In the last year of the Eighteenth Century, sailors in Salem, Mass., operating out of one of the largest and premier ports in America, banded together under the Salem East India Marine Society to combine their resources, improve their trade, build upon their knowledge, to take care of one another’s families, and for all of our sakes, to build a museum. Two hundred and twenty-one years later, we have the Peabody Essex Museum (PEM). The museum’s associate curator George Schwartz has penned a study on its transformations through a long and storied history in his book Collecting the Globe: The Salem East India Marine Society Museum. We sat down with Schwartz to learn about the institution’s past, its founders and what its mission symbolized for early America.

How did the Salem East India Marine Society Museum originate?

In the early days of the United States, marine societies covered the eastern seaboard from Maine to South Carolina (and Salem had two!). All adhered to one major principle: the goal of providing relief to the widows and families of sailors who “go down to the sea in ships, and nevermore return” and to sailors who had fallen on hard times. In addition to benevolence, many marine societies supported improved navigation in and around their home ports. Marine societies were comprised of local captains and supercargoes (the business agent on board a ship) who paid an initial membership fee as well as dues at each meeting, which were invested to support charitable purposes and maritime endeavors.

At the dawn of the Nineteenth Century, as Salem expanded its international presence, 22 Salem captains formed the East India Marine Society. To distinguish themselves from all other American marine societies, including the Salem Marine Society founded in 1766, the East India Marine Society limited membership to Salem supercargoes and masters with worldly nautical cachet: those who sailed near or beyond the Cape of Good Hope or Cape Horn. The society was also founded to promote “a knowledge of navigation and trade to the East Indies” and, above all, “to form a museum of natural and artificial curiosities;” today, the Peabody Essex Museum.

Who were its main figures?

The East India Marine Society’s strict membership qualifications created an exclusive maritime organization, one that attracted the pioneering mariners in the town. Among its early members were those who had opened American trade across the globe, such as Benjamin Hodges, who arrived in Salem with tea from Canton in 1790 while commanding the brig William and Henry; Jacob Crowninshield, who brought the first elephant to the United States on the ship America in 1797; and Jonathan Lambert, who had taken the brig Hope to Mozambique in 1789 and later became the self-appointed ruler of Tristan da Cunha in 1811. Principle among them all was Nathaniel Bowditch, a veteran of the East India trade as both supercargo and master, who was the most famous of early New England scientists who was elected to every major American and European scientific society during his lifetime. He is best known for his New American Practical Navigator, an invaluable tool for generations of mariners that is still published.

What were its ambitions?

The mariners who formed the East India Marine Society wanted to reflect Salem’s new global standing in the early 1800s as the sixth largest port in the United States, accounting for five percent of the nation’s per capita income. They required all members to carry a separate logbook on their voyages in order to “collect such facts and observations as may tend to the improvement and security of navigation.” They created an archive of nautical information that predated any governmental repository and was unsurpassed in the country in the early Nineteenth Century. These volumes were also an important resource for the society members’ commercial pursuits, thus blending scientific knowledge with economic gain. Members’ contributions to navigational science helped elevate the institution and the museum to the national stage in the early Nineteenth Century.

The East India Marine Society also distinguished itself from many collecting institutions of the day by instructing members to obtain objects for the museum during their voyages. This unique aspect of the society’s mission was an outgrowth of Salem’s commercial maritime trading networks, a rational curiosity that characterized scientific exploration in the new republic and sailors’ predisposition to acquire objects from their voyages.

What was their criteria to acquire something?

The East India Marine Society built upon a maritime culture of recording and collecting by codifying the practice for its members. On the frontispiece of the blank society journals given to members to fill out on their voyage were directions to note “[w]hatever is singular in the manners, customs, dress, ornaments, &c. of any people…deserving of notice.” At the bottom of the page were guidelines for collecting natural history objects: “There should be collected, for the museum, specimens of various kinds of vegetable substances, earths, minerals, ores, metals, volcanic substances, &c. There should also be preserved such parts of birds, insects, fish, &c. as serve most easily to distinguish them, and if no part can be preserved, a description of any that are remarkable, may be given.” These directions – the first printed evidence of the society’s interest in creating a museum – were common parlance for European naturalists on voyages of discovery in the Nineteenth Century but were unusual for American commercial voyages. The last section of instructions to society members contained specific directions for collecting objects for a museum collection: “Inquiry should be made for any remarkable books in use among any of the eastern nations, with their subjects, dates and titles. Articles of the dress and ornaments of any nation, with the images and objects of religious devotion, should be procured.” This final passage, among the earliest American museum collecting strategies, aided members in building an institution reflecting their global trading networks.

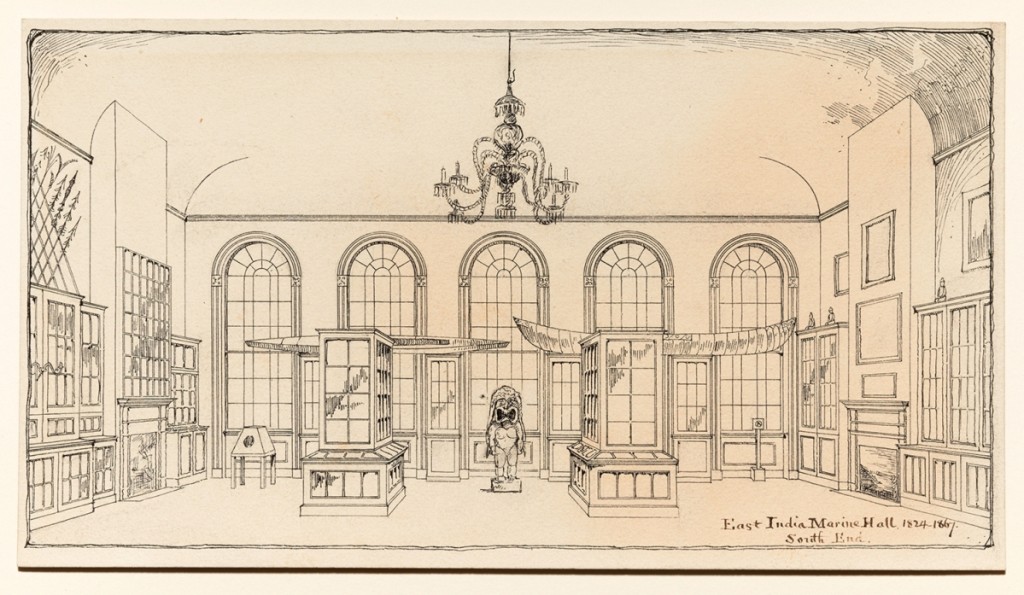

James Henry Emerton, “East India Marine Hall, 1824-1867, South End,” 1879, ink on paper, 6½ by 11¾ inches. Peabody Essex Museum Collection, M303.2. ©2016 Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, Mass. Photography by Kathy Tarantola.

Did they focus their collecting in any one area?

While the society promoted objects “found beyond the Cape of Good Hope and Cape Horn,” the scope of the collection was truly global. Of the over 6,400 objects acquired during 68 years of collecting, approximately one-third were from regions other than those beyond the capes. They included Western paintings and sculptures, objects from native North and South American cultures, Near Eastern antiquities, and American and European prints. From 1799 to 1867, more than 330 members fulfilled the Society’s objectives, donating man-made and natural objects collected from many ports of call around the globe, from Pacific island sculptures, to flora and fauna, to Western art.

How did they set about accomplishing acquisitions?

The East India Marine Society amassed a wealth of material culture during the years before the Civil War, but not solely through the work of its members. While they established an internal impetus to collect for the museum, almost half of the objects accumulated between 1799 and 1867 were donated by mariners who were not members, trading partners abroad, the lay public, and many others who were “friendly to the institution” – attesting to the international networks formed by American maritime trade. In addition, the East India Marine Society commissioned works from local artists to fill perceived gaps in their institutional narrative. Collecting was a communal effort and represented a vast acquisition network. In this way the museum was unlike any other in the antebellum United States. Salem mariners’ pioneering voyages to the Pacific Islands and the East Indies in the early days of the new republic – during which they reached ports on all of the continents except for Antarctica – provided the means for acquiring most of the objects in the museum. In the first decades of the Nineteenth Century, the collection reflected both Salem and US overseas trade.

What are the key moments when the museum progressed?

In the early Nineteenth Century, during the height of Salem’s maritime clout, the East India Marine Society’s membership grew to 140 members, and a vast assortment of objects poured into the museum. During the first few months of the society’s founding in 1801, members trading in the Pacific donated 35 objects. Within a decade, the collection grew almost 20 times in size, and it more than doubled during the following ten years, reaching more than 2,000 objects by 1821. The East India Marine Society was immediately recognized as a novel institution in the United States due to its unique attributes. Unfortunately, Salem’s maritime fortunes would not be as long-lived as the East India Marine Society’s museum. As a result of the Embargo Act of 1807 and the War of 1812, Salem merchants had started to move their businesses to Boston, New York and other larger harbors. The city never attained its pre-embargo economic prestige, although it remained a busy port until the 1840s. The East India Marine Society Museum, though, continued to have national influence and grow. The collection more than doubled by the end of the 1820s, and the highest annual visitation occurred during the next two decades. In the 1830s, Salem experienced a great intellectual awakening, and the East India Marine Society Museum benefited from the city’s transformation with increased attendance from a wide swath of American society.

What kinds of exhibitions were they putting together? Did their style change over time?

The museum was an organized display of the natural, cultural and spiritual world bound by the sea and open to visual inspection through the efforts of the American maritime trade. The East India Marine Society did not collect objects as a means to classify other cultures or races, nor were these objects simply tools for obtaining global knowledge. Rather, this vast array of material culture was displayed as the society’s expression of what it meant to be an American; an American identity tied to the sea. The objects on display denoted both Salem and the new nation’s position in the world. The displays were organized so that visitors could recreate a voyage around the globe. Upon entering the museum, visitors would have felt surrounded by the sea. They would have seen a birchbark canoe and a sealskin kayak perched above floor cases; a 6-foot, 7-inch sculpture of the Hawaiian god Kūka’ilimoku that had once stood in front of a coastal heiau, or temple, of King Kamehameha I; an early Nineteenth Century plaster-cast copy of the classical sculpture known as the Laocoön Group depicting the Trojan priest and his sons wrestling with great sea serpents; life-size portrait figures of the most prominent Chinese and Indian agents trading with Americans in the first half of the Nineteenth Century; fireboard paintings of international and local ports by Michelle Felice Cornè and another local artist, Samuel Bartoll; busts of American patriots, European philosophers and classical deities; portraits of the Mumbai merchant Nusserwanjee Maneckjee Wadia and the Cantonese merchant Eshing – both trading partners of society members – exhibited alongside maritime heroes such as Captain James Cook; busts of American military heroes next to Southeast Asian religious sculptures; portraits of revered mariners, shipowners and society members, as well as Eighteenth and Nineteenth Century versions of Renaissance paintings collected during local Salemites Grand Tours; and spears and clubs from the Pacific Islands. Natural history specimens were integrated into the room with the rest of the collection and organized by type in their own cabinets, and large natural history specimens related to the sea took prominent positions in the museum such as two lower jaws of a sperm whale and Neptune’s cups.

Following a Linnaean system for categorizing natural and artificial curiosities, an unidentified visitor in 1830 was “much gratified, while on a late visit to Salem, to witness the many alterations and improvements which have been made [to the Hall] within a few years,” which the person believed were extensive. The visitor also noted that “many curiosities in nature and of art, are continually increasing its well selected assortment; and they are all classified in such good taste and with so much judgment, as to produce the most happy effect.” This patron declared “unfeignedly” that “East-India Marine Hall… contain[s] within its galaxy of beauties – the quintessence of all the Museum and Theatres, that adorn the cities of the United States.” In 1838, some displays were rearranged “in order to bring together such articles as bore a resemblance to each other or were used for the same purposes in the economy of life by the different nations, such as the cooking utensils, shoes, hats, warlike instruments etc, etc.”

Model of United States Frigate Constitution, about 1812. Wood, paint, cordage. 59 by 77 by 29½ inches. Gift of Commander Isaac Hull. Peabody Essex Museum Collection, M47. ©2014 Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, Mass. Photography by Walter Silver.

What was the impact of the society on the early Massachusetts public?

At a time when the country was filled with Barnum-esque oddity museums, the East India Marine Society Museum was one of the most influential collecting institutions in the United States during the Nineteenth Century. One could essentially circumnavigate the globe through the objects presented within the walls of the historic East India Marine Hall. While filled with complexities, the society sought to present visitors with an understanding of the world through the display of objects collected via global exchange. These expressions of cultural identity had a profound impact not only on Salem residents, but also on the diverse American audience that came from across the country and the globe to visit the museum, making distant shores as well known as provincial towns. Through the museum and its collection, the society brought the world back home to its native town. The complexities of this mission, the society and the dualities that existed in the country at the time, however, created something more expressive of a nascent American identity.

Tell me your favorite thing the Salem East India Marine Society ever did.

During the first two decades of the Nineteenth Century, the East India Marine Society members would parade through the streets of Salem with objects from their collection to celebrate their anniversary: a public display of their worldly mercantile success through global objects. One of these objects was a six-foot-long model of the USS Constitution made by the ship’s crew around the time of its famed victory over the HMS Guerriere during the War of 1812. The crew had presented the model to the Constitution’s commander, Isaac Hull, and he quickly donated it to the society in 1813. They also used the Constitution model at other events. In the fall of 1813 it was brought to Hamilton Hall on Chestnut Street for a banquet in honor of then-commander Commodore William Bainbridge. A salute in Bainbridge’s honor was fired from miniature guns on the model and damaged the rigging. Without a model maker close at hand to repair it, the society turned to British prisoners of war who were being held in a prison ship in Salem. They repaired the Constitution, and then presented the society with a bill for their services! Years later, the Boston Daily Globe remarked, “[T]he British prisoners…got a little pocket money while forcibly reminded of the very cause of their imprisonment.”

In what noticeable ways does the Salem East India Marine Society Museum exist within the Peabody Essex Museum if one were to visit today?

The East India Marine Society left a substantial institutional archive currently housed at the PEM’s Phillips Library and almost a third of the society’s collection still exists. In addition, East India Marine Hall, the society’s first permanent home opened in 1825, has been installed in a manner akin to its appearance in the Nineteenth Century. It is unheard of to still have the original archival material, the collection and the permanent home for an early American institution, a place where visitors today can walk in the same space and see the same objects as their counterparts did over the past 200 years. By visiting the museum today, you can have a similarly unique experience of walking in the footsteps of history. You are looking at objects that people from all walks of life, in America and across the globe, looked at. For Twenty-First Century visitors to the PEM, this experience illuminates the interconnected global world that existed in the Nineteenth Century, and the place of Americans – culturally, intellectually, and politically – within it.

Collecting the Globe: The Salem East India Marine Society Museum, is available to purchase from the PEM shop’s website; UMASS Press; and it can be purchased from Amazon, which has a Kindle version.

-Greg Smith