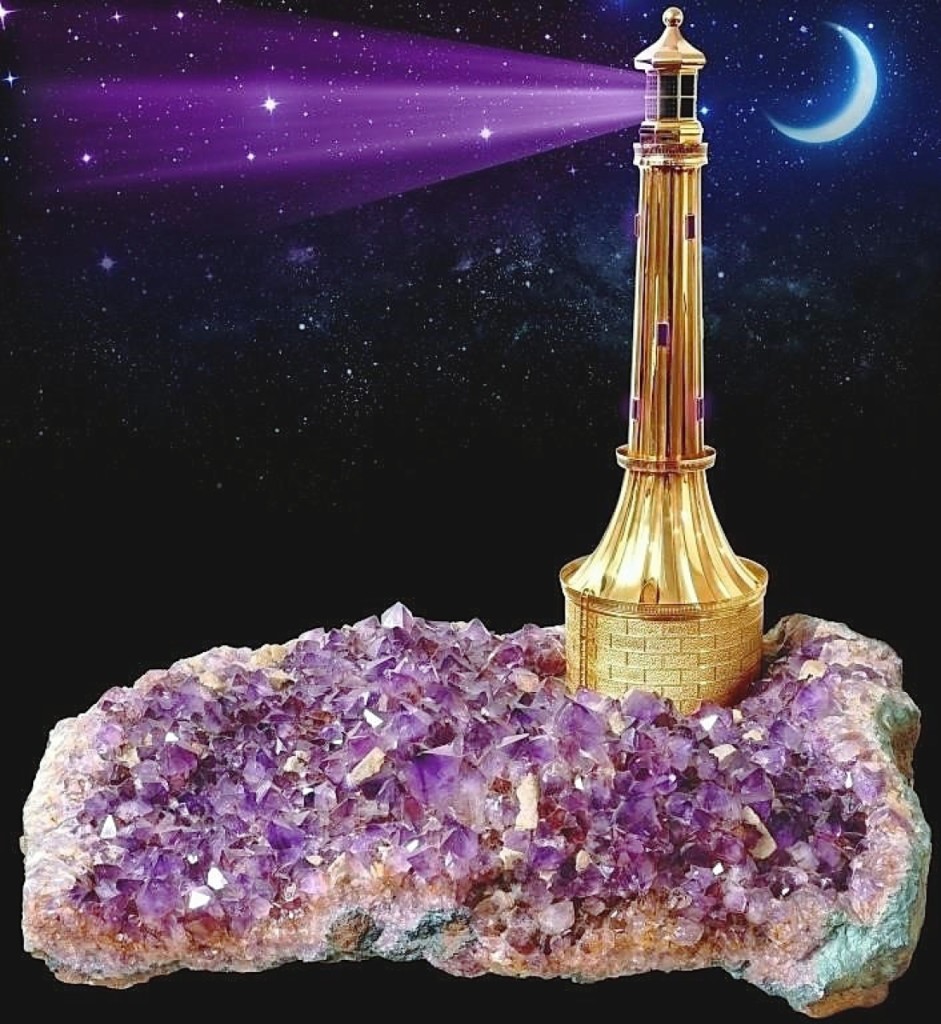

The star of the sale was a solid 18K gold cigarette lighter made by Dunhill in the detailed form of a lighthouse. It was 18 inches tall and mounted on a 110-pound section of an amethyst geode with large crystals. When made in 1985, it was priced at $56,000 and was listed in the Guinness Book of Records as the world’s most expensive cigarette lighter. It may still hold that distinction, having sold for $110,000.

Review and Onsite Photos by Rick Russack, Additional Photos Courtesy Jones & Horan

GOFFSTOWN, N.H. – George and Patty Jones of Jones & Horan conduct two major cataloged sales of watches and related objects annually, as well as online-only sales every two weeks. So, they sell a lot of watches. They’ve been in the business for more than 35 years and their business model may be unique. It makes bidding as simple as possible for buyers and gives their consignors advantages almost unheard of in this day and age. There are no reserves – everything sells. The buyer pays only what he or she has bid. There are no buyer’s premiums, domestic shipping is free and done in-house (with minor exceptions), insurance is free, and there is no sales tax in New Hampshire. On an item selling for $10,000, the savings to a successful bidder could add up to around $2,500 to $3,000. In addition to simplifying the bidding process, the absence of a buyers’ premium means that the consignor will receive the full hammer price of the object, less the agreed-upon auction house commission. Using the $10,000 example, if an auction house charges a 25 percent premium, the buyer will pay $12,500 but the consignor would receive only $10,000, less the commission. George Jones is vociferous in his belief that this is the fairest way of doing business for both the buyer and seller.

Bidding is also made simpler by the fact that all descriptions of a watch follow a standardized template. That means that all relevant technical details are presented in the same order for each listing. A standardized definition of condition is clearly spelled out in the catalog, and all descriptions are guaranteed with a full ten-day refund policy. Condition reports are detailed and include the condition of the packaging, when appropriate. In most cases, there will be a minimum of six photos used online for each item, and when helpful, as many as 20 photos may be used. If an interested buyer asks for an additional photo, that photo is added to those already online. YouTube videos show many of the watches working.

This Waltham one-minute repeater with split-seconds chronograph and a 60-minute register was one of the three known examples and it sold for $100,000, well over the estimate. Only three total American pocket watches have reached the six-figure mark at auction, Jones & Horan has now sold two of them.

On November 1, the firm’s sale grossed $1.27 million. It included jewelry, men’s and ladies’ wristwatches, pocket watches, military timepieces and chronometers, clocks, related ephemera and more. In this instance, the “and more” category included the top-selling object of the day. It was a solid 18K gold cigarette lighter made by Dunhill in the detailed form of a lighthouse, 18 inches tall and mounted on a 110-pound section of an amethyst geode with large crystals. The gold base of the lighthouse was cut to accommodate the amethyst crystals. The gold alone, weighing 50.88 troy ounces, was worth $71,000 at the day’s market price. When lighted, the top emitted a purplish tinted light to reflect the amethyst base. The lighter had been made in 1985 as part of Dunhill’s Christmas collection that year and was priced at $56,000. For decades it was listed as the world’s most expensive cigarette lighter in the Guinness Book of Records, and perhaps with this sale, it regained that position. It had most recently been owned by Henry Dorman, chief executive officer of the National Enquirer, one of the most widely circulated newspapers in the United States.

The sale began with 22 lots of ladies’ jewelry. Bringing $6,800, the highest priced piece in the selection, was a 1.85-carat diamond and 18K gold engagement ring. Made by Boucheron of Paris, the diamond had a clarity rating of VS-2. It’s always interesting to ask an auctioneer if an item in a sale had been a real “discovery.” When asked that question, George Jones selected this ring. “It came in a plastic baggie with a bunch of other jewelry, most of which had little value,” he recalled. “When I saw this ring in the bag, it really caught my eye and I wondered is it real? When I looked closely, I saw the Boucheron mark and knew that we had saved a really fine ring.” Selling for $5,200, the second highest price of the ladies’ jewelry part of the sale, was a 21-inch-long “monster” 14K gold Figaro chain with a lobster claw clasp, weighing 86.2dwt.

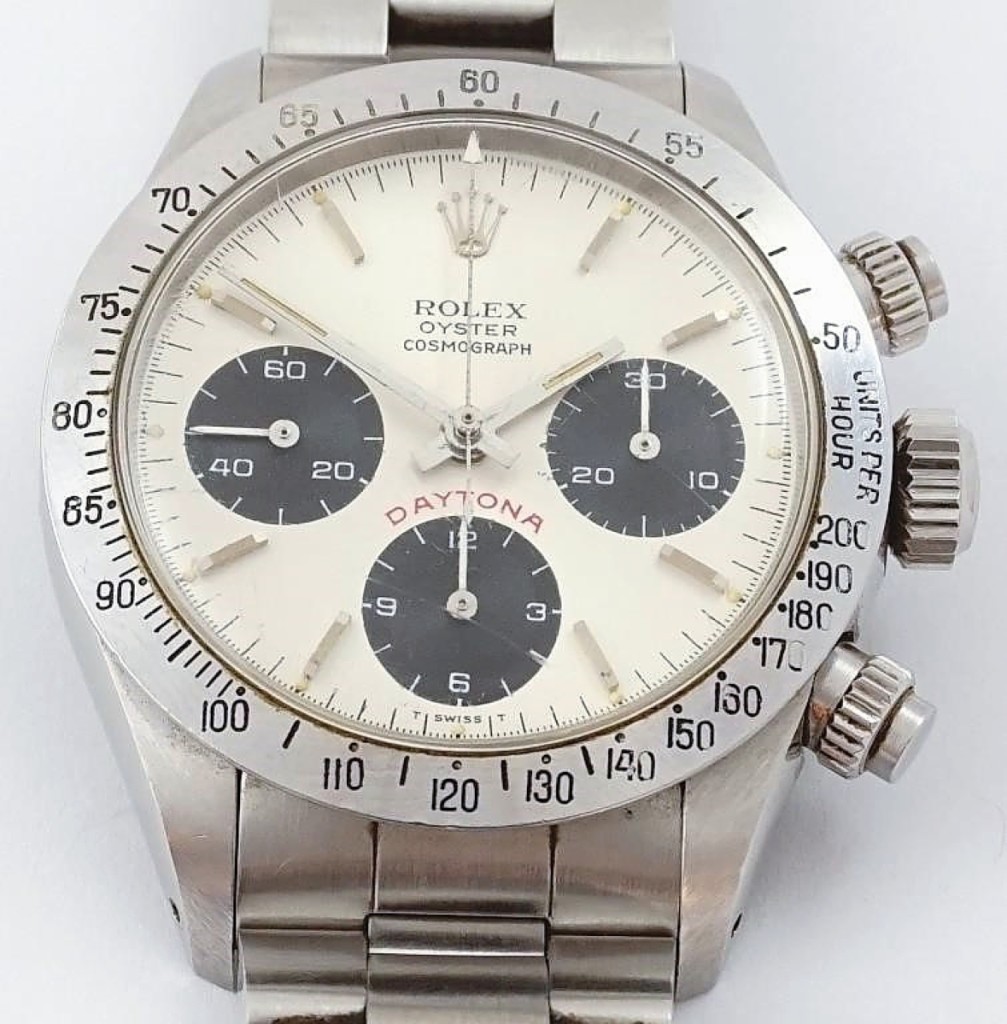

At $75,000, the third highest priced item in the sale was a circa 1979 Rolex Oyster Cosmograph Daytona wristwatch with its original inner and outer boxes as well as the manuals, original punch papers and matching hang tag with serial number. It had been kept in a safety deposit box since the late 1980s.

Having noted the above, it was clearly watches that buyers wanted, and one paid $100,000 for a Waltham, one-minute repeater with split-seconds chronograph and a 60-minute register in a massive, original 18K gold hunter case. It was cataloged as “an important and exceedingly rare watch,” with the cataloging continuing, “We are aware of the existence of only two examples of the Waltham one-minute repeater with split-seconds chronograph. The single other example we have encountered was sold by Sothebys in 2004, and was formerly a part of the Rockford Time Museum collection and it was in a ‘reconstructed case.’ This example is notable for its superb condition throughout including its very heavy original gold hunting case made by prestigious New York casemaker Jeannot & Shiebler. It has been owned by our consignor since the mid-1970s and is offered here to the marketplace for the first time in more than 40 years.”

Its selling price was well over the $60,000 estimate. The day after the sale, Diana Kelly, the firm’s chief operating officer and auctioneer, said that the sale of this watch marked only the third time that an American pocket had sold at auction for $100,000 or more “and we also sold one of the other two,” she said. “That one brought more than $300,000. It was a Howard, Davis & Dennison pocket watch and we sold it last summer.”

Buyers also responded well to a circa 1979 Rolex Oyster Cosmograph Daytona wristwatch with its original inner and outer boxes as well as the manuals, original punch papers and matching hang tag with serial number. In the mid-1980s, the original owner had the black dial changed for the current silver dial by a Rolex authorized dealer and kept this watch in a safety deposit box since the late 1980s. It sold for $75,000. Bringing $22,000 was a Patek Philippe, Genève, five-minute repeater with split-seconds chronograph and 60-minute register, retailed by Jaques & Marcus of New York. It was in a 53mm, heavy 18K rose gold original hunter case. It had a dark blue enamel monogram inlay of initials to the front and the date 1888.

Tyler St Gelais is the firm’s wristwatch specialist and truly loves his job. He was trained as a goldsmith at the North Bennet School in Boston and said that his favorite item in the sale was a Longines Flyback Chronograph that sold for $9,600. “I really like it because it’s a very complicated mechanism that does many different things. Those are my favorite kind of watches.”

The catalog described it as “an unusual watch with split-seconds chronograph in combination with a five-minute repeating function rather than the more typically seen minute repeating function, and the presence of a 60-minute register rather than the more typically seen 30-minute register.” Interestingly, when the watch was most recently serviced by Patek Philippe, the consignor was advised “to make sure the watch is fully wound before engaging the chronograph functions and also that due to the age of the piece it should not be carried and run daily.”

The sale included a number of early and unusual watches. Perhaps the most unusual was one that was designed for the adventure lover. It was made by Cartier, and, in case the watch stopped while its owner was hiking or far from home, it included a sundial and compass. In an 18K gold case, a small post could be lifted to create a real sundial, although of a delicate construction. The catalog provided some history: “Cartier workmanship from a bygone era when Cartier’s biggest clients were royals and when decadence was on a different scale. Very few sundial compass watches were produced by Cartier; a notable example that belonged to the late Duke of Windsor was sold in 2010 by Sotheby’s for £63,650.” That was then and this is now – without the noteworthy provenance, this example brought $8,400.

Erotica has always existed, and watches were no exception. Made by Dubois & Co, a signed 18K gold quarter-hour repeater with Jacquemart automaton included a shuttered erotic scene. Although the catalog did not provide a date, it was likely from the early Nineteenth Century and it sold for $7,000. A 30-second YouTube video on the catalog page showed the watch working. It was not the only piece of erotica on offer.

An unusual gold watch made by Cartier and apparently intended for nature lovers or hikers, this watch included a sundial to tell time in case the watch stopped and a compass to help its owner find his or her way. It sold for $8,400, and the catalog entry provides more information on these watches.

The day after the sale, George Jones said, “We were really pleased. The lighthouse was a one-of-a-kind piece and brought what it should have. It will be quite an addition to someone’s home. We’ve now sold two of the three most expensive American pocket watches with the Waltham repeater. That’s a nice record to have. Our consignors were happy and so were our buyers. The $1.27 million total reflects the work the whole team put into the sale. And I’m always glad when we can help a consignor realize the fair price of an item they knew nothing about, as we did with the diamond ring.”

When Diana Kelly was asked which item surprised her, she quickly said, “It was the last item in the sale, an early fusee watch made in London, with a single hand that we think dated to the late Eighteenth Century but it may have been earlier. It brought $6,000 against our estimate of $1,000.”

And when Fred Hansen, one of the watch experts who catalogs for the company, was asked about unexpected surprises, he commented on the early Hamilton pocket watch with a low serial number that sold for $8,400, twice the estimate. Hamilton records indicate that it was originally sold January 13, 1894. “It came from a good collection of Hamiltons that we’ve been selling. It was an early example.” The other positive comment he made concerned the fact that each sale brings new customers.

Prices given are hammer as the auction house charges no buyer’s premium.

For information, 800-622-8120 or www.jones-horan.com.