“History is Painted by the Victors” by Kent Monkman (Fisher River Band and Swampy Cree, b 1965), 2013. Acrylic on canvas, height 72 by width 113 by depth 1½ inches. Denver Art Museum. ©Kent Monkman. Photo courtesy Denver Art Museum. “Art for a New Understanding: Native Voices, 1950s to Now,” AIAI Museum of Contemporary Native Arts.

By Laura Beach

MONTREAL, WASHINGTON, BOSTON, NEW YORK AND SANTA FE – Over the summer, I had the good fortune to see “Shame and Prejudice: A Story of Resilience,” an exhibition now making its leisurely way through Canada. The monumental show features paintings, prints and mixed-media assemblages by Kent Monkman (b 1965), a contemporary Canadian artist of Cree ancestry who turns the tropes of Nineteenth Century academic painting and printmaking upside down in his retelling of North American history through the eyes of First Nations people. The sheer scale of Monkman’s modern history paintings, along with his ironic manipulation of familiar imagery, makes for compelling viewing.

Monkman is part of a broader movement in the United States and Canada aimed at setting the historical record straight and charting a new course for the collection, interpretation and display of Native American, Metis and Inuit art. The moment is pivotal, as the following summaries suggest. The challenge going forward will be to honor Native art as a distinct tradition while acknowledging its central place in an American story for which there is no single perspective.

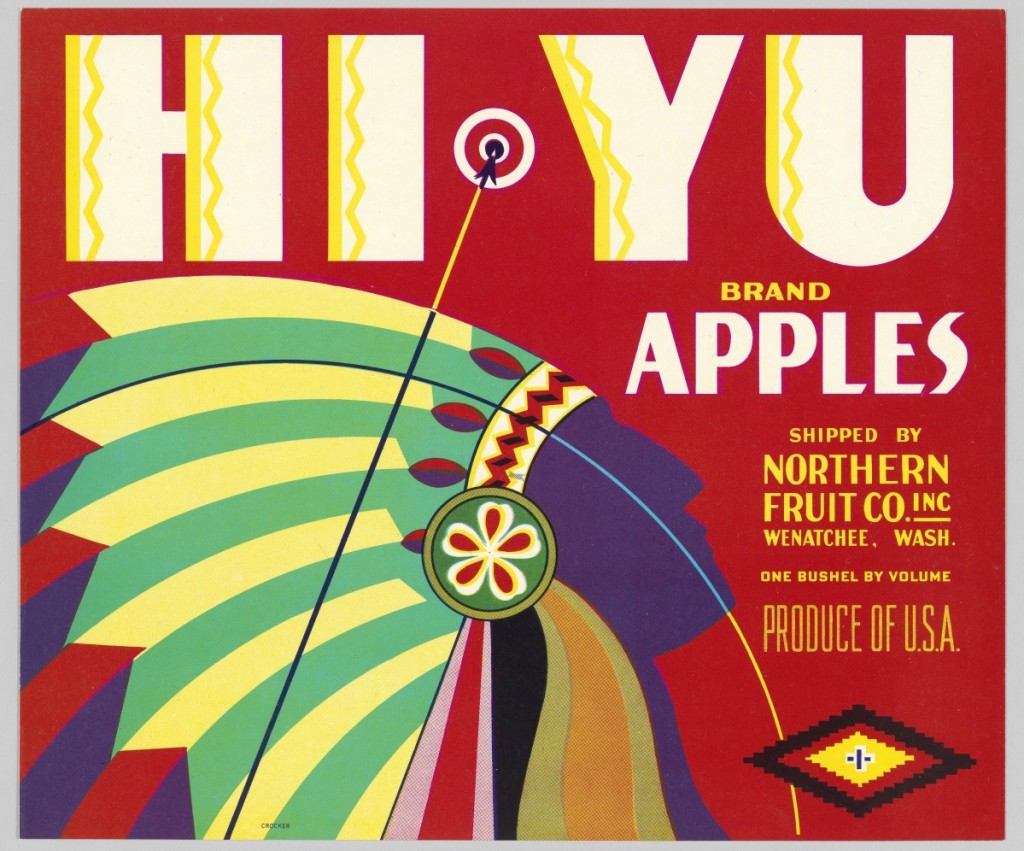

Before they were replaced by cardboard boxes in the 1960s, wooden boxes bearing colorful designs were used to ship fruit and vegetables. Often the labels featured Native American motifs. Hi Yu was the name of a brand of apples shipped from Wenatchee, Wash. “Americans,” National Museum of the American Indian, Washington DC.

‘Americans’

Writing about “Americans” not long after it opened at the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington DC in January 2018, New Yorker magazine critic Peter Schjeldahl observed that the exhibition was “keyed to the ubiquity of Native Americans in popular culture.” Indeed, this major presentation arrays all manner of Indian-themed artifacts, from movie posters, toys and tobacco advertising to sports team memorabilia. Co-curated by Paul Chaat Smith (Comanche), a contributor to Art for a New Understanding: Native Voices, 1950s to Now (Crystal Bridges/University of Arkansas Press), discussed below, “Americans” is fierce but also affectionate, using humor to draw attention to demeaning and dismissive stereotypes. “The curator’s approach,” Schjeldahl writes, “lets identity and politics float a little free of each other, allowing wisdom to seep in. The show attempts it by parading crudely exaggerated understandings of Native Americans, ossified in kitsch, to awaken reactive senses of complicated, deep, living truths.”

“Americans” remains on view through 2022.

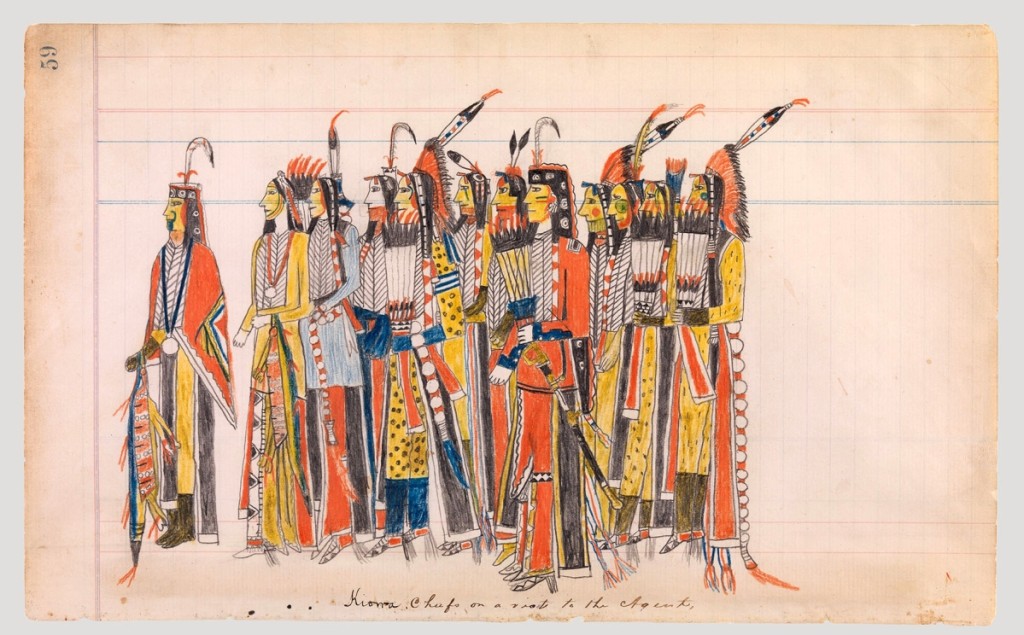

“Kiowa Chiefs on a Visit to the Agent,” attributed to Julian Scott, Ledger Artist B (Kiowa), Oklahoma, circa 1880. Pencil, colored pencil and ink on paper, 7½ by 12 inches. Promised gift of Charles and Valerie Diker. “Art of Native America: The Charles and Valerie Diker Collection,” Metropolitan Museum of Art.

‘Art of Native America: The Diker Collection’

On view through October 6, 2019, “Art of Native America: The Charles and Valerie Diker Collection” represents a preliminary step by the Metropolitan Museum of Art to address a century-long oversight common among most of America’s top art museums. The vehicle for this quasi-revisionist view is a collection – variously donated, promised and loaned to the Met – of Native American art assembled over the past 45 years by collectors exquisitely attuned to aesthetics. It was not until 2016 that three Diker pieces – a Haudenosaunee pouch, a Pomo basket and a jar by Maria and Julián Martínez of San Ildefonso Pueblo – were included in the American Wing, whose staff now acknowledges the need to tell, in the words of show organizer Sylvia Yount, the “entangled histories of contact and colonialization from both Native and Euro-American perspectives.”

Essential reading, the show’s accompanying catalog conveys the complexity and nuance of the issues involved. Yount, the Lawrence A. Fleischman curator in charge of the American Wing, writes at length about the history of the American Wing, founded in 1924, and the place Native American art held in the imagination of its founders and the wider public, which encountered Native art in department stores, railway hotels and at the great expositions of the day.

Yount’s essay pairs beautifully with another by Gaylord Torrence. As guest curator of the Met’s Diker show, the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art curator juxtaposes his understanding of Native sensibility with the Anglo view offered by Yount. He describes his formative meeting more than 35 years ago with a Meskwaki man who invited him to see artifacts passed down in the man’s family. As Torrence recalls, “I asked whether he thought the spoon dated from the early 1800s, the early 1850s, the 1870s or later. He did not respond immediately but then asked, ‘What difference does it make?’ It was clear that my question had little meaning for him.” The curator concludes, “I have never forgotten this encounter, which awakened me to the many ways one can look at and think about Native American art – analytical and emotional, academic and experiential, material and spiritual – some perspectives from outside various belief systems, others from inside.”

Summing up, Ned Blackhawk (Western Shoshone), author of the catalog’s third essay and a professor of history and American studies at Yale University, says, “The longstanding curatorial practice of designating arts as ‘primitive’ or ‘ethnographic’ or ‘nonwestern’ has limited our capacity to see a broader, more shared community, in my mind. We often think of these objects as an untainted window into a world of premodern life, but they are products of a colonial encounter.”

A core group of works from the Diker Collection will remain on view in the American Wing’s Erving and Joyce Wolf Gallery. Light-sensitive material will be rotated annually. The Met continues to explore ways of regularly juxtaposing works by Americans of different cultural backgrounds.

Olla (water jar), Zuni Pueblo, 1820–40. Earthenware with white and black slip paint, height 11 by width 13-9/16 inches. Gift of Mrs George A. Goddard. “Collecting Stories: Native American Art,” Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

‘Collecting Stories: Native American Art’

The thoughtful exhibition “Collecting Stories: Native American Art,” at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, through March 10, avoids the absurdity of presenting Native art as a monolithic whole by focusing instead on its meaning to the worldly, education-minded Bostonians who collected it in the late Nineteenth and early Twentieth Centuries. “It was a way to create a framework for the objects while also interrogating the museum’s own history,” explains Layla Bermeo, who organized the presentation with fellow Art of the Americas curator Dennis Carr.

The show emphasizes artifacts that entered the collection in the four decades following the MFA’s debut on July 4, 1876, a week after the Battle of Little Bighorn. It was not until the 1970s that the MFA, largely through the initiative of curator Jonathan Fairbanks, then head of the MFA’s department of American decorative arts and sculpture, renewed its interest in Native art.

Works on view range from a Northern Plains warrior’s headpiece collected by Reverend Herbert Probert during a missionizing trip to Wyoming in the early 1880s to a Zuni olla given by a trader to Jane Loring Gray, sister of MFA director General Charles Loring, himself a collector of Southwestern pottery and textiles. Ahead of his time, Denman Waldo Ross, a Harvard professor of art and design, admired the formal beauty of the Navajo wearing blanket he presented to the MFA in 1902, long before Modernists saw the formal possibilities of Native art.

The MFA has been at the forefront of the desegregation movement afoot in the museum world since replacing its conventional American galleries with the 53-gallery Art of the Americas wing in 2010. As Carr observes, “It would be impossible to tell the story of America or American art without the inclusion of Native art. The mission we are embarking on now is to show it not only in its own space, but also fully integrated into the story of American art of all periods.” Of Native art in the MFA collection, Bermeo adds, “These objects have had many lives and played many roles. Often the best way to bring those stories out is to consult people who have different forms of knowledge or have different training than ourselves.”

“Collecting Stories: Native American Art” is the first of three exhibitions supported by the Luce Foundation that look at underserved areas of the MFA’s collection.

“Dance of the Heyoka” by Oscar Howe (Yanktonai Dakota, 1915–1983), circa 1954. Watercolor on paper, height 20¼ by width 26¼ inches. Philbrook Museum of Art, Tulsa, Okla. ©2018 By permission of the Oscar Howe Family. “Art for a New Understanding: Native Voices, 1950s to Now,” AIAI Museum of Contemporary Native Arts.

‘Art for a New Understanding: Native Voices, 1950s to Now’

Organized by Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art and continuing at the Institute of American Indian Arts’ Museum of Contemporary Native Arts (IAIA MoCNA) in Santa Fe, through July 19, “Art for a New Understanding: Native Voices, 1950s to Now” offers fresh perspectives in place of old biases and misconceptions. To tell the tale, co-curators Mindy Besaw of Crystal Bridges, independent curator and writer Candice Hopkins (Tlingit, citizen of Carcross/Tagish First Nation) and Manuela Well-Off-Man of IAIA MoCNA selected roughly 80 works made between the 1950s and the present by more than 40 American and Canadian artists of indigenous descent.

The chronological array begins with creations by trailblazers such as Lloyd Kiva New (1916-2002), who co-founded the IAIA in 1962 with funding from the Bureau of Indian Affairs; Fritz Scholder (1937-2005); T.C. Cannon (1946-1978) and Kay WalkingStick (b 1935). It proceeds to the latest international stars, Kent Monkman and Cannupa Hanska Luger (b 1979) among them. The show draws its title from a sculpture of the same name by the Northwest Coast artist Brian Jungen (b 1970), who fashioned a mask out of Nike sneakers in an oblique commentary on the commodification of Native art.

In their catalog essay, the curators describe the long, if subordinate, presence of Native creativity in the mainstream art world. Perceptions began to change around 1958, when Oscar Howe (Yanktonai Dakota, 1915-1983) protested the rejection of one of his paintings from the prestigious Philbrook Annual in Oklahoma. The Rockefeller Foundation responded to the need for change by organizing the conference “New Directions in Indian Art” the following year. The conference’s 31 participants included New, Scholder and the ever progressive MoMA director Rene d’Harnoncourt. As a review of the IAIA program makes clear, today’s Native artists are an increasingly diverse group working in mediums ranging from traditional painting and sculpture to avant-garde performance, film and video.

Speaking from Santa Fe, Well-Off-Man said she considers the current crop of exhibitions the consequence of decades of hard work by those who have gone before her and notes the eye-opening participation of Native artists in recent international expositions such as the Venice Biennale and documenta, mounted in Kassel, Germany every five years.

Challenges remain, Well-Off-Man says. “Visitors to the IAIA MoCNA are often being confronted with contemporary Native art for the first time, so it’s really important to provide the context. Additionally, we are just one of a few institutions that feature contemporary Native art on a regular basis. Providing more exhibition spaces for our talented artists is key. Another major challenge is that there are not enough Native curators and art historians who can teach contemporary Native art in colleges and universities.”

Following its close at IAIA MoCNA, “Art for a New Understanding” travels to the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University in North Carolina and the Memphis Brooks Museum of Art in Tennessee.

In Conclusion

“Shame and Prejudice: A Story of Resilience” is on view at the McCord Museum from February 8 to May 5. The McCord Museum is at 690 Sherbrooke Street West in Montreal. For information, 514-861-6701 or www.musee-mccord.qc.ca/en.

“Americans” is on view through 2022. The National Museum of the American Indian, Washington DC, is on the National Mall at Fourth Street and Independence Avenue, SW. For information, 202-633-1000 or www.americanindian.si.edu.

“Art of Native America: The Charles and Valerie Diker Collection” is on view through October 6 a the Metropolitan Museum of Art is at 1000 Fifth Avenue in New York City. For information, 212-535-7710 or www.metmuseum.org.

“Collecting Stories: Native American Art” is on view through March 10 at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, is at Avenue of the Arts, 465 Huntington Avenue. For information, 617-267-9300 or www.mfa.org.

“Art for a New Understanding: Native Voices, 1950s to Now” is on view through July 19. The IAIA Museum of Contemporary Native Arts is at 108 Cathedral Place in Santa Fe. For information, 888-922-4242.