“Shining Sunbeam” by John Gould, Family of Humming-Birds, plate 179, 1849–1861. Hand colored lithograph with gold leaf, 21½ by 14¾ inches.

By Karla Klein Albertson

CHICAGO – While American collectors are familiar with the oft-auctioned prints of John James Audubon (1785-1851), they are less knowledgeable about the illustrated publications of British ornithologist John Gould (1804-1881). Among his best-known works are sweeping surveys such as The Birds of Europe, completed in 1837, The Birds of Australia (1840-1848), and The Birds of Great Britain (1862-1873). Gould, however, had an incredibly focused passion for hummingbirds and sought to capture the infinite variety of those tiny winged creatures that never sit still. The result of that interest was A Monograph of the Trochilidae, or Family of Humming-Birds, a five-volume publication issued in 25 parts between 1849 and 1861.

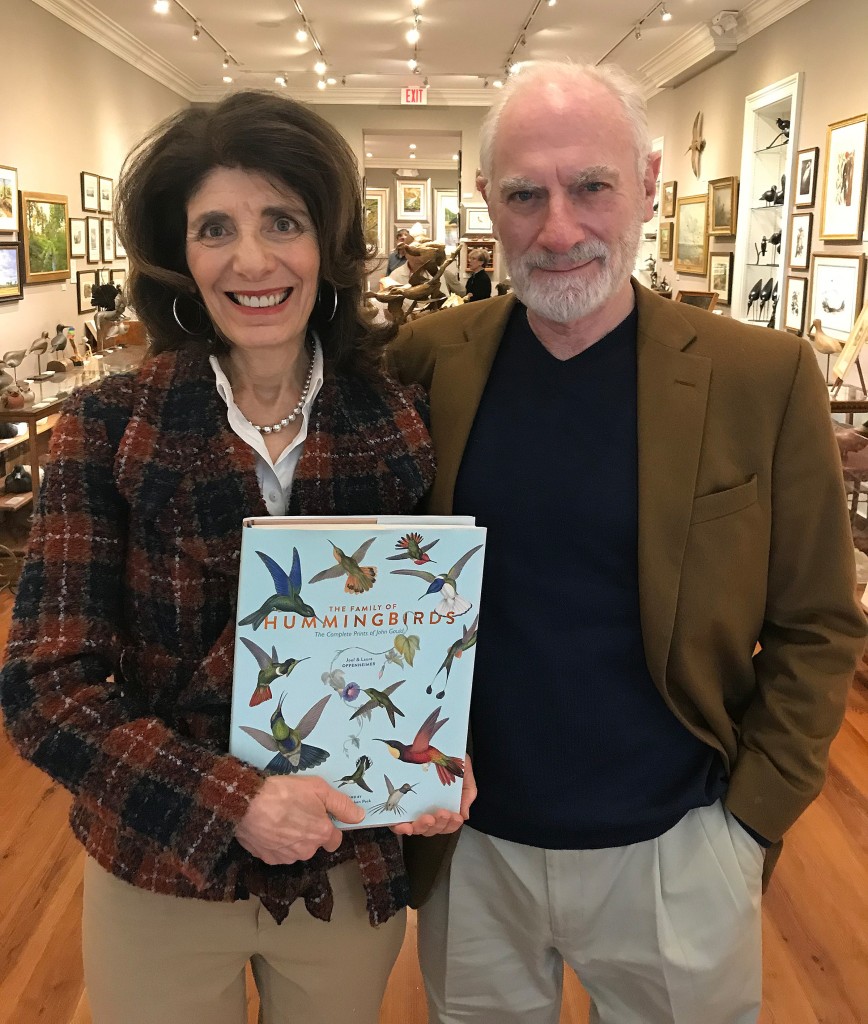

Reproductions of the 418 hand colored lithographs produced by the ornithologist are now available in The Family of Hummingbirds: The Complete Prints of John Gould, a reference published in 2018 by Rizzoli/Electa. The project was undertaken by Joel and Laura Oppenheimer, who own two galleries devoted to a wide range of natural history art from past centuries. The volume opens with her essay on “A Passion for Birds: The Life and Legacy of John Gould” and his on “The Production and Methods of Creating Family of Humming-Birds.” The publication answers important questions about Gould and his research: who was this Nineteenth Century student of ornithology, where did he acquire the specimens, and how was he able to reproduce drawings of them for his books?

In a conversation with Antiques and The Arts Weekly, Joel Oppenheimer explained that they had worked with editors at Rizzoli on a previous volume: “They would visit our gallery once in a while when they were in Chicago. We were talking over a several year period about the possibility of doing another publication. In the meantime, we had acquired this set of Gould’s hummingbirds, and they thought that would be a great book to do. The actual writing – we were working in earnest on it for about two years.

We are a private art gallery. Unlike a museum, we are in the business of selling art, so, of course, we wanted to promote the book and to sell Gould prints. But I think we do take a scholarly approach to the exhibitions we mount and have had some remarkable exhibitions over the years. This is our 50th year in the business and we’ve been specializing in natural history art for almost 30 years now.”

The author continued, “Gould had many accomplishments, but his work on hummingbirds ranks highly in terms of popularity because of the subject matter.” The introduction to the new book by Drexel University naturalist Robert McCracken Peck cites the acclaim given to Gould’s publication when it appeared in the mid-Nineteenth Century: “It represented a family of birds of remarkable grace and beauty that lived in exotic habitats unlikely to be seen even by collectors who were wealthy enough to afford the books Gould devoted to them. The public and press were dazzled by the hundreds of tiny hummingbird specimens Gould prepared and exhibited in a temporary structure in the Zoological Society Garden at Regents Park….” Gould’s show took place during the Great Exhibition of 1851 located in Hyde Park and continued until the end of 1852. Paying six pence a head, approximately 75,000 visitors – many in town for the exhibition – also visited the hummingbirds he had gathered.

In the era before widespread photography and film, such displays constituted the public’s first glimpse of birds and animals from distant regions of the world. In the field of research and publication in natural history, studies of flora had preceded those of fauna because of the difficulties of preserving specimens of animals and birds. In fact, Europeans had no knowledge of the existence of hummingbirds until they were first seen by French adventurers searching for gold in Brazil in 1558, and it was 1693 before the Royal Society published a proper description of the fleet-winged birds. Gould himself did not see a living example until an 1857 trip to America, where he observed a ruby-throated hummingbird at Bartram’s Gardens in Philadelphia and then viewed more birds on the wing in the gardens of the Capitol in Washington, DC.

Born in 1804 at Lyme Regis in Dorset, John Gould’s boyhood gave no hint of his future publishing path. As outlined in Laura Oppenheimer’s biographical chapter, he began life working alongside his father as a gardener. When the senior Gould was appointed in 1817 to a position on the grounds of Windsor Castle, young John became acquainted with nature on a grand scale, and he took a special interest in the fauna that inhabited it. He became especially skilled at taxidermy, which allowed naturalists to preserve specimens for study and gave artists a chance to capture minute details of form and color.

As her text stated, “Gould’s passion for birds was primary, and his expertise in taxidermy was proving to be more lucrative than his work as a gardener. In 1825 he moved to London to set up shop as a taxidermist. His adeptness at mounting skins in lifelike poses and his connections at Windsor proved advantageous.” The same year he preserved an avian specimen for King George IV. After winning a competition, he became the first curator and preserver at the new museum of the Zoological Society in London. There he became acquainted with leading naturalists who were returning from global journeys with collections of specimens. Although Gould had an innate aesthetic sense, a key element to his future career was acquired when he married Elizabeth Coxen (1804-1841), who was a talented artist.

They worked together on his first book, producing A Century of Birds from the Himalaya Mountains (1830-1833). The text continues, “Elizabeth illustrated Gould’s mounted specimens in graphite and watercolor, depicting 100 birds. She then transferred her illustrations onto lithographic stones.” When Charles Darwin returned from his second voyage, the Goulds entered into a project of identification and illustration with him. In 1838, the couple journeyed to faraway Australia to begin studying the birds of that region. They continued to work together until Elizabeth Gould died in 1841 after the birth of her eighth child. John then turned to other artists, such as H.C. Richter (1821-1902) who worked with him on the hummingbird volumes.

The production of natural history volumes in the Nineteenth Century was a complicated process, as Joel Oppenheimer noted, “You had the explorers, the people who were procuring the specimens, the ones who were analyzing them, and the ones who were making the pictures of them. Audubon was all of those in one. Gould was a terrific businessman and very ambitious, so as his popularity grew, he was able to employ other artists to do the work. He continued to make compositional drawings and sketches as instructions for the artists.” As can be seen from the illustrations, Gould exhibited particular skill in the composition and arrangement of the hummingbirds on each plate, where they are often shown in flight, extracting nectar from flora.

Joel and Laura Oppenheimer hold a copy of their newly released book, The Family of Hummingbirds: The Complete Prints of John Gould, published in 2018 by Rizzoli/Electa.

Oppenheimer’s chapter on production tackles the techniques of lithography, which was the method used for all of Gould’s plates. The process had only been discovered in the early decades of the century; Alois Senefelder (1771-1834) published A Complete Course of Lithography in 1818. The author pointed out, “We see the prints as antiques today, but in their time, these were very modern works of art. The artists were anxious to use the latest technology that had become available. As we progressed from wood engraving to copper plate engraving, eventually etching is created, and then the age of lithography and eventually chromolithography which was the final phase before photo-mechanical techniques were employed.”

In Gould’s time, the lithographic prints had to be hand colored, which created an extensive cottage industry for artists who did nothing but color illustration plates. Joel Oppenheimer went on, “It is a relatively recent phenomenon for the general public to have access to color images. Before the invention of chromolithography, it was a very special thing to own a book with color illustrations. Back then they had to create a method to achieve consistent coloring, because there would be teams of colorists. But you wouldn’t know it by looking at the finished product because the plates look like they were done by the same hand.” In a special section, the chapter discusses the ways in which Gould and his artists devised a method to reproduce the iridescent plumage found on hummingbirds.

Laura and Joel Oppenheimer both give credit to the Gould archives in the Ellis Collection at the Kenneth Spencer Research Library at the University of Kansas. Ralph Ellis assembled a vast collection of ornithological material which was given to the university after the collector’s death in 1945 and cataloged by Robert M. Mendel. They also drew upon the work or Dr Gordon Sauer who transcribed Gould’s handwritten correspondence and produced a proper chronology and bibliography for the Nineteenth Century English publisher.

In the final analysis, these prints transcend scholarly and historical considerations. They are complex art works displaying the lively compositions and exquisite coloring of the rare birds that inspired them.

The Joel Oppenheimer Gallery in Chicago sells natural history art prints and offers restoration and framing services. A second location, the Audubon Gallery, is on King Street in Charleston, S.C.

Learn more at www.audubonart.com.