Francis Howe House Mural (first-floor hall), by Rufus Porter and Stephen Twombly Porter (American, 1816-1850), West Dedham (now Westwood), Mass., signed and dated 1838. Distemper paint on plaster. Private collection. —David Bohl photo

By Rick Russack

BRUNSWICK, MAINE – Detailing the life and works of Rufus Porter (1792-1884), the Bowdoin College Museum of Art presents “Rufus Porter’s Curious World: Art and Invention in America, 1815-1860,” mounted in tandem with a 144-page catalog and on exhibit through May 31.

The exhibition has nearly 100 illustrations of works that can be fairly attributed to Porter and some of his contemporaries, including his oldest son, Stephen Twombly Porter, Moses Eaton, Abel Bowen and others. It also illustrates a number of his inventions.

Porter was ahead of his time in many ways; he was one of the most creative, inventive and colorful figures of the Nineteenth Century. Generally unknown to too many people, collectors of Americana will probably be familiar with his name as a painter of profile portraits, some will know him as the painter of murals on the walls of numerous northern New England homes, and some may remember him as a prolific inventor and publisher. He researched and designed a flying airship 50 years before the Wright Brothers and patented at least two dozen inventions. Although he founded Scientific American in 1845, the oldest continuously published magazine in the United States, he sold it after just a few months, but his name remained on the masthead for the next few years.

His numerous inventions were useful in the home, on the farm and in the factory but he never substantially profited from any – although his design for a revolving rifle cylinder, which sold for $100 to Samuel Colt, helped to revolutionize the firearms industry. Porter married twice and fathered 15 children. He moved frequently from town to town and traveled as far as Virginia. This exhibition, and the accompanying catalog, describes his life story and his many accomplishments.

The show features more than 40 of Porter’s paintings, publications and inventions, including the only known tall case clock he made. The material is drawn from more than 25 institutional and private collections and many of the objects are being shown for the first time. The exhibition and catalog provide the first scholarly inquiry into Porter in nearly 40 years and add significantly to the understanding of Porter’s life as an artist, author, publisher and inventor.

The catalog is divided into three chapters. Chapter one, written by Laura Fecych Sprague, “Rufus Porter: A Life in Motion” (comprehensive, with 172 footnotes); chapter two by Deborah M. Child, “Rufus Porter’s Miniature Portraits: Practice and Patrons” (59 footnotes); and chapter three, written by Justin Wolff, “Itinerancy, Aerial Navigation, and the Many Networks of Rufus Porter” (132 footnotes). The catalog also includes an appendix and extensive bibliography.

The catalog is divided into three chapters. Chapter one, written by Laura Fecych Sprague, “Rufus Porter: A Life in Motion” (comprehensive, with 172 footnotes); chapter two by Deborah M. Child, “Rufus Porter’s Miniature Portraits: Practice and Patrons” (59 footnotes); and chapter three, written by Justin Wolff, “Itinerancy, Aerial Navigation, and the Many Networks of Rufus Porter” (132 footnotes). The catalog also includes an appendix and extensive bibliography.

The exhibit focuses on Porter’s life and work from 1815 to 1860, when he was at the height of his career. During this period, he lived largely in Massachusetts with residencies in New York City and Washington, DC, from 1840 to 1854.

Sprague’s essay explores the surroundings that Porter grew up in and the factors that influenced his later activities. Key among these influences was the time he spent as a student at the progressive Fryeburg Academy where he was enrolled at the age of 11. That academy’s first president was Daniel Webster and he was succeeded by Reverend Amos Jones Cook (1777-1836), a Dartmouth College graduate. With these leaders, it was, unsurprisingly, ahead of its time in many ways and one of the first to admit girls. Cook developed an extensive library and a Cabinet of Curiosities, to which Porter was exposed. Porter’s family moved to Portland when he was about 18, exposing him to a larger world and then later to Boston – an even larger world.

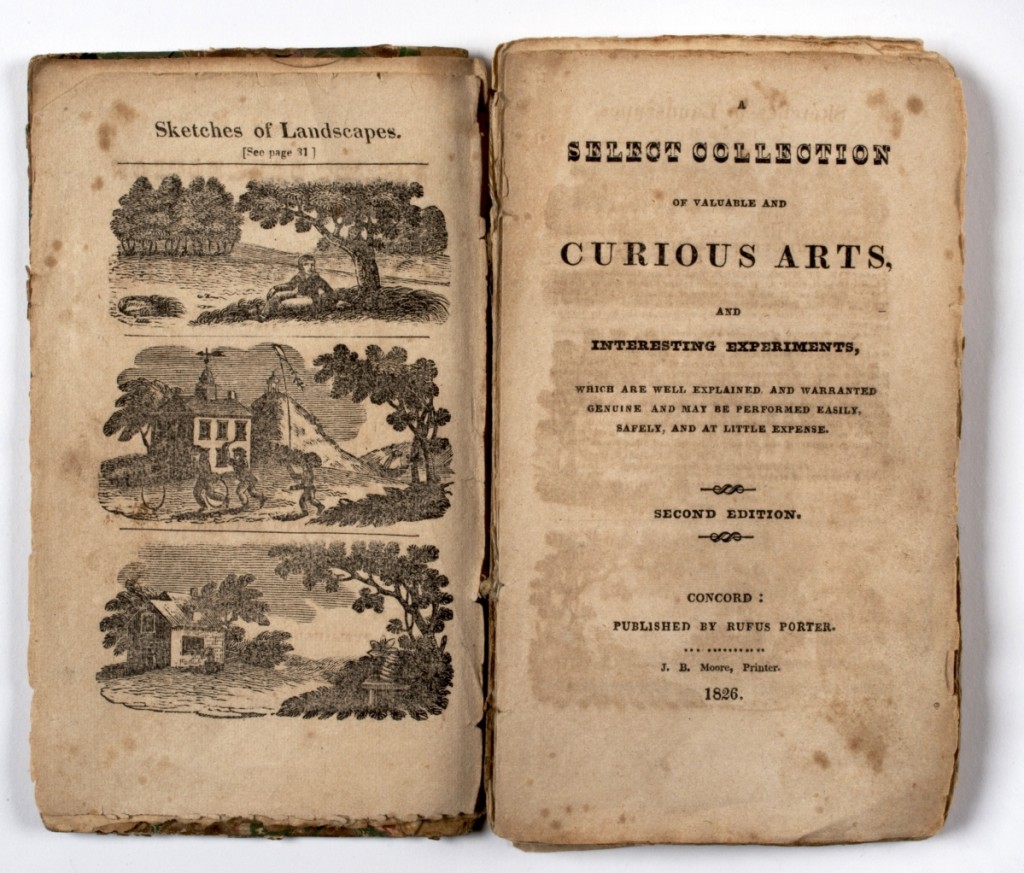

Porter willingly shared what he learned, including the techniques he developed to quickly and efficiently produce his murals and portraits, for which he used stencils and the camera obscura. Instead of guarding those techniques and many others as trade secrets, he published them: first in Select Collections of Valuable and Curious Arts, and Interesting Experiments (1825), reprinted in 2009, and later as a series of columns in Scientific American. These publications include numerous how-to instructions for painting miniatures and other ornamental paintings – window shades, floor cloths and paintings on walls. Later publications continued to share his work. In an 1846 article in Scientific American, he gave directions for painting the distinctive type of portraits he is best known for. His obituary, published in Scientific American, September 6, 1884, made note of his varied interests and itinerant lifestyle: “In 1813 he painted sleighs at Denmark, Maine, beat the drum for the soldiers in a Massachusetts (Maine was still a part of Massachusetts at this time) Militia company, taught others to do the same, and wrote a book on the art of drumming. This probably was his first book; many others would follow. After the militia he taught school at Baldwin (Maine), married in Portland (Maine), taught at Waterford (Maine), made wind-powered grist mills at Portland, painted in Boston, as well as in New York state and New Jersey and he traveled to Baltimore and Alexandria, Va.”

Sally Wetherbee Adams and Joseph S. Adams, attributed to Rufus Porter, circa 1833. Watercolor and graphite. Private collection.

The obituary also discusses his life after leaving the Scientific American. “He was now very prolific with inventions. The moment a new thing occurred to him, he made a drawing and description and sold the whole or a share for a small sum; and then worked out some other idea, to be sold in the same manner. The mere catalog of his inventions would be tedious. Among them were a flying ship, which he promised would fly miners to the California gold field in three days, an air blower, punching press, trip hammer, pocket lamp, pocket chair, fog whistle, wire cutter, engine lathe, clothes dryer, grain weigher, camera obscura, spring pistol, engine cut off, balanced valve, rotary plow, reaction wind wheel, portable house, paint mill, water lifter, thermo engine, odometer, rotary engine and scores of other inventions.”

His paintings and inventions, to some degree, reflect the attitude of his predecessor Robert Fulton and his contemporary Samuel F.B. Morse. These men were also artists, noted for their portraits and other paintings, before turning their attention to the inventions such as the steamboat and electric telegraph, respectively.

Porter began to come to the notice of antiquarians in 1926 when Edward B. Allen included Porter’s ornamental murals in Early American Wall Paintings, 1710-1850, and Louise Karr highlighted Porter’s signed murals in West Dedham (now Westwood), Mass. A generation later, Jean Lipman published Rufus Porter, Yankee Wall Painter (1950) and she expanded her scope with Rufus Porter, Yankee Pioneer in 1968. Those publications have served as principal references on Porter’s life and work ever since. Laura Sprague and Justin Wolff, in their introduction to the catalog for this exhibition, posit that Lipman was in error with some of her attributions.

Few of Porter’s wall paintings are signed and only four of his miniatures are signed. Both Sprague and Child attribute this to the fact that Porter looked at these endeavors as money-making pursuits. He did not aspire to produce fine art. One of his advertisements stated that it would take only ten minutes for him to produce a likeness. As an entrepreneur, Porter sought to attract as many sitters as possible regardless of their social standing, and his clients ranged from boot makers, farmers and tavern keepers to publishers and state representatives. As active participants in the industrialization that was transforming New England, they likely had much in common with Porter. Most of his miniatures were produced in a ten-year period from 1820 to 1830 and most were produced within 50 miles of Billerica, Mass., his hometown. Only two were done of his own family members.

Although portrait miniatures first became popular in the United States in the 1760s, they were not inexpensive, most being done on copper or ivory. As economic prosperity increased so did the demand for miniatures. Porter, and others of his time period, worked on paper and were able to charge far less, although obtaining the high-quality paper needed for rendering fine details was difficult. Porter used mechanical devices such as the camera obscura to reduce the time needed and therefore the price he would charge.

Woodblock prints of “Sketches of Landscapes,” attributed to Abel Bowen, frontispiece in Rufus Porter’s A Select Collection of Valuable and Curious Arts, and Interesting Experiments, Which Are Well Explained and Warranted Genuine and May Be Performed Easily, Safely, and at Little Expense, 2nd ed., (Concord, N.H.: J.B. Moore, 1826). Private collection.

—David Bohl photo

According to Child, Porter’s miniatures have “distinguishing features that set them apart. His sitters, when shown in profile, have a forward gaze, and their pupils have a distinctive oval shape. A deep reddish-brown line defines the separation of their lips, and the hollows of their ears are often a unique C-shape. A reliable method for identifying Porter’s style is to compare his instructions for miniature painting with his attributed portraits.” Those guidelines appeared in “Miniature Painting,” published in Scientific American, January 22, 1846. Although Child has identified 120 miniatures that can be attributed to Porter, only four are signed. No account books have yet been discovered that might add to the knowledge of his works. Porter’s final miniatures of identified sitters coincided with the advent of daguerreotypes in 1839. For all of his artistic and technological know-how, Porter exhibited no interest in pursuing this new medium.

His wall paintings also present recognizable features. Unlike other decorative painters, such as Moses Eaton Jr (1796-1886), whose cutout patterns filled walls with repetitive geometric designs, Porter used stencils selectively to facilitate the inclusion of “houses, arbors, villages, & c.” They saved him time, but his process was more sophisticated than Eaton’s because the exact size and placement of each element had to fit within the perspective of his landscape scenes.

Of the dozens of New England wall paintings attributed to Porter by Lipman and others, only three are recorded that bear his signature. Created in Massachusetts, not far from his home in Billerica, they decorated the Emerson house in South Reading (now Wakefield), the Joseph Gardner house in Woburn, and the Francis Howe house in West Dedham (today Westwood). Porter’s surviving Emerson and Howe murals provide the foundation for understanding his practice, his stylistic preferences and the true nature and extent of his work in this genre. Other ornamental painters were inspired and encouraged by Porter’s enthusiastic promotion, so it is not surprising that many New England houses bear wall paintings in the “Rufus Porter Style,” that is, murals featuring panoramic landscapes, sometimes paired with stenciled borders. Porter, however, was the master and his perspectives, his designs, his technique and the quality of his execution is superior to others. Again, he shared his techniques and elaborated on many technical and stylistic details for creating panoramas in Curious Arts and, especially, his “Art of Painting” series in Scientific American in 1845 and 1846. By combining a study of motifs with a careful analysis of his signed work, his iconography, use of perspective, painting style, technique and materials, a coherent group of murals emerges that can reasonably be ascribed to him.

Porter’s inventiveness and itinerancy is discussed in depth in chapter three, the essay by Justin Wolff. He quotes an English obituary writer, Porter was “representative of American genius” and renowned for a “long career of usefulness as an inventor of turbine waterwheels, windmills, flying ships, rotary engines, and sundry contrivances for abolishing as far as possible agricultural labor.” Wolff says, “however, many of Porter’s patented devices – his self-adjusting cheese press for instance, or combined chair and cane failed to catch on. Even more ignominiously, he traded the production rights to his revolving rifle to Colt for a mere $100; sold Scientific American, now the longest continuously published magazine in the United States, for several hundred dollars; and failed to launch anything except a small model of his much-hyped flying machine, which he promised would fly from New York to California in three days. Porter lacked the business acumen and fiscal discipline required to succeed in the marketplace. He was, according to his own son, ‘prolific’ and ‘inventive’ but also ‘improvident.'”

Although he worked on numerous inventions, his passion, for a 20-year period, was development and promotion of his idea for aerial navigation, his “aeroport” or “travelling balloon.” By flying his scale models in New York and Washington, Porter successfully demonstrated his vision for mechanized flight.

Bowdoin’s exhibition is long overdue and visitors are sure to come away with an expanded understanding of a fascinating individual.

Bowdoin College Museum of Art is at 9400 College Station. For information, www.bowdoin.edu/art-museum or 207-725-3000.