Installation views, “Poetry and Patronage: The Laubespine-Villeroy Library Rediscovered,” October 16 through May 16, 2021, Thaw Gallery. —Graham S. Haber photo

By Rick Russack,

NEW YORK CITY – From now through May 16, the Morgan Library & Museum in New York City presents “Poetry and Patronage: The Laubespine-Villeroy Library Rediscovered.” The exhibition brings together, for the first time in almost 450 years, some of the most spectacular bindings from the library of Claude III de Laubespine, one of the great but little-known bibliophiles of the French Renaissance.

During the Renaissance, manuscript and printed books and their fine bindings were symbols of the wealthy and cultured. Claude III de Laubespine (1545-1570) met all the criteria. He was a member of an influential family, many of whom held high offices during the reigns of French kings Henry II and Charles IX. His father, Claude II, played an important role in both domestic and foreign policy and was a chief advisor to Catherine de Medici, mother of Charles IX. Claude II, a secretary of state, married into a rich and cultivated family, thus acquiring several homes. Other members of his family were also holders of important posts.

Claude III de Laubespine grew up at the royal court and, with just a three-year difference in age, was close to the future king Charles IX. At the age of 16, following in his father’s footsteps, he also became a secretary of state, a position about equivalent to a cabinet secretary in the United States government, and rose high enough in the royal entourage of Charles IX to be entrusted with missions abroad. As his father had done, he also married a wealthy heiress, Marie Clutin, and his wife’s wealth allowed him to live a lavish lifestyle. He was one of Charles IX’s most trusted advisors and clearly a member of “the jet set” of his day. Among the extravagant dinner services and long dining tables where the aristocracy came to gather in his many homes, Laubespine had shelves to fill, and he did so with books.

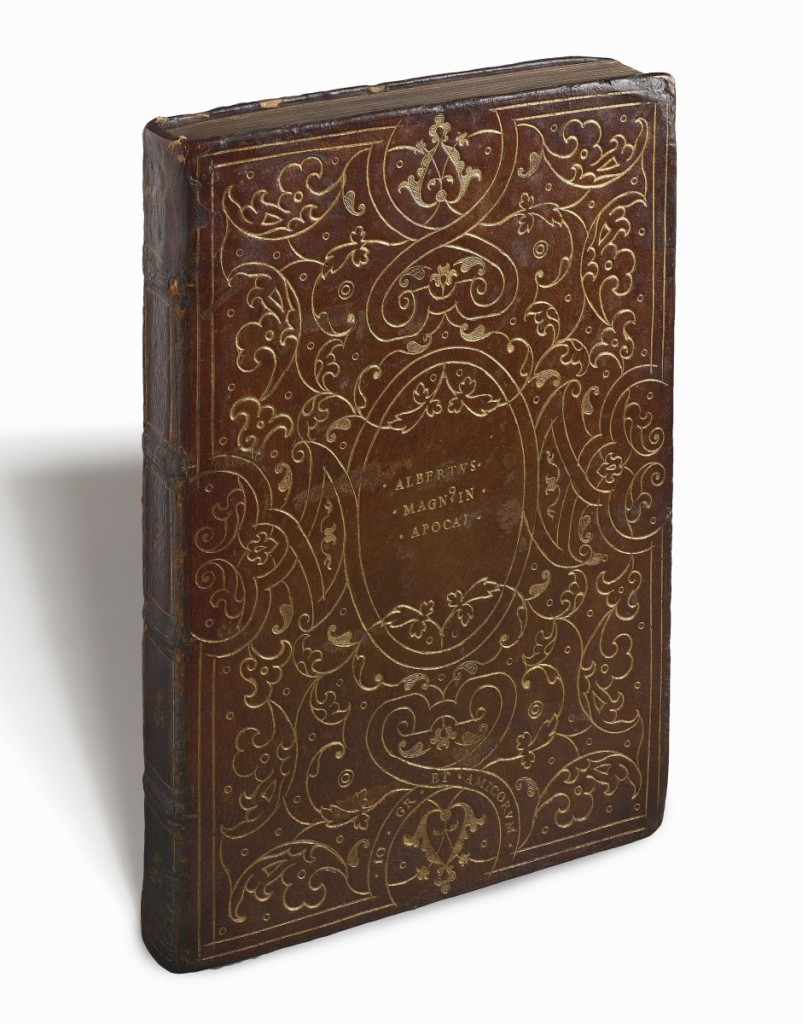

Saint Albertus Magnus (1193?-1280) Postillatio in Apocalypsim (Commentary on the Book of Revelation), Basel: Jacob von Pfortzheim, 1506. The Morgan Library & Museum, purchased in 1912. —Graham S. Haber photo

Claude III de Laubespine was passionate about poetry and praise. Several of the outstanding poets of the era, such as Pierre de Ronsard and Philippe Desportes, seeking patronage from Claude III’s family, composed elegant tributes in verse praising him; his father, Claude II; his sister, Madeleine, and her husband, Nicolas de Villeroy.

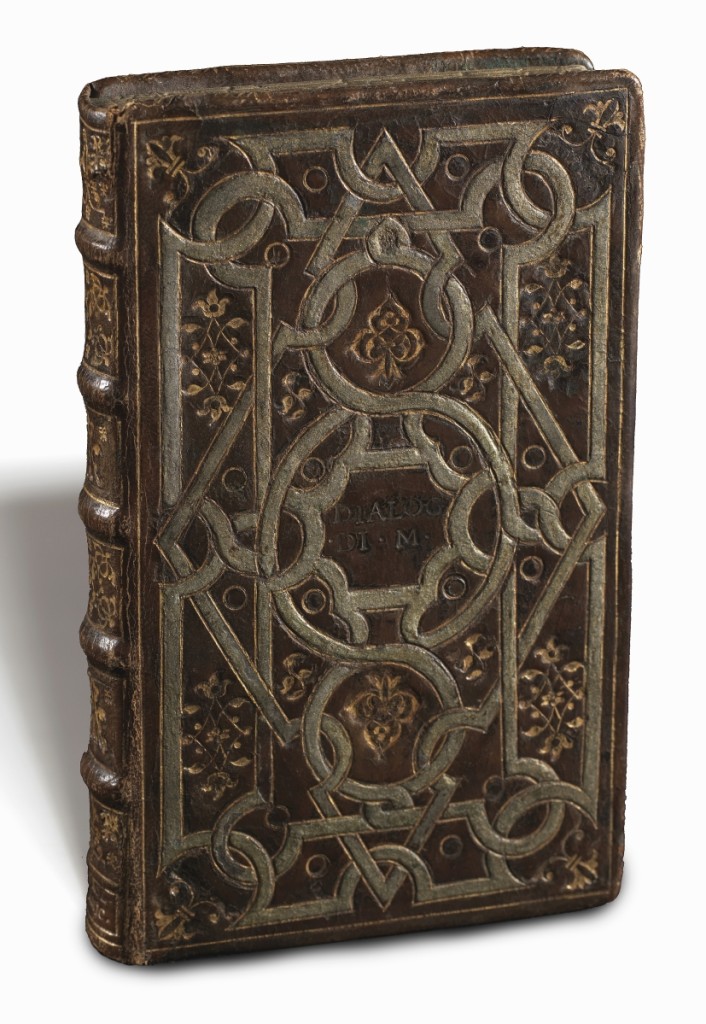

Claude III de Laubespine built an extensive library, of which poetry was only one facet, and he patronized the leading bookbinders of the Renaissance, whose workshops were creating the finest bindings in France. Some of those shops had also worked for Jean Grolier (1479-1565), the famed Treasurer-General of France whose library has gained international renown. Laubespine’s great credibility in the bibliosphere, although rivaling that of Grolier, has not been recognized until now.

A simple explanation for the disparity is that Grolier’s books were clearly identified with his name and crest, but Laubespine’s were not. Identifying his books and tracing their fate was difficult and not finally resolved until this exhibition.

In 1993, Isabelle de Conihout, guest curator for this exhibition, became intrigued and began her quest to establish the scope and fate of the dispersed collection as she located as many books as possible. She invested years of research and travel to numerous libraries in Europe and around the United States to first understand the scope of his collection, research the material, and then gather it for this exhibit. She has contributed a major essay to the catalog that accompanies the exhibition.

Circle of Jean Decourt (circa 1530-after 1585), “Portrait of Madeleine de Laubespine, dame de Villeroy,” Sixteenth Century, oil on panel. Collection of William Kopelman.

She determined that Claude III de Laubespine and his sister, Madeleine were close in age and apparently fond of one another. Madeleine was also a talented poet and patron of literature and author of at least 59 sonnets as well as some erotic poems. She also married well, choosing Nicolas de Neufville, sieur de Villeroy, who would also become a secretary of state, serving four successive kings of France until his death in 1617. Claude III had no children, leaving his estate to be divided between his sister Madeleine and a younger brother. The division of that estate was contorted but it eventually became clear to de Conihout that Claude III’s library passed to Madelaine and then to her husband. Following his death, and after the sale of the family home that contained the library in 1640, dispersal followed and most of the books went to leading Parisian book collectors.

In a 2015 interview, when de Conihout joined Christie’s as a specialist in Parisian books, she was asked about the most memorable moment of her career. Her reply was “my discovery of the Renaissance library of Claude de Laubespine.” She described a moment at the Bibliothèque nationale de France where she found two circa 1560 beautifully bound books on architecture, each with a distinctive shelf mark in a Sixteenth Century hand, but no further identification as to whom they had belonged. In her words, “I went on searching and finally found in the BnF 40 volumes in extraordinary bindings, all bearing the same shelf-marks, which I called the ‘cotes brunes.’ I continued my search in other Parisian libraries where I found about 40 additional volumes, still revealing nothing about their original owner. In British and American libraries, and in a few private collections, I eventually had discovered more, about 120 altogether, but still with no clue as to original ownership.

“It was in a literary manuscript that I finally picked up the trail. The finely bound manuscript, with a double C repeated, was believed to have belonged to King Charles IX. Upon opening it I was surprised to find my ‘cote brune’ written on the fly-leaf. The volume was an early luxurious calligraphic edition of the love poems of the French court poet Philippe Desportes, and it contained a final sonnet from about the year 1570. In it Desportes mourns his ‘wise, happy, and perfect’ friend, Claude de Laubespine. That was the clue I needed and I was finally able to solve the mystery.” This exhibit, and the accompanying catalog, are the result of her search.

![Francesco Colonna (d 1527) Hypnerotomachia Poliphili (The Strife of Love in a Dream by the Lover of Polia), Venice: Aldus Manutius [for Leonardus Crassus], December, 1499. The Morgan Library & Museum, purchased with the Irwin collection, —Graham S. Haber photo](https://www.antiquesandthearts.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/strife_of_love-1024x740.jpg)

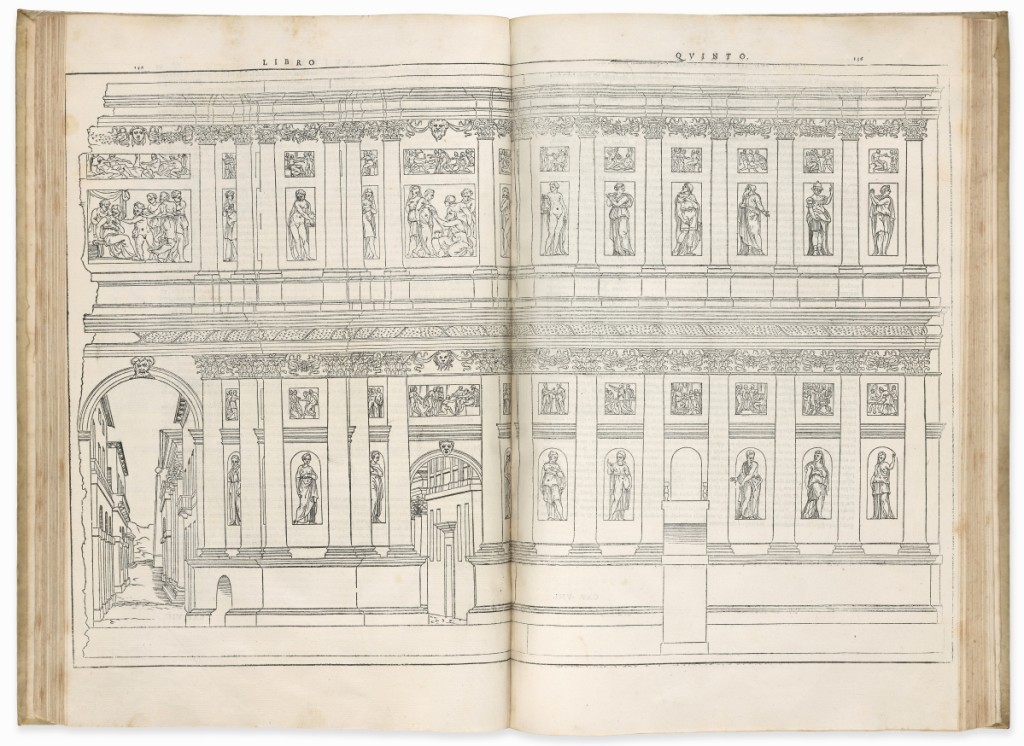

Francesco Colonna (d 1527) Hypnerotomachia Poliphili (The Strife of Love in a Dream by the Lover of Polia), Venice: Aldus Manutius [for Leonardus Crassus], December, 1499. The Morgan Library & Museum, purchased with the Irwin collection, —Graham S. Haber photo

The organizing curator, John Bidwell, Astor curator of printed books and bindings at the Morgan, said, “Isabelle’s research in the history of the Laubespine-Villeroy library has greatly enhanced our understanding of book collecting during the French Renaissance. The fine bindings were works of art in their own right, reflecting the knowledge, wealth and taste of the collectors who commissioned them.” The Morgan’s director, Colin B. Bailey concurred, “This is an exhibition that revisits the central role of bindings in our collection and, at the same time, one of the most splendid libraries of the French Renaissance. The exhibition takes a close look at the art of connoisseurship through the detailed task of reuniting an exquisite set of bindings that have been separated for over four centuries. Isabelle de Conihout’s scholarship allows us to see that fine bindings were works of art in their own right, reflecting the knowledge, wealth and taste of the connoisseurs who commissioned them and the artisans who created them.”

The exhibition includes a copy of Jacopo Vignola’s Regola delli cinque ordini d’architettura of 1564 as well as Hypnerotomachia Poliphili (1499) by Francesco Colonna, the latter which curators called one of the greatest illustrated books of all time.

“They’re all lovely books, but in my opinion, the most spectacular are bound by Atelier au Vase,” said Bidwell. “Remember that very few of these bindings can be attributed to a person. Sometimes you know about a royal binder, there are documents that will give you that name, but otherwise you’re dealing with eponymous workshops. In the exhibit, you’re seeing the work of different workshops of that time.”

Both of the above titles were produced by Atelier au Vase and are of a large size.

Vitruvius Pollio (active First Century BCE) I dieci libri dell’architettura (On the Art of Building in Ten Books), translated with a commentary by Daniele Barbaro, Venice: Francesco Marcolini, 1556. The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Paul Mellon, 1979.

—Janny Chiu photo

“The size gave the binder a greater canvas to work with,” Bidwell said. “One of the outstanding features of what we call primitive or empty fanfare binding is that you get this exquisite ornamental design with these perfectly spaced compartments – everything just falls into place.”

The ornamentation does nothing to mute the subtle glow and quality feel of the Moroccan leather.

“In Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, this is brought one step further by treating that leather with powdered gold, an extra luxurious touch, which is rare. You can tell Laubespine the collector regarded this one book as special.”

Not much is known of Atelier au Vase, Bidwell said, with only recent research revealing the bookbinder’s existence.

“There are generations of bookbinding scholars who have worked on the French Renaissance, which is a high point in the whole history of binding,” Bidwell said. “Like many fields of art history, there is a constant attribution and reattribution of books. The Atelier au Vase is an example of these recent attributions.”

Sperone Speroni (1500-1588) Dialoghi (Dialogues) Venice: Sons of Aldus Manutius, 1546. Barbier-Mueller Foundation for the Study of Italian Renaissance Poetry (University of Geneva) / e-codices – Virtual Manuscript Library of Switzerland.

The Morgan Library & Museum began as the private library of financier Pierpont Morgan (1837-1913), one of the preeminent collectors and cultural benefactors in the United States. As early as 1890 Morgan had begun to assemble his collections, which included more than books. Mr Morgan’s library, as it was known in his lifetime, was built between 1902 and 1906 adjacent to his New York residence at Madison Avenue and 36th Street. The library was designed by Charles McKim of the firm of McKim, Mead and White and cost $1.2 million. It was made a public institution in 1924 by Morgan’s son John Pierpont Morgan Jr, in accordance with his father’s will.

Pierpont Morgan’s immense holdings ranged from Egyptian art to Renaissance paintings to Chinese porcelains. For his library, Morgan acquired illuminated, literary and historical manuscripts, early printed books and Old Master drawings and prints. To this core collection, he added the earliest evidence of writing as manifested in ancient seals, tablets, and papyrus fragments from Egypt and the Near East. Morgan also collected manuscripts and printed materials significant to American history. The institution has continued to acquire rare materials, but the bindings collection, which comprises about a thousand volumes, is outstanding. They also have three copies of the Gutenberg bible, one of which is complete.

For information, www.themorgan.org or 212-685-0008.