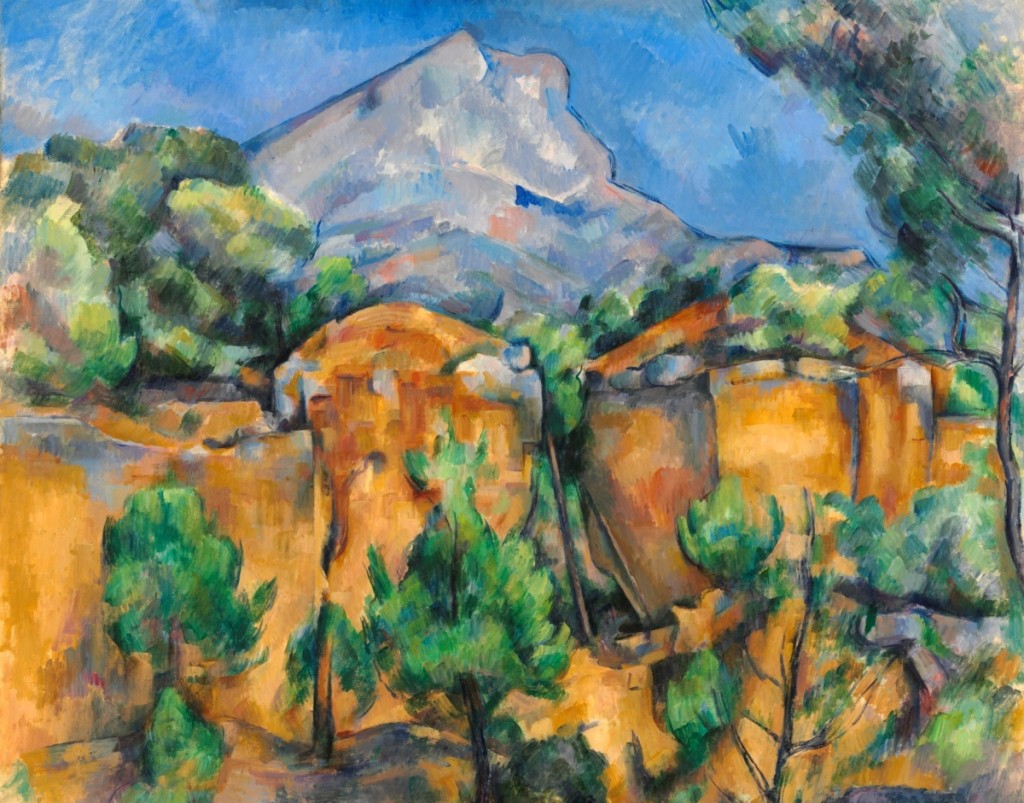

“Montagne Sainte-Victoire seen from the Bibémus Quarry” by Paul Cézanne, circa 1897. Oil on canvas.

The Baltimore Museum of Art, The Cone Collection.

By Jessica Skwire Routhier

PRINCETON, N.J. – Formative experiences have an enduring power. They shape the way that creative people come to view the world, and they become touchstones those people refer to over and over again, in whatever form their creative and intellectual expression takes. Certainly, this was true of Paul Cézanne, the French modernist painter whose work was the hinge between Impressionism and Cubism. Although much of his career played out in Paris, his primary artistic concern remained the landscapes of his native southern France, marked by millennia of geological change, centuries of human industry and inquiry, and the friendships that developed and grew within that rare and endlessly fascinating place. Focusing on a select group of paintings and watercolors that unite these concerns, “Cézanne: The Rock and Quarry Paintings” is at the Princeton University Art Museum (PUAM) from March 7 through June 14, 2020.

Cézanne himself was a formative experience for the exhibition’s curator, John Elderfield, who until recently served as Princeton’s Allen R. Adler, Class of 1967, Distinguished Curator and lecturer at PUAM, and who is also chief curator emeritus of painting and sculpture at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. “I first became involved with Cézanne back in June of 1971,” he remembers, “when Artforum had asked me to review an exhibition of his works.” He then “came to know well” other Cézanne scholars, including Lawrence Goring and John Rewald, and over time took on the mantle of “Cézanne expert” himself, writing about him extensively and ultimately curating a major show of portraits at London’s National Portrait Gallery in 2018; the Telegraph called it “The art exhibition of the year.” Cézanne, naturally, was a focus of Elderfield’s teaching at Princeton, and the present exhibition was suggested by PUAM director James Steward as a way to mark the end of his tenure there.

Cézanne’s story, too, involves an enduring network of friendships between people who shared and supported one another’s personal and professional interests. Much has been written about the friendship between Cézanne and the great French writer and intellectual Émile Zola, who were childhood playmates in Aix-en-Provence and, together with another friend, the future scientist Jean-Baptistin Baille, called themselves the “trois inséperables” (three inseparables). But this exhibition and its excellent accompanying catalogue mine the surface of these friendships a bit further, adding a fourth member to the group – the somewhat younger Antoine-Fortuné Marion, who became a renowned geologist and paleontologist – and showing how the ancient, quasi-mythical landscapes in which these four young men grew up was a conduit for their professional achievements and the background, literally and metaphorically, for the lasting circle of intellectual inquiry that they built up around them.

The south of France is, in a meaningful sense, the birthplace of painting itself. Although the paintings on the walls of the Lascaux cave system would not be rediscovered until 1940, long after Cézanne’s death in 1906, excavations of prehistorical cave sites were already underway in his youth, helping, among other things, to spark the young Marion’s interest in paleontology. Cézanne himself is known to have pondered “those first men who carved their dreams of the hunt on the walls of a cave,” leaving their mark on a natural structure that had long preceded them and would endure long after they themselves were but a pile of bones on the cave floor. Such intertwined histories of geology and human life are imprinted upon the landscape of the region in a million different ways-paleolithic rock formations and ancient Roman arches and aqueducts dot the landscape of Provence. Everywhere in the landscape of southern France, from the sheared sides of Aix’s Montogne Saint-Victoire, to the glacial stones of seaside cliffs, to the scraped-away edges of rock quarries, there is evidence of human and geological change over time, a subject that would fascinate all four of the inséperables, in different ways, throughout their lives.

The nearby town of L’Estaque, near Marseille on the Mediterranean coast, was familiar to Cézanne from childhood, when he vacationed there with his family. It was a welcoming and familiar environment in which to experiment with the daring palette-knife painting technique he had developed in Paris, where he had moved in 1861 with Zola’s encouragement. While Cézanne’s earliest L’Estaque works are more traditional views of the town and the harbor, he soon turned to the less cultivated, more primeval natural formations that lay just inland. The glacial rock formations, interspersed with low-bush pines and wild rosemary, provided appealing subject matter for his new expressionistic style and allowed him to continue a tradition of painting humble, overlooked landscapes that the earlier generation of Barbizon School painters had pioneered. Cézanne himself is thought to have worked alongside the Barbizon painters in their favored location of the Forest of Fontainebleau, outside of Paris, in the late 1860s.

It was around the time of Cézanne’s earliest L’Estaque paintings that his friendship deepened with Marion, who was studying and performing archaeological excavations in and around Provence at this time – and also creating the occasional landscape painting. The two men met frequently, often with other friends like Baille, to discuss their respective endeavors and their mutual interests. One of the gems of the Princeton show is a sketchbook, dating from the years 1857 to 1871, which includes drawings and notations by both Cézanne and Marion. Both men were interested in the shapes and layers of the rocks and earth that surrounded them; both used the motif of a bunched-up cloth – seen scattered with fruit in many of Cézanne’s mature still lifes – to replicate and explain the shapes and formations of mountains and other landscape forms.

These were among the ideas and influences that Cézanne brought back to Paris with him after the fall of the Paris Commune, in the spring of 1871, and the end of the privation that had begun with the Siege of Paris the year before. But for all that he was a modernist par excellence, Cézanne was no painter of modern life like many of his colleagues were – so the city itself held little appeal for him as subject matter. He soon found himself back at Fontainebleau, where he worked extensively in the 1880s and 1890s. Here are silver-violet boulders, composed of sharp angles slicing the sun-struck surfaces apart from those in shadow, set against patches of scrub pine needles interspersed with blotches of sky. Here we see Cézanne’s characteristic style take place, one that Elderfield describes as being preoccupied with the structure of a place. All those talks over sketchbooks in Provincial cafés, all those walks through ancient landscapes with his scientist-friends, gave him a deep understanding of how these landscapes were made, how they exist in space today, and how they continue to evolve. Cézanne’s paintings, with his characteristic taches – “spots,” in English, here referring to individual brushstrokes – of color, convey his knowledge of that structure, that history, even as the act of painting itself becomes his way of knowing it more deeply.

Elderfield sees this in particular in Cézanne’s paintings of the abandoned Roman Bibémus quarry in Aix. The site is richly historical, both in terms of human history – it is believed that the ancient Romans were the first to excavate it for its limestone, a practice that continued off and on well into the Nineteenth Century – and personal history, for the quarry was a frequent haunt for the young Cézanne and his boyhood friends. This intimate knowledge of the place – from physically exploring its peculiarities as a child, to coming to better understand its science and geological makeup, thanks to knowledgeable friends, as an adult – surely informed Cézanne’s many mature paintings of it. At Bibémus, Elderfield notes, “the geological strata were more visible to be painted than with other subjects,” and thus all but unignorable for an artist so interested in the physical reality that undergirded his painted images.

“L’Estaque” by Paul Cézanne, 1879–83. Oil on canvas. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. The William S. Paley Collection.

Cézanne’s taches; his angular, proto-Cubist forms; his thickly impastoed palette-knife work – all these underscore the materiality of his process, and the way that his building up of an image on canvas resonates with the building up of a physical space over time (as well as its later deconstruction, in the case of Bibémus, by human beings). But materiality comes into play in his palette, as well. As Elderfield and Ariel Kline write in the catalogue, “the red ocher hue [in the Bibémus paintings] is a reminder . . . that the rich red and ocher pigments that Cézanne used in his paintings of the areas likely derived in part from local sources. In this way, the material means as well as the subjects of such Bibémus paintings had local connotations.” The very earth was in the paintings; they were made of the same stuff – and so, as Cézanne and his friends discerned, to know and be involved in the study of one was to better understand the other.

The exhibition is organized roughly along these chronological, geographical lines: L’Estaque, Fontainebleau, and then Bibémus (those who can’t conceive of a Cézanne show without the Montagne Saint Victoire will be relieved to see it rise from the background of more than one Bibémus painting). The concluding section is devoted to the Château Noir, a rather mysterious, never-completed mansion constructed from Bibémus limestone. The grounds of the château were another favored childhood destination for the trois inséperables, not just for the house itself but also for the surrounding grottoes that were of the type where Marion would one day lead archaeological excavations. Cézanne rendered the rocky mouths of these caves in oil and watercolor, creating colors, shapes and effects that are both utterly convincing and otherworldly, compelling more than one scholar over the years to find in them the mythical creatures of Provence’s Roman past, or at least anthropomorphized representations of the unconscious.

Cézanne, classically educated in Greek and Latin, would certainly have understood such allusions and recognized why viewers were eager to see them in his artwork – but it is unlikely that he set out to paint them as such. He thought of such tropes as belonging to literature and not the visual arts. “Yes, you have your metaphors, your comparisons,” he once argued to the writer Joachim Gasquet. “But for us, we have only our colors; what is visible.” Therefore, while “it would be foolish to imagine that Cézanne could not have seen a gigantic body in a rocky landscape,” Elderfield writes, “the point is that he could not permit himself to specify anything other than the rocks ‘as they are in nature.'” It is lucky, then, that for Cézanne, nature itself was not only science and structure but also myth and miracle, the observable here and now but also the whole history of time writ large, and that every work of art he created is a small attempt to document and honor that vast phenomenon.

Princeton University Art Museum is located on Elm Drive. Admission is free. For hours and information, call 609-258-3788 or visit https://artmuseum.princeton.edu/art/exhibitions/3447.