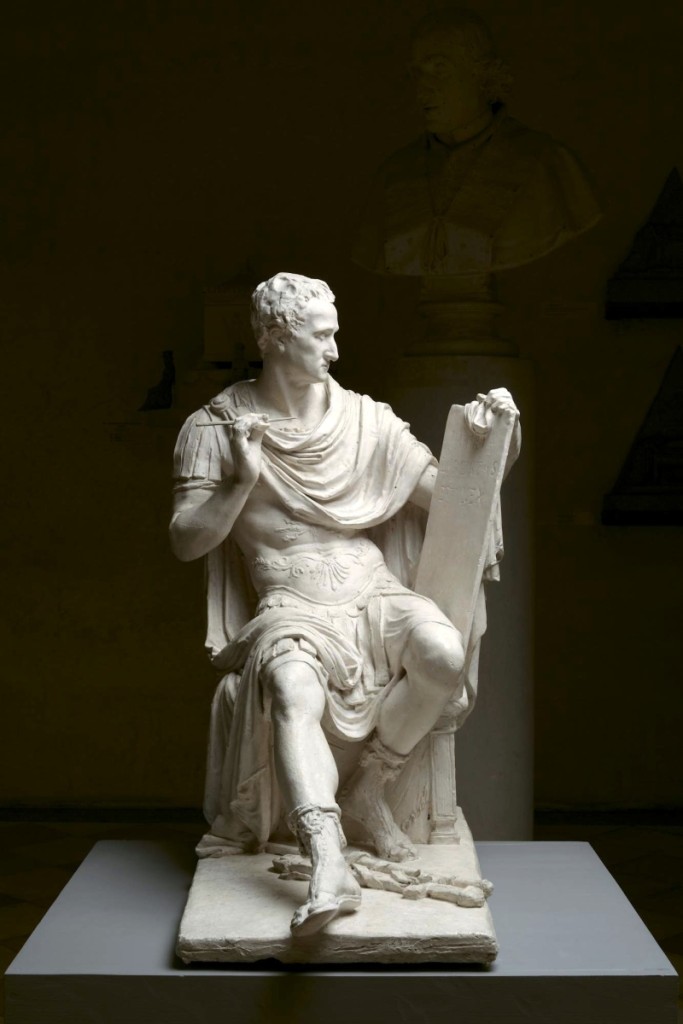

Bozzetto for “George Washington” by Antonio Canova, 1817, plaster, 31½ by 18-1/8 by 25-9/16 inches. Gypsotheca e Museo Antonio Canova, Possagno Fondazione Canova onlus, Possagno. —Fabio Zonta photo

By James D. Balestrieri

NEW YORK CITY – The story tells itself. In 1816, the legislature of the state of North Carolina authorized the commission of a monumental statue of George Washington – founding father, hero of the American Revolution, first president of the United States. From his retirement in Monticello, Thomas Jefferson – founding father, diplomat, third president of the United States – weighed in, insisting that the only sculptor for the job was the Italian master Antonio Canova (1757-1822), whose studio was in Rome. By 1821, Canova’s monumental marble was installed in the State House in Raleigh. But a scant decade later, fire swept through the Capitol. The roof caved in and crushed Canova’s masterpiece. Now, Canova’s life-sized plaster modello for the work, on loan from the Gypsotheca e Museo Antonio Canova, in Possagno, Italy, is on view at the Frick Collection through September 23. But behind the story – beautifully told in the accompanying catalog Canova’s George Washington by Xavier F. Salomon with contributions by Guido Beltramini and Mario Guderzo – lies a host of questions: about civic art and its uses; about the design of Canova’s “Washington,” its intentions, lingering meanings and nagging questions; about history and the place of art in the collective memory. The story of Canova’s “Washington,” the one that seems to tell itself, has prequels and sequels and leads, sometimes metastatically, down darker paths.

To begin, go back. During discussions that began in 1786 surrounding a commission in which the French sculptor Jean-Antoine Houdon (1741-1828) was to be engaged to carve Washington in marble for the Capitol in Richmond, Va., Washington, famed for his modesty and committed to the supremacy of the citizen over the soldier, vetoed the idea of being immortalized in Classical dress – that is, Roman armor and robes. Washington stated, “a servile adherence to the garb of antiquity might not altogether be so expedient as some little deviation in favor of the modern costum… [sic]” Jefferson wholeheartedly agreed and Washington, as he stands in Richmond to this day, is in a uniform not so very different from the clothes of a gentleman. A sword dangles from the 13 fasces while a walking stick speaks to the general as gentleman. The plow Washington rests on speaks to the gentleman as gentleman farmer. It is also worth keeping in mind that Houdon sailed to America and stayed with Washington at Mount Vernon. Houdon sculpted a magnificent terracotta bust from life and took that, as well as a life mask of Washington, back to Paris with him.

Thirty years later, Jefferson, in a letter reproduced in the catalog about Canova’s commission, wrote persuasively, “I am sure the artist and every person of taste in Europe would be for the Roman, the effect of which is undoubtedly of a different order, our boots & regimentals have a very puny effect…”

What had changed? The United States? Jefferson? What might this change have meant? Guderzo and Beltramini articulate the parameters of these questions. According to Guderzo, Canova’s representation of George Washington, in line with Classical interpretations of Zeus seated, transforms our first president into “a Roman general, or, more accurately, as an emperor.” Conversely, Beltramini’s essay states, categorically, that Canova “effectively made Washington a hero of ancient Republican Rome.”

The gulf between a hero of the Roman Republic and a Roman Emperor yawns; in Washington’s mind, it was the difference between Julius Caesar, making his play for all of Rome, and Cato, dying in the field in a tragic, valiant, but hopeless cause against Caesar’s armies. Cato was Washington’s personal hero. His favorite play was Joseph Addison’s Cato, and even against the censure of Congress, Washington organized a staging of the play at Valley Forge, though its theme made it, perhaps, a less than ideal morale booster.

By 1816, the United States had fought off another invasion by Great Britain.America was rapidly becoming a key player. After winning the Battle of New Orleans, the shadow of Jacksonian populism was beginning to loom. Jefferson’s sitting vice president, Aaron Burr, had killed an American icon, Alexander Hamilton, in a duel. In the United States, things were already decidedly imperial. Even more darkly, Jefferson and others, who had not fought in the Revolution, had long come to political blows – Republican against Federalist – with those, like Washington and Hamilton, who had. The young nation was rife with parties, factions and gossipy, mouthpiece newspapers, some of the very things the founders had warned against.

By 1816, the United States had fought off another invasion by Great Britain.America was rapidly becoming a key player. After winning the Battle of New Orleans, the shadow of Jacksonian populism was beginning to loom. Jefferson’s sitting vice president, Aaron Burr, had killed an American icon, Alexander Hamilton, in a duel. In the United States, things were already decidedly imperial. Even more darkly, Jefferson and others, who had not fought in the Revolution, had long come to political blows – Republican against Federalist – with those, like Washington and Hamilton, who had. The young nation was rife with parties, factions and gossipy, mouthpiece newspapers, some of the very things the founders had warned against.

So if the function of civic art is to commemorate events, validate a civic notion of progress and endorse the values of the community, was Jefferson, through Canova, asserting that the United States of 1820 was already a different place from the United States in 1786, a place in need of a superhero protector, martial symbolism and a national myth? Does Washington’s antique Roman armor represent a republic under siege, an empire protecting its interests, or both? Or were Jefferson’s motives for wanting Washington depicted in armor more personal, a way to distinguish his legacy as a man of peace and law, as opposed to Washington, the man of arms? Washington did, indeed, lay down his arms, like the Roman Cinncinatus – to whom Washington was, and still is, often compared – and return to his farm, but Canova’s sculpture does not convey this directly.

Compare the head of Washington as Canova conceived it with Houdon’s head and another in the exhibition by Italian sculptor Giuseppe Ceracchi (1751-1802), who did his version of Washington from life in the 1790s. The jawline in Houdon’s head is softer and jowly and the nose has only a small bump. Washington’s eyes are both careful and careworn but the mouth is set and firm, as if the old campaigner is contemplating his next move. Ceracchi’s “Washington,” by contrast, has the square jaw of the emperor general, a sacker and builder of cities, Caesar Augustus or Constantine. Canova sculpts Washington with a high, Ciceronian bulge in his forehead, the receding hairline of the philosopher and legal scholar, and an aquiline nose and long face not unlike that of Basil Rathbone.

Washington’s hair, in all of Canova’s bozzetti tabletop plaster models, and in the life-size modello, displays an unruly romanticism, as in Sir Thomas Lawrence’s portrait of Canova, painted even as the sculptor was working on the Washington commission.

Canova knew little of Washington or the American Revolution, but he had an assistant read him a book on the subject in Italian as he worked. Perhaps because of this, there is an evolution in symbolism in the various bozzetti. The texts on the tablets Washington holds move from proclaiming laws to the opening words of his Farewell Address, in which, famously, he cautioned against party and factionalism and championed love of country over allegiance to state. Even as the tablet text changed, so did elements in Canova’s composition beneath Washington’s seat; they morph from crown and scepter to sheathed sword and baton.

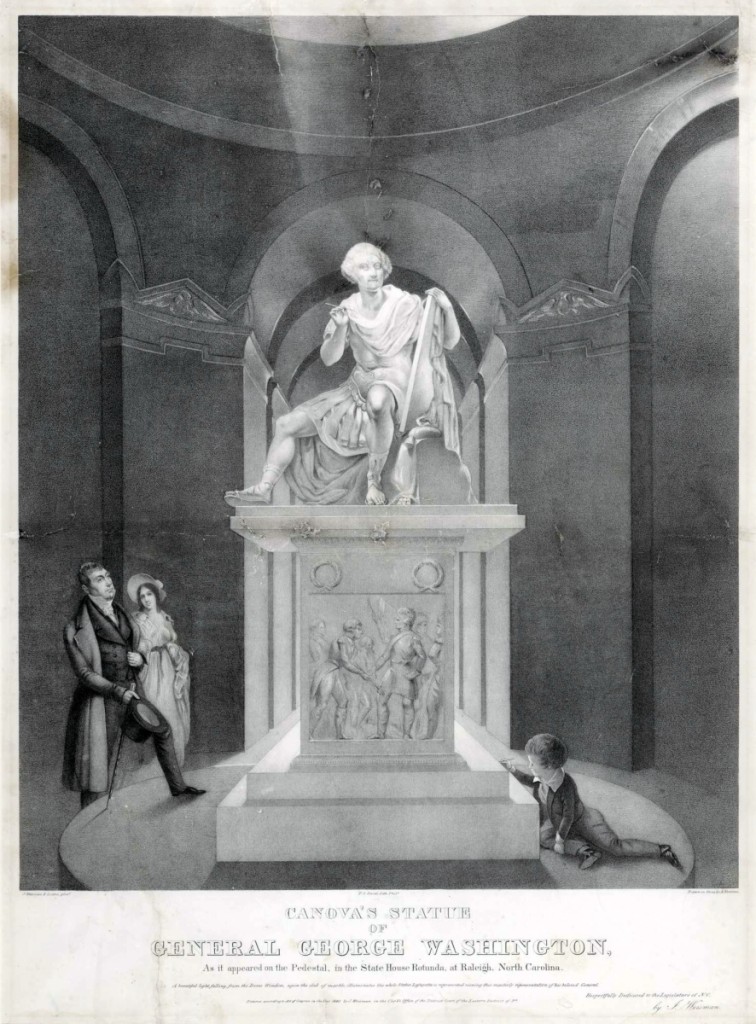

My favorite image in the exhibition is Albert Newsam’s lithograph “The Marquis de Lafayette Visiting the State Capitol in Raleigh in 1825,” done 15 years later after imagery by Emanuel Leutze, of “Washington Crossing the Delaware” fame, and Joseph Weisman. The sculpture in the print bears little resemblance to Canova’s destroyed marble; it looks more like Stuart’s George Washington, and Houdon’s. What intrigues me is the kid at lower right drawing or scratching – his name, initials or maybe a rude adolescent drawing – on the pedestal. I want to believe that he is Leutze’s creation, Leutze the perpetual revolutionary and committed egalitarian, but I cannot be certain. America, this young graffiti artist suggests, is not set in stone. It invites and expects us to add to it, to want to make our mark.

“The Marquis de Lafayette Visiting the State Capitol in Raleigh in March 1825” by Albert Newsam, after Joseph Weisman and Emanuel Leutze, 1840s, lithograph, framed 34½ by 28½ by 1 inches. North Carolina Museum of History, Raleigh, N.C.

Marks become signifiers as you walk around the modello, pins in the plaster, for example – used to mark measurements when the work was ready to be transferred from plaster to marble – protrude in a work-in-progress way, here and there. You cannot see the pins in the images, but when you look at the modello in situ at the Frick, they summon thoughts of slings and arrows suffered, of saints pierced, of heroes and how the selfsame world that loves them loves to take its shots at them, too.

Little remains of so many past civilizations. So little, it is as if we are trying to know an elephant only by its tail. Fragments of marble and stone, a few bronzes, weapons, broken walls, footnotes in contemporary writings. Fragments. Like the Egyptian god Osiris, Canova’s “Washington” was rent into fragments and scattered. Unlike Osiris, “Washington”‘s pieces have never been brought together and restored. In fact, it seems that some of the fragments of the marble have been broken into smaller parts, while others, including the head, are, for the moment anyway, lost.

The creation and fate of Canova’s “Washington” reminds us of the fragility of art. This, in turn, reminds us of the fragility of all human endeavor and institutions. Democracy, freedom, equality and the rule of law seem enshrined, carved in stone, but they are far more susceptible than marble. They can be twisted, compelled to fit ignoble ends and even scorched and shattered. George Washington knew firsthand that the Revolution was a near thing, that victory was not at all inevitable and that we need not look to the ancient world to find the fragility in our better natures and best laid plans.

Canova’s George Washington is published by D. Giles Ltd., in association with the Frick Collection.

The Frick Collection is at 1 East 70th Street. For more information, 212-288-0700 or www.frick.org.

Playwright, author and critic James D. Balestrieri is director of J.N. Bartfield Galleries in New York City.