Erica Wilson photographed in the 1960s by Louis S. Davidson. Courtesy of the Nantucket Historical Association.

By Laura Beach

WINTERTHUR, DEL. AND ONLINE – If you have ever wondered what kind of business might be developed by running small display ads in the back pages of The New Yorker, ponder no more. For roughly two decades beginning in 1962, Erica Wilson (1928-2011), a British-born stitcher educated at London’s Royal School of Needlework, advertised her talent as a teacher of embroidery, offering a series of correspondence courses, books, kits and, tantalizingly, the opportunity to study with the authority or her surrogates at her Madison Avenue atelier, her rambling Park Avenue apartment or the hydrangea-strewn Nantucket getaway she repaired to for several months a year with her husband, furniture designer Vladimir Kagan (1927-2016), and their three children.

The New Yorker ads were far from Wilson’s most visible form of promotion – the woman sometimes called “the Julia Child of embroidery” or the “First Lady of stitchery” was nothing if not a master of what is now called cross-platform marketing – but they encapsulated Wilson’s essential genius. By providing simplified techniques, easily assembled kits and step-by-step instruction, some of it from afar, Wilson made a classy, high-brow, Anglophile pastime accessible to far-flung and mostly middle-class consumers. Much like Martha Stewart, the lifestyle goddess who would follow her, Wilson dolloped out aspirational lessons on taste and creative fulfillment to an audience eager for instruction.

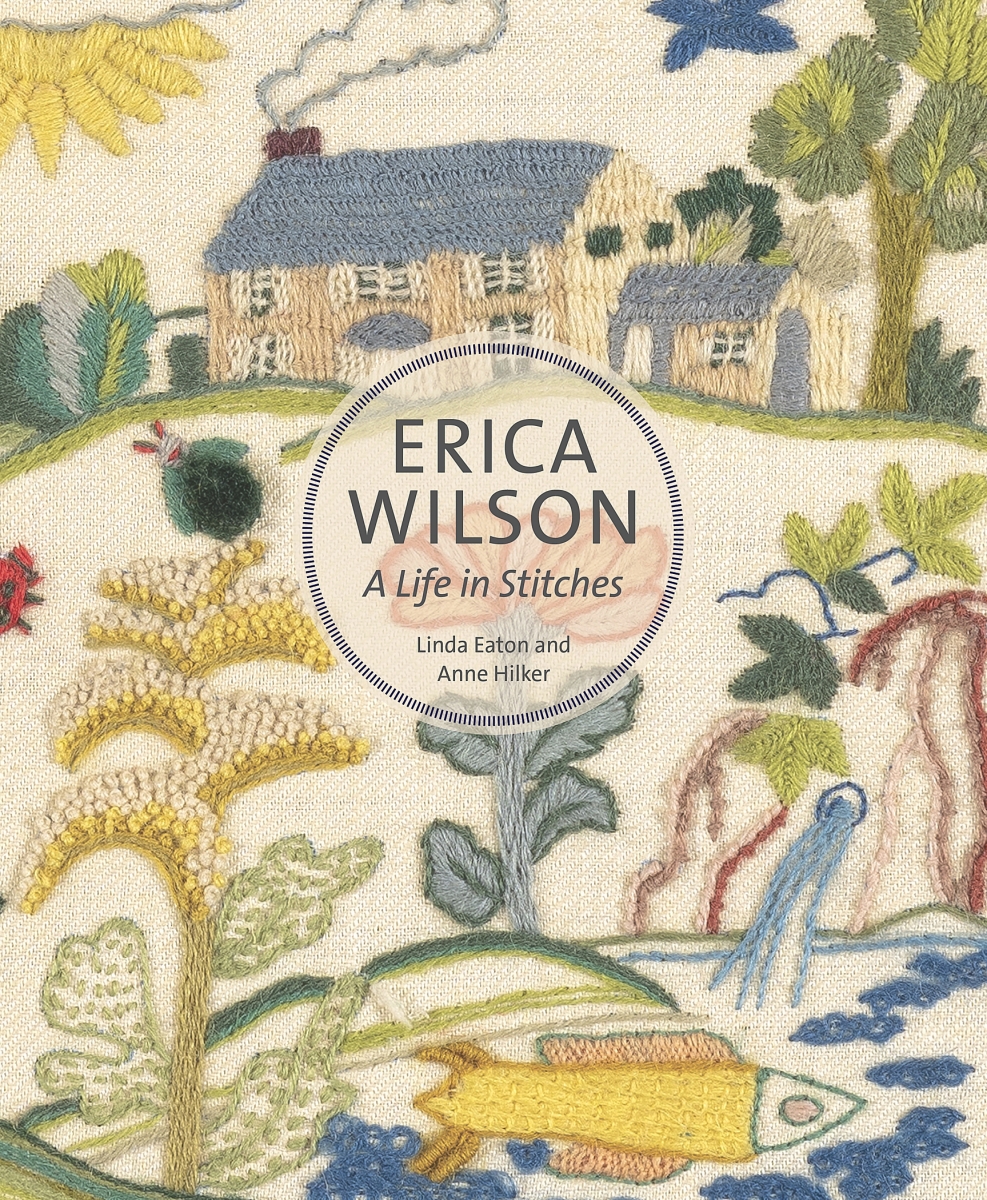

The needlewoman and her popularizing influence are the subject of a groundbreaking online exhibition at Winterthur Museum, Garden and Library and the related book, Erica Wilson: A Life in Stitches, written by organizing curators Linda Eaton and Anne Hilker and published by Winterthur late last year. Eaton, who retired in December after a stellar career as the John L. and Marjorie P. McGraw director of collections and senior curator of textiles at Winterthur, has long delivered fresh insight into even the most settled subjects. In documenting the life of Erica Wilson, she explores an avenue of scholarship still in its infancy, needlework’s popular manifestations in the United States in the second half of the Twentieth Century. Through Eaton’s efforts, Winterthur in 2015 received from the Kagan family a selection of Erica’s embroideries, ranging from 1940s student pieces to her later work, plus designs and some of the inspirational items she collected on her travels.

Illustrated in Erica Wilson’s Embroidery Book, this design was adapted by Wilson from an embroidery by Vladimir Kagan’s sister. This beginner’s project in crewelpoint is described as a sampler because it uses a variety of stitches. Winterthur Museum, Gift of The Family of Erica Wilson, 2015.0047.015.001.

Eaton’s co-author, Anne Hilker, a former attorney and current doctoral candidate at Bard Graduate Center, began her seven-year immersion into the life and work of Erica Wilson while studying for her master’s degree at the Cooper-Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. Kagan, called Vladi by those who knew him, was looking for interns to catalog his late wife’s archives. Hilker accepted the challenge.

“I worked primarily in the couple’s apartment, where Erica’s most treasured pieces were. I traveled a dozen times to her New Jersey warehouse. It was a massive project. The archive contained more than 3,000 pieces, including documentation drawings, heat transfers, frames, supplies, inventory for kits and pieces for magazine commissions. There were computations for wholesale costs and retail prices. I found a script, meticulously annotated in Erica’s handwriting, for one of her VHS tapes that came out in 1986,” Hilker recalled recently by phone.

Originally from California, Hilker was first introduced to Wilson through her kits, not the television series Erica, produced by WGBH Boston between 1971-72 and 1975-76 and broadcast on PBS stations nationally. On trips to New York City in the 1980s, Hilker visited the Erica Wilson shop at 717 Madison Avenue between 63rd and 64th Street. The second-floor showroom with big picture windows overlooking the street below was cozy and colorful, warmly traditional but also fashion forward, evolving with Erica as she embraced a crafts community that changed with her.

Erica Wilson: A Life in Stitches by Linda Eaton and Anne Hilker places the entrepreneur’s life within the broader context of the Twentieth Century crafts revival.

Hilker, who later participated in one of the seminars the stitcher offered on Hilton Head Island in South Carolina, says the needlewoman was charming, personable and utterly unassuming. Yet Wilson remains “personally unknowable,” Eaton and Hilker conclude, writing, “Too busy to leave notes and recollections – other than, say, stage directions for her videotapes – or, perhaps, not inclined to do so, her private thoughts and emotions now must always remain that way…. More than a year after her death, in December 2011, a needle remained in a crewelpoint composition and her tools – at least twenty, of all shapes, sizes and origins – in an unmarked plastic shopping bag. Her colored pencils sat sharpened at the ready in the dining room. Erica was never finished.”

Complicating the story, Wilson’s public persona was thoroughly joined with that of her husband. Born in Tidworth, England, to a British military colonel and his wife, Wilson spent her earliest years in Bermuda. At the Royal School of Needlework between 1945 and 1948 she learned the traditional techniques that provided the foundation for her later designs and teachings. She came to New York as an instructor in 1954 at the invitation of Margaret Parshall, who ran an embroidery school in the affluent Hudson Valley town of Millbrook. Dressed as a poodle, she met Kagan at a costume party at the Architectural League in New York City. The couple married in 1957.

Already a noted furniture designer when they met, Kagan’s own celebrity was in time eclipsed by that of his wife, who soon launched her own business and became the family’s chief breadwinner. Kagan’s managerial talents – he did everything from create diagrammatic drawings for Wilson’s designs to entertain bored husbands at her Nantucket seminars – had much to do with the enterprise’s success.

“Elizabethan Lady,” circa 1973. Wilson used versions of this design to introduce chapters on crewelwork, blackwork and needlepoint in Erica Wilson’s Embroidery Book, published in 1973. Winterthur Museum, Gift of The Family of Erica Wilson, 2015.047.005.002.

“It was an amazing marriage of skills and drive. As much as we can describe Erica in terms of her talent, ingenuity and passion for needlework, I don’t think that would have been channeled into the commercial and communication success that it was without Vladi. They were well-matched, had a great sense of the moment and seemed happy to share in each other’s successes,” Hilker says. In only a handful of instances did Wilson create decorative coverings for furniture made by her husband.

As Eaton and Hilker relate in an opening chapter on embroidery in the United States between 1876 and 1950, needlework supplies and training were once staples of American department stores, which allotted ground-floor space for products subsequently displaced by perfumes and cosmetics. Eaton remarks, “there is a much, much bigger story here. Cynthia Fowler has written about artists such as Marguerite Zorach who used embroidery, but there were huge numbers of primarily women embroidering before Erica arrived. I hate to call them amateurs because many of them exhibited their work. It’s wrong to think that nothing happened in the first half of the Twentieth Century.”

Wilson developed her first correspondence course at the request of stitchers allied with Colonial Williamsburg in Virginia in 1959. Around 1962 she received an advance of $100,000 from the yarn manufacturer Columbia-Minerva to produce kits containing their yarns to distribute to their retailers. Erica’s own kits, which she continued to assemble, used superior Appletons wool, favored by the Royal School of Needlework. Wilson launched her first mail-order catalog in 1965, initially packaging kits from Kagan’s furniture factory on 81st Street at East End Avenue.

“Country Life,” one of Wilson’s perennially popular designs, was introduced as part of her line of Custom Kits in 1971. Over time, the motifs showed minor variations. Wilson got her inspiration from an embroidered picture in London’s Victoria and Albert Museum. The original kit used 50 colors and 30 different stitches. Winterthur Museum, Gift of The Family of Erica Wilson, 2015.0047.016.001A.

Published by Scribner’s in 1962, Wilson’s first book, Crewel Embroidery, was a best-seller. Crewel was the most popular technique Wilson taught, and it formed the bulk of her kit designs. Crewel’s use of wool yarn rather than silk floss made it easier for beginners to create bold designs with fewer stitches.

Wilson’s 21 books include Erica Wilson’s Embroidery Book of 1973. The entrepreneur also mailed a quarterly newsletter, The Creative Needle, to her customers.

Hilker notes, “It would be hard to duplicate her success today. It was the confluence of early television supplemented, importantly, by books and magazines. If you were a lone embroiderer you could find support. Erica did dozens of commissions for women’s magazines, and they were frequently covers. Magazines were more important than television in getting the kits into people’s hands.”

Almost as important as Kagan to Wilson’s success was Edith Scott Bouriez. Wilson’s friend for 50 years and her New York shop manager for 20, Edie, as she is known, instructed students, evaluated their work, organized seminars, led group needlework tours, some of them abroad, and was decisive in bringing the Kagan family to Nantucket, where Mary Ann Beinecke (1927-2014) founded and directed the Nantucket School of Needlery in the early 1960s. A summer visitor to Nantucket since 1953, Bouriez still teaches needlework at the Nantucket Historical Association’s 1800 House.

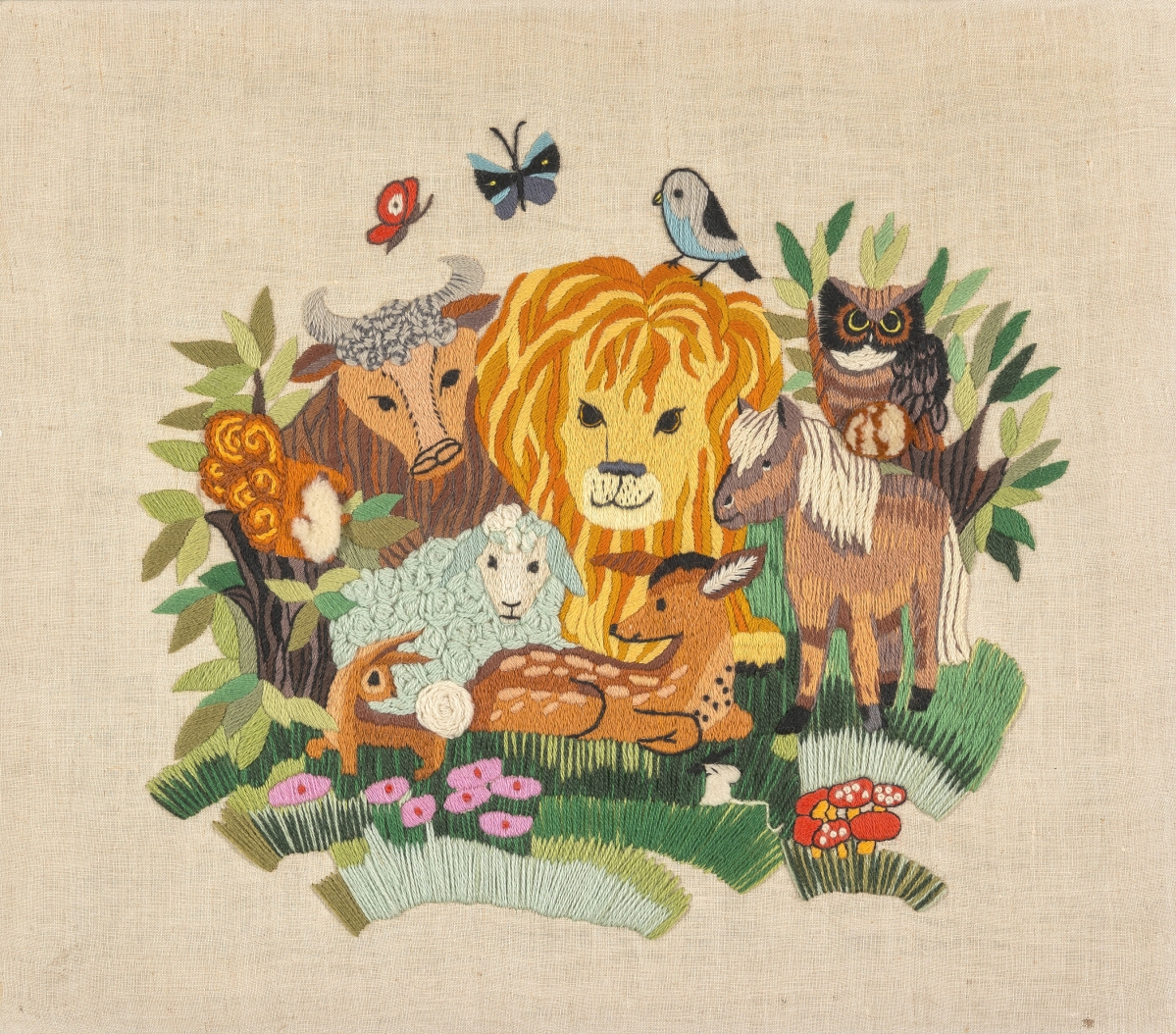

This picture is a liberal adaptation from one of Edward Hicks’ paintings “The Peaceable Kingdom.” Gift of The Family of Erica Wilson, 2015.0047.018.

“The first place Erica sold Appletons yarn was out of a Nantucket shop owned by Edie’s then husband, Hampton Lynch. Erica and Edie had friends in common, skills in common. It was another fine partnership,” Hilker remarks. Wilson’s Nantucket seminars ran from 1974 to 1984. While the Madison Avenue shop closed in 2005, the business Erica Wilson Nantucket continues under the direction of daughter Vanessa Kagan Desirio.

Fashion is fickle. Interest in needleworking peaked in the 1970s, with many hobbyists moving on to quilting and knitting. Wilson rode the wave gamely, rolling out new books on smocking, quilting, knitting and wearable art. She produced kits aimed at the crafts and clothing markets.

Today best known for curvilinear chairs and sofas emphasizing comfort without sacrificing style, Kagan rose to new fame with the resurgence of interest in Modern design. One of his most prominent fans is designer Tom Ford, who wrote the preface to Vladimir Kagan: A Lifetime of Avant-Garde Design, published by Pointed Leaf Press.

The market may have largely forgotten Erica Wilson, but her many fans have not. “The admiration and appreciation people have carried with them for Erica allowed us to do this book. She reached people in a way that was not limited to fiber, fabric and stitching,” Hilker reflects.

Working toward her teaching credentials, Wilson designed much of this silk and goldwork sampler herself, using prototypes she saw and sketched at the Victoria and Albert Museum. Winterthur Museum, Gift of the Family of Erica Wilson, 2015.0047.003.

Eaton adds, “I interviewed people who knew Erica, but also others who came after her. I was reminded by one person that in needlework you pass down the traditions you learn from your teacher, so there’s a continuous thread, if you will. I had not anticipated how many younger people share older audiences’ love of Erica Wilson’s designs.”

Highlighting items donated to Winterthur and others lent by the Kagan family, plus a clip from the Wilson’s PBS show, Erica Wilson: A Life in Stitches, the stitcher’s legacy may be toured online at www.winterthur.org. Paperback copies of the accompanying book are available here.

Winterthur Museum, Garden and Library is at 5105 Kennett Pike in Winterthur, near Wilmington. For information, 800-448-3883 or www.winterthur.org.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)