“Peach Packing, Spartanburg County” by Wenonah Day Bell (1890–1981), 1938. Oil on canvas, 38-1/8 by 48-1/8 inches.

By Karla Klein Albertson

HUNTINGTON, W.Va. – In recent years, the movement to acknowledge the undeniably equal importance of women’s contributions to the creative arts has benefited from scholarly research. Special exhibitions focused on artists from a particular place or period strive to make up for the lost time the artworks languished from neglect. Sotheby’s January sale, “The Female Triumphant,” proved highly successful with an offering of 21 works by 14 pre-Modern era female artists from the Sixteenth to Nineteenth Century. On view at the Belvedere Museum in Vienna through May 19, “City of Women: Female Artists in Vienna from 1900 to 1938” puts on display rediscovered works by dozens of women artists who played a role in Viennese Modernism.

So, it is not surprising that in the United States, “Central to Their Lives: Southern Women Artists in The Johnson Collection” is touring the work of more than 30 significant female painters and sculptors whose output is represented in the South’s preeminent assemblage of regional art. The Johnson Collection, based in Spartanburg, S.C., was founded, funded and fueled with artworks by philanthropists George Dean Johnson Jr and his wife, Susan “Susu” Phifer Johnson. The current show is the third in a series of projects that combine exhibition tours to multiple museums, a permanent reference book published in connection with the University of South Carolina Press, and a substantial expansion of the institution’s online database. Not only does the book contain scholarly essays and biographical sketches of all the featured artists, an appendix presents “A Directory of Southern Women Artists” listing more than two thousand additional names with geographical locations and dates.

Lynne Blackman, director of communications at the collection, said in a recent interview with Antiques and The Arts Weekly: “Planning for this particular exhibition began four or five years ago, and it was coordinated between the exhibition staff and the collection’s founding director, David Henderson, who has a remarkable breadth of knowledge about southern artists. The inspiration and instigation would really be credited to one of the collection’s owners, Susu Johnson. We had within our holdings several key areas of specific interest, both intellectually and as a focus for acquisitions, and women artists were on that list. Susu is a graduate of a women’s college, and she was an early feminist and a proponent of women’s opportunities. She had always prioritized the work of women artists as important to the story of southern art and American art.”

Susanna Johnson Shannon, the Johnsons’ daughter and curatorial advisor to the family collection, stressed in her catalog introduction that creativity comes naturally to our species but is expressed by women in a challenging environment: “…women gifted with the instinct to ‘make art’ have had to scrape and squeeze and salvage the space – literal, temporal and emotional – to pursue it…. Whether constrained by family responsibilities, societal expectations or a narrow menu of professional tracks, women have perpetually needed a sustained and sturdy sense of purpose when it comes to composing, studying and selling art.” Just as Artemisia Gentileschi fought to enter the male-dominated field of painting in Seventeenth Century Italy, southern women artists in the late Nineteenth and early Twentieth Century had to overcome cringe-worthy regional stereotypes about female behavior and suitable occupations. The obstacles faced by each individual are outlined in the catalog biographies contributed by a roster of art historians chosen for their expertise on each artist.

Anne Wilson Goldthwaite (1869-1944), for example, was the daughter of a Confederate officer, raised in conservative Montgomery, Ala. Like many women artists from the South and elsewhere, she traveled to New York and then Paris to pursue her career, eventually settling down to a job teaching at the Art Students League. Although she studied alongside modernists, she never abandoned her grasp of realism and enjoyed a reputation for portraiture. Her telling statement from a 1934 radio interview is quoted in her biographical entry. Speaking of the status of women artists at that time, she noted that “the best praise that women have been able to command until now is to have it said that she paints like a man. But that women have a valid place as women artists is both obvious and logical…. We want to speak to…an audience that asks simply – is it good, not -was it done by a woman.”

Daniel Belasco in his catalog essay “Eyes Wide Open: Modernist Women Artists in the South” follows a reference to Goldthwaite’s words with a quote by celebrated New Orleans painter Ida Rittenberg Kohlmeyer (1912-1997) from a catalog introduction she wrote in 1972, almost four decades later: “With tensions relaxing for women artists, one quickly forgets the Olympian efforts which were required to sustain them against society’s unrelenting demands, lack of encouragement and opportunity, unfair competitive treatment, persistent fall-out from male chauvinism plus the energy, dedication and zeal implicit in a creative life.” In other words, plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose.

Kohlmeyer knew whereof she spoke. A 1933 graduate of Newcomb College for women, she had married and raised children before emerging as an abstract expressionist with a penchant for colorful symbolism painted boldly on large canvases. The oil painting on view in the exhibition, “Fantasy No. 2” from 1964, is a relatively early work; the 1970s and 1980s were her prolific period. Of all the women artists in the exhibition, Kohlmeyer currently enjoys the greatest posthumous success in the marketplace. When her canvases and sculptures are offered in New Orleans, they regularly merit five-figure prices, and at Neal Auction Company’s Louisiana Purchase sale in November 2015, “Cluster #1” from 1973 sold for a record $110,250.

The most optimistic scholars hope for a future when artists would be considered only for their inherent talent, not separated into a special box by sex or ethnicity. An excellent example from this exhibition would be Augusta Savage (1892-1962), a Twentieth Century sculptor as accomplished as any of her contemporaries. Her biography may emphasize that she was an African American southern woman in the field, but that merely acknowledges the difficult journey she undertook from her birth into a poor Florida family to the studios of New York and Paris. The Dixon Gallery and Gardens in Memphis is one of the 2019 venues for the exhibition, and curator Julie Pierotti wrote the entry on Savage. The work representing Savage is “Gamin,” circa 1930, the sensitive bust of a street urchin, which brought the sculptor international recognition for her abilities.

In an interview, Pierotti said, “When they asked me to contribute to the catalog, I was flattered. We have a version of ‘Gamin’ in our collection, and we did an exhibition on Savage in 2014. I also wrote the entry on painter Adele Lemm (1897-1977); she made her home and career in Memphis. We have an excellent relationship with the Johnson collection. When we opened our galleries back up after renovations in 2015, our first show was ‘Scenic Impressions’ and that was a truly positive exhibition for us on a number of levels. First of all, the paintings in it were beautiful and our visitors really loved it, but also it was a great opportunity to work with them – they were very supportive.”

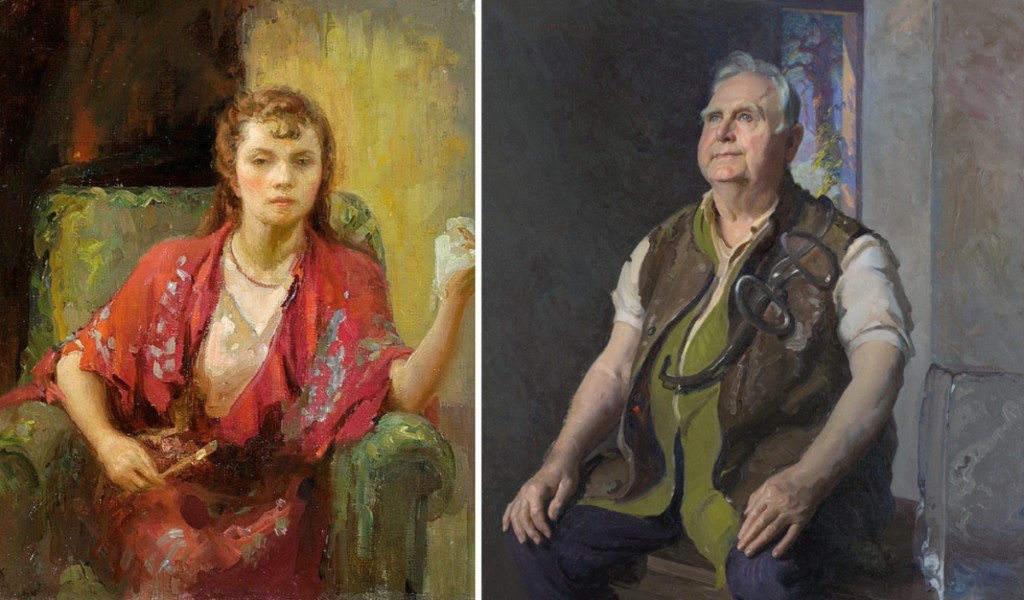

A major contributor to the exhibition and the accompanying volume was independent scholar Martha R. Severens, former curator of the Greenville County (S.C.) Museum of Art and Gibbes Museum of Art in Charleston, S.C. Her essay – “‘The Pedestal has Crashed:’ Issues Facing Women Artists in the South” – opens the catalog. She explained the title in the first paragraph: “…the pedestal image had double meaning. Long the object of the male gaze – especially when undraped – women had provided artistic fodder since ancient times. Thus it was particularly hard for women artists to assert themselves in an environment dominated by men – to move, as it were, to a place behind the easel instead of in front of it.” In conversation, she continued, “Women artists will have arrived when they are fully integrated. I think the exhibition will open people’s eyes to the purview of women artists. I think this project is a foundation which will help people see these artists in a bigger context, that transcends the ghetto of being women artists in the South.”

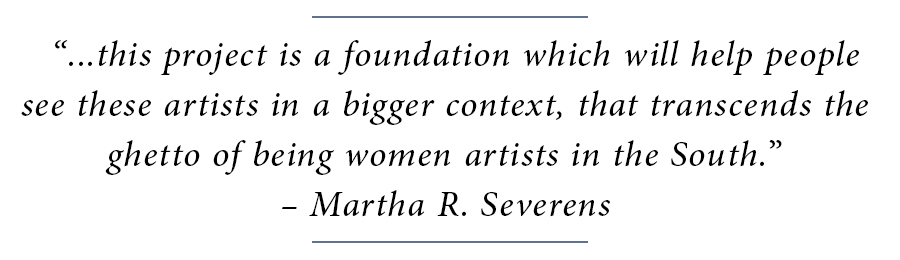

Every woman in the exhibition is represented by a photograph or self-portrait in the catalog. Thus “Time Out,” right, a 1938–39 portrait of an iceman with his tongs by Gladys Nelson Smith (1890–1939), can be compared to her personal vision of herself.

On its extended tour of institutions, “Central to Their Lives” is now on view at the Huntington Museum of Art in West Virginia through June 30 and heads next to the Dixon Gallery and Gardens in Memphis, July 28-October 13. Future venues include the Gibbes Museum of Art, Charleston, S.C.; the Cummer Museum of Art and Gardens, Jacksonville, Fla.; and the Taubman Museum of Art, Roanoke, Va.

Lynne Blackman, who attended the 2018 exhibition openings at the museums in Georgia and Mississippi, said, “It was like a reunion or homecoming in a way, because we’re all deeply familiar with each of the exhibits. I enjoyed seeing the way the works interacted – not just on a planning table or in a book – but on display beside each other. Every institution puts its own mark on the exhibition. We appreciate the expertise each partner venue brings to the project. They know their audience and respond to what that audience might most enjoy. They bring their own curatorial framework to it, and we learn so much that way.”

The Huntington Museum of Art is at 2033 McCoy Road. For information, 304-529-2701 or www.hmoa.org.