Author, curator and educator John Beardsley has penned a monumental volume to anthologize the life and work of self-taught American artist James Castle (1899-1977). Presented in collaboration with the James Castle Collection and Archive and Yale University Press, the title presents more than 546 illustrations spanning the artist’s work and life, over two-thirds of which have never before been published. Beardsley’s exploration into the artist’s oeuvre fits into James Castle: Memory Palace, an autobiographical visual record that leads us through the very rooms that the artist inhabited by examining the storied works he left behind.

It strikes me that there is not a lot known of James Castle. Let’s start with what we do know.

We know a lot about his outward life. He was born in the mountains of central Idaho and was deaf from an early age. As a young man, he spent five years in a school for the deaf, living away from home. In his 20s he moved to a place near Star, Idaho. In his 30s he moved to the outskirts of rural Boise where he spent the rest of his life. We know he made art from an early age and we know most of the art that survives is from his later years, the ones he spent in Boise. His art practice diversified dramatically from drawings that he did with homemade ink made with soot and saliva and colored ink he made from soaking crepe paper in water. We know he started making constructions and playing with letters and alphabets and appropriating images that he found in the popular media. We know also that also lived with his family and was cared for by them his whole life: his mother, one of his sisters and his niece, who gave him a place to live and made it possible for him to pursue his art.

And what don’t we know?

We don’t know a whole lot about his inner life, what he thought, how he felt. He was able to communicate some through sign language with his family, especially one of his sisters who was hearing impaired. But he didn’t leave any kind of written record of his emotional life or his intellectual life. We really only know of his inner life through the visual evidence, through the art he produced. I think of it as a sort of visual autobiography, a stand in for a spoken record that most people provide of their life.

Did he thrive in school?

I would say not. The education of deaf people at the time was dominated by a theory called Oralism. Shaped by ideas of eugenics, some educators, including Alexander Graham Bell, thought that deaf people ought to be mainstreamed as much as possible. They didn’t want deaf people creating their own communities, so they wanted them to lip read and speak, so they could function in the dominant culture. Learning to speak is hard enough if you’ve heard language, but for people born deaf as Castle apparently was, it’s very hard. So he either couldn’t or wouldn’t learn to speak. When he started at the school, all instruction was spoken. So although he spent five years there, saw a lot and learned a lot, and subsequently used some language, especially in its written form, I don’t think he thrived in school.

Does his disability define his work?

No, I don’t think so. You can’t look at his work and say “this was the work of a deaf person.” But at the same time, there’s an idea in disability studies about Deaf Gain, that deafness is a form of sensory and cognitive diversity, and that deaf people create a more diverse world through special aptitudes in things like visual, tactile and spatial processing. Perhaps even more to the point, a disability scholar, Brenda Breuggemann, has written about Deaf Eyes, suggesting that there is a particular acuity that comes through intensified visual processing. So you can’t look at this work and say “it’s the work of a deaf person,” but it is interesting to look at it from the perspective of Deaf Eyes or Deaf Gain. There’s a heightened visual awareness evident in his work that may be a function of his being deaf. There is a more compensatory model in the work of Oliver Sacks, who suggests if you have a disability of some kind, you compensate for it in heightened skills in other areas. But that idea has been eclipsed by the idea of Deaf Gain, which sees it not as compensatory but as positive.

Untitled (farmscape with corral fence) by James Charles Castle (1899-1977), no date. Found paper, soot, crayon, 5¼ by 7-1/8 inches. ARCV61-0253 ©James Castle Collection and Archive, all rights reserved.

Do you believe his deafness ultimately funneled his attention to art?

Who knows? He was clearly aware of the visual and spatial characteristics of his environment. It may just be how he was inclined and he may have been inclined that way anyway had he not been deaf. I think it’s much more fruitful to think about his work in terms of memory than deafness. What he did was pay extraordinary attention to the environment around him and remember that with incredible intensity. And then reproduce it years later in drawings and constructions.

There’s a striking work in the book where he drew a figure with a head in the shape of a fist, the sign for dumb. How was he treated in his community?

For the most part, it seems he was pretty protected by his family. As a young man, he probably experienced the kind of cruelties we all do – everyone gets teased at one time or another, and it seems he experienced that sort of indignity. And he was probably aware of it, but there’s not a whole lot of evidence in his work that he felt either teased or persecuted, there are just little hints of it here and there. Slowly, he gained recognition as an artist in terms of the way people perceived him.

Define the idea of a memory palace for our readers.

The memory palace refers to an ancient technique for enhancing memory; it goes back at least to Cicero. The idea is that if you want to remember something, you create an architectural space in your mind and place images or objects in it that would remind you of things. When you want to remember something, you revisit that room and the images or objects will trigger memory. The more complicated something was that you wanted to remember, the more of an edifice you would need to construct in your own head. Ultimately this mnemonic technique came to be designated as a memory palace, and it has persisted into the present. People with highly superior memories apparently still use this technique.

Can you give a brief overview of Castle’s rooms?

I’m not sure that Castle knew of this technique, but it became for me a really useful way into his work – a way of focusing attention on his memory, but also a way of drawing out themes. So I assigned different aspects of his work to different rooms and moved through it as if through this series of rooms. I first talk about his life, and then the way he worked, and then I put all of the outdoor images into one room, the indoor images into another, all the figures and objects into a third, all the works that involved text letters, numbers and symbols into a fourth, and then his transcriptions, his copies and improvisations on found images into a final room.

Untitled (interior with figures) by James Castle (1899-1977), no date. Found paper, soot, 4¾ by 5¼ inches. CAS14-0228 ©James Castle Collection and Archive, all rights reserved.

How did memory come to play such an important role in his work?

This involves the question of why any of us remember things. For some people, memory is a way of registering joy or trauma, for some it is a way of sharpening intellectual skills, and for some people it may be a genetic disposition. It is hard to say why Castle was so engaged with memory, but I think it has something to do with the absence of conventional written or spoken narratives in his life. We all tell stories as a way of bringing our past to life, of constructing a coherent self, so I see Castle’s engagement with memory as a way of affirming his identity, creating an autobiography told through images rather than words.

Besides his drawings, are there any indications he had the exceptional memory of a savant?

I don’t think you would describe him as a savant. There’s something called Highly Superior Autobiographical Memory, and I think that idea fits Castle better. I think he had an incredible memory for the places and people of his own life. He kept returning to those images of places and people as a way of holding the past in his mind and sharing his personal history with his audience, which initially was quite small – his family and neighbors – but ultimately grew. It was a way of keeping his past alive, much as we retell stories.

Of his body of work, how much has likely been lost from his earlier years?

Nothing is dated, so we don’t know for sure when anything was made. The family picked up and moved twice, and probably a lot of stuff was left behind. This is partly a function of the way he handled his work. He often hid it away. He would tie it up in bundles or put it up in shelves or in the rafters of barns or in the walls of buildings. So when they moved, a lot of work may have been left behind inadvertently. He may not have even known they were moving and wouldn’t come back so he may not have felt a necessity to take it. In any event, most of what survives was made and stored away during his years in Boise.

Tell me about the bundles. What do they represent? Why did he bundle his works?

They were a storage device. They were often filled with the day’s work-at the end of the day he would bundle it up in the cloth, tie it with twine and put it on the shelf somewhere. In a way you could look at them as diaries, the visual notations of that day. They are not organized into particular types of work, just what he did on that given day. He was very conscientious about saving and storing his work, and this was one of the ways he did that.

Untitled (pram construction) by James Castle (1899-1977) no date. Found paper, soot, string, 18 by 14 inches. CAS10-0316 ©James Castle Collection and Archive, all rights reserved.

Was there a method to storing?

No, it seems to be just every available surface and any available space.

Did all works end in bundles?

No. The bundles are usually smaller things, so the constructions and the larger drawings and some of the texts would never have been in bundles. He made hundreds of tiny flipbooks, and those along with some of the small drawings wound up in bundles. But some of the constructions are two or three feet in size so they never would have been in the bundles.

Does the archive still open bundles?

The archive still has the bundles, but most have been opened and examined, and then rebundled.

Would he ever open a bundle after he wrapped it?

He certainly revisited ideas and images, but I think he remade them from his memory instead of referring back to stored images. He might have reopened them, but not to rework them or to draw from them. He was always drawing from his memory and imagination.

Was he open about his works with others?

Yes, he enjoyed sharing his work with people when his family had visitors, he’d bring work in to show everyone. He would be gratified when they were interested and irritated if they weren’t. I think he was aware of the growing interest in his work, and he had a few exhibitions in his lifetime. There’s a drawing of an exhibition at the Boise art gallery, now the Boise museum. I think he was happy to share his work. I wonder whether in his mind he was sharing art or rather sharing his life story. Did he think of it as art or as a narrative, or both?

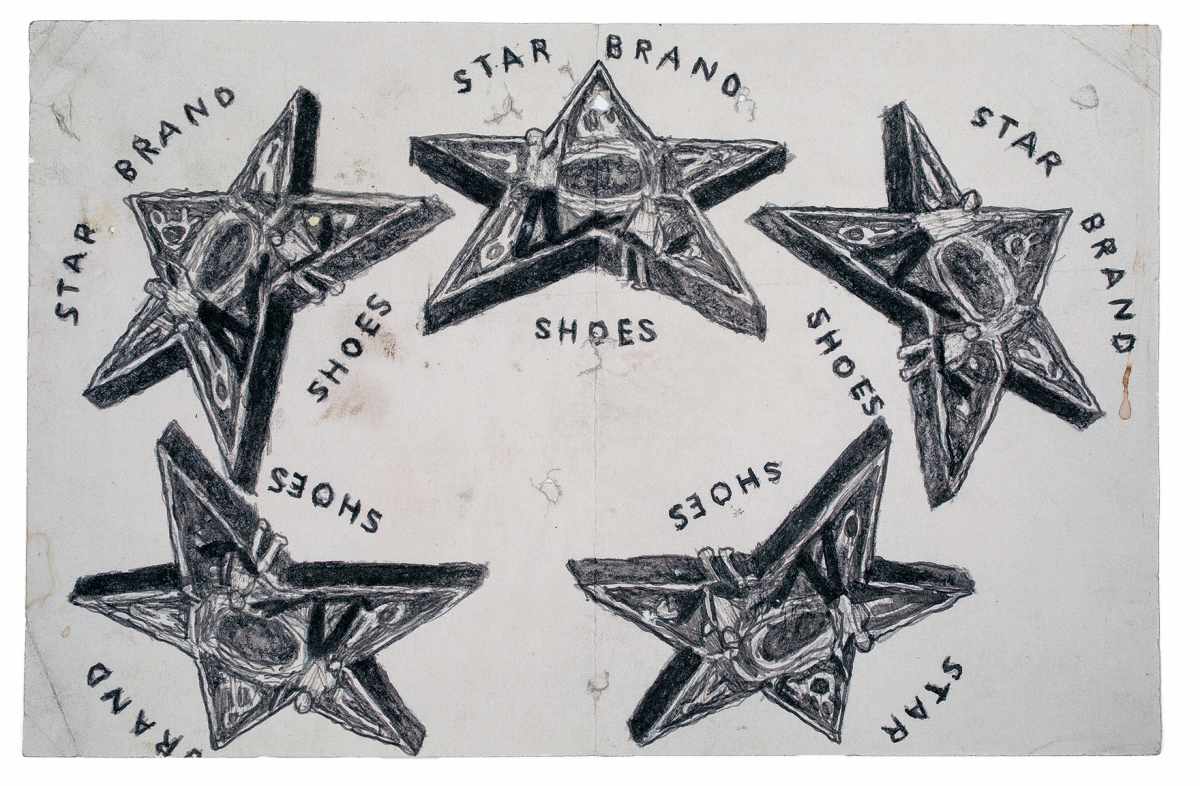

Untitled (Star Brand Shoes) by James Castle (1899-1977), no date. Found paper, soot, 7 by 10-7/8 inches. CAS09-0373 ©James Castle Collection and Archive, all rights reserved.

When do the constructions begin for Castle?

As far as anybody knows, he was making the constructions the whole way along. A lot of them are images of things he would remember from his childhood. Ducks, chickens, turkeys. Many of them are clothing, including shirts and jackets. Some of them are baby buggies, domestic implements like cups and bowls. We don’t know when they were made, but they certainly harken back to his earlier life.

Did he ever obtain access to better materials and change his work?

He had access to better materials, but he seemed to prefer things he could collect himself. So he stuck with matchboxes and milk cartons and cardboard, the humble materials he had always worked with. And he added to that magazine illustrations and advertisements and things he salvaged from print culture. He seems really to have preferred that because he stuck with it to the end.

Can you speak to his various modes of representation?

There’s an interesting way in which you can see the whole history of art in the Twentieth Century recapitulated in his work. Some of his images are incredibly realistic, some of them are more gestural and loose, even expressionistic, some are entirely abstract. There are elements of surrealism, people with bicycle wheel heads or television heads. There are text-based works that seem entirely conceptual. So you have a sense of him experimenting in an extraordinarily wide range of ways and really being incredibly inventive in terms of his materials, his subject matter, and his approach to representation. The point is not that he looked at other art or was somehow dilettantish; this was instead an expression of a really experimental imagination. He seems to have been driven by a what-if mentality, driven to invent and explore in as many different ways as he could.

Is Castle’s entire body of work an exploration of time and place?

For the most part, it’s an exploration of his time and his place. His lifetime and his place in the world. But I don’t think that accounts for all of it, because there were also imaginative places that he visited. That is evident in the text-based works. There are narratives that begin to emerge in the text-based works, recurring illustrations of different characters – the writings beginning to take on a novelistic character with them. So yes, it’s about time and place, but some of it is half-remembered and half-imagined.

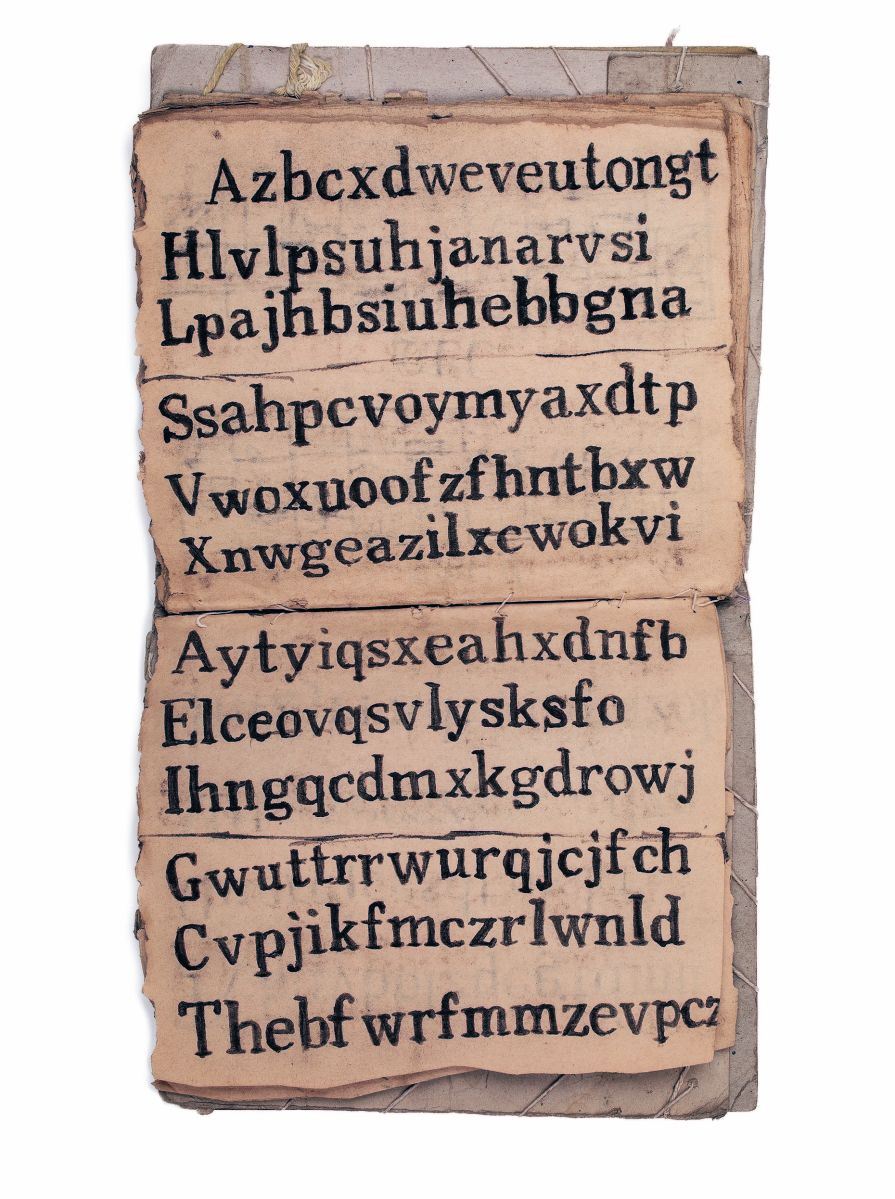

What do you find notable about the text-based works?

Most of them aren’t comprehensible in the usual way. Some are letters you recognize; some are drawn from Greek or Russian alphabets. Still others are entirely invented. Sometimes letters are in pairs or long strings. There’s a poetic or narrative impulse in the way the letters are placed on the page or repeated in lines, but they are completely inexplicable. It is like Castle invented his own language, but he seems to have been as interested in how it looked as in what it might have meant.

Untitled (Post Toasties) book by James Castle (1899-1977), 96 pages, no date. Found paper, soot, string. CAS16-0197 ©James Castle Collection and Archive, all rights reserved.

Are any images more prolific than any others?

There are some he returned to again and again. The landscape from his home in Garden Valley. Certain rooms: a couple different attic rooms, bedrooms and kitchens. There are details of objects in those rooms that also recur. There’s a whole set of images of doors, marking the transition of inside to outside. And then there are images that appear to illustrate the places Castle worked and displayed his work to others. Most of the recurring images have this incredible autobiographical character to them, the places he inhabited, the landscapes he lived in, the places that he worked.

What about mediums?

The drawings, many are done in this ink he made himself of soot and saliva, but not all. There are a number of colored inks he made and he applied the inks with a variety of different tools, most of which were homemade: fine pointed or blunt pointed sticks, rags that he used for ink washes. So not only did he make his own media, he also made his own implements.

Was there anything released in the book that had not been known?

There’s a lot of work in the book that hasn’t been seen before. About two thirds of the images in the book have not been published before, some from private and some from public collections. There are biographical details that haven’t been published before, from archival interviews we drew on. The book is an effort to present a complete picture of Castle’s life and work.

What did you learn through your research?

Castle kept opening new doors, new areas of history for me. The history of homesteading, the Idaho gold rush, the fascinating and disturbing politics of deaf education, the neurology of memory, the idea of Deaf Gain and Deaf Eyes. I kept discovering new ways of thinking about Castle and new areas of investigation. The subject really kept surprising me.

Ed Note: James Castle: Memory Palace is available through Yale University Books or Amazon for $65 hardcover.

-Greg Smith