Porringer with keyhole handle, marked by shop of Elias Pelletreau with stamp Mark 4; made by John Pelletreau (1755–1822), 1802. Engraved on handle obverse in block letters “JLG/1802” for John Lyon Gardiner (1770–1816). Silver; height 2 inches, length 7½ inches. Courtesy of Suffolk County Parks, Division of Historic Services. Photo Glenn Castellano.

By Laura Beach

STONY BROOK, N.Y. – Dean F. Failey, the American decorative arts authority who died in 2015 after a long affiliation with Christie’s, spent much of his life on the road securing the next great treasure for auction. But like Elias Pelletreau (1726-1810), the New York silversmith who apprenticed in Manhattan with the French Huguenot master Simeon Soumaine (baptized 1685-circa 1750) before returning to Southampton, N.Y., Failey never really left his native Long Island. From the beginning of his career to its end, Failey took a scholarly interest in the area’s craftsmen.

In a gesture of affection and esteem, Failey’s colleagues have picked up where he left off with his study of Pelletreau, guiding his research to fruition in the exhibition “Elias Pelletreau: Long Island Silversmith and Entrepreneur,” on view at Long Island Museum through December 30. Deborah Dependahl Waters, a former Museum of the City of New York curator and Failey’s Winterthur classmate, served as the show’s guest curator and a contributor to its accompanying publication, Elias Pelletreau: Long Island Silversmith and Entrepreneur, 1726-1810. The volume published by Preservation Long Island (PLI) builds on Failey’s work with additional material supplied by Jennifer L. Anderson, who served as editor; David L. Barquist; Robert B. MacKay and Charles F. Hummel. Championed by Failey’s wife, Marie, the two-pronged project was in part underwritten by the Decorative Arts Trust, on whose board Failey served and for whom its Failey Fund, supporting noteworthy research, exhibition and publication projects, is named; the Robert David Lion Gardiner Foundation, named for the heir to Gardiner’s Island, Robert D.L. Gardiner (1911-2004), a longtime Failey acquaintance; and Paul Guarner, a collector of New York silver with a focused interest in Pelletreau.

“Many people loved Dean and knew of his contributions. He was just a thoroughly decent and excellent scholar and so helpful to people in the field. The exhibition made perfect sense for us given the kinds of topics we cover and our focus on this region. It’s exciting to see it come to fruition,” says Joshua Ruff, Long Island Museum’s director of collections and interpretation.

Like so many chapters in the study of American decorative arts, this one bears the imprint of collector Henry Francis du Pont (1880-1969), whose onetime summer residence, Chestertown House, is a Southampton landmark. Thanks to funding from du Pont, the Pelletreau Silver Shop, restored between 1960 and 1966 by architect Robert L. Raley for the Southampton Colonial Society, still stands on Main Street. Du Pont acquired several pieces of Pelletreau silver for seasonal display at the shop, whose perpetuity he ensured through endowment.

“In effect, Dean continued Mr du Pont’s efforts to assure the reputation of Elias Pelletreau as Long Island’s most successful Eighteenth Century silversmith,” Winterthur curator emeritus and adjunct professor Charles F. Hummel writes in the catalog’s foreword. In the early 1970s, Hummel advised Failey on his master’s thesis, a 190-page study of Pelletreau. While illustrated with only eight silver objects by Pelletreau, Failey’s research compiled nearly 400 names listed in the silversmith’s accounts. Failey subsequently included the silversmith in his expansive catalog Long Island Is My Nation: The Decorative Arts & Craftsmen, 1640-1830, which accompanied a namesake exhibition, organized by PLI, then known as the Society for the Preservation of Long Island Antiquities (SPLIA), at Long Island Museum in 1976.

In semi-retirement, Failey returned to Pelletreau with an eye toward organizing an exhibition on the rural craftsman who was the contemporary of Boston’s Paul Revere and New York’s Myer Myers. In 2014, Failey, who had been working on the project with independent curator Jeannine Falino, visited Alexandra Parsons Wolfe. PLI’s executive director recalls, “Dean had an infectious way of drawing his listeners into a story through objects. By the time he was through with me, I too had become enamored of Elias Pelletreau.”

As book and exhibition recount, Pelletreau – like Soumaine, of French Huguenot descent – began his career in Manhattan in the 1740s. Sometime after 1750 he returned to Southampton, where he made, among other items, teapots, pepper boxes, porringers, tankards and jewelry for the Floyds, Gardiners, Jones, Hewletts, Smiths and other prominent eastern Long Island families. He moved to Connecticut – first to Salmon Brook (now Granby) and then Saybrook – during the Revolution, returning to Southampton in 1782. He died there in 1810, having relinquished most of his business to his sons during the 1790s.

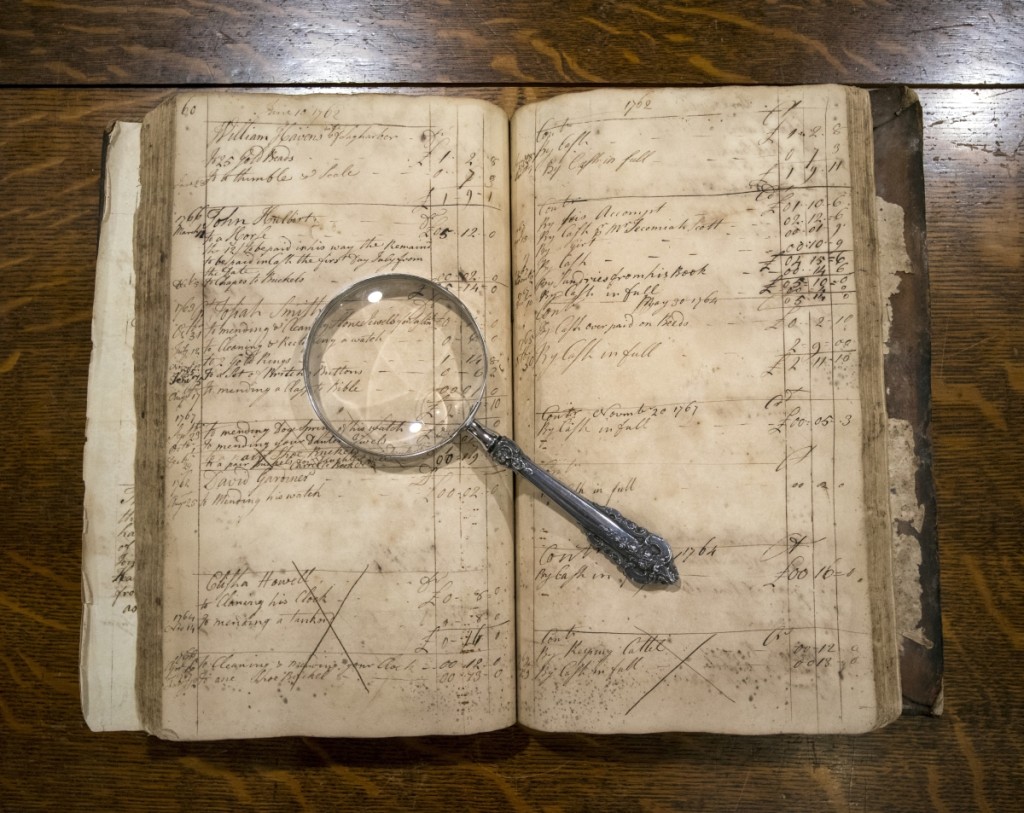

Anderson writes that Pelletreau’s account books were at first glance “an impenetrable thicket of names, dates and lists of objects.” Research was further complicated by the fact that at least 190 pages of account-book records from the 1750s have never been found. Beyond that, no diary and few letters survive, says Anderson, to “reveal his personal thoughts or feelings about his work, family or community.”

Waters reviewed lists compiled by Failey and Falino and worked with museum staff to track down marked Pelletreau objects and secure them for the exhibition, whose extensive list of lenders confirms wide appreciation for Pelletreau. Waters’ hunt turned up new records at Yale’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library and at the Southampton History Museum that deepened her understanding of the commercial activities of Pelletreau’s sons, Elias Jr and John. She also resolved longstanding confusion about two Pelletreau grandchildren, determining that it was Maltby Pelletreau (1791-1846), known for his role in coining commemorative medals for the Grand Canal Celebration in 1826, who carried on the family silversmithing tradition in Manhattan between 1813 and around 1840. Earlier researchers confused Maltby with his cousin, William Smith Pelletreau (1786-1842).

The team oversaw the installation of roughly 170 objects that, taken together, explore Pelletreau’s artistic development and commercial success, pairing examples of his silver with furniture, paintings, drawings, maps and tools to evoke the craftsman’s milieu and patronage network. Of note is a simulated silversmith’s workshop, with tools lent by silversmith Bernard Bernstein of New York City, who is represented in the collections of the Brooklyn Museum, the Museum of Arts and Design and the New-York Historical Society. Bernstein taught at New York’s 92nd Street Y Metalsmithing Program, with a specialty in Judaica.

Account Book No. 2, kept by Elias Pelletreau, circa 1761–65, 1780–82. Leather binding and laid paper; 13 by 8½ by 1-1/8 inches. Long Island Collection, East Hampton Library. Photo Gina Piastuck.

The first show devoted to Pelletreau since one organized by the Brooklyn Museum in 1959 ranges from the earliest known Elias Pelletreau silver – a pair of communion beakers, now in the collection of Paul Guarner, that the artist made for the Church of Christ in Groton, Conn., to fulfill a 1748 gift by the estate of Elihu Avery (1707-1748) – to a porringer with keyhole-handle created for John Lyon Gardiner (1770-1816) in 1802, probably by John Pelletreau.

“One of the most important and interesting pieces is a circa 1760-90 inverted pyriform or double-bellied form teapot, now in the collection of the Newark Museum, that descended in the Pelletreau family,” says Waters, calling attention to the engraved initials “EP,” likely for Elias Pelletreau, and “J.P.A,” for Jane Pelletreau Ashley Bates (1808-1885), great-granddaughter of the silversmith. The teapot surfaced at Pook & Pook before it was acquired by New York antiquary S.J. Shrubsole.

“There was one known Pelletreau teapot, at the Minneapolis Institute of Art, when Dean first did his work. Now we know of five,” says Waters, who brought together four Pelletreau teapots for the display. Organizers were unable to locate the fifth, a privately owned teapot that turned up about 20 years ago at a taping of Antiques Roadshow in Portland, Ore.

While the teapots dazzle, it is canns and flat-top tankards that Pelletreau’s customers more often ordered. The silversmith’s most common form was the porringer, which he made with three types of handles: keyhole, trefoil and modified trefoil.

Questions about authenticity linger. “That was a subject Dean had begun to explore while doing research in the 1970s. He and Marie were given a suspect spoon as a wedding gift. Dean realized that a group of things said to have belonged to William Walton were probably not right. We’ve illustrated the mark in the catalog,” says Waters. Janice Carlson and Donald L. Fennimore further explored the subject in “The Fakes,” published in The Stevens Indicator (Stevens Institute of Technology Alumni Association, Hoboken, N.J., Winter 1983). The collection under review was formed by Arthur Lenssen (1874-1968).

The gregarious Failey would have relished two collegial gatherings planned in conjunction with the show. On October 27, Long Island Museum is hosting a daylong symposium exploring Pelletreau’s life and work. Speakers will include Waters, Anderson and Barquist. The French-born jeweler and silversmith Eric Messin, artist-in-residence at the Pelletreau Silver Shop, will demonstrate metal hammering. For details, go to www.longislandmuseum.org.

Left, flattop tankard marked by Simeon Soumaine (baptized 1685–circa 1750), New York City, 1730–1750. Engraved on handle with block initials “S/D*H,” for Daniel 2d (1690/1–1763) and Hannah Brewster Smith (1697/8 –1761); engraved on base in later script “David & Hannah Smith/Smithtown, Long Island/1691–1763.” Silver; height 6-5/8 inches. Preservation Long Island, gift of Miss Alice Lawrence. Right, flattop tankard marked by Elias Pelletreau, 1750–1776. Engraved with block initials “I/I*M” on base. Silver; height 7½ inches. Preservation Long Island, gift of Howard C. Sherwood, 957.608. Photo Glenn Castellano. The Soumaine tankard came down in the family of General John Smith (1752–1816), a US Representative and Senator, the grandson of Daniel 2d and Hannah Brewster Smith, to the donor.

On November 30, the Decorative Arts Trust is pairing a tour of “Elias Pelletreau: Long Island Silversmith and Entrepreneur” with a visit to the PLI-maintained Sherwood-Jayne Farm. The property features a 1730s saltbox house restored by Colonial Revival architect Joseph Everett Chandler for PLI founder Howard C. Sherwood. For details, go to www.decorativeartstrust.org.

Organized by Ruff, “Shaping Silver: Contemporary Metalsmithing,” a companion exhibit on view at Long Island Museum through December 30, features work by Michele Oka Doner, Michael Izrael Galmer, Brian Weissman and Erin Shay Daily, Wendy Yothers, Patricia Madeja and Messin.

Dean Failey’s dedication to the American decorative arts and his affection for those who shared his passion are repaid many times over by this sumptuous festschrift. As Hummel puts it, “Dean’s groundbreaking investigation of the archives and extant objects of Elias Pelletreau will inspire greater awareness of this artisan who deserves a prominent place in the history of Long Island’s decorative arts. With gratitude and appreciation, we acknowledge Dean F. Failey for his significant and indelible contributions to our understanding of early American craftsmanship.”

The Long Island Museum, a Smithsonian Affiliate dedicated to the study of the region’s history and culture, is at 1200 Route 25A. For additional information, 631-751-0066 or www.longislandmuseum.org. For more on Preservation Long Island, go to www.splia.org.