By Laura Beach

COLCHESTER, CONN. – “Dear Wendy and Brock,” the 1996 letter from Zeke Liverant to Winterthur Museum’s then curator of furniture, Wendy Cooper, and deputy director, Brock Jobe, began. Enclosing as proof copies of photographs taken on a snowy Connecticut sidewalk in 1958, the proprietor of Nathan Liverant and Son Antiques described in detail his acquisition of a Newport china table with a pierced gallery top in Providence 38 years earlier. Made in the last decade or so of the Eighteenth Century, most likely by John Townsend, the high-style piece remains a highlight of Winterthur’s collection.

The letter, meant to enhance Winterthur’s understanding of the table’s history of descent, was significant in another respect, as well. It flatly contradicted the account of the table’s discovery told by New York dealer Harold Sack in his 1986 memoir American Treasure Hunt: The Legacy of Israel Sack. At one time such an act of defiance by the Liverants – who for decades sold many of their best finds to Israel Sack, Inc., and who counted Harold’s brother Albert as a close family friend – would have been unthinkable. But such an explicit correction of the record – previously recounted in an understated way in this publication and in a 2010 piece by Briann Greenfield for the journal Connecticut Explored – symbolically marked the Liverants’ ascendance to the pinnacle of their profession.

To be told in a forthcoming history of Liverant Antiques by Kevin J. Tulimieri, an avid researcher and the firm’s resident writer, the family business has enjoyed distinct phases under three generations, each ambitious to elevate its standing. A Russian Jewish immigrant who arrived in New York unaccompanied in 1907, Nathan Liverant (1890-1973), in addition to working as a furrier and livery driver, traded in scrap metals and used household furnishings before carving out a niche in antiques around 1920. By 1930, he occasionally organized auctions in and around Colchester, a melting-pot community of immigrant farmers and merchants that Nathan appears to have first visited around 1915.

-1024x684.jpg)

Nathan Liverant arrived from Russia in 1907 and by 1920 established himself as a dealer in used and antique furniture. He also conducted the occasional auction, as this 1941 photo illustrates.

Born in Colchester, Nathan’s son Israel Ezra Liverant (1916-2000), called Zeke, was a charming, charismatic storyteller and industry sage who commanded a rapt audience at antiques shows around the country and in the Liverant shop, a former Baptist Meeting House on South Main Street in Colchester that has been the company’s headquarters since 1949. Aside from the addition of two large bay windows, kept stocked with an alluring array of high chests of drawers, dressing tables, candlestands and tea tables, the imposing Greek Revival structure of 1835 remains largely unaltered.

After attending Colchester’s historic Bacon Academy and serving, as his brothers did, in the US military during World War II, Zeke resumed work with his father, a naturalized citizen who registered for the draft in New London, Conn., in 1917. According to family lore, Zeke was still a boy when he identified in a heap of secondhand silver a caster by the New York City silversmith Jacobus Vander Spiegel (1668-1708). With Nathan’s permission, Zeke saved it for a buyer who subsequently agreed to pay the lavish sum of $100 for it. While Tulimieri has yet to locate the piece, the company’s account books record what may be a resale of the caster to Israel Sack, Inc., in 1958 for $1,200.

As the story suggests, Zeke was impatient with his self-made father’s cautious investment approach. The recognition Zeke hungered for occurred almost overnight. On July 27, 1953, Life magazine published “Zeke the Seeker,” a profile prompted in part by the new zeal for antiques among middle-class Americans in the postwar era. Mail arrived by the box full to Liverant Antiques in response to the article. Zeke answered many of the letters personally.

Offended by the word “picker,” Zeke’s wife, Sylvia, suggested that writer Robert Wallace use the word “seeker” instead. Seeker or picker, the story captured the essence of the business as Zeke lived it. Zeke had a talent for meeting people and discovering their family connections. His memory was “uncanny” and his knowledge “encyclopedic,” says Tulimieri. Zeke told Wallace that he put 2,000 miles a month on his station wagon, making house calls and tending to relationships that, carefully cultivated, bore fruit over time. Knowledge and patience were key. The growing market for antiques produced more buyers, but also more competition. Zeke told Wallace, “The day of the ‘sleeper’ or fantastic bargain is almost dead and has been since the ’30s.”

Gigi and Arthur during set up at New York’s Winter Show. Of his “Rookie” cap he has explained, “You never stop learning in this business.”

In reviewing the multivolume set American Antiques from Israel Sack Collection, Tulimieri has identified dozens of objects the Liverants sold to the Sacks. Surviving in the company’s files are Zeke’s meticulous notes on where, when and from whom objects were purchased. Zeke kept an album of extraordinary discoveries called “Great Finds.” Most famous among them is a group of needlework by Prudence Punderson (1758-1784). Given to the Connecticut Historical Society by Newton C. Brainard in 1962 and illustrated on the cover of the 2010 book Connecticut Needlework: Women, Art, and Family, 1740-1840 by Susan P. Schoelwer, the most memorable of these embroideries is “The First, Second, and Last Scene of Mortality,” Punderson’s cradle-to-grave self-portrait in silk on linen. It provides a window on women’s roles, domestic interiors and race relations around the time of the American Revolution.

For the past two decades Liverant Antiques has prospered under the direction of Arthur S. Liverant, a born organizer who through his energetic efforts to educate collectors and rally colleagues has become an essential figure in the field, a man committed to the ideal of American life as reflected in its art and artifacts. Born in Colchester in 1949, Arthur grew up with sisters. Perhaps influenced by their mother, a person of “huge heart” who taught her children to be generous, Arthur’s siblings Abby and Linda pursued careers in the helping professions. A youthful enthusiast of the cartoon series Chip ‘N Dale, from whence he is said to have learned his first word, Arthur, in addition to jobs at the local pizza joint and gas station, as a youth helped out in and around the shop, accompanying his father on house calls when Sylvia Liverant needed a respite from her active son.

“The first thing I learned to do was fold packing blankets. To this day I have a fetish for it,” says Arthur, who graduated to polishing brass, cutting the lawn outside the shop and in other ways demonstrating his responsibility. Like other important firms of the day, Liverant Antiques employed a cabinetmaker. Ukrainian immigrant Konstantin Haliw walked into the shop looking for work in 1948 and stayed until his retirement. “Konstantin was one of my best teachers. He was only 5 foot, 2 inches, nothing but leather and iron, but he was a remarkable human being. Among other things, he made coffins for the Russian front during World War II and arrived here after a Lebanon, Conn., farmer sponsored his resettlement. My grandfather, who spoke Russian and Ukrainian, gave him a workbench and some tools. Konstantin taught me about wood and construction, which fascinated me. He even helped me construct a school project identifying mahogany from different places in the Americas,” Arthur recalls.

Weekly educational forums bring people in the shop during the spring and fall. Here, Kevin and Arthur hoist a chest of drawers from Litchfield County, Conn., giving guests a view of its distinctive, cross-braced construction.

Drawn by the reputation of its Division I soccer team, Arthur enrolled at Hartwick College in Oneonta, N.Y., officially joining his father in business in 1971, soon after earning his degree. “I had huge respect for my father, with whom I worked right up to the day he died. I appreciated him as a great teacher, and he admired my work ethic. We had differences of opinion but never fought. I inherited his friendships as well as his grudges,” confesses the dealer, who remained especially close to Albert Sack (1915-2011), whom he regarded as a “surrogate father” after Zeke’s death.

One Sunday morning Arthur visited New London’s old Lighthouse Inn, drawn there by the reputation of resident artist Harris Rodvogin (1897-1998). There he met Georgeanne Horr, called Gigi. The recent Paier College of Art graduate was moonlighting in a Waterford, Conn., body shop at the time, touching up paint on cars. A gifted colorist who infuses the landscapes of everyday life with mystery and magic, Gigi, the company’s creative director and videographer, brings flair to all Liverant productions. Married since 1974, Arthur and Gigi preside with humor and warmth over an affectionate brood that includes their two adult daughters, Hannah and Samara, and grandchildren Emmeline, Theodore, Scarlett and Molly.

Arthur describes Liverant Antiques as an ensemble effort. Helen Boule has managed the company books for more than a quarter century, and anyone who has done business with the firm has likely spoken or corresponded with Ellen Sharon, a history buff who chairs both the Colchester Historic District Commission and the Connecticut Humane Society and makes Liverant Antiques run efficiently.

Whether on a house call or at an antiques show, Arthur is rarely without Tulimieri, whose froth of beard and long cascade of curls call to mind Pennsylvania dealer Joe Kindig Jr (1898-1971) or the sandal-clad Ohio dealer G.W. Samaha. Originally from Boston, Tulimieri grew up in Glastonbury, Conn., fascinated by the “odd contraptions” his grandfather stashed in his old dairy barn. “I just always loved history,” says the dealer, who attended art school in Hartford, Conn., where he was a schoolmate of Antiques Dealers’ Association of America (ADA) president Steven S. Powers. In pursuit of the woman who would become his wife, Tulimieri briefly moved to Maine, where he found work in nearby New Hampshire refinishing furniture for a second-hand shop. “I was out in an unheated garage all winter wearing a ski jacket and wool hat. I listened to ‘Super Fly’ by Curtis Mayfield over and over on an eight-track player supplied by the owner,” he recalls.

Back in Connecticut, Tulimieri worked for Hometown Journal in Moodus, progressing quickly from photographer to reporter to editor. “When news was slow, which was often, the previous editor filled in with local history. As editor, I moved history to the front page,” says Tulimieri, whose interest in the past led him to Zeke Liverant, with whom he quickly formed a bond. With Liverant Antiques since 1998, Tulimieri follows his scholarly inclinations, providing comprehensive reports to clients and contributing articles to journals. He says, “My main interest is the last piece that came into the shop, and I enjoy the interaction with my dealer colleagues, curators and collectors, so many of them passionate, knowledgeable people. Working for Arthur is a dream come true for me.”

A framed broadside at Liverant Antiques advertises an auction the company organized in 1930. “This will be a Clean Sale. There will be no By-Bidders or Boosters,” the poster says, asserting the ethical stance by which the company has long lived. As Kevin says, “Here it’s about objects and the truth; about honesty, integrity, history and knowledge. It all wraps together and is the key to this business’s success.”

Arthur enjoys sharing his knowledge, whether in one-on-one tutorials in the shop and at shows, or at the weekly forums he presents with Kevin at the shop each spring and fall. Edited and posted by Ellen, video clips from the forums, on hold because of the COVID-19 crisis, are available on Liverant Antiques’ YouTube channel. Topics range from the basics of Connecticut furniture to the intricacies of inlays to Arthur’s reminiscences of the local hotdog stand Harry’s Place and its place in Colchester’s robust political culture.

Although he has never run for political office himself, Arthur has devoted himself to building stronger communities, whether among antiques dealers, at his synagogue or in the town of Colchester. Zeke and Arthur took leading roles in founding the ADA in 1984 and, like his father before him, Arthur has pledged himself to its ethical and educational mission. He pushed for the ADA’s annual Award of Merit, first presented to Albert Sack in 2002, and is deeply involved in its yearly presentation, a rewarding but time-consuming project he likens to annually hosting a bar mitzvah.

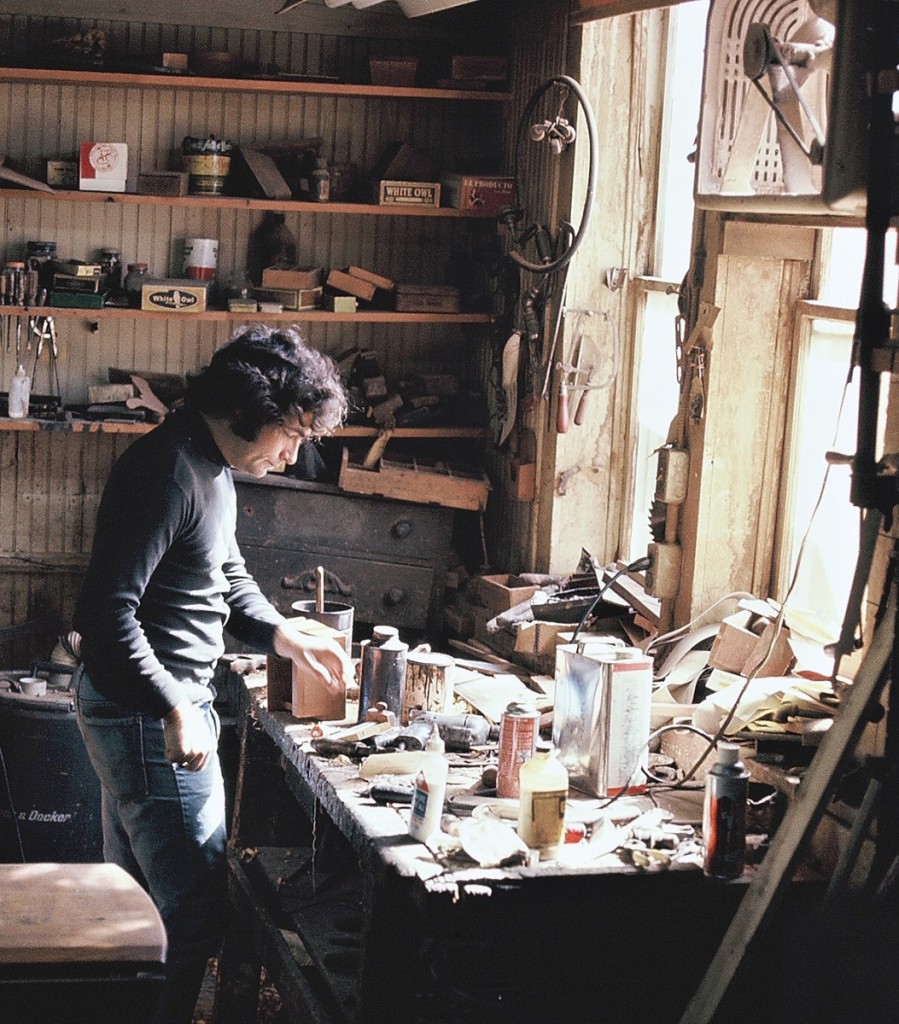

Arthur, here in the workshop around 1976, learned woodworking fundamentals from Liverant Antiques’ longtime cabinetmaker, Konstantin Haliw.

Two of Arthur’s proudest achievements have nothing to do with the antiques business. He stood up to powerful local business interests to save Colchester’s 1809 Sparrow house from demolition, first enlisting the help of state and local politicians, then extending himself financially to buy property. “We started fixing the house up and the town took notice. A buddy came to me and said, ‘You know what people are saying? They’re saying Arthur Liverant has a big mouth, but he finally put his money where his mouth is. Everyone is thrilled.’ A developer approached me with an offer to buy the house and make it a medical center but leave its exterior intact. Aside from a bill for $1,200 that came in after we closed, I broke even.”

Arthur chokes up when he discusses Colchester’s School for Colored Children, as it was originally called, and his drive to recreate the historic structure, which educated non-white students in the first decades of the Nineteenth Century. Colchester’s Bacon Academy did not admit students of color until 1848. “I told Gigi, ‘I just have to do this.’ She agreed, and I persuaded my sisters and their spouses to take part,” says Arthur, who when we spoke was reading The Color of Water: A Black Man’s Tribute to His White Mother by James McBride. He adds, “Colchester was ethnically diverse when I was growing up, and everyone got along. What’s happening now breaks my heart.”

Long experience has supplied Arthur, who has a lively sense of humor, with a repertoire of entertaining stories, many involving great discoveries. From a house in Farmington, Conn., came a japanned high chest of drawers and dressing table, the former now in the collection of the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. Houses in New London yielded a major Charles M. Russell sporting painting and the only known musical tall case clock by Simon Willard, now at the Willard House and Clock Museum.

These stories are best told by Arthur himself. One, shared here, illuminates the central paradox of a century-old business: commerce may be cultivated over generations but deals are struck in the moment and often require ingenuity and daring to consummate. Forty-nine years ago, Zeke took Arthur with him on an impromptu house call to visit the descendants of Thomas Stanton, an English immigrant who in 1670 built a once grand but now dilapidated house near Stonington, Conn.

The view from the mezzanine at Nathan Liverant and Son, which maintains a large inventory of antique American furniture and accessories.

“The house from the outside was unpainted and forlorn. You could lose your rear end on the rocks in the driveway. Inside, at least from what we could see, it was a real time warp. My father stopped by regularly but was never allowed past the first two rooms,” Arthur remembers. After Zeke’s passing, Arthur took Kevin to meet the owner of the Stanton-Davis homestead, John “Whit” Davis, who died at age 91 in 2016.

Arthur was surprised one day in 2005 to get a call from Whit inviting Liverant Antiques to appraise the contents of the house. “I thought, are you kidding me? My father would have paid $5,000 just to go through the house,” he says. Arthur and Kevin arrived on the appointed day and were told there was nothing of value on the house’s second floor, an assessment that proved largely correct. They then asked to see the attic.

“It was a classic kind of old Yankee attic, an accumulation of three centuries’ worth of mostly used-up furniture,” says Kevin, picking up the story where Arthur leaves off. “After adjusting to the lighting, I started looking around. There, buried under boxes of old canning jars and poking out from underneath a moth-eaten muskrat fur coat was the crest of a Queen Anne chair.” Sweeping the coat aside, the dealers found a circa 1740 maple armchair with bold turnings and its original leather upholstery. Now in a private collection, the chair is included in the Rhode Island Furniture Archive. Remarkably, the database developed by Patricia Kane and administered by Yale University Art Gallery contains nearly 100 pieces associated with the Liverants. “It was a King Tut’s tomb moment. The chair had probably been there for 150 years or more, tucked up under the south eaves of the house, surviving even during the hurricane of 1938,” Kevin marvels.

Great objects may not be hidden in old houses the way they were in Zeke’s time, but the life of an antiques dealer is in some ways little changed. “I’m still the one who goes out and chases the stuff. I put 45,000 miles a year on my Toyota Sienna. Even when I’m driving I’m on the phone. I have a wide web and our name is out there, but I’m still calling around all the time. My schedule is different every week,” Arthur says.

Kevin adds, “Nathan and Zeke laid the groundwork. Arthur has steadily built the network and strengthened the reputation of Liverant Antiques. Being in the same location all this time, people know where we are. We still get a lot of house calls and are able to bring fresh pieces to market. Hard work and dedication to reputation creates momentum. The hardest part for me is keeping up with Arthur. That hasn’t changed in 22 years.”

.jpg)

.jpg)

2.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)