“Chase Rolling Mill” by Elsie Rowland Chase, circa 1895. Oil on Masonite board. Mattatuck Museum, gift of Fredericka Chase.

By Kristin Nord

HARTFORD, CONN. – Connecticut is in many ways a cultural mecca, with strong regional museums and a plethora of historical societies capturing various aspects of the state’s history and heritage. Yet in some ways this embarrassment of riches poses a logistical challenge. How might the state capitalize on this legacy, and make it perhaps less overwhelming to the public?

With the creation of the Connecticut Arts Trail 25 years ago, cultural tourism became both a strategy for economic development and a boon for the curious, who have snapped up $25 individual passports in increasing numbers. Each passport has granted annual entry to 22 museums and historic sites.

And what a rich history there is to share – dating back most prominently to the efforts of Daniel Wadsworth (1771-1848) who is credited with making Hartford in the Nineteenth Century a major arts center and a model of enlightened society.

In many ways the Wadsworth Atheneum, which opened on July 31, 1844, and would become highly regarded for its quality and depth, was Wadsworth’s crowning achievement.

The Wadsworth Atheneum opened its doors, the art historian Elizabeth Mankin Kornhauser notes, “when the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and the Brooklyn Museum – to cite three great public collections of American paintings that share relatively early histories – were just being established.”

Wadsworth had made it his mission to celebrate America’s cultural heritage in the museum he established, and his patronage of the arts set the tone for an appreciation of culture that continues to this day. In future generations, other institutions of stature would sprout and become significant museums in their own right. Taken together they hold a half-million paintings and objects, scattered throughout institutions in cities and towns within the state’s 5,543-square-mile radius.

“When the founding museums first gathered, over two decades ago, I’m not sure that anyone imagined that this trail would not only continue to thrive but grow in reach and reputation, across the country,” Carey Weber, volunteer president of the Connecticut Art Trail and executive director of the Fairfield University Art Museum, said. But the idea took off, and now, in this commemorative year, she added, the time seemed right to bring together works from member museums. Tom Loughman, the Wadsworth’s chief executive officer, agreed to host the exhibition, and James Prosek, an Easton, Conn., native, and a renowned artist, writer and naturalist, was tapped to curate.

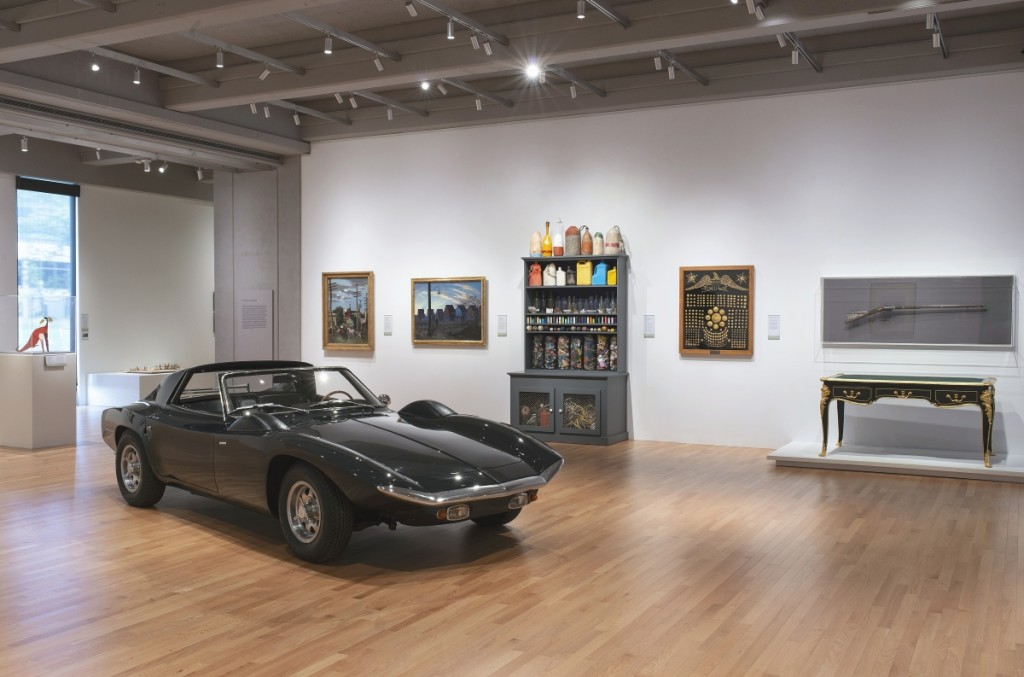

The end result is a visual buffet that will be running through February 7 (and overlaps Prosek’s solo exhibition, “Art, Artifact, Artifice,” which is on at the Yale Art Gallery through February 27.

“Aloft,” a study for New London Post Office mural by Thomas LaFarge, 1935-37. Charcoal on paper. Lyman Allyn Art Museum, Gift of Mrs Thomas LaFarge.

The 90 or so paintings, objects and artifacts in “Made in Connecticut” take us on an eclectic journey, from fossils and a hand-carved indigenous wooden bowl to prints and paintings, sculpture and industrial products. Prosek’s own close observations of nature have led to wide-ranging creative expression, and he credits both his father’s passion for nature and his own exposure to such wonders as could be discovered in the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History. It was there where he remembers being entranced by its taxidermy dioramas; a later encounter with Winslow Homer’s watercolors would similarly take his breath away. Prosek published his first book by the time he was 19. Today, in his 40s, the Yale Art Gallery’s Artist-in-Residence has a wide body of acclaimed work and has exhibited in solo and group shows in Connecticut and throughout the country. Prosek said he is eager to give his young son the same opportunities for study and enrichment as he received from his Brazilian immigrant father.

Thomas Cole’s famous oil painting, “View of Monte Video, the Seat of Daniel Wadsworth, Esq,” hints at Wadsworth’s erudition and embrace of the aesthetic theories of the day. The picturesque seemed to suit Connecticut’s landscape, and Wadsworth counted not only Cole, but Frederic Church and Frederick Law Olmsted as friends. Hartford life at that time could also be experienced in domestic trappings such as the carved ivory lamp screen, one of two commissioned for Armsmear, Samuel Colt’s elegant estate.

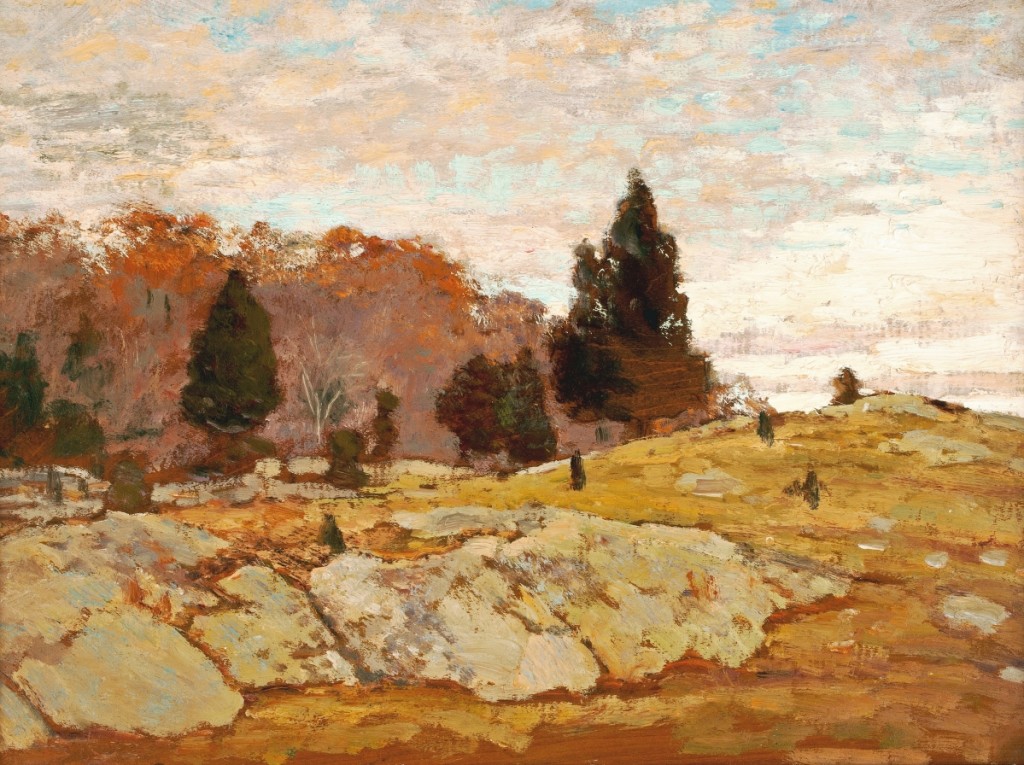

By the end of the Nineteenth Century, the American Impressionism movement would flourish, as artists fled New York City during the summer months to paint en plein air at Miss Florence Griswold’s farm in Old Lyme. Others gravitated to Cos Cob and Branchville. Paintings by Childe Hassam, J. Alden Weir and Frank Vincent DuMond demonstrate why the Connecticut landscape was such a potent lure.

“Connecticut Cedars” by Allen Butler Talcott, 1887-1908. Oil on board. New Britain Museum of American Art, John Butler Talcott Fund.

At the same time, Connecticut has an incredible industrial story to tell, with its cities brimming with factories by the mid-to-late-Nineteenth Century, and its manufacturers leading the world in the production of arms, brass, silver, tools, textiles, thread, hats and even typewriters. There is a prototype for the Colt Revolving Rifle that was commissioned in about 1832 by Samuel Colt, some 20 years before the founding of the Colt Patent Firearms Manufacturing Co., in Hartford. The curio case holds brass buttons from 1875, when Waterbury led the gilt button industry, with its patriotic configuration possibly bound for an industrial fair of some kind. On loan from the Mattatuck Museum in Waterbury is Charles Goodyear’s vulcanized rubber desk, a marvel, with its gilt, leather and cabriole legs, designed and crafted to promote the potential applications of rubber. It was displayed at The Great Exposition at London’s Crystal Palace in 1851.

Another technical marvel, “the Blick” portable typewriter, manufactured by the Blickensderfer Manufacturing Company in Stamford, was a stylish contender when the typewriter industry was booming.

Connecticut could claim its share of artists who were deeply involved in experimentation and innovation. Katherine Dreier, an artist and patron who lived in West Redding, would join forces with Marcel Duchamp and Man Ray to found the Societé Anonyme in 1920. The Societé would fuel exhibitions in Modern Art throughout the country.

More recently, Alexander Calder had his studio in Roxbury in the mid-1950s, and many of his massive works were fabricated in Waterbury and Watertown. Josef Albers, who chaired the Yale School of Art’s Department of Design from 1950 to 1958, was studying the interaction of solid colors placed next to each other in his signature series, “Homage to the Square.” Helen Frankenthaler, a leading abstract expressionist painter, lived in Stamford for many years and was instrumental in the founding of the Center for Contemporary Printmaking in Norwalk. As a place offering land with often spectacular views, affordable prices and easy proximity to New York, the allure was understandable.

“New Britain Seen From Newington” by John G. Matilus, 1942. Tempera on panel. New Britain Museum of American Art, gift of David Matulis.

Even during dark times there were opportunities for artists as the Public Works Art project, an initiative spawned by President Roosevelt’s New Deal, commissioned murals for public buildings like Thomas La Farge’s masterful depiction of sailors engaged in the whaling era, which still hangs in New London’s Post Office.

Not all of Connecticut’s engineers and tinkerers were successful, however. Among the quixotic ventures was the Fitch Phoenix, the sleek and stylish race car that John Cooper Fitch, hoped to bring to market. Sadly the 1966 prototype stayed just that.

Prosek has selected a number of contemporary works that address racism, gender equality and threats to the environment. He has chosen a work by Roger Tory Peterson, who invented the modern field guide. Peterson’s book played a large role in the conservation movement – and now, more than 80 years after the book’s publication, we can see in Prosek’s own distinctive work how he is furthering the conversation.

Mark Dion’s “Cabinet of New England Marine Debris,” colorful and charming at first glance, becomes a serious conceptual work when the visitor grasps that it is filled with detritus that is littering the New England shoreline. How far we seem to have come from the late 1800s becomes clear in contrast to Willard Metcalf’s cabinet, with its hundreds of bird eggs, moths, butterflies and nests, inspired by the artist’s visit to Claude Monet at Giverny. Metcalf continued to build his collection during his summer visits to Florence Griswold’s boardinghouse between 1905 and 1907 and it resides at the museum in Old Lyme to this day.

“View of Monte Video, the Seat of Daniel Wadsworth, Esq” by Thomas Cole, 1828. Oil on wood. Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, bequest of Daniel Wadsworth.

Childe Hassan and John Henry Twachtman, Alexander Calder, Anna Hyatt Huntington, Kay Sage and husband Yves Tanguy, Sally and Milton Avery, Arshile Gorky, Sol LeWitt and J. Alden Weir, as well as Prosek himself, make for heady company. But this show will no doubt convince visitors that they have barely scratched the surface of an epic, and still-unfolding, tale. When the state reemerges from this most trying of times, the art trail will be calling us to hit the road again.

Entrance to the Wadsworth and the “Made in Connecticut” exhibition are included with the passport, which can be purchased online at ctarttrail.org or at any member location. Timed tickets for limited capacity viewing are available at www.thewadsworth.org. Check the website for further information on safety protocols and requirements for admission. For updates about trail visits, see www.ctarttrail.org.