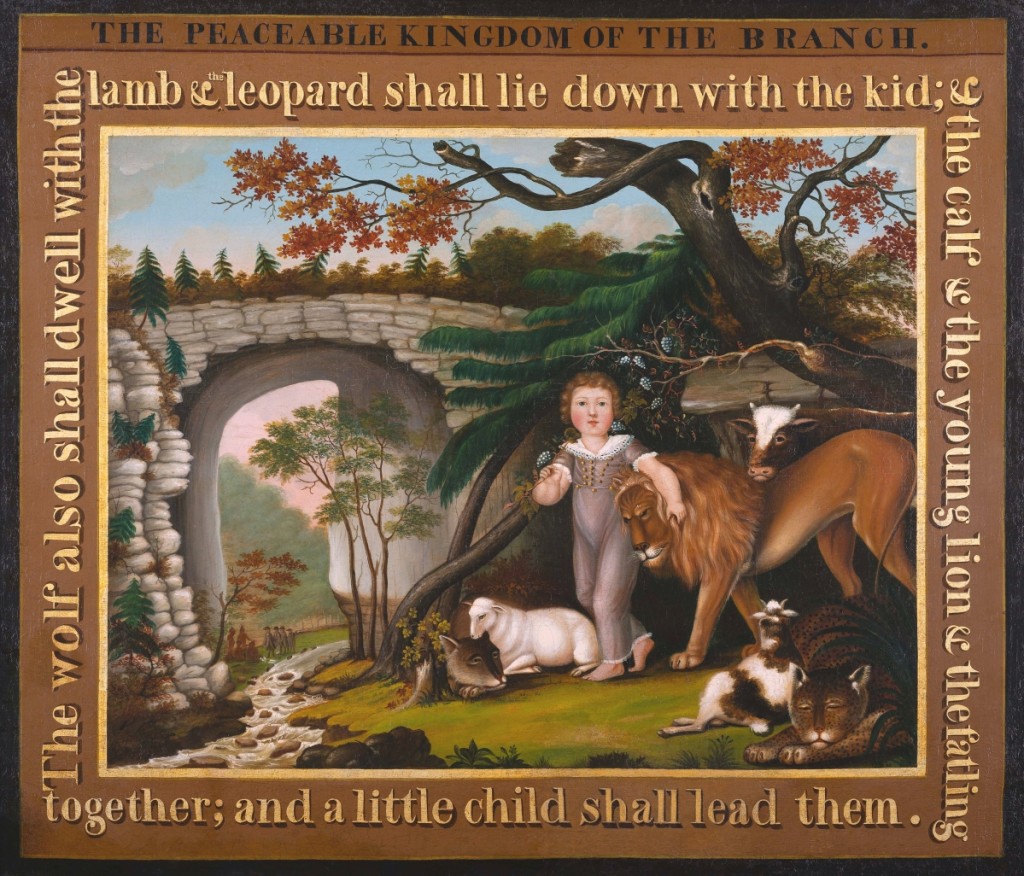

“Peaceable Kingdom,” Bucks County, Penn., 1832-34 Oil on canvas. Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Collection, gift of David Rockefeller.

By Laura Beach

WILLIAMSBURG, VA. – To what do we owe our enduring fascination with the Quaker folk painter Edward Hicks (1780-1849)? Is it the charm of the winsome creatures who congregate on his crowded canvases? The unexpected depth of meaning embedded in the painter’s amiable compositions? Is it received wisdom, a reflexively communal response to an artist whose work regularly surpasses the million-dollar mark at auction?

Laura Pass Barry, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation’s Juli Grainger curator of paintings, drawings and sculpture, has given decades of thought to the subject. Her findings are distilled in “The Art of Edward Hicks,” on view at the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum at Colonial Williamsburg through 2022. The exhibition presents a Hicks collection of incomparable depth, begun by the museum’s namesake founder Abby Aldrich Rockefeller in the early decades of the Twentieth Century and enlarged over time. This is the first time in roughly 20 years that nearly every Hicks piece in the collection is on view at once.

“I received my undergraduate degree from the College of Wooster in Ohio where I wrote a thesis on the iconography of Hicks’ ‘Peaceable Kingdom’ paintings,” Barry said recently by phone. “When Carolyn J. Weekley, now curator emerita, began work on the book and exhibition ‘The Kingdoms of Edward Hicks,’ which traveled from Williamsburg to Philadelphia, Denver and San Francisco between 1999 and 2001, she asked me to join her. It was one of those rare moments when everything came together. I spent five years working on that project, which makes this exhibit very personal and exciting for me.”

“Portrait of Edward Hicks” by Thomas Hicks (1823-1890), Newton, Penn., 1838-41. Oil on canvas. Museum purchase, 1967.

Born in Langhorne, Penn., Hicks began his artistic career as an apprentice to a Bucks County coach and sign painter. His faith informed every aspect of his life. A devout member of the Society of Friends and a practicing Quaker minister conscious of his faith’s general disdain for portrait painting, Hicks used his artistic talent to craft biblically-inspired messages, uplifting historical views and landscapes praising the hand of the divine. Hicks’ ministry sometimes took him far from Pennsylvania. An 1819-20 trip to upstate New York and lower Canada inspired the 1825-26 painted fireboard “Falls of Niagara,” probably presented to Philadelphia physician Joseph Parrish (1779-1840) in appreciation for free medical services. Roughly 130 paintings on canvas, panel and paper by Hicks, who died in Newtown, Penn., in 1849, survive.

Hicks’ messages of hope and peace have long resonated with collectors. Curator Holger Cahill (1887-1960) and dealer Edith Halpert (1900-1970) are generally credited with making Hicks an art-market star. The collaborators included a “Peaceable Kingdom” by the artist in their inaugural exhibition at the American Folk Art Gallery in New York in 1931. Abby Aldrich Rockefeller acquired two Hicks paintings in the present display from Halpert within the following two years.

In a 1985 oral history housed at the Archives of American Art, Philadelphia dealer Robert Carlen (1906-1990) likewise credits Cahill’s vision and Halpert’s panache for making Hicks America’s best-known folk artist. Carlen, who claimed to have bought and sold 30 Hicks paintings, mounted an exhibition of the artist’s work in the 1940s. As he told his interviewer, “I chased all over the country trying to locate the pictures…There are an awful lot of Hicks paintings in Bucks County because that’s where the artist lived.” Carlen lent two Hicks works to the Diplomatic Reception Rooms at the US Department of State, where they were on extended display.

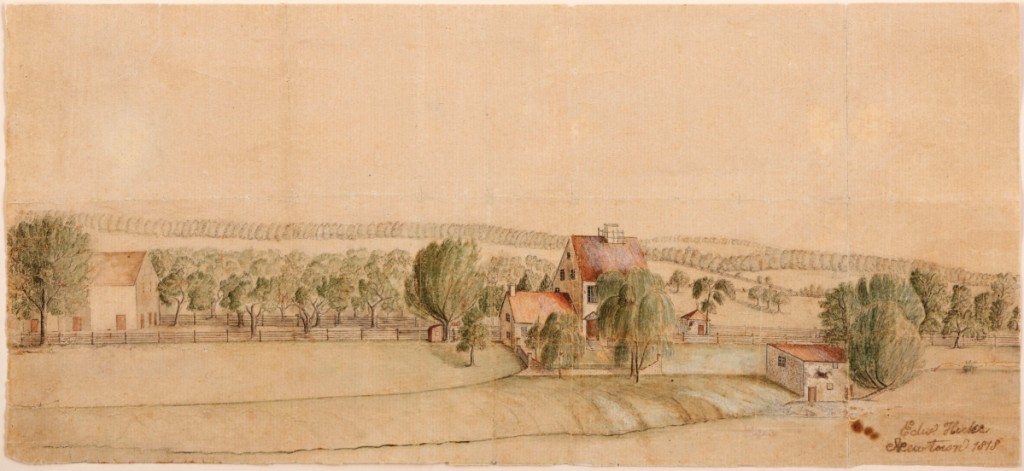

Painted in 1849, “Leedom Farm” is Hicks’s last and best painting, according to organizers “a summation of its predecessors, combining the artist’s remarkable skill, his love of family and friends, and his innate Quaker values for order, simplicity and man’s good works on earth.” “Leedom Farm,” Bucks County, Penn., 1849. Oil on canvas. Museum purchase, 1957.

“The Art of Edward Hicks” proceeds in a linear fashion around the circumference of one large space, addressing the artist’s early career as a sign painter, his landscape and history painting, and his “Peaceable Kingdoms.” The room’s soft, earthy palette emphasizes the artist’s connection with the land of his rural community. “It’s a very classic installation, with a gallery feel. We’re conscious of the museum’s varied audience and have worked hard to provide a mix of useful information of interest to newcomers and experts alike,” the curator says.

Hicks is best known for more than 60 “Peaceable Kingdoms,” paintings deriving from the biblical prophecy of Isaiah 11:6-9. Contemporary collectors comparing one “Kingdom” to another often focus on the quantity, variety, ferocity or docility of the animals in these lion-and-lamb pleas for peaceful coexistence. For Barry, the compositions, which evolved from print sources but over time became more personal to the artist, are laden with symbols, many of them Biblical in origin. They reflect the artist’s deep preoccupation with the 1827 rift between Hicksite Quakers, a more agrarian and generally poorer group wedded to ideals of personal modesty, and Orthodox Quakers, their more worldly, urban, affluent counterparts.

In a “Peaceable Kingdom” of 1826-28, Hicks included in the background a scene drawn from a popular engraving depicting the Quaker leader William Penn, shown in peaceful negotiation with local Leni-Lenape Indians. In a post-split “Kingdom” of 1832-34, the artist replaced the grapevine associated with Orthodox Quakerism with sheaves of wheat and ears of corn, representing the Hicksite belief in salvation achieved through the “light within.”

“Peaceable Kingdom of the Branch,” Bucks County, Penn., 1822-25. Oil on canvas. Museum purchase, 1967.

“The ‘Peaceable Kingdoms’ became personal reflections of contemporary events within the Society of Friends, specifically the schism of 1827 which divided the church into two factions. The ‘Peaceable Kingdoms’ created during and after the split are the most dramatic. You sense anguish in the faces of these animals which mirror the intense feelings of Quaker members. The artist uses the canvas and brush to work through his anxiety over this religious controversy,” Barry says.

The depth of the Colonial Williamsburg collection allows for the presentation of exceptional rarities. The earliest work on view is a circa 1800-05 shop sign Hicks created for his neighbor Henry Vanhorn, a carpenter and joiner whose cradle-to-grave bona fides are communicated with graphic precision. Another is “James Cornell’s Prize Bull,” likewise a painting on panel and an unusual instance of the artist painting on commission.

Barry finds no work more compelling than “Leedom Farm,” an oil on canvas completed by Hicks the year he died. A rosy calm descends over the barnyard and adjacent farmhouse in this view Hicks completed for his stepbrother David Leedom. Members of the Leedom family, including Mary Twining Leedom, Hicks’s favorite foster sister, and her husband, Jesse, stand watching over a contented flock. The organizers write, “It is the summation of its predecessors, combining the artist’s remarkable skill, his love of family and friends, and his innate Quaker values for order, simplicity and man’s good works on earth. In short, this painting is a highly personal statement about the serenity Hicks so fervently desired for humanity.” Barry notes, “I believe Hicks had reconciled himself to the fact that the split in the church that mattered so deeply to him would not be repaired in his lifetime.”

“Penn’s Treaty with the Indians,” Bucks County, Penn., 1830-35. Oil on canvas. Museum purchase, 1958.

The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation has steadily expanded its collection, in 1957 acquiring an 1840-45 “Declaration of Independence” by Hicks that had belonged to collectors Jean and Howard Lipman and was retailed by Connecticut dealer Mary Allis. Also accessioned that year was a “Penn’s Treaty with The Indians” of 1830-35 that passed from the dealer-turned-curator Charles Montgomery to the Massachusetts collectors J. Stuart Halladay and Herrel George Thomas.

The museum’s most recent acquisition, in 2017, was a rare signed and dated watercolor on paper of 1818 that surfaced at New York’s Winter Show. “We feel it’s most likely a preparatory sketch for the kind of farmscapes Hicks later created for friends, neighbors and supporters. It’s fascinating because it’s one of a few surviving works on paper by Hicks, created at a time when he was receiving landscape commissions as a coach and sign painter, and his only finished drawing. It seems to show an untutored artist thinking about how to put a composition on paper,” the curator says.

“The Art of Edward Hicks” is one of several new offerings at the Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg, which recently unveiled the results of a completed, multiyear expansion project designed to improve visitors’ access to the institution’s over 72,000-object collection by adding more exhibition space, improving amenities and rerouting foot traffic.

“Visitors now enter the museum through a well-marked, street-level entryway and a grand concourse that leads them to our iconic portrait of George Washington by Charles Willson Peale. At this point, guests are welcomed and ushered into the DeWitt Wallace Decorative Arts Museum and Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum collections and to the excitement of newly installed exhibitions,” Barry says.

Current displays include “American Folk Pottery: Art and Tradition,” arraying 50 ceramic objects made between 1790 and 2008; “Early American Faces,” illustrating the diversity of American society in an eclectic selection of portraits; and “British Masterworks: Ninety Years of Collecting at Colonial Williamsburg,” shining a light on a shifting institutional narrative through fine and decorative arts made between 1670 and 1840. Coming this fall are “Promoting America: Maps of the Colonies and the New Republic” and “Keeping Time,” both slated to open at the DeWitt Wallace Decorative Arts Museum.

Amidst this rich and varied program “The Art of Edward Hicks” stands out. As Barry explains, “When we were planning exhibits for the museum expansion, Hicks rose quickly to the top of our list. The idea of putting Hicks at the front and center of this celebration made sense. His messages of hope and peace are timeless.”

Located at 301 South Nassau Street in Williamsburg, the Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg are open daily from 9 am to 6 pm. For more information, www.colonialwilliamsburg.org or 855-296-6627.