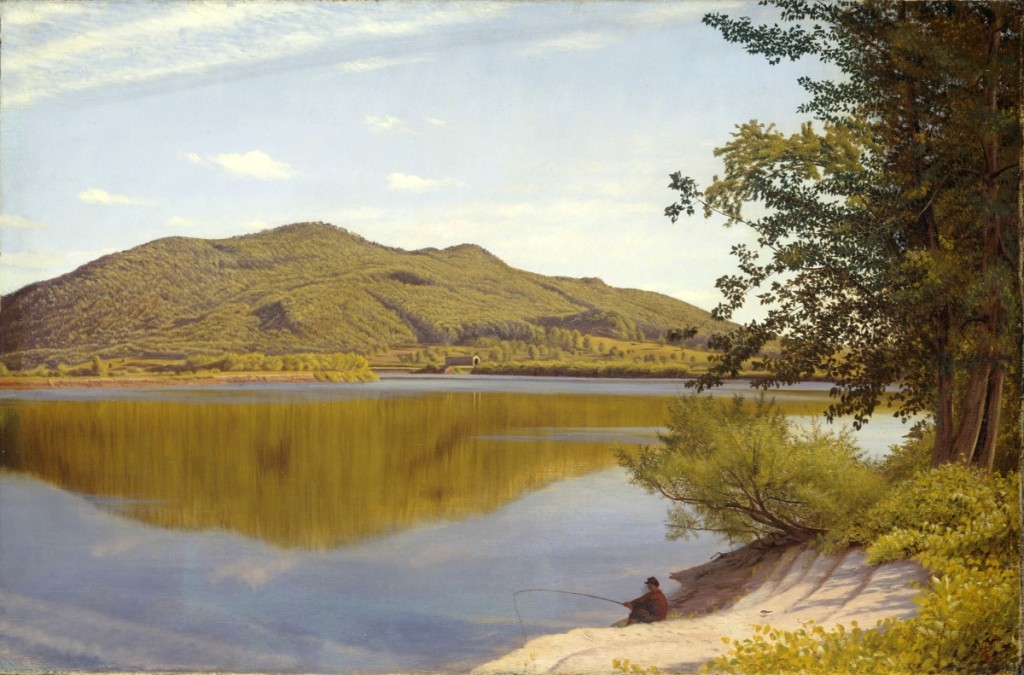

“Mount Tom” by Thomas Charles Farrer, 1865. Oil on canvas, 16 by 24¼ inches. John Wilmerding Collection.

By Jessica Skwire Routhier

WASHINGTON, DC – In this day and age, we are accustomed to the possibility that realism in painting can be radical. The photorealism of the 1970s was, in part, a reaction against the dominance of abstraction in the postwar years, and artists who continue to create illusionistic paintings on canvas today do so with the knowledge that they are going against the grain of the immersive multimedia works of art that fill blue-chip galleries and the pages of elite art journals. But for Twenty-First Century eyes, it is somewhat harder to conceive of how Nineteenth Century landscapes could be radical. Wasn’t everyone painting realistic landscapes in the 1800s? How is it possible that a group of artists who by their very name looked back, aesthetically, and not forward, provided a radical voice in the advancement of American art?

Luckily, Linda S. Ferber is ready to answer those questions. She had been ready, in a sense, for 33 years. It was in 1985 that, along with William H. Gerdts, she curated a landmark exhibition on the American Pre-Raphaelites at the Brooklyn Museum. That exhibition did much to bring to light the work of this tight-knit community of American artists who shared an allegiance to the British aesthetician John Ruskin (whose 200th birthday is being celebrated this year); it highlighted the quality of their work and the seriousness of their intellectual and artistic pursuits. It was not until after the exhibition closed, however, that new sources came to light that revealed the American Pre-Raphaelites to be truly the radicals Ferber purports them to be. The current exhibition revisits the themes of the earlier one, while using dozens of new paintings and drawings to expand significantly on the idea of radicalism as a key component of the Pre-Raphaelite movement in America. “The American Pre-Raphaelites: Radical Realists” is on view at the National Gallery through June 21.

Unpacking this requires some history and some definitions. “The key to … beginning to unravel this is that Ruskin dedicated the first volume of Modern Painters [his magnum opus, published in Britain in 1843] ‘to the landscape painters of England from their dedicated admirer,'” Ferber explains. “He urged contemporary artists in England to embrace modernity by casting off the hallowed picturesque studio traditions and replacing these and committing themselves … to painting out of doors direct from nature.” Ruskin’s dictum (paraphrased) is that artists should “reject nothing, select nothing, scorn nothing” – that they should, simply put, paint what they see, as accurately and completely as possible.

That was all very well and good, and British artists who were influenced with Ruskin did indeed produce dense and detailed landscapes along the lines of what we see in their American counterparts (William Trost Richards’ lush “Landscape” of 1863-64 serves as an example). However, the British cohort also doubled down on Ruskin’s command to throw off the artificial conventions of academic painting by looking back to a time before academic painting became the norm – to a time before the Renaissance; before, if you will, Raphael. So they named themselves the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and, while remaining committed to Ruskin’s passion for naturalism and detail, also experimented with themes related to a somewhat imagined medieval (Pre-Raphaelite) past. It is perfectly understandable to look at the red-headed fairy tale maidens of John Everett Millais or Dante Gabriel Rossetti and wonder what on earth they have to do with painting from nature. Still, Ferber says, “what you see around them is the most extraordinary landscape and botanical detail…. So I always say look at those paintings and take the figures out, and you have what the Americans were interested in.”

For the Americans, as a rule, did not call themselves Pre-Raphaelites; under the leadership of artist Thomas Charles Farrer, a British expatriate and an ardent abolitionist, they formed a group that they called the Association for the Advancement of Truth in Art (AATA) and thought of themselves primarily as “realists.” Farrer’s own landscapes, still lifes (“June,” 1867, and “Three Eggs,” 1868), and meticulous drawings (“Self-Portrait, Sketching,” 1858) serve as examples of the aesthetic that the AATA endorsed. The Pre-Raphaelite label came primarily from the press and from the knowledge that, like the English painters, they took Ruskin as their touchstone, but in actuality, as this exhibition shows, they followed a somewhat different thread of influence. The AATA was, Ferber says, “a real American art association” in that it was dedicated to reform: artistic reform, in bringing painting “back to square one” (Ferber’s words) by choosing nature over the academic studio; and socio-political reform, by using their art to comment on the urgent issues of the Civil War and its aftermath, all under the mantle of “truth.”

Unvarnished commentary was, in fact, a feature of the AATA’s reform movement. The association’s journal, The New Path (which, incidentally, gave Ferber and Gerdts the title for their 1985 show), first appeared in 1863, and right out of the gate it took aim at what it saw as ossifying trends in American painting. The journal’s take-no-prisoners criticism earned it the nickname of “The New Wrath” among some of its victims – and yet its acerbity was, in fact, a meaningful reform in an era in which arts writing often took the form of “puffery”: indiscriminate praise of everything exhibited. Ferber notes that the recent digitization of the complete run of The New Path, as well as the minutes for the AATA, gave her and co-curator Nancy Anderson the opportunity to appreciate more fully the extent to which such reforming voices were key to the founding and mission of the association.

Along with the journal, pedagogy was another way in which American Pre-Raphaelites spread their gospel of truth in art. A touchstone here was a follow-up title by Ruskin, Elements of Drawing (1857), which laid out a strategy for beginning by drawing a single leaf, stone or other elemental aspect of nature and building from there. Ruskin also advocated for the use of watercolor, which lent itself better to plein-air painting than oils, and for working on a minutely small scale, devoting extended periods of time to working out infinitesimal details. In emulation of Ruskin, John Henry Hill – represented in this exhibition, among other things by unpretentious floral still lifes and a remarkably non-majestic watercolor of Virginia’s natural bridge – produced his own instructional manual, using 25 of his own sketches as examples for students to follow. His delicately rendered “Thrush’s Nest” (1866) conveys the pleasing results of his Ruskinian training. It is worth observing that – even if Twenty-First Century artistic pedagogy is moving away from such fundamentals – the American Pre-Raphaelites’ approach to teaching came to dominate artistic instruction for well over a century.

Richards, Charles Herbert Moore (whose “Autumn Landscape” of 1865-66 demonstrates how American Pre-Raphaelites eschewed the beautifying conventions of their Hudson River School colleagues), and Farrer were among those who taught these new techniques at major national art schools. Farrer eventually landed at the Cooper Union’s School of Design for Women, demonstrating that the movement was open and accessible to women, too, in a way that the upper echelons of academic fine art often were not. One female AATA member, Sarah Tuthill, taught generations of young women at Miss Porter’s School; another, Mary Louise Booth, went on to write for the New-York Daily Tribune and helped found Harper’s Bazaar (Booth was also deeply involved in abolitionism and women’s suffrage). Ferber expresses regret that she was not able to secure any works by either Tuthill or Booth for the exhibition, but one woman, Fidelia Bridges, is richly represented. Her “Study of Ferns” (1864) is more landscape than still life, showing ferns clustering around the base of a decaying log, seemingly naturally fallen in a thick wood. There is no horizon and only the barest hint of sky: the subject is not nature’s majesty and scope, but instead the radical notion that truth lay in her humblest details.

And it was that sense of truth in representation that, in some sense, vested in American Pre-Raphaelite works the authority to convey sociopolitical truths that were radical, or at least progressive, as well. This is an aspect of American Pre-Raphaelite painting – an understudied genre to begin with – that is only starting to be explored, and the present exhibition offers tantalizing examples. The AATA’s mission, Ferber says, was “to lead the reform of American art, architecture, culture, criticism, and everything else…. They were staunchly pro-Union and anti-Slavery,” a position that is amply documented in the archival materials recently made more accessible through digitization.

“Study of Ferns” by Fidelia Bridges, 1864. Oil on board, 10 by 12 inches. New Britain Museum of American Art, Gift of Jean E. Taylor.

Take, for example, Richards’ “Neglected Corner of the Wheatfield” (1865), rendered in his typically painstaking style. Here the wild, dense foreground vegetation that is something of a hallmark for Richards and his colleagues presses up against a field of golden wheat, separated only by a decaying and overgrown fence. Ferber notes that the wheat field was a recurring motif for Richards and clearly associated with deeper meanings: he used it in a painting of abolitionist John Brown’s grave as well as in works, now unlocated, dedicated to the biblical parable of the sower from Matthew. Noteworthy here is the second, less remembered part of the parable, where the sower does battle against weeds planted by his enemy. Counseled to pull them out, he declines, “because while you are pulling the weeds, you may uproot the wheat with them. Let both grow together until the harvest” (Matthew, 13:29-30). Ferber sees in this clear connections to the battle over America’s soul that was the Civil War, as well as, more specifically, the invasion of Gettysburg by Confederate forces – for Richards was based in Pennsylvania and would have felt this keenly. “It is an allegory of sedition and good governance – of good governance and poor governance,” she adds, marveling that it is “all enacted by plants.”

The iconography is even richer in a painting by Charles Herbert Moore, titled “Hudson River, Above Catskill” and at first glance a typically humble outdoor view of a pleasant but unremarkable riverbank. But a closer look reveals telling details: a horse’s skull and rib bones, a beached rowboat without oars, and a single, round red apple in the very foreground, dead center, as if it had been carefully placed there. The painting belongs to the Amon Carter Museum, where former curator Patricia Junker developed a theory based on the painting’s date, revealed only after the painting was taken out of its frame for examination. On the perimeter of the canvas, hidden from sight, the artist had written the words “April” and “1865”: the month and year of Abraham Lincoln’s assassination. Seen in this context, Junker argued, the skull is an even stronger and more specific symbol of death; the boat without oars is the ship of state, rudderless and lacking direction; and the apple refers to the surrender at Appomattox, which took place under an apple tree. Bizarrely, and not intentionally, Ferber is quick to point out, the present exhibition actually opens on the 153rd anniversary of Lincoln’s assassination on April 14, 1865.

There is, of course, an inherent contradiction here: weren’t followers of Ruskin supposed to be guarding against such ideological interpolations? Weren’t they supposed to be depicting nature unadorned, unmediated? Well, yes – in theory. But while theory and practice were closely aligned for all Ruskinians, they were not one and the same. Just as their British counterparts found a variety of ways to heed Ruskin’s call of “truth to nature,” so did the Americans, uniting Ruskinian aesthetic ideals with deeply embedded, and deeply American, ideas about nature, land, growth, death and rebirth.

The National Gallery is on the National Mall between 3rd and 9th Streets at Constitution Avenue NW. For information, www.nga.gov or 202-737-4215.