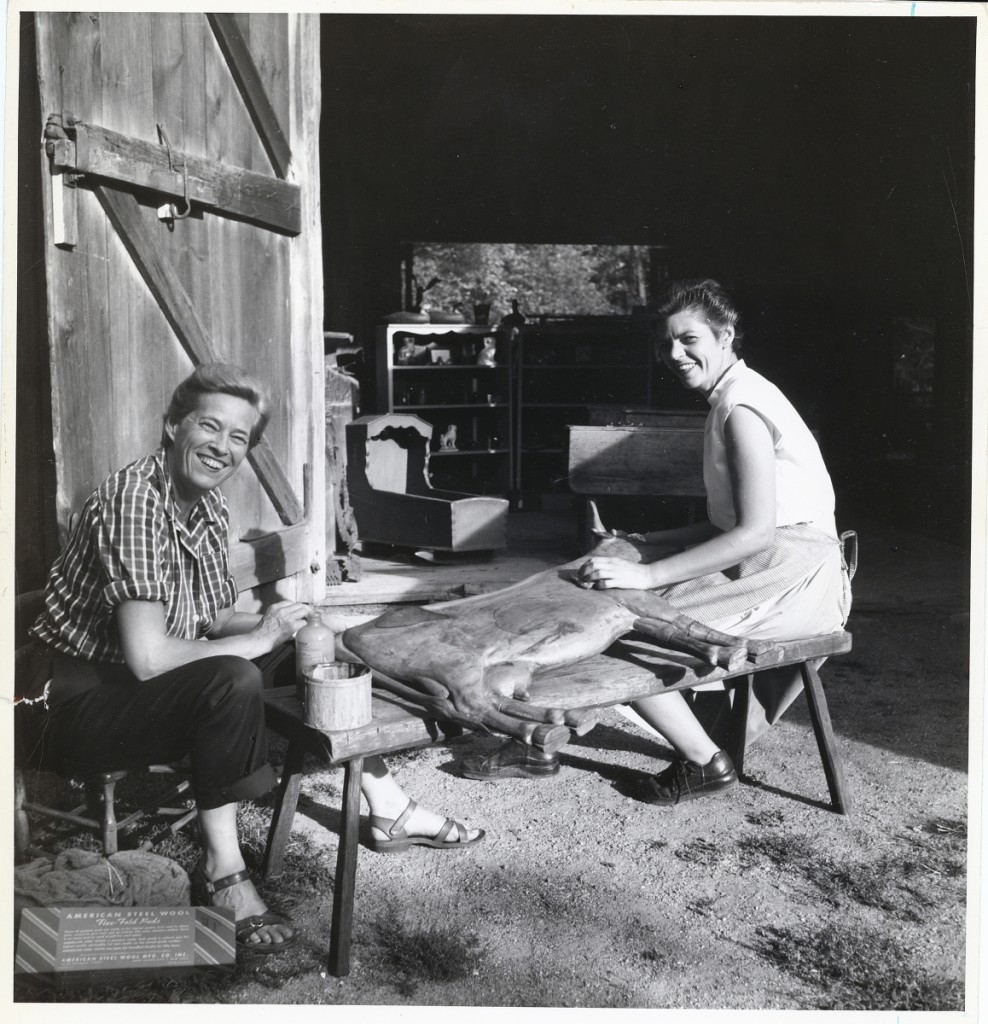

Cordelia Hamilton and Adele Earnest, two of the museum’s co-founders. Photo courtesy of the American Folk Art Museum.

By Greg Smith, Editor

NEW YORK CITY – When the American Folk Art Museum, then known as The Museum of Early American Folk Arts, adopted its charter in 1961, “it was really a gallery over a deli in a townhouse,” said Jason Busch, the museum’s director and chief executive officer. For what it lacked – and it lacked quite a bit: a permanent home, an endowment, even a collection – it made up for in its perseverance and vision, one that was, notably, a forebearer of the great push for diversity in art that institutions are frenetically scrambling to fill today.

The museum now spans two boroughs in New York City, its gleaming gallery in Lincoln Square pulsing with energy beamed over from its administrative offices, archives and library that reside in Long Island City, Queens.

The six decades since its inception have been an evolution for the institution, which adopted its current name in 2001.

With one foot in material of the past, its eye towards modern and contemporary folk art was near instantaneous, fearlessly led forward – even against the resistance of some of its patrons who wished to focus more narrowly on historic folk art – by curator Bert Hemphill Jr, an icon in the field whose stature is smoothly mentioned alongside Abby Aldrich Rockefeller and Jean Lipman. In 1964, Hemphill became the museum’s first full-time curator and a year later he launched its first solo exhibition championing the work of Tennessee sculptor William Edmondson.

Installation shot of the 1974 exhibition “Folk Art Underfoot.” Photo courtesy of the American Folk Art Museum.

There are words that regularly crop up in conversations about folk art that directly relate to the predicament many museums found themselves in when the pandemic jeopardized their existence this past March. Among them are “sidelined” and “survival.”

In the museum’s most recent exhibition, “American Perspectives,” a show curated by Stacy C. Hollander that closed its opening run just last month, Busch said the works “showcased all mediums and works by living or recently deceased artists who came to their subjects through survival and expression, just like Ammi Phillips or Sheldon Peck were creating as a way to survive financially.” Though their beauty may, on the surface, determine a more ideal landscape, behind the paint lay a showcase of strain that related to the undercurrent of pain and expression felt throughout the United States in the last four years as a tidal wave of social justice movements swept throughout the country. “The collection we had on view revealed that these were also challenges in the past, as they provided a resource for understanding, solace, hope and expression,” Busch said.

The exhibition opened in February 2020 and closed three weeks later as New York City became a veritable ghost town. The mirror of survival turned inward as the museum’s programming was sidelined.

When AFAM opened back up in August, among the first institutions in the city to do so, Busch and his staff – among 30-some professionals – as well as the board, emerged from the looking glass without vanity. None were laid off in the meantime and all had sat down, together but apart, to craft a strategic plan that would pull the museum through its next 60 years.

A work by William Edmondson featured in the 1965 exhibition of his work at The Museum of Early American Folk Arts. This was the first solo artist exhibition organized by Bert Hemphill Jr for the museum. Photo courtesy of the American Folk Art Museum.

“Our board of 21 trustees is so active and committed, and they want to help and roll up their sleeves,” Busch said. “Our staff is our greatest asset and our collection is our second greatest asset. If we’re not going to look at cutting staff, with the board’s great support, then we would look at exhibitions. We had to shave off a significant amount of budget towards exhibitions, but we did so with the idea that we were closed for five months.”

The museum’s downtime provided a chance for retrospection in each employee’s role, their processes and what changes wrought by the pandemic are worth bringing forward. Among the carryovers will be a significant digital push, including all 6,500 objects in the collection being made available online by 2026. A new website is in the works as e-publications and online exhibitions begin to come to the fore and digital programming takes a foothold.

Busch characterized the museum’s in-person and digital programming, a hybrid model, as its future. “People can participate throughout the world,” he said, “Our virtual programs attracted participants all over the globe, from the United States to Turkey to Pakistan to Japan, Argentina, Portugal and the United Kingdom. It has expanded our scholarship, the reach of what we’re doing with programs and collections. It’s made us an international resource for advocating folk art and self-taught art across time and place. We’re really embarking on a bright new chapter.”

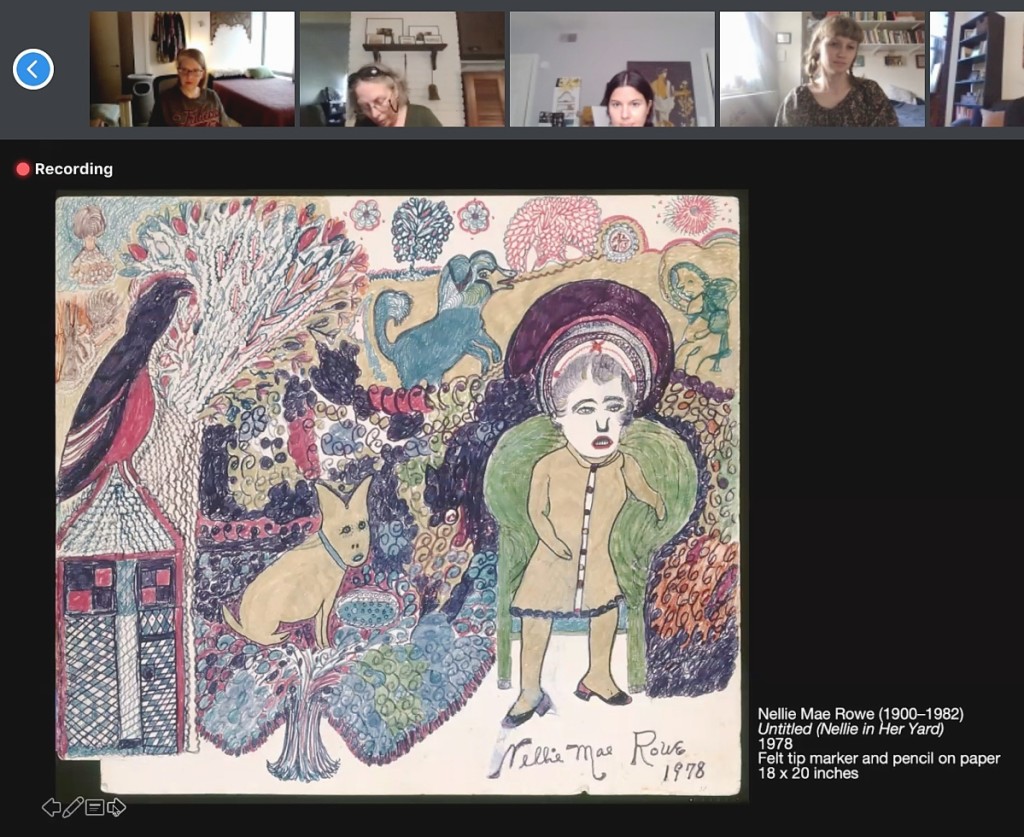

Curator of folk art Emelie Gevalt led viewers through a virtual tour of “Signature Styles: Friendship, Album, and Fundraising Quilts.”

That also involves the digitization of another chapter, 14 volumes of them, in Henry Darger’s “Realms of the Unreal,” a project made possible through a Save America’s Treasures grant from the National Park Service. With the largest public collection of Darger works, the museum plans to make an online portal that will broaden the reach of his art and writings.

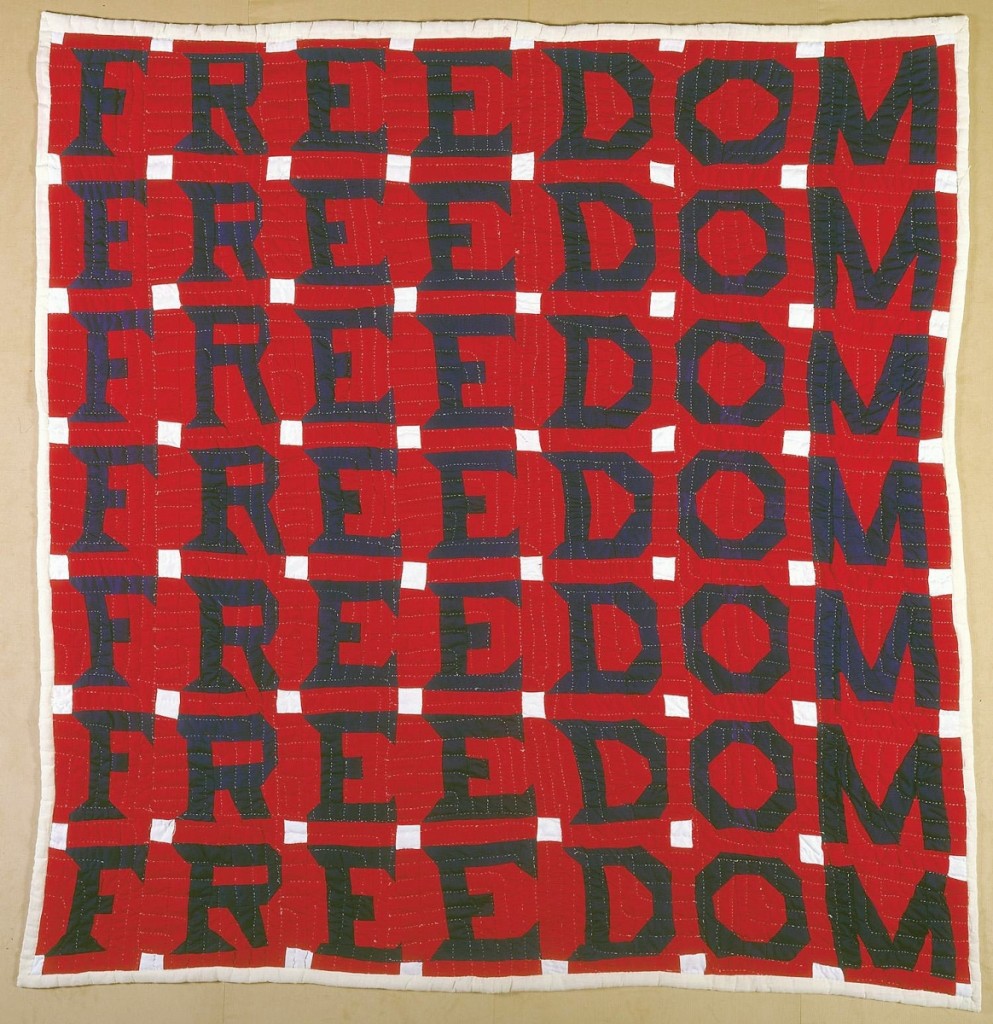

In a moment when the American public is increasingly looking towards an edit of American history that includes a broader point of view, AFAM’s collection of self-taught, folk and outsider artists who represent a more home-grown, non-academic and democratic vision of American ingenuity are increasingly apt for the bill. AFAM’s collections will travel outward in the years ahead into the galleries of museums across the nation as American art receives a revision in scope and priority. “From coast to coast and north to south, there will always be an AFAM exhibition on view in some part of the country,” Busch said. “American Perspectives: Stories from the American Folk Art Collection,” “Handstitched Worlds: The Cartography of Quilts” and “Wall Power! Spectacular Quilts from the American Folk Art Museum” will venture forth.

As New York City thaws in the months ahead, the exhibitions the museum has planned in their own galleries have much to offer. Recently opened is “Photo | Brut: Collection Bruno Decharme & Compagnie,” which has received celebratory marks since its January 24 opening. For those who prefer the icons of Americana, the museum will open “American Weathervanes: The Art of the Winds” in June. Opening in January 2022, will be “Multitudes,” a monumental showcase of folk and self-taught art that spans four centuries of creation and repositions the museum’s collection in terms of “multiplicity encapsulated by the production of the artists themselves…and the idea of ‘containing multitudes’ as a metaphor for the museum’s collection as a whole.”

Freedom Quilt by Jessie B. Telfair (1913-1986) Parrott, Georgia, 1983. Cotton with pencil, 74 by 68 inches. Collection American Folk Art Museum, New York; Gift of Judith Alexander in loving memory of her sister, Rebecca Alexander. Photo by Gavin Ashworth.

“It’s not a chronological show,” Busch said. “It looks past present and present past to identify themes. It will present not only icons, but also those that are undersung heroes that are being rediscovered.”

After the 2019 departure of its chief curator in Hollander, who had been at the museum for 34 years, new voices are emerging at AFAM that will forge its future. Among them Dr Valérie Rousseau, who came on in 2013, and Emelie Gevalt, hired in 2019.

“Our curators are constantly evaluating the collection,” Busch said. “They’re both relatively new to our museum, so they’re taking the time to identify strengths and gaps.”

As the museum launches a Gifts of Art campaign that asks collectors to make the institution a part of their estate planning, the museum’s money has been focused on purchasing artists of color in the past two years.

Throughout the year, the museum offered several Digital Drink + Draw programs that presented the work of self-taught artists through a number of different lenses.

“What’s important for us is that we want to provide works of art that resonate with the people looking at them,” Busch said. “They can say, ‘that is a person who looks like me.'”

In a category of art so rooted in the mantra of “By the people, for the people,” the American Folk Art Museum’s mission then becomes straightforward: reach those people – all of those people. Unlike many other museums, the art needn’t change for the moment – it was made for this moment, and those ahead.

For additional information, www.folkartmuseum.org.