By Laura Beach

NORTHFIELD, N.H. – The one thing all antiques dealers in the 1980s agreed upon was that show managers could be an overbearing lot. Shows were at or near their zenith, on their way to replacing shops as the primary point of retail sales. Entrée to the right events could be a dealer’s ticket to fame and fortune. Fair directors, some anyway, were consequently petty, vindictive and extortionate when it suited their purposes.

“One year, hors d’oeuvres at the opening of the Connecticut Antiques Show consisted of peanut butter, crackers and celery sticks,” Burton Fendelman, a former dealer and longtime legal counsel to the Antiques Dealers’ Association of America (ADA), recalls with perhaps a touch of exaggeration. “Dealers were loath to complain, but when the already long show hours were extended, a group of us exhibitors screwed up our courage to confront management. One by one we peeled away as we approached the office,” he says, detailing an event reminiscent of the Tinman and Cowardly Lion’s encounter with the great Oz.

The most powerful manager of all, Russell Carrell, inspired the greatest fear and loathing. Connecticut dealer Arthur Liverant remembers, “My father, Zeke, and I were doing a little show in Essex, Conn. A baby was sleeping in a carrier. When Russell came by, he looked at the baby and mused, ‘Wouldn’t it be nice if we could be that age again?’ Zeke replied, ‘If you were that age, Russell, I’d drop you in a lake.’ That’s how we felt about him.”

In short, says John Keith Russell, a founding ADA member and longtime president, “Dealers felt the management of their business was in the hands of incompetents. It wasn’t that these people couldn’t organize great shows, but they didn’t have empathy toward the dealers and were unwilling to listen.”

Looking back, Peter Eaton, another past president, remarks, “To run a show professionally, to vet shows and guarantee merchandise – those were terrific ideas. The ADA was a group of people who really cared about the business and had the courage and independence to band together for what they believed.”

Around The Table

“It’s an 8-foot table in old red paint, nice overhang, perfect for eating. There were things we sold when we needed money, but never this,” says Dan Olson. Originally from the Midwest, Olson and his wife, Karen, moved to the fieldstone Silas Gardner house, a registered historic property in Newburgh, N.Y., in 1976. They began dealing fulltime in 1982, their interest in antiques encouraged a decade earlier by Deposit, N.Y., dealer Richard “Smitty” Axtell.

“Karen and I were small potatoes, just starting out,” Olson continues. “As I remember it, about ten dealers came over to our place and we hatched the idea for an association around our table in mid to late 1983. It was a joint idea with Ronald and Penny Dionne, with whom we did business regularly at the time. As I recall, the Dionnes, Lewis Scranton, Robert Thayer, Corinne Burke, David and Susan Cunningham, Judy and Tod Overdorf, Frank Gaglio and some other local dealers were among those present at our first meetings. It focused on New York state initially, mid-country people like ourselves.”

The Call To Arms

A few months later, in June 1984, between 100 and 150 dealers gathered at the Hilton in Danbury, Conn., to formalize plans for the ADA. The nascent association was already “morphing into something else,” a trade association emphasizing ethical conduct and buyer education, says ADA treasurer Lincoln Sander. Gaglio, these days a show promoter who continues to deal, adds, “As professional dealers, we wanted to raise the level of integrity.”

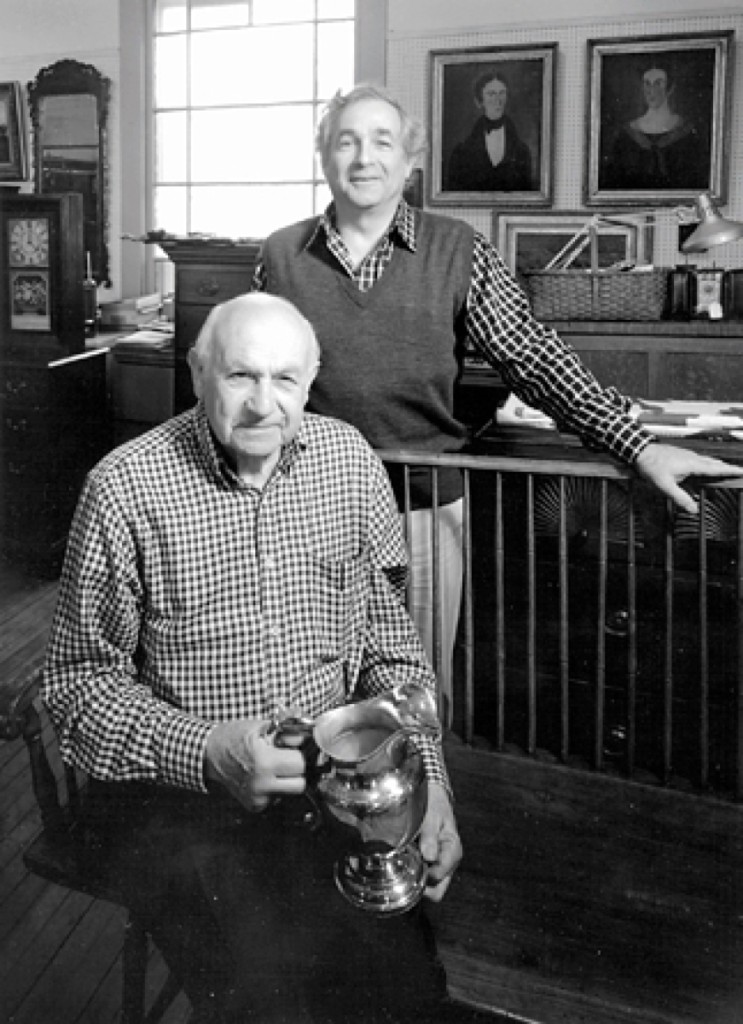

“My son and I feel it’s time for professional dealers to be self-regulated and to insist on a better level of knowledge,” Zeke Liverant, seated in his shop with his son, Arthur, said in 1984.

Elected to serve two-year terms were Dan Olson, president; Frank Gaglio, vice president; David Cunningham, secretary; and Elizabeth Kingsley, treasurer. Barry Axelband, Judy Oberdorf, Robert Thayer, Stephanie Wood, Ronald Dionne, Lincoln Sander, Gail Savage, Lewis Scranton and Elliott Snyder were named to the ADA’s board of directors.

“My son and I feel it’s time for professional dealers to be self-regulated and to insist on a better level of knowledge,” said Zeke Liverant, who underwrote the group’s first newsletter. Helaine Fendelman, an author and appraiser, issued the group’s first press release outlining the mission of the new professional organization: “to be a self-regulating organization for both the betterment of the industry and the public’s perception of the industry, and to work for the welfare of the group’s members individually and collectively.”

The Acronym War

Burt Fendelman, who gave up dealing fulltime to return to his legal practice, created the ADA’s formal structure. “It was standard, but there was a lot of input from dealers,” he recalls. The ADA received its Certificate of Incorporation in August 1984, and first used its logo, the distinctive flame finial designed by Robert Sutter, a graphic artist turned antiques dealer, in October 1984.

Fendelman applied legal muscle to win what he called “the acronym war.” The Art Dealers Association of America – the ADAA – objected to the association’s use of the same initials. The dispute was eventually settled amicably. As Fendelman wrote to Dan Olson, “We have an agreement with the Art Dealers Association of America Inc that they will not challenge the use of our name and we will use the acronym ADA only to note the activities of the association. In addition, the trademark and the trademark search are now complete.”

Let’s Put On A Show

By the time Charles Adams was elected treasurer in June 1985, the ADA’s animus toward professional show management had subsided as its focus on education and ethical standards increased. “The antiques business overall didn’t have a very good reputation with consumers at the time,” says Adams, a born-organizer who, with his wife, Barbara, is a mainstay of the lively Cape Cod Antique Dealers Association. Soon, the impulse to self-government and the desire to showcase standards coalesced in plans for an antiques show. The fair debuted on July 6-7, 1985, at what is now the Mass Mutual Center in downtown Springfield, Mass., a site roughly equidistant from Manhattan and Maine.

“Ron and I managed the show with Bob and Mary Lou Sutter,” says Penny Dionne, a retired folk-art dealer who with her husband was known for turning up choice examples of American redware – “autumn colors of New England on a dish,” as she describes it – and weathervanes. Suffield, Conn., dealer Tom Dupree “worked his heart out” to transform the drab facility into a park-like setting. More than 2,500 shoppers turned out to buy from 73 member dealers. Some – Betty Mintz of Washington, DC; Bea Cohen of Easton, Penn.; and M. Finkel and Daughter of Philadelphia, among them – traveled a great distance to participate in the fair emphasizing country and formal Americana of the highest caliber. Liverant Antiques led with a Federal cherry server attributed to Samuel Loomis III and a curly maple chest-on-chest. In the spirit of the July 4th holiday, Fred and Kathryn Giampietro featured a red, white and blue flag quilt. New Hampshire dealer Carl Staley spent two days assembling an Eighteenth Century paneled room in old blue-grey paint before flipping it to another dealer.

Education was a central feature of all ADA initiatives. Most members approached the subject with a collegial spirit. As Arthur Liverant noted, “When the dealer can improve his expertise and knowledge, everybody wins.” In its early years, the ADA published The Forum, a quarterly circular that took up topics of interest to enthusiasts. Inserted in Antiques and The Arts Weekly, the January 1989 issue of The Forum featured the article “Antique Furniture, Genuine or Fake” by Donald R. Sack, an ADA board member.

Trust But Verify

According to ADA bylaws, “Membership is composed of professional antiques dealers who are dedicated to integrity, honesty and ethical conduct in the antiques trade. To be accepted, dealers must have a minimum of four years’ experience in the trade, be recommended by a committee of peers and must sign a certification agreeing to abide by the bylaws of ADA.” Membership is by invitation and renewed annually. Misconduct can result in a member’s removal.

Grace Snyder, head of the ADA’s membership committee, with past ADA presidents Lincoln Sander and Elliott Snyder, who introduced vetting to the ADA Antiques Show in 1985. Sander is the ADA’s current treasurer.

“The ADA has always been very serious about the people it takes in for membership. It is concomitant with the show and part of the ADA’s whole ethos of ethics and transparency. Over the years, the ADA has broadened its dateline but has not relaxed its emphasis on integrity and knowledge,” says Grace Snyder, an ADA director who heads the membership committee.

An ethics committee, in which Massachusetts dealer Sam Herrup has been a vital force, is in place to handle disputes. Rumor has it that one well-known dealer, now deceased, was ejected from the show when he refused to tag his merchandise. Another is said to have resigned from the ADA after much of his material was vetted out of the ADA show.

Caveat Venditor

The ADA billed itself as the first American organization to formally vet its antiques show, a practice it introduced in Springfield in 1985. (Coinciding with the fair’s debut, Mary Lou Graham of La Jolla, Calif., wrote to Maine Antique Digest and Antiques West disputing the ADA’s claim, arguing that the Newport Harbor Art Museum in California “has been quietly and efficiently producing an elegant and quality Antiques Show since 1977,” every year of which was vetted.) The word “vet” – uncommon in American usage and meaning to appraise, verify or check for accuracy or authenticity – suggested its British precedent. Nevertheless, the ADA was four years ahead of London promoters Anna and Brian Haughton, whose International Fine Art and Antique Dealers Show, founded in 1989, was the first New York antiques fair of consequence to be formally vetted.

The “plunge into potentially dangerous waters,” as the New York-Pennsylvania Collector described it at the time, was led by Elliott Snyder, a Massachusetts dealer known for his expertise in early New England furniture and artifacts. Elliott and his wife, Grace, have over the years grown increasingly interested in even earlier European material. As Grace says, “These objects really open other worlds and horizons for you.”

-1024x766.jpg)

Amy Finkel and Elliott Snyder both exhibited at the ADA’s first antiques show in 1985 and have been active in the group from its start.

Around the time their first son was born in 1984, the Snyders traveled to England once or twice a year to buy. Elliott recalls, “Virtually all the major shows there were vetted. Antiques sold quickly, which dealers liked, because customers bought with confidence. I mentioned the possibility of vetting to Bob Sutter, who lived nearby, and the practice was adopted by the ADA. It made business sense to do it, but it was the moral thing to do, too. One person can make a mistake but when objects are viewed by committees of people, errors are much less likely. Vetting also just seemed like a great educational opportunity for dealers.”

Elliott Snyder and Robert Sutter were assisted by more than 30 vetters at the first show. Five outside experts – among them Roderic Blackburn, William Ketchum, Steven Kern and Oliver Deming – also participated. “Except for condition, we are not judging quality. We are judging the honesty of what is written on the tag,” Sutter told the press. Pieces were rejected if they had too much restoration or were too new. The cut-off date for objects was 1865, though certain categories, such as quilts, stretched to 1930.

Teams of three to seven or more vetters, all recognized experts in their specialties, began work at 10 am on Thursday. The furniture committee alone toiled for 12 hours without breaking for lunch or dinner. According to the New-York Pennsylvania Collector, 500 items were relabeled and between 75 and 100 were removed from the floor. Only two of approximately a dozen appeals to the vetting committee were successful. The response from other promoters ranged from “correct labeling is a good idea” (Sanford L. Smith) to “I vet my dealers. If they needed more vetting, I wouldn’t have them in the first place” (Russell Carrell).

“To me, vetting was one of the greatest learning experiences. We all look at things differently, and it was fascinating to see different approaches to one object. We learned that experts knew their field but might not know much else, which could result in an uneven booth. Overall, though, vetting was a win-win-win – for the buyer, the seller and the organization,” stresses Arthur Liverant.

Over time vetting became a source of conflict among members. “It could be very emotional. People don’t like criticism. It also added two or three days to the show, which substantially increased the cost to dealers,” says Elliott Snyder. Russell concludes, “Vetting was in concept a very positive event but in reality extremely polarizing. We were all going to participate, to learn, to share, but it became adversarial.”

The ADA continued to vet its shows for many years. Written guarantees in the form of receipts detailing the approximate age, origin, condition and, if any, restoration of the object sold remained mandatory after vetting was dropped around 2010. “If a buyer has a problem with one of our members, the ADA’s ethics committee will intervene in the matter if approached,” says ADA director Karen DiSaia.

On The Move

By 1990, the ADA Show had moved to the Westchester County Center in White Plains, N.Y., a hulking Art Deco-style building that years earlier hosted the Eastern States Antiques Fair, still remembered as a hotbed of Americana. The following year, New York Times reporter Eleanor Charles wrote about the 52-exhibitor vetted show, a benefit for Historic Hudson Valley. Talks by Federal furniture specialist Thomas G. Schwenke and Brock Jobe, then curator of collections at the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities in Boston, were planned. The ADA hosted the symposium, “Buying Antiques With Confidence: The Principles and Practice of Vetting” at the 1992 fair. The Fendelmans threw a party at their folk-art filled house in nearby Scarsdale, N.Y.

“It was a great venue, and right on a train line. It had so many pluses. The first year in White Plains was quite successful, the second year somewhat less so. Then the banking crunch hit. Attendance dropped and it was hard to get exhibitors to come back,” recalls Peter Eaton.

The ADA’s most enduring partnership has been with Historic Deerfield, dedicated to the heritage and preservation of Deerfield and the Connecticut River Valley in western Massachusetts. Ed Hild of Olde Hope Antiques chaired the first ADA/Historic Deerfield Antiques Show in 1998, continuing in the role after the show moved to the nearby Eaglebrook School in 1999. Karen and Ralph DiSaia, assisted by member volunteers, assumed responsibility for the fair’s management in 2003. On the grounds of Deerfield Academy over Columbus Day weekend, the ADA event blossomed into a foremost showcase for early American furniture, decorative arts and folk art, a reputation it sustained over two decades.

“The show worked really well all those years at Deerfield. There were minor problems – heat waves and flooded fields – but we figured it out. One year a group from Texas came to the show and bought, which was great,” Karen DiSaia remembers.

At the height of the market for Americana, the ADA also pursued plans for a second show. “We wanted a city show and a country show. The problem was, it takes a certain leap of faith to commit to a city show because of its cost,” says John Russell. The ADA considered venues and partnerships in Delaware and Philadelphia. In January 1989, then president Elliott Snyder wrote to members to say plans for a Philadelphia show were off, adding, “Let me assure you this had nothing to do with the so-called New England bias of the organization.”

Leadership

Most ADA presidents have served one or two terms of two years each. Frank Gaglio succeeded founding president Dan Olson and was in turn succeeded by Lewis Scranton, Elliott Snyder, Lincoln Sander, Peter Eaton, John Russell and Skip Chalfant.

“I respect the organization and its mission, and I enjoyed helping lead it in a new direction. During my tenure we revamped the website and implemented newer technology in the form of our online shows,” says Judith Livingston Loto, the group’s first woman president. When Loto, now development director at the Portsmouth Historical Society, stepped down, she was followed by Delaware dealer James Kilvington. The ADA’s current president is New York dealer Steven S. Powers.

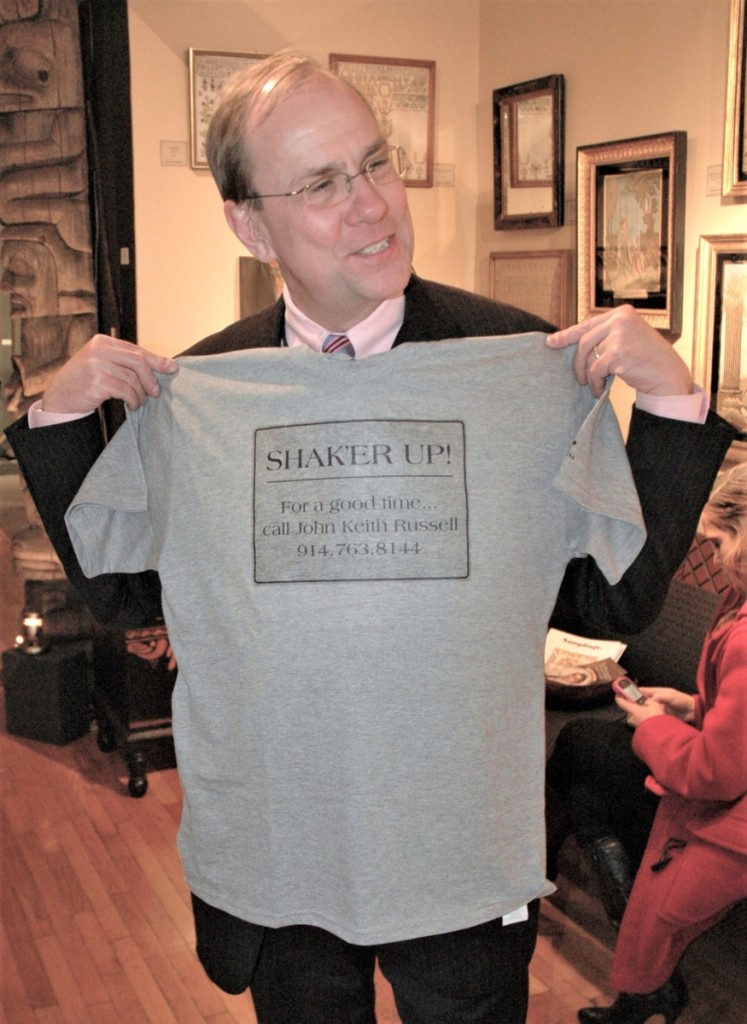

John Russell was ADA president for seven terms. He joked, “It gave me a platform for my overly opinionated self. I stopped doing it because people stopped listening to me.”

Russell was president for seven terms. He had been at the group’s helm for 13 of the association’s 25 years when he told Antiques and The Arts Weekly in 2009, “I truly enjoy the other members of the organization and the opportunity to work with people I have such admiration and esteem for.” More recently, Russell joked, “It gave me a platform for my overly opinionated self. I stopped doing it because people stopped listening to me.”

On August 28, 1987, an advertisement appeared in Antiques and The Arts Weekly seeking a part-time administrator and business manager for an unnamed professional antiques dealers’ association. The replies, addressed to Box WJ, included one from Satenig St Marie, a retired JC Penney executive and contributor to Victorian Homes magazine. St Marie started as the ADA’s first executive director in September 1987, reporting to then president Elliott Snyder. Credited with bringing organizational rigor to the association – “She was like our den mother,” Arthur Liverant once said – she worked hand-in-glove with ADA members. She formed an especially close professional relationship with Russell, president for half of her 20-year tenure. She was succeeded by Lincoln Sander and Judy Loto.

Award Of Merit

Never the ADA’s president though often an officer, Arthur Liverant has been the beating heart of the organization for much of its 35-year existence. As he recalls, “I was watching the Academy Awards one evening 22 years ago and thought the lifetime achievement award was such a wonderful ceremony and honor. The next day in the shop, I said to my father, ‘The ADA should do that. It would be nice to honor people while they are alive. Too many times we speak well of people only after they die.'” ADA president Russell agreed and the program was implemented.

The Award of Merit, whose 18-and-counting recipients range from Albert Sack in 2002 to Peter Kenny in 2018, are honored at an elegant, festive dinner at the Philadelphia Antiques and Art Show, where amid toasts and tributes, the winner receives a carved mahogany trophy resembling a flame finial on a Boston highboy. Woodworker Peter Arkell made the finial for many years. After Arkell retired, Liverant borrowed the trophy presented to R. Scudder Smith in 2006 to create the template used by Arkell’s successor.

Liverant recalls the 2015 dinner, when the ADA honored popular historian David McCullough, whose bestselling books bring the past alive for millions of Americans. “McCullough flew up from Florida for a night to accept the award. After the ADA dinner, we sat around the bar with McCullough and retired Yale University professor John Demos at the Four Seasons Hotel talking books and history. It’s a night we’ll never forget.” Though Liverant says hosting the ADA Award of Merit dinner is like “throwing a bar mitzvah every year,” the team has streamlined the process. “Greta Greenacre and Judy Loto do most of the work and have it down to a formula. They get the credit.”

ADA For A New Age

A general acknowledgement that the antiques industry needs to rejuvenate itself and that dealers must adapt to technological change was implicit in the ADA’s 2016 election of Steven S. Powers as president. Powers, a practicing artist and dealer in American folk art from Brooklyn, N.Y., has proved adept at tapping into cultural currents, from the enthusiasm of collectors, many of them young and urban, for self-taught art to the ascendance of social media, a realm where Powers excels. As president, he is a natural successor to Russell, who argues, “To be successful in this evolutionary process, you have to bring people with you and make it fun.”

Powers believes in an ADA with fewer dateline restrictions. “I embrace art from all periods,” he says, recalling a time when Modernist furniture by Wharton Esherick was considered beyond the scope of the Philadelphia Antiques and Art Show. Shy about using the word “antiques,” particularly when addressing younger audiences, he takes an encompassing view of visual culture, preferring to see work of all media judged for its formal beauty and technical excellence.

Elected in 2016, ADA president Steven S. Powers, left, here with Nancy and Ben Taylor at the Philadelphia Antiques and Art Show, is updating the organization and broadening its scope.

As part of his push for technological progress, Powers hopes to update the ADA website, which is “functioning, but a little dated.” Under his watch, the ADA has increased its presence on Instagram by posting daily. “Consistency is important on social media. We haven’t missed a day since last fall, which is good for increasing awareness of the ADA and its membership,” he says.

The ADA was born of a desire to hold professional antiques dealers to the highest standards, in doing so boosting the confidence of buyers. Is the group still relevant? “More than ever,” Powers insists. “As selling moves online, buyers are trying to gauge the unfamiliar and opaque. Knowing a dealer is respected by his peers and is part of an organization that adheres to a code of ethical conduct is invaluable. The ADA is for prospective clients, but it’s also for the dealers. No one wants to return a check because the customer didn’t know what he was getting.”

“The ADA’s mission, focus, guarantee and bylaws have not changed. The core meaning and strength of the organization is still absolutely at the forefront of its activities. But like everyone else in this new digital era, we’re all trying to find our way,” Loto agrees.

As Russell looks back over the ADA’s 35-year experiment in self-government, he says, “Probably the most valuable aspect of the ADA is that it brought a group of us together from divergent areas of interest and allowed us to get to know one another and be friends.”

For information, www.adadealers.com.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)