By James Balestrieri

UNITED STATES – It is said that the Emperor Augustus ordered the goddess Iustitia – Justice – added to the Roman pantheon. Justice, in depictions then and ever since, is blind, holding aloft in one hand a set of scales and, in the other, a sword. Today, with the adjective social in front of justice, the first thing Justice would do is take that sword, slice off the blindfold and sweep the thumbs of systemic power from the scales, demanding not only to see, but to be seen, not as others would see her, but as she is.

This past spring, as museums – along with the rest of the world – shut their doors to try to keep COVID-19 at bay, video of the murder of George Floyd at the hands of the Minneapolis Police sent thousands into streets across the country and across the globe. Under the Black Lives Matter banner, the names of victims of police brutality became cadences of tragic verse and the demonstration. March and sign became the dominant visual artforms of 2020.

The sign is the sign of our times. Direct communication mirroring direct action, burgeoning into graffiti, the billboard, the mural, all these boil down to the concrete poetry of the portable, handmade sign. Font, color, medium: these are subservient to message, to slogan. The clever wordplay of text art reverts to plain, powerful text.

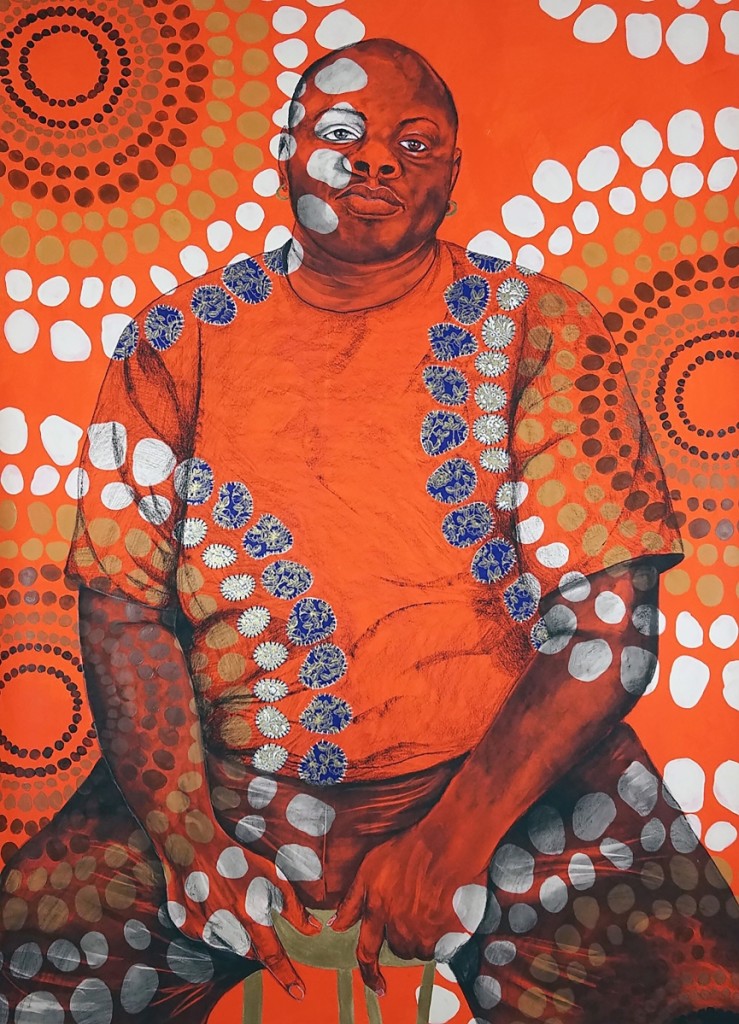

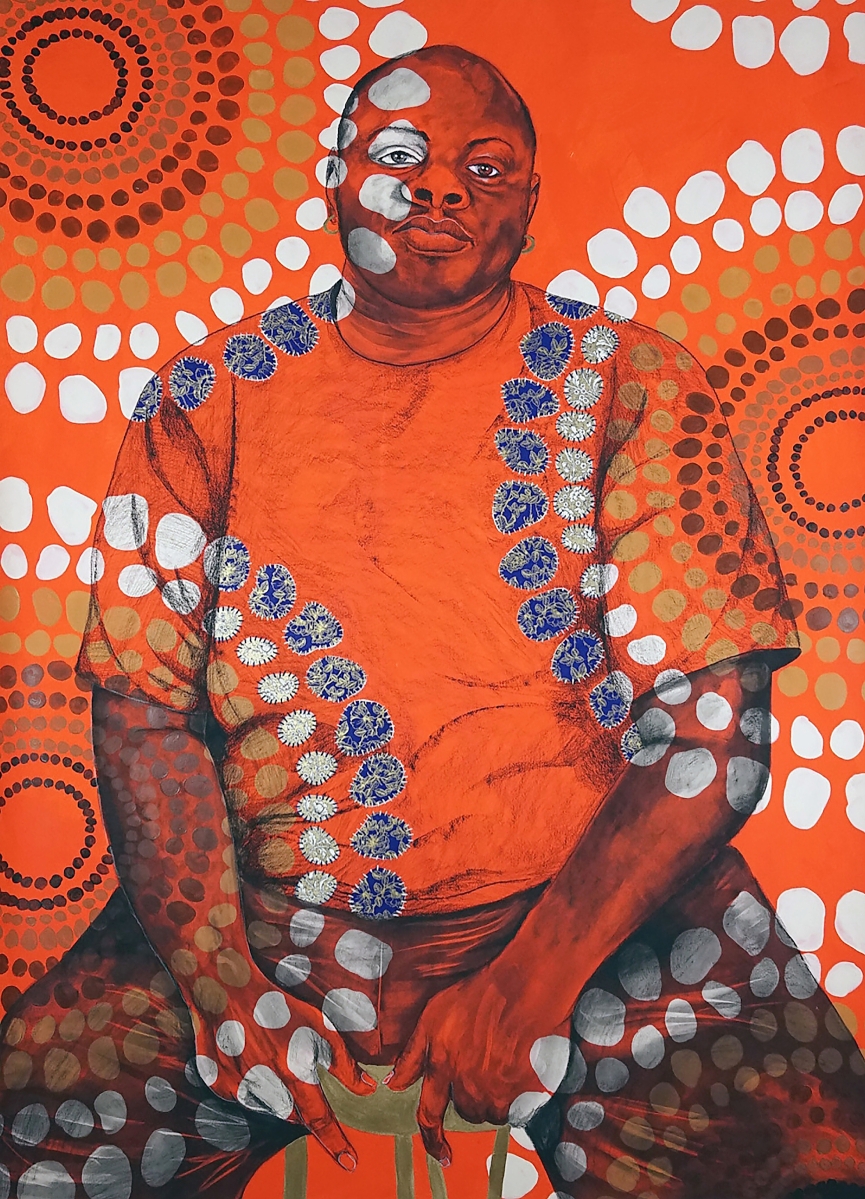

“Believing In Kings” by Delita Martin, 2018. Acrylic, charcoal, relief printing, decorative papers, hand-stitching and liquid gold leaf on paper, 71½ by 51 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Myrtis. Photo by Joshua Asante.

What will happen to these ephemeral signs of the times, this emotionally charged artless, unintentional art?

Sidelined by the virus, museums have remained relevant with innovative online programming, even as history – and art history – were being rewritten on the scrawled on cardboard signs being carried past their walls. Wisely, many museums, historical societies, and other institutions are asking protestors to donate their signs so that at least some of the expressions of 2020’s energy will be preserved and documented.

Social justice, however, has been no stranger to the missions of many museums since they were first conceived.

Since 1981, the National Museum of Women in the Arts has dedicated itself to redressing the historic underrepresentation of women, not only in museums and other institutions, but in the history of art overall. When I think of this imbalance, I think back to John Berger’s 1974 book Ways of Seeing, in particular the chapter on the nude in art and popular culture and its relationship to nakedness. Berger writes, “Men act and women appear. Men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at…”

“See, Speak, Hear, Yet the Bullets Continue / Ver, hablar, escuchar, mientras tanto las balas continúan,” by Román Villarreal (b 1950, American), 1998. Alabaster, 13¼ by 27 by 9½ inches. National Museum of Mexican Art Permanent Collection. A gift to the world on behalf of Román and María Villarreal. Photo credit Michael Tropea.

Now consider a woman considering a woman in her art.

Set Rania Matar’s 2019 photograph “Rayven, Miami Beach, Florida,” alongside Mervyn O’Gorman’s 1913 autochrome “Christina in Red,” or set it beside any Winslow Homer watercolor of women by the seashore. Christina is clearly “acting,” playing the pale, pre-Raphaelite beauty by the sea for her father, the photographer. Winslow Homer’s windswept women by the sea are either working fisherfolk, young swimmers showing their bare legs – this scandalized the press and public – or women in Victorian dress who seem ill at ease. All these are women who are being gazed at, watched, constructed, assessed. But something in the simple fact of a woman artist depicting a woman closes the gap between “acting” and “appearing.” Rayven seems to inhabit the moment, freed from questions surrounding race and skin color. The exposed areas of her skin suggest neither the classical nude nor the deeper exposure that accompanies nakedness. Rayven just is.

Mary Ellen Mark’s eerie monochrome, “Laurie in the Bathtub, Ward 81, Oregon State Hospital, Salem, Oregon, 1976” recalls David Lynch’s “Eraserhead.” But imagine the scene in two dimensions, grasp the idea of the disembodied head floating above a panel of bubbles – the head, like the mind, perhaps, alienated from the body – and think of a woman photographing this madwoman in the attic, taking a portrait of the hysteric – who seems rather calm – and all of the Victorian pseudo-medical notions of female hysteria, and the quack remedies for it, resurface. Now imagine this image captured by a man: the effect is instantly charged with sensuality.

Opened in 1987, the National Museum of Mexican Art in Chicago has championed artists of Mexican ancestry on both sides of the border, recognizing the artificiality of lines on maps and seeing no need for walls. Yet whether we are speaking of the actual border between the United States and Mexico, or the very real barriers between the barrios and a better life in American cities, the idea of walls, both as tangible obstacles and as media on which artists can document tragedy and express anger and hope – I am speaking here of the great mural tradition in Mexican art – is never far away.

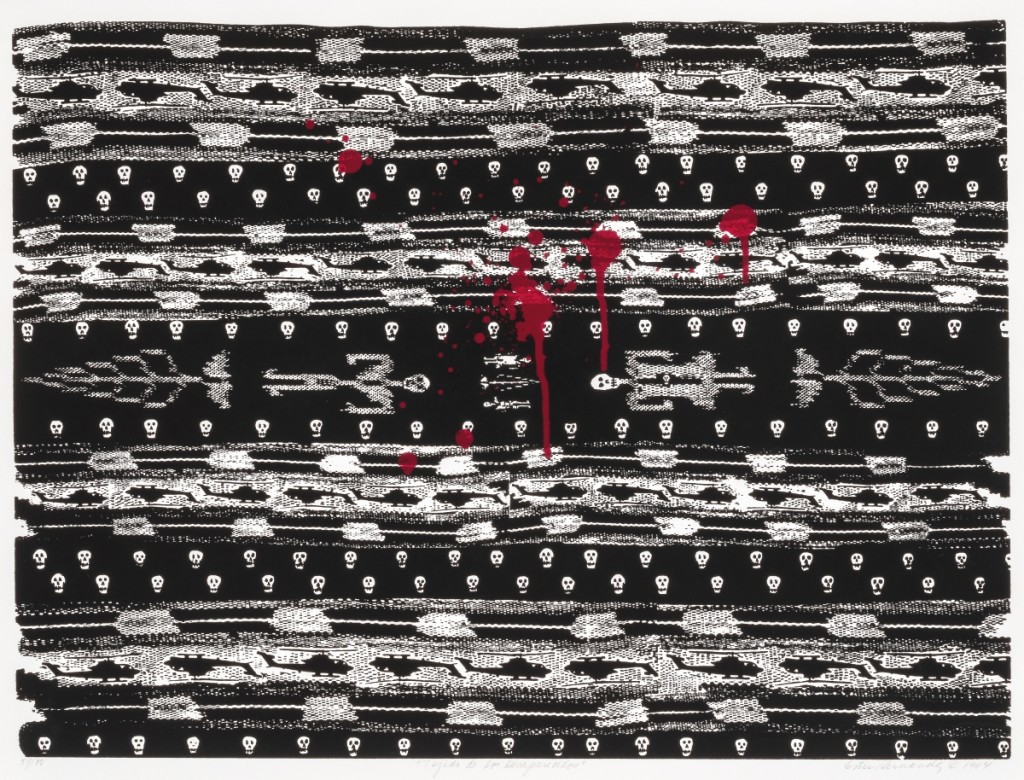

California native Ester Hernández’s “Tejido de los desaparecidos (Weaving of the Disappeared)” remembers those who vanished during the civil war in Guatemala in the 1980s. This repurposed shawl, an indigenous textile form, places the skulls and skeletons of the dead in black bands set off against bands of barbed wire and helicopters. Blood spattered on the fabric drips across the bands, linking killers to those killed, while two trees, growing out of the earth where the dead are buried, suggest the possibility of hope and reconciliation.

Marcos Raya and fellow Chicago artist Román Villarreal concern themselves with violence at the hands of power in disparate, yet somehow equally surreal ways. Raya’s large acrylic, “The Legacy of Manifest Destiny/El legado del Destino Manifiesto,” recalls Rivera and Orozco but seems to be a kaleidoscope of revolutions repressed and betrayed. Whether it is the Klan on the march north of the border or corruption and violence to the south, money and violence are always on the march and must always be countered by other marches for justice and peace. Villarreal’s alabaster sculpture, “See, Speak, Hear, Yet the Bullets Continue/Ver, hablar, escuchar, mientras tanto las balas continúan” feels like a fragment from a ruined temple where the dead, in skull masks, rise to keep up the good fight with and on behalf of the living. Crouched beside a wall, the figures in this tableau embody the cycle of violence in the world and the undying spirits who rise to meet it.

“Tejido de los desaparecidos (Weaving of the Disappeared),” by Ester Hernández (b 1944, Dinuba, Calif.). Serigraph, 51/100, 17 by 22 inches (paper size). National Museum of Mexican Art Permanent Collection. Photo credit Michael Tropea.

In Rocío Caballero’s “Broken Dreams/Los sueños rotos,” the artist traps a bride between two red crosses and hems her veil – a net, really – with cut out children, some of whom have fallen away. With nods to Kahlo and Dali, Caballero’s painting is an implicit critique of the church and of the strictures of traditional life for Latin women. The glorious sunset she paints also signals the end of a dream of independence.

The National Museum of African American History and Culture opened in 2016 to tell yet another side of the story of the United States, once again attempting to balance the scales, telling stories that have waited, some for a very long time, to be told in full.

Marching with signs in the United States seems, after a cursory investigation, to take off after the Civil War with the Women’s Suffrage Movement. Soon after, the labor and civil rights movements followed. The political sign coincides with an explosion in visual culture. Rapid advances in lithography and photography give rise to illustrated periodicals and advertising – including billboards – and the political cartoon. Excerpts from a speech could appear in a news article, but a slogan on a placard, illustrated in a newspaper or magazine, turned readers into instant viewers.

-759x1024.jpg)

“The Legacy of Manifest Destiny / El legado del Destino Manifiesto” by Marcos Raya (b 1948, Irapuato, Guanajuato), 1995. Acrylic on canvas/acrílico sobre tela, 96 by 72 inches. National Museum of Mexican Art Permanent Collection, 2001.28. Gift of Nora Ribadeniera Carranza in honor of her family. Photo credit Kathleen Culbert-Aguilar.

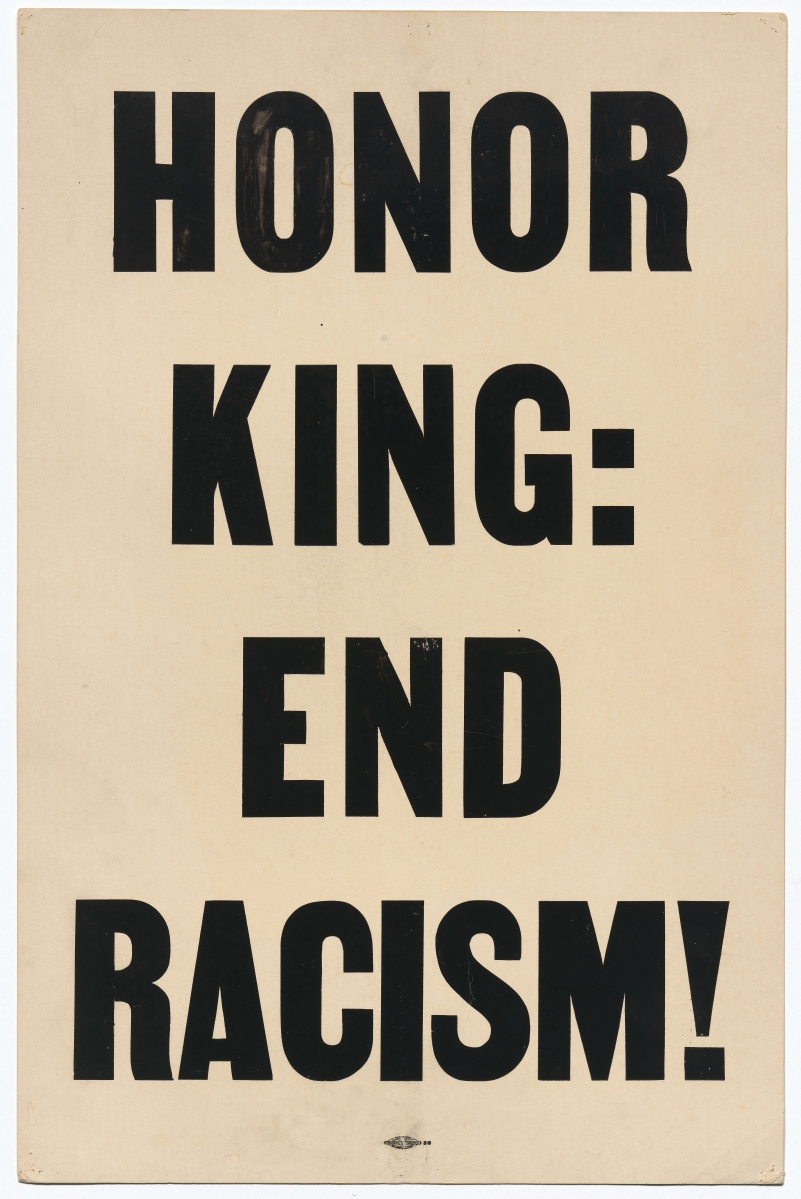

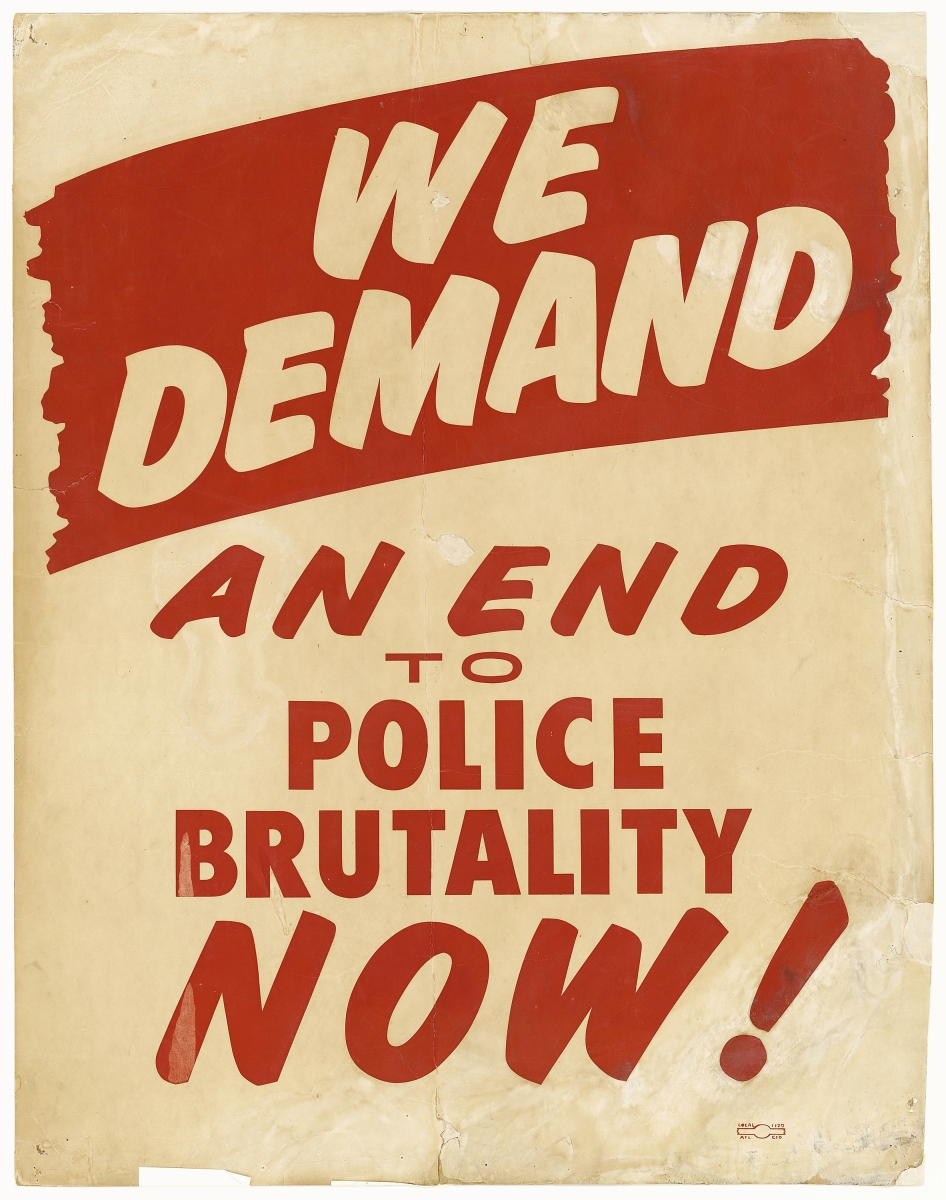

Consider the two signs reproduced here. “We Demand an end to Police Brutality,” was carried in the 1963 March on Washington that ended with Martin Luther King’s “I Have A Dream” speech while “Honor King: End Racism” was carried through the streets of Memphis after Dr King’s assassination. Both signs are printed, mass-produced. Photographs from the respective marches show hundreds of people, side by side, carrying these signs. This is the sign of a mature movement, one that wants to project strength and unity through the repetition of words and imagery. Indeed, in order to suggest immediacy and spontaneity, the words “We Demand” on the 1963 sign appear to be cut out from and revealed by a ragged slash of red paint. The font and size of the letters on this sign vary, imitating a hand in a hurry and voice shouting “Now!” Conversely, “Honor King,” is stark, in a strong, single font, as black and white as the tragic message it conveys.

Now look at the two photographs from the 2020 protests outside the White House. Not one is printed. All are homemade.

As a group, they scream diversity within the unity of a cause. They are individual messages, even personal. What, after all, does “I Miss My Dad” mean until and unless we connect this with George Floyd’s young daughter? “When will you stop painting over the words of the people?” speaks to power and erasure and could very well be a mantra for our age as the news cycle shrinks to minutes and seconds. Red handprints convey their message without words. They are taped over, covered over, expression palimpsested onto expression. And they are international: “Japan Stands With You” is scrawled beneath a red shirt, blue jeans, and bandanna – the hachimaki of courage. Beside them: a message of solidarity and a twitter hashtag. There is some coalescence and solidarity in the George Floyd murals in Minnesota, and those painted on boarded up shops around the country in the wake of violence. But for the most part, these images indicate fluidity, rapidity, diversity, individuality.

“Rayven,” by Rania Matar, Miami Beach, Fla., from the series “SHE,” 2019. Archival pigment print, 37 by 44 inches. National Museum of Women in the Arts. Museum Purchase, funds provided by Sunny Scully Alsup and Elva Ferrari-Graham. ©Rania Matar.

Movements move at the speed of light. One of the new roles of museums is to keep up, to separate the tangled strands of the present, the competing ideologies, even those that arise within protests and counter-protests, within movements and moments and create an interpretative prism of perspectives. The first step is to preserve the artifacts of the present, a present that, in our digital, social media age, becomes the past with the click of the keyboard. Institutions dedicated to social justice begin with the simple gesture of displacing the dominant white maleness of the aesthetic gaze. Some are selling major works in order to purchase works by artists of color, by women, by LGBTQ artists.

To balance the scales, the scales have to be taken from the eyes of the holders and beholders of power, of the state of things as they are, whether we are speaking of politics or art. But the clamor of voices requires another order of attention when individuals in underrepresented groups insist on defining their own identities, claiming difference and, and as, heritage.

There will be no re-blindfolding the eyes of Social Justice in any museum. That’s the only sure sign of the future.

-1024x768.jpg)

2-768x1024.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

2.jpg)