In her 2019 book, Inside the Head of a Collector, Shirley Mueller, MD, recounts a cultural enrichment trip she made in 1996 with a group organized by the Peabody Essex Museum to Haarlem, the Netherlands. Seeking a break from the sensory overload of the museums there, she struck out on her own on the city’s streets in search of her collecting passion – Chinese export porcelain. Finding no prized pieces in the local antiques shops and running short of time to rejoin her group, she made one more visit, encountering no stellar items but striking up a conversation with the shop’s owner, a ruddy-faced Dutchman, who invited her to accompany him to his upper-level living quarters to see some special pieces. Does she take him up on his offer on the chance that she may encounter her heart’s desire? Or does she politely demure, not knowing if the man has other intentions and having no way to let anyone from her group know where she is? These conflicting thoughts set up a discussion on risk-taking in the mind of a collector, just one of the compelling topics Mueller addresses in her book on the intersection of science and art. We asked the adjunct associate professor of neurology at Indiana University about some of these scientific moments.

Okay, a new term for us to understand – neuroeconomics. What does it mean?

Neuroeconomics is the study of the biological foundation of economic decision-making of which collecting is a subset. One important tool used in this discipline is the Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fRMI), which was not available until the early 1990s. Therefore, the contents of my book are based on this and other new information. Using fMRI, the emotional part of the brain known as the limbic system has been identified as important in the decision-making process. This is contrary to earlier opinion that the rational brain, also known as the neocortex, played the dominate role.

You cite your exhibit “Elegance from the East: New Insights into Old Porcelain,” a 2017 exhibition at the Indianapolis Museum of Art, as one of the first museum exhibits to use a neuropsychological approach. How did you achieve this?

I connected the past to the present through neuropsychological insights that prompted visitors to replicate their own desires and interests similar to those of consumers several hundred years ago. This approach is possible because our brain hasn’t changed substantially in the 400 or so years since the porcelain was made, purchased and appreciated. Then, as now, humans search for pleasure, intellectual stimulation, profit and social interactions while also experiencing miscommunications and pain.

Besides collectors, what other audiences can benefit from your book’s ideas?

Dealers and museum professionals as well as the anyone who wishes to learn about her or himself as a consumer of products.

You were on a lecture tour this past fall to promote the book. What was a highlight?

My presentation at Asia House in London. Many more people attended than originally expected. This large audience seemed to bring out my speaking ability to the maximum. Not only did I enjoy giving the lecture, but my audience seemed to take pleasure in hearing it.

When does collecting become an unhealthy obsession? How do you explain hoarding?

When objects replace humans as the focus of life. This means that instead of art being placed in an inanimate category meant to beautify and enrich as an accessory to living, it takes on a human form to an individual who is often simultaneously lacking meaningful human interaction for whatever reason. This is different than hoarding, which normally involves indiscriminately collecting minor objects. Fortunately, only 1-3 percent of collectors are hoarders. In my mind, the two really have little relationship to each other. Collectors enjoy their collections. Hoarders do not.

Why is an affordable reproduction of a painting, sculpture or piece of furniture not as satisfying as owning the original?

This relates to essentialism, which means we respond to beliefs about object as well as the object itself. There are several pieces of scientific evidence that support this line of thinking covered in my book.

How do you explain Cattelan’s $120,000 banana duct-taped to a wall?

Apparently Cattelan likes fully ripe bananas, and that makes me happy for him as he was able to display what appealed to him. As for his audience and the buyer, I think they were responding to novelty – and the hype of the event. There is a brain area that is stimulated when we are exposed to an oddball situation like this one. It is the substantia nigra/ventral tegmental region, which is rich with dopaminergic neurons known to be part of the reward system which can strongly influence behavior.

You mention the benefits of making social connections in collecting. An example from your own experience?

There are too many to even try to describe; my answer would take pages. Thereby, I will mention one from my book, and, in fact, will quote from it: “Loneliness gripped me in London. I was there in the early 1990s for the Ceramics Fair by myself. Having just begun to collect Chinese export porcelain, I didn’t yet know anyone in the field…That is, until I went to one of the seminars held in conjunction with the fair. Though I don’t recall the speaker, I do vividly remember Mildred Mottahedeh (1908-2000), founder of the luxury porcelain supplier Mottahedeh and Company.” The rest is history. We developed a rewarding friendship and saw one another at least several times a year until her death. She was an inspiration and mentor.

Learning to say “goodbye” – plans for your own collection?

Saying goodbye is not sweet sorrow. It is more brutal – like losing an arm or leg and being beaten with the bloody end. Until recently, the latter is the way I was feeling. Then, quite suddenly, an idea occurred to me that was pleasing because it meant my collection could help others not only by giving buyers joy but also the less fortunate: Sell at auction, enjoy the catalog that accompanies the sale, sponsor an associated educational seminar and give the proceeds to a charity. This idea felt good; losing my collection to a higher cause. Whether it will ever happen is quite another thing. Right now, it is just an idea.

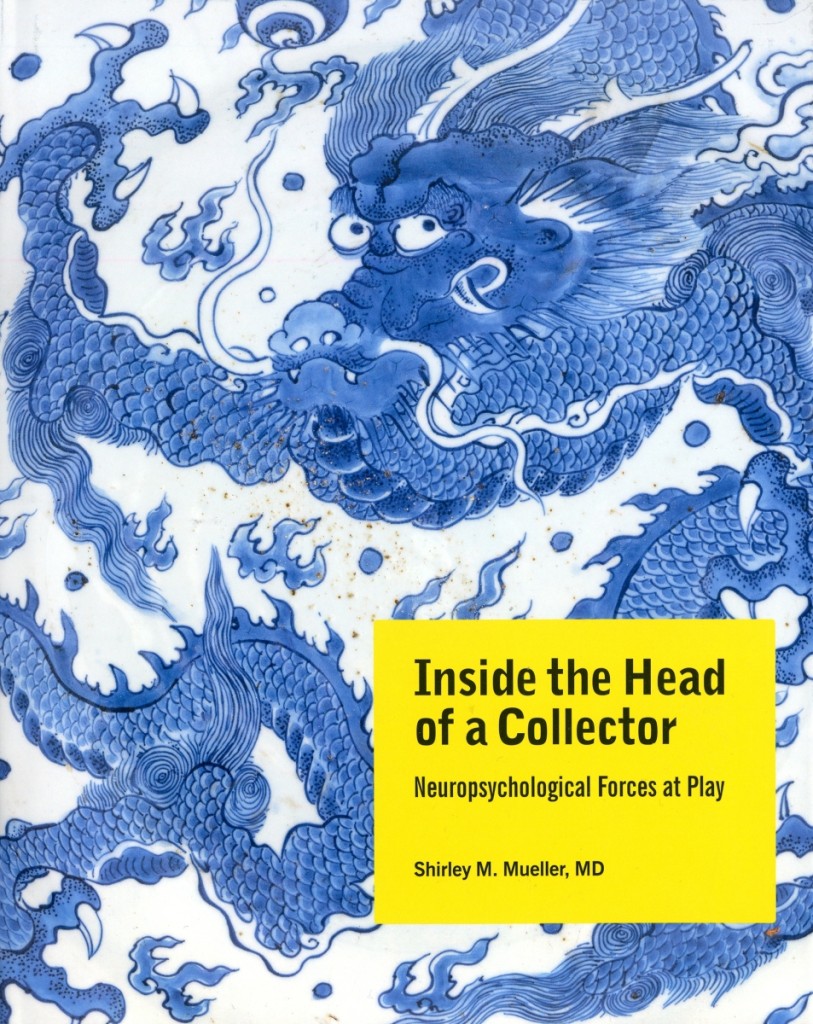

Inside the Head of a Collector: Neuropsychological Forces at Play by Shirley M. Mueller, MD, ISBN:978-0-9996522-7-5 can be obtained through Amazon or at the Metropolitan Museum of Art bookstore in New York City and other assorted bookstores throughout the United States.

– W.A. Demers

-688x1024.jpg)