“Two Cowboys in the Saddle” by Carl Rungius, 1895–1950, oil on canvas, 24 by 31-15/16 inches. Bequest of William N. Beach. Photography by Andy Duback.

By Jessica Skwire Routhier

SHELBURNE, VT. – There was some anxiety in Vermont when Shelburne Museum curator Kory Rogers announced his intent to organize an exhibition on cowboy culture. Would the show rely upon exhausted, prejudicial stereotypes of “cowboys and Indians?” Or would it veer in the opposite direction and take an overtly political, strident tone? In the end, Rogers found the middle ground between celebration and condemnation by yoking these present-day anxieties to those that characterize the time in which the works on view were produced. Challenging in every sense of the word, “Playing Cowboy” is on view at Shelburne Museum through October 21.

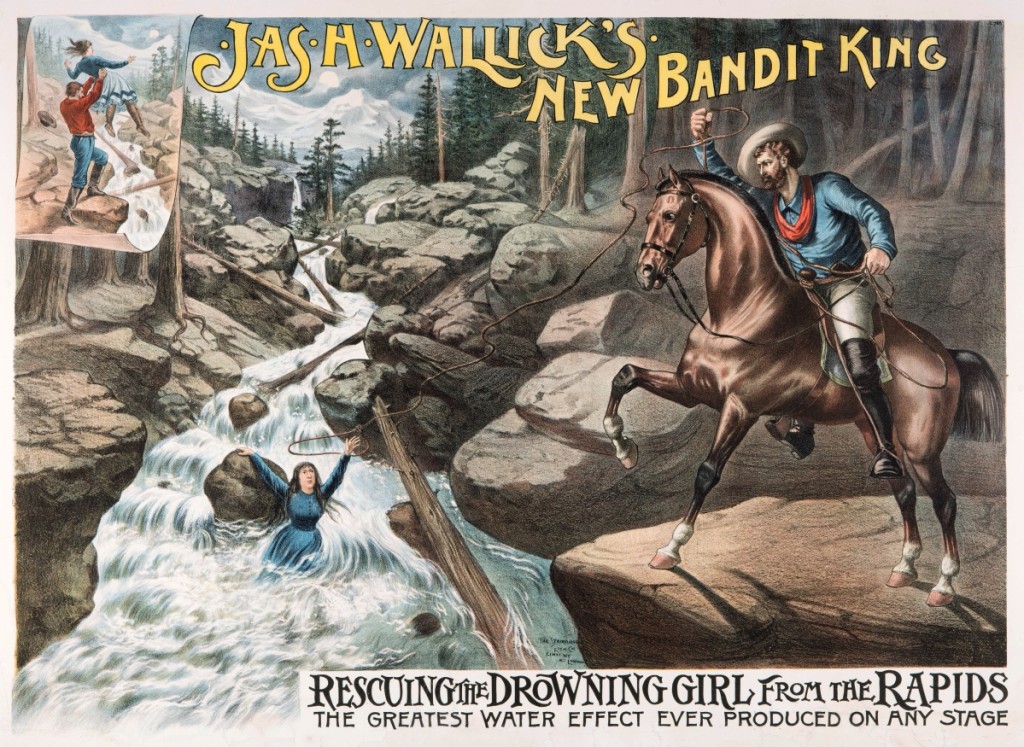

Another word for anxiety is “fear,” a pervasive theme throughout the Nineteenth and early Twentieth Century works on view in “Playing Cowboy.” The dashing buccaneers of the Wild West are almost invariably cast as heroes, bravely dispatching fearsome threats of various kinds – from hostile tribesmen to masked brigands to the harsh natural landscape. This is particularly evident in a series of posters advertising the Bandit King Wild West shows starring James H. Wallick – which Rogers has determined were loosely based on the life of Jesse James but turned the outlaw into a protagonist named Joe Howard. On one poster, Howard rescues a young girl from drowning in the foaming rapids; in another, he faces off against a knife-wielding opponent. An inset also shows him leaping across a rocky gorge over a burning bridge, with a blond child clasped in his arms.

The posters, which Rogers found interspersed among Shelburne’s famed collection of circus posters, were in fact the genesis of the present exhibition. Although Rogers is a native of Oklahoma, where Wild West culture is ubiquitous, he had never really engaged with the theme during his youth. Confronted with the imagery in the posters, and having recently curated an exhibition of Shelburne’s circus posters (“Papering the Town,” 2016), he found himself wanting to better understand what Wild West shows were, and what they shared – and did not share – with circuses.

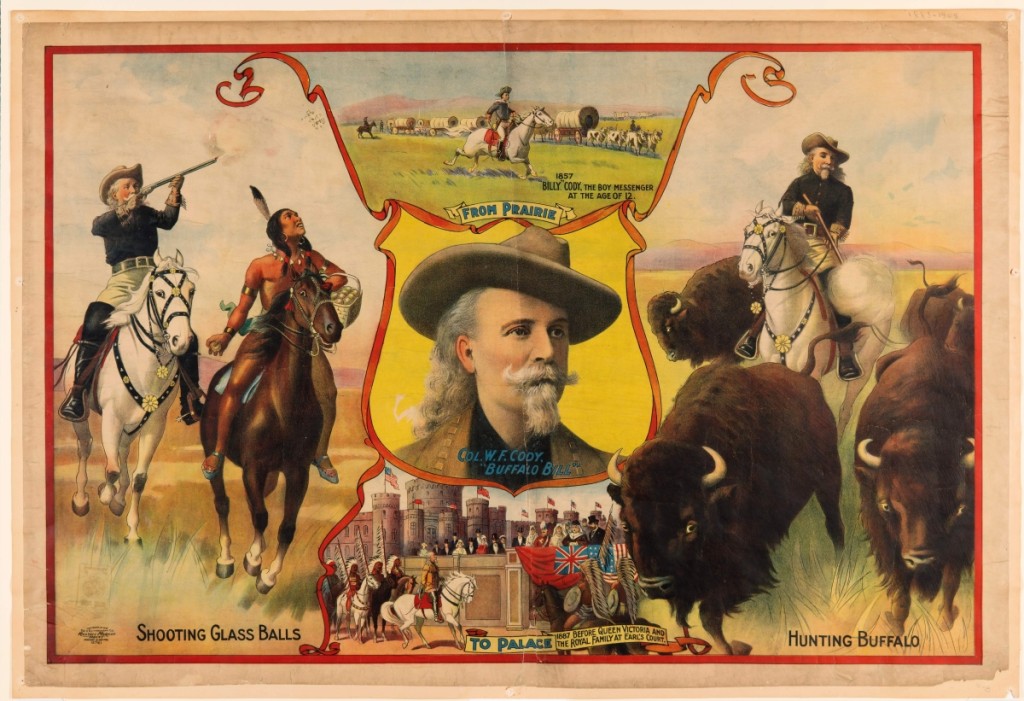

“[They were] organized in similar ways, they traveled in similar ways,” says Rogers, “but they focused on Wild West themes like cowboys and Native Americans.” As he discovered, some Wild West shows, like the Bandit King, began as stage shows. Even in this limited format, performances favored dramatic special effects over trained thespianism. In fact, some of the actors were not even human; one poster for Wallick’s show promotes the horses Bay Rider and Roan Charger as “the most wonderful animal actors on earth.” Probably because of these ambitious staging elements, Wild West shows eventually moved to outdoor arenas, the format preferred by the primary innovator of the genre, “Buffalo” Bill Cody. Featuring horses and buffalo, authentic cowboys and Native American actors, and dazzling displays of sharpshooting and trick riding, Wild West shows offered a safe way for audiences to experience the allure and the danger of the American West. The posters tantalizingly offered previews of these thrilling but managed experiences.

The fear manifested in these images is a safe, pleasurable one, felt on behalf of others and assuaged at the same moment that it is introduced. The posters and performances provided reassurance that fears about the West were fixable, at least in the hands of a valiant cowboy.

Fear, of course, is not unambiguously bad; it serves an important purpose as a protective response. Much like a bucking bronco, however, fear unharnessed can be difficult to control. It is this unbridled fear that is the subject of Charles Deas’s “The Death Struggle,” showing a white frontiersman and a Native American brave, eyes bulging, then plummeting to their deaths even as they maintain their mounts and brandish their knives. While it is unclear what has precipitated their dispute and their fall, there can be no doubt that the worst has happened, and there will be no happy ending: not even Joe Howard could save them now.

“The Death Struggle” demonstrates the ambiguity of the many fears that were layered over the Western frontier. Americans of varying stripes were both afraid of Native Americans and afraid for them, as we saw the ground increasingly fall from under their feet. We were afraid of hunger, thirst and exposure in a seemingly limitless, unpitying landscape, but we were also afraid that the wilderness would disappear as it became settled. And we were afraid of lawlessness and social and moral anarchy, while we also feared the long hand of the federal government. One way to quell such perceived threats was to identify them and attempt to describe and understand them, an approach that artists have long used to dissect racial and ethnic fears. This “pseudo-anthropological” approach – Rogers’s term – can be seen in Indian Tribes of North America, a lavishly produced book featuring portrait lithographs of indigenous Americans by Charles Bird King. Thus recorded and cataloged, Native American leaders were perceived (by the invariably white readers) as objects of curiosity, rather than agents of fear. In the book, of course, complex individuals are meant to stand as representatives for entire diverse populations; Rogers has mitigated this to some extent by including extended biographies of the people depicted.

Wild West shows capitalized on that vaguely ethnographic curiosity. Audience members were thrilled to be in the presence of “real Indians” and reveled in the details of their costume and speech, authentic or not. A poster from 101 Ranch, which hosted shows in Oklahoma and beyond in the first years of the Twentieth Century, used stereotypical Native American imagery to advertise the show’s main attraction. Even earlier than that, though, anthropology merged with entertainment, exploiting the seemingly innocent interest in Native American physiognomy and costume for commercial purposes. The Shelburne exhibition includes three rare, recently conserved portraits of Native American leaders that are painted on semitransparent cloth. “We think they were part of a traveling show that would have displayed them…backlit by candles,” Rogers notes. The illuminated display at Shelburne Museum – a feat of conservation work in and of itself – gives some sense of the original spectacle.

“Col. W.F. Cody ‘Buffalo Bill’” by US Lithograph Co. Russell-Morgan Print, 1883–1910, lithographic print on paper, 28-3/8 by 41 inches. Museum purchase, acquired from Roy Arnold. Photography by Andy Duback.

The subjects of such presentations were generally depicted in an idealized way, a trope that passed into literature and film and came to be known as the “noble savage.” Seen in the context of loss and forbearance, Native Americans lost their threatening veneer and instead became an object of paternalistic sympathy and respect – even a defining symbol of American-ness. Shelburne’s show includes a wall of five carved, life-size cigar store figures, who carried that American “brand” into taverns and general stores across the United States and beyond. The carvings convey “more than a tinge” of racism, Rogers acknowledges – several wield tomahawks and one a real rifle – but despite this, or perhaps partly because of it, they are well worth confronting as culturally rich artifacts and works of art.

The mirror image of the cigar store figure is the lone cowboy, also featured in many of the works on view. Where the “noble Indian” uneasily emblematized America’s past – things once feared and now consigned to nostalgia – the cowboy stood for the promise of the future. Carl Rungius’s oil painting of two stoic cowboys looking out over an empty plain (save for a tiny third cowboy in the distance) erases both the troubled and bloody history of the West and the complexity of its present moment of rapid industrialization: what is left is only raw, unfettered opportunity.

Even as cowboys themselves were becoming a relic of the past – and Rogers points out that even in their heyday there were not as many of them as we might believe, and they were by no means all universally white – the cowboy spirit of America as a whole continued in full force. With the West “won,” Americans soon sought to conquer new frontiers: industry, technology and ultimately space – part of the reason that the popularity of the cowboy entertainer endured through the postwar era. One can see predecessors of television’s Lone Ranger and The Rifleman in Wild West show posters that depicted the heroic cowboy, the star of the show, front and center, flanked by his loyal steeds (Bandit King), by the chaotic forces of a nonwhite world (101 Ranch Real Wild West), or by stories from his life and exploits (Col. W.F. Cody “Buffalo Bill).

“Buffalo” Bill Cody’s life and public persona characterizes America’s fascination with the cowboy era as well as any one individual can. In his youth, Cody had been a champion buffalo hunter in the service of the railroads. “It was their strategy to suppress Indian uprisings,” Rogers notes, “by killing off this herd that was so important to their culture.” Cody also served as a scout in the US cavalry during the Plains Wars, which killed and displaced many thousands of Native Americans. And yet, as a civilian and a showman, Cody professed sincere respect for Native American culture and individuals. By the time the Wild West shows had captured the American imagination, Cody’s own past characterization of Native Americans as “former foes, present friends” proved to be an effective marketing tool: the posters that celebrate his life story tend to gloss over the genocide and focus on the expert rider, the sharpshooter and the enlightened preservationist.

“Jas. H. Wallick’s New Bandit King, Rescuing the Drowning Girl from the Rapids” by Strobridge Lithograph Company, date unknown. Lithograph, 30-3/8 by 40¼ inches. Gift of Harry T. Peters Jr, Natalie Peters and Natalie Webster.

Left unaddressed so far in this conversation about the proliferation, exploitation and disarmament of fears attached to the West is the fact that these fears are in every way attached to powerful ideas about masculinity. Rogers acknowledged as much when he confessed that, in organizing the show, he was looking for something “that would appeal to men,” an elusive museum visitor demographic. As a rule, what is on view here are male heroics, male villainy and male anxieties. In a different exhibition, this might seem exclusionary, but in the context of cowboy culture it seems not only unavoidable but also a legitimately relevant area of inquiry, given the wave of similar anxieties that are playing out in American culture today.

Even so, there are a handful of alternative perspectives in the exhibition. While Rogers laments that he was not able to secure an Annie Oakley poster for the show – Oakley being one of the more famous sharpshooters associated with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West shows – there is one of Princess Wenona, “the champion Indian girl rifle shot.” She appears on a poster for 101 Ranch, riding sidesaddle on her painted pony, smiling as she levels her rifle at a target. “They always portrayed themselves as very demure women,” Rogers muses about Oakley and Wenona, “and here they are using this tool that was associated with male activities – and showing men up.” Such are the contradictions – and challenges – engendered with a viewing of Shelburne Museum’s “Playing Cowboy.”

Shelburne Museum is at 6000 Shelburne Road. For information, www.shelburnemuseum.org or 802-985-3346.

.jpg)