The Decorative Arts Trust made more than 150 awards to young scholars over the past two years. Several recipients spoke at a trust-sponsored symposium in Newport in June. At left, presenters Emilio Ruiz, Jenn Robinson and Taylor Bye. At right, presenters Lea Stephenson, Mariah Gruner and Dan Sousa. Center, from left, Trudy Coxe, chief executive officer of the Preservation Society of Newport County; Matthew A. Thurlow, executive director of the Decorative Arts Trust; and Leslie Jones, the Preservation Society’s director of museum affairs. —Photo David Hansen, courtesy Preservation Society of Newport County.

By Laura Beach

MEDIA, PENN. – Set aside what you think you know about the Decorative Arts Trust and consider this. In the past three years, the organization, which arose during the Bicentennial years and is known for well-planned forums and symposia, has awarded 156 educational scholarships, research grants, curatorial internships and speaking engagements to promising young scholars about whom you are likely to hear more. To do so, it has allied itself with dozens of museums, historical societies and academic research programs, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Winterthur, Colonial Williamsburg and the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts (MESDA) among them.

Over the past decade, while some of their peers lamented what they perceive to be dwindling public interest in antiques and diminished opportunities for graduates of decorative arts and material culture studies programs, trust members took decisive steps to counter those trends. Efforts have accelerated since 2014, when Matthew A. Thurlow took over as executive director of the not-for-profit organization founded by Dewey Lee Curtis (1924-1986), the Rolodex-wielding former admissions officer, curator and sometimes antiques dealer.

Thurlow likes to think of the trust as a kind of community foundation, a description that seems especially apt in the close-knit world of curators, collectors and members of the trade. But while community foundations typically fund projects within specific geographic areas, the trust supports a community whose defining geography is the historical past.

This fall, the Decorative Arts Trust is embarking on the public phase of a $2 million capital campaign. Called “Providing a Future for Students of the Past,” the drive seeks to create a permanent endowment from which to underwrite expanded educational and employment opportunities for young professionals through the trust’s existing Emerging Scholars Program.

Education has been central to the trust’s activities since its founding in 1977. Having underwritten student attendance at its symposia from its beginning, the trust in 1981 began supplying the financial wherewithal for young scholars to attend MESDA’s Summer Institute, the Winterthur Institute and the Attingham Summer School, where students benefitted from interaction with leading curators and gained practical experience handling objects. In 2003, largely through the intercessions of Winterthur professor Brock Jobe, Thurlow received the trust’s first summer research grant for master’s and PhD candidates. In the depths of the Great Recession, when jobs for newcomers were scarce, Jobe lobbied for the trust’s curatorial internship program.

Today, the trust typically awards ten research grants a year, along with matching grants for two two-year curatorial internships. The trust also supports lectures by young scholars at its own symposia as well as at outside conferences. Since 2016, the trust’s Dean F. Failey Grant, named for one of the group’s most energetic supporters, has funded exhibitions, publications and a digital workshop at Boscobel House and Gardens, Winterthur Museum, Yale University Art Gallery and Long Island Museum of American Art.

“In the near future, the trust hopes to fully fund these collaborative internship positions. We want to tap into organizations up and down the spectrum that have something to offer an aspiring curator but perhaps do not have the financial wherewithal to match trust funds on a one-to-one basis. We see these partnerships as beneficial for all involved,” Thurlow explains.

Over time, the trust’s programming and grant making activities have broadened beyond their historical roots in Americana. “Our summer research grants, for instance, could not possibly be limited to the traditional Americana investigations of years past. Through the Emerging Scholars Program, we now support research and experiences that range across time and place. Many more students today are focused on Twentieth and Twenty-First Century topics. We continue to support those focusing on earlier periods, who are typically asking different questions than scholars had previously done,” Thurlow acknowledges.

The campaign is the trust’s largest fundraising effort to date. “We are now 80 percent of the way towards our $2 million goal, which gives us an important foundation to build upon down the home stretch. Our next step is to turn toward the trust’s full membership and the broader decorative arts community to look for additional help. We need to raise another $400,000. It’s important to note that we don’t derive any operational support from the Emerging Scholars Program even though there is a significant responsibility of administering it and marketing it,” says Thurlow, who hopes to complete the drive in 2020.

The Decorative Arts Trust is also looking toward 2026, when the United States will celebrate its 250th anniversary, and beyond. “We have created a niche and want to build on that,” says Thurlow, whose commitment to education is firm. “From my perspective, we will be hard-pressed to increase the diversity of our field without gaining the interest of younger people. It’s my personal pie-in-the-sky wish, but we should ideally be thinking about how to introduce material culture to high schools and middle schools.”

Children are the future, as the saying goes. Intrinsic to the Decorative Arts Trust’s Emerging Scholars Program is the conviction that tomorrow’s decorative arts establishment will reflect the interests and activities of those in the formative phases of their careers today. Summing up the trust’s position, Thurlow says, “We want to help insure that material culture and the arts remain relevant to contemporary society through the young people coming forward in the field.”

For more information on “Providing a Future for Students of the Past” or to make a gift in support of the campaign, visit www.decorativeartstrust.org/campaign, contact thetrust@decorativeartstrust.org or call 610-627-4970.

Laura Beach is editor-at-large of Antiques and The Arts Weekly and a governor of the board of the Decorative Arts Trust.

Young Scholars Share Their Views

Since 1977, hundreds of arts professionals have advanced their training and careers with awards from the Decorative Arts Trust. Antiques and The Arts Weekly asked five recent recipients to share their aspirations and thoughts on the future of the field in a rapidly changing social and professional environment.

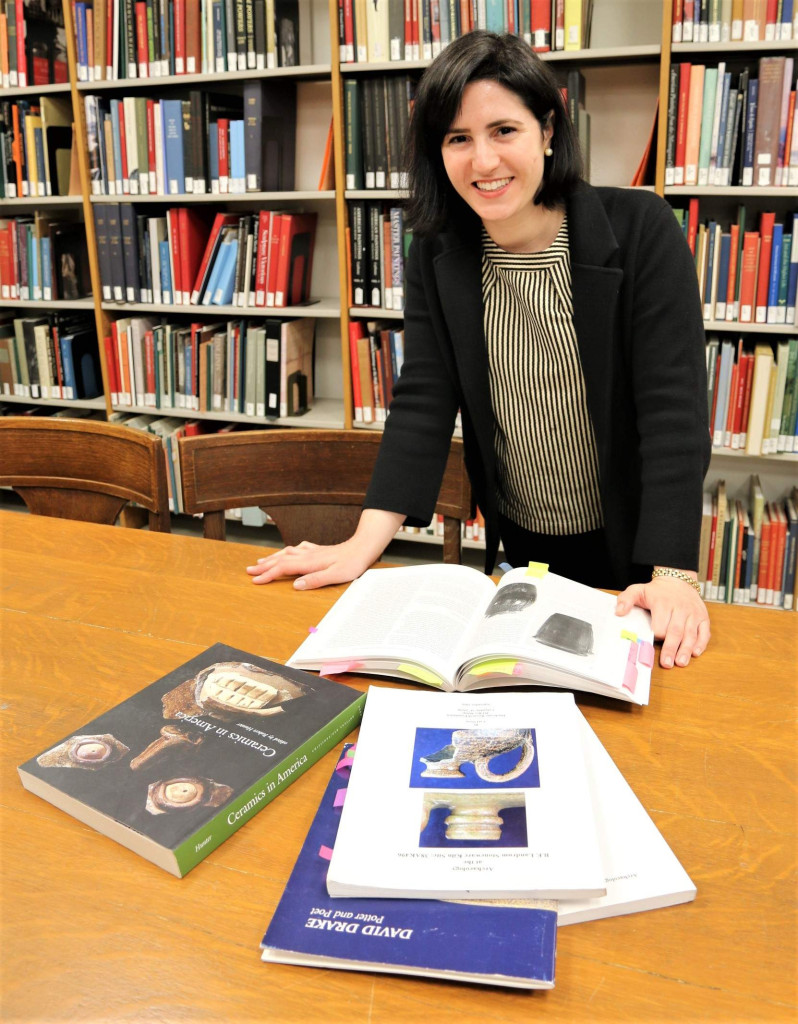

Supported by the trust, Katherine C. Hughes has just completed the first of two years as the Peggy N. Gerry Research Scholar in the American Wing at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Her chief project there is working with assistant research curator Adrienne Spinozzi on an upcoming exhibition on the Nineteenth Century stoneware of the Old Edgefield District in South Carolina. Hughes’ deep resume also includes fellowships, internships and staff positions at, among others, the New-York Historical Society, Historic Charleston, Christie’s, the Winter Show and Ralph Harvard Inc.

Q: What all does your work at the Met entail?

I’ve been fortunate to be involved in a myriad of ways — accessions and deaccessions, installations and label writing, leading tours and gallery talks. It’s been a particular pleasure to work with the Southern ceramic objects in the collection. The American Wing and the Decorative Arts Trust have also been incredibly supportive of research and speaking opportunities while I am in this role, and I’ve had wonderful opportunities to share my research and work.

Grant recipient Katherine C. Hughes is working with American Wing curator Adrienne Spinozzi on a study of Edgefield, S.C., stoneware.

Q: Where do you see yourself in the future?

I’ve been very fortunate to have a wide array of experiences in both the nonprofit and private sectors over the past six years. I do believe these have bolstered my experience and knowledge of the art world in ways that only one or the other could not have done. I see the work I’ve done thus far as building a lifetime career.

Q: Are traditional American decorative arts studies passé?

We need fresh takes on our nation’s beginnings. Buildings, and the archaeology and landscapes they sit on, still have more stories to tell. The history and stories they hold will be lost forever without action.

Q: How do we engage new audiences?

I’ve found the American decorative arts world to be warm and welcoming, but it still needs to grow more inclusive in its storytelling. More stories of women. More stories from people of color. The history of the everyday, the day-to-day. That’s what I’m drawn to about material culture and objects.

A dynamic speaker who has presented at two trust symposia, Mariah Gruner, a doctoral candidate in American Studies at Boston University, uses needlework produced in the 1830s and 1840s for the abolitionist movement as a mode to investigate how the medium enabled radical reimaginings of women’s political place. Trust funding recently allowed her to explore abolitionist needlework in the collections of Colonial Williamsburg, Historic New England and the Peabody Essex Museum.

Q: On what are you currently working?

I’m writing a dissertation chapter on the uses of needlework in the abolitionist movement in the United States. I’m also researching suffragists’ disparate uses of embroidery in England and in the United States. This will eventually be another chapter in my dissertation on the political uses of American women’s decorative needlework from 1820 to 1920. I’m also teaching a writing class for first-year students at Boston University called “Silverware to Skyscrapers: Objects, Power, and Hidden Histories.” We’re exploring how to write engagingly about objects and how to tell stories about culture and power using objects as our main sources.

Q: Where do you see yourself in the future?

What I know for sure is that I see myself continuing to use objects to help people see new stories about our past and present and connect with those stories in real, felt ways. I hope to be able to fuse teaching with more directly object-oriented work, perhaps in a museum or other organization with a collection that is used to communicate a narrative or narratives to the public. At core, I know that I am particularly committed to unpacking the ways in which gender is constructed, performed and policed in material ways and that that will continue to animate my scholarship and teaching, whatever form they take.

Q: What exhibition would you most like to organize?

I’d love to organize an exhibit that puts the current vogue for feminist, political, popular embroidery in conversation with older forms of needlework. I’m fascinated by the needlework that is all over Instagram at the moment, particularly that which is done by people who don’t identify as artists or even artisans.

Q: What advice do you have for scholars younger than yourself?

Study the objects that call to you, the objects that endlessly fascinate you and the objects that you sometimes feel you can’t quite figure out. Those questions will keep animating you and will make for a long, fruitful relationship. I would also advise against coming to a set of objects with an expectation of the argument they’ll help you make or the story they’ll help you tell. Objects can be unruly, wily things and we do our best work when we listen really honestly to the (sometimes surprising!) stories that they have to tell.

Q: How do we engage younger audiences?

Younger audiences are already interested in making (there are so many “maker spaces” now and young, hip craft circles!) and in the meanings of the material world around us. We can work to show how historical objects are connected to contemporary issues — how they literally shape the world that we move in and think in. It’s also important to recognize how empowering it can be to learn to “read” objects. Our world is made up of things, and it can be very enabling to understand where those things came from and what they mean.

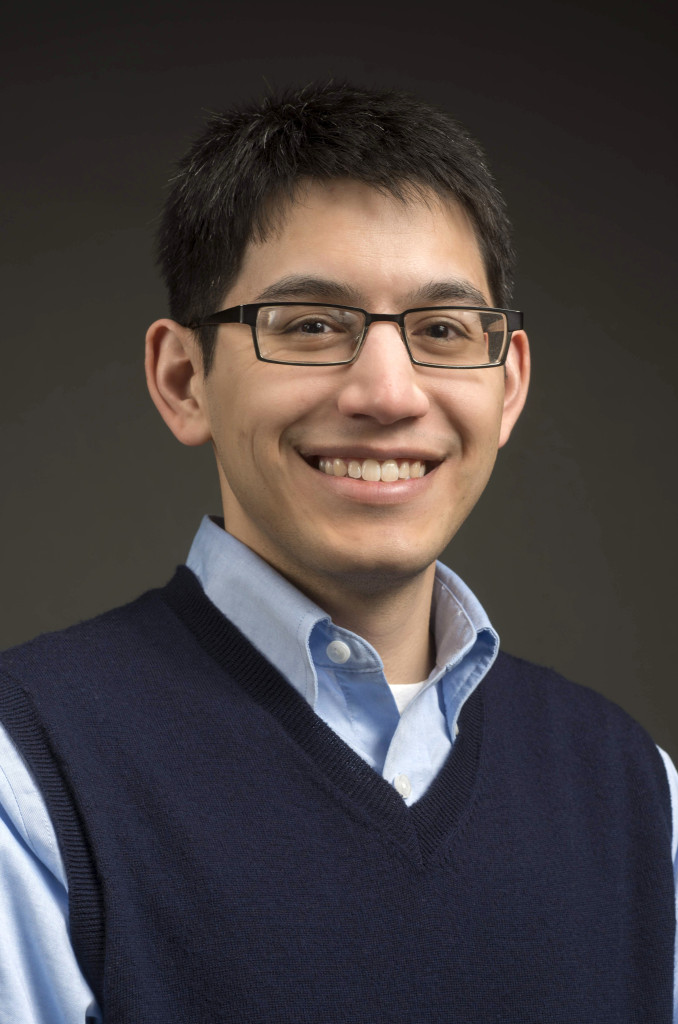

Dan Sousa

A two-year trust-funded curatorial internship led to a permanent position as assistant curator at Historic Deerfield for Dan Sousa, who previously worked as an auction assistant at Skinner Inc and interned with the Boston Furniture Archive project. A former staff researcher at the New England Historic Genealogical Society, Sousa combines a love of American history and material culture with a solid grounding in genealogical research.

Q: Your current project?

I’m working on an article with Historic Deerfield colleague Christine Ritok on the life and furniture of Greenfield, Mass., cabinetmaker Daniel Clay (1770-1848). A separate, but larger, ongoing project entails the writing of a catalog, with curator Amanda Lange, on the museum’s extensive English ceramics collection. The catalog will likely include more than 100 object entries in addition to several introductory essays, one of which will address the presence and sale of English ceramics in New England’s Connecticut River Valley.

Q: What show you would like to organize?

As we prepare to celebrate America’s 250th anniversary in 2026, I’d be very interested in organizing an exhibit and accompanying catalog that both showcases Historic Deerfield’s incredible collection of Revolutionary War artifacts and tells the story of life in Deerfield during the war.

Q: How do we reach new audiences?

Keep museum content up-to-date and relevant. Young people may think the story of early America is written and done. As museum professionals, we know this is far from the truth. The narrative of history is always changing as new sources are found and events of the past are analyzed through new interpretative lenses. It’s important that museums share their new research with the larger community through exhibitions, workshops and seminars and that young people know that museums are sites of research and inquiry.

Q: How did the trust help you?

As an intern at Historic Deerfield, I benefited immensely from working closely with Amanda Lange, an excellent mentor. The trust also generously funded my research trips and attendance at conferences and symposia, activities that introduced me to a wide network of museum professionals.

A two-year trust-funded curatorial internship led to a permanent position as assistant curator at Historic Deerfield for Dan Sousa.

A second-year graduate student in a program offered jointly by Parsons School of Design and Cooper Hewitt, Rachel Pool is researching the influence of Scandinavian design in midcentury, postwar suburban houses in the United States. Her current focus is the 1940s to 1960s program of experimental residential architecture known as the Case Study Houses. A summer research grant from the trust allowed her to survey Case Study House No. 8, designed by Charles and Ray Eames, who furnished it with their eclectic collections. “The visit inside the home with Charles’ granddaughter was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity,” Pool says.

Q: Where do you see yourself in 20 years?

I aspire to be a curator at a leading museum of design or a professor in the history of design.

Q: What show would you like to organize or book would you like to write?

I’d love to organize an exhibition about the proliferation of Native American decorative arts seen in the collections and homes of well-known architects, designers, collectors, socialites and cultural influencers in the first half of the Twentieth Century. I’d like to write a book on the foreign influences seen in Twentieth Century American architecture and design, arguing that the United States does not have a national design style and that our design history is parallel to our social history.

Q: Advice for young scholars?

Apply for every opportunity — scholarships, grants, awards, conferences — you qualify for. It’s a fantastic way to network within the field. Also, pursue a master’s degree, visit museums and read about your areas of interest to enrich your knowledge base and build a foundation within your desired specialty.

Q: How do we engage young audiences?

Complimentary events for museum/gallery openings and lectures are key. Social media presence is also a way to engage younger audiences within the field. Teenagers and young adults are more likely to discover a new magazine, exhibition or design-related event if it is from their Instagram feed. Instagram has revolutionized the way to search things with its hashtag feature.

A tea album in Historic Deerfield’s collection prompted Tammy Hong, recipient of a continuing education grant from the trust, to study Chinese tea culture and painting traditions, an inquiry that intensified her desire to “highlight narratives often underemphasized in American history.” Currently a fellow at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, Hong, a Syracuse University graduate with an interest in materials, hopes to bring scientific and art historical disciplines to bear in her career as an art historian or conservator.

Q: Your current project?

I’m researching Nineteenth Century British watercolor boxes that contain Chinese ink sticks. Through examining how Chinese ink was interpreted in a Western context, I hope to further investigate the exchange between China and the West — a topic that was explored in my previous research on Chinese tea culture and painting traditions.

Q: What book or show would you like to write or present?

The working title of the book I want to write is Traces of China: Chinese Painting Traditions, Techniques and Materials in a Nineteenth Century Western Context. I’d like to organize a show titled “Ivan Meštrovic: The Life and Work of an American Artist.” Meštrovic was a renowned Croatian-American artist of the Twentieth Century whose work is little-known in the United States. He was the topic of my undergraduate thesis.

Q: Advice for younger scholars?

Always approach art historical research with the awareness that history is a collective memory of interwoven narratives. Be aware that there are many ways to interpret this collective memory. The narratives you choose to illuminate may very well reveal a different truth about the same story.

Q: How did the trust help you?

It provided me with the platform to bring more attention to the dual histories of Chinese export art, a topic that is not only one of my research interests but is also extremely important to my identity as a Chinese-American.

Currently a fellow at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, Tammy Hong, center, is interested in materials.