Installation image of “Birds of the Northeast: Gulls to Great Auks.” View it virtually at https://www.fairfield.edu/museum. Courtesy of Fairfield University Art Museum.

By Kristin Nord

FAIRFIELD, CONN. – The worldwide fate of birds since the 1970s has been increasingly dire: billions have vanished throughout Canada and the United States, and many species are threatened by the effect of climate change, the world’s over-reliance on pesticides and the loss of habitat. Migratory routes once replete with whooping cranes and songbirds have been casually littered with detritus. It’s an unfolding disaster that Connecticut Audubon has been working to address in various conservation efforts, but ornithologists nonetheless are chronicling a full-blown crisis.

Now on view through May 14, the Fairfield University Art Museum (FUAM) trains its lens on the avian history and plight. “Birds of the Northeast: Gulls to Great Auks” celebrates the majesty and diversity of birds within our midst, but also speaks with urgency about the ways in which our lives and diminishing bird populations are interlinked.

This exhibition marks the museum’s 10th anniversary and is an inspired blend of art and science, drawing upon the expertise from Fairfield University’s biology and art history departments for a collaborative effort that has become a trademark of Fairfield University Art Museum projects in recent years. It has been three years in the making, and is co-curated by museum director Carey Weber, and three members of Fairfield University’s biology department – Brian Walker, PhD, Jim Biardi, PhD, and Tod Osier, PhD.

“Creating an interdisciplinary exhibition, like this one, is really only possible on a university campus or through a collaboration of an art museum and a natural history museum,” Weber said. “By working with biology faculty as my co-curators (and with the assistance of a biology student) we were able to build upon the art that I’ve selected with additional, important components. For that reason, people who visit this exhibit will encounter scientific labels and art historical wall text as well as specimens that are generally behind glass in natural science museums.

“Most natural history museums will not lend study skins/specimens of extinct birds because they are simply too rare and valuable. The addition of study skins of living common birds to our exhibition serves to introduce viewers to the concept that birds must be treasured and not taken for granted, and to educate viewers about how important skins like these are to ornithological study,” she said.

And so the skeleton of a Great Auk makes its striking appearance as both sculpture and relic, and thrusts us into imagining a time when these awkward flightless birds dutifully tended to their sole once-a-year egg during its 44-day gestation period.

“The Art Bridges Foundation has played a significant role in FUAM’S undertaking, financing the acquisition of a Matterport camera which allowed the museum to create a virtual 360-degree tour, and to underwrite Spanish translations of the materials to appeal increasingly to the region’s LatinX population. It has also paid to publish the student-generated guide to the birds routinely encountered on campus,” she said.

And the foundation enabled FUAM to borrow the Marsden Hartley painting, “Give Us This Day,” from Crystal Bridges, the Bentonville, Ark., museum founded in 2005 by Alice Walton, complete with crating, round-trip shipping and insurance for the painting, Weber added. The work, painted in 1938 during the years when Hartley had returned to reside in Maine, serves as the frontispiece for the exhibition. Wall text suggests that in its uncharacteristically symmetrical composition, Hartley has assembled his seagulls around a table, perhaps imagining the natural world’s “Last Supper.” With the designated seagull at the head of the table, one can’t help but think of Christ as a fisherman, overseeing the distribution of loaves and fishes in the famous biblical story.

Weber has also engaged a number of leading contemporary eco-artists for this project, and many of them infuse their works with references to famous works in art history. Some of the artists make reference to early depictions of The Lamentation, in which the Virgin Mary embraces the body of Christ. Walton Ford, who often opts for satire in his art, situates the now-extinct Carolina parakeet in the scene painted in Benjamin West’s, “The Death of General Wolfe.”

“Dying Words” by Walton Ford, 2005. Six copper plates, hardground etching, aquatint, spit bite aquatint, drypoint, scraping and burnishing on white BFK Rives paper. Published by Blue Heron Press, New York. Lent by Joshua Rechnitz. ©Walton Ford.

Traversing the Bellarmine Hall Galleries we encounter birds perhaps as we’ve come to expect them, in classic portraits and in natural settings. But much as there are classic works by renowned Eighteenth Century artist-naturalists Alexander Wilson, John Gould and Karl Bodmer, new works project us into darker aspects of this inquiry. Emily Eveleth captures a brilliant red cardinal – in death, for instance – while Morgan Bulkeley paints mourning dove masks in his compositions that are traditionally worn in the South Pacific mourning rituals.

Bulkeley has written, “I see in nature and in the best of humanity an incredible beauty; but I also see in our technology and aggression a will and ability to destroy that beauty, either actively or inadvertently.”

Paul Villinski’s fantastical birds, sculpted from recycled vinyl albums, set the viewer off on a colorful and surprisingly mystical meditation on migration, while leading Connecticut artist-naturalist James Prosek has loaned a watercolor of a great blue heron, as well a work that depicts a wood duck in flight. In the second work, Prosek employs the numbering device and silhouette motif originally used by Roger Tory Peterson in his field guide.

An oil painting of a Labrador duck is on loan from the Extinct Birds Project, which emanated from Alberto Rey’s encounter with a drawer of extinct birds at the Roger Tory Peterson Institute of Natural History in Jamestown, N.Y.

“Long Playing Birds” by Paul Villinski, 2020. Vinyl LP records, stainless steel wire. Lent by the artist, courtesy of Jonathan Ferrara Gallery.

“On the clean white paper were the bodies of seven extinct birds and around a dozen other threatened species,” he writes. The chance encounter set Rey off on a project to investigate the lives and extinction of 17 bird species as well as the ornithologists who collected the specimens.

One wall of the Ballarmine Hall Galleries is ablaze with Matthew Day Jackson’s four-color, four-plate etchings, created in response to the poet Sara Teasdale’s “There Will Come Soft Rains.” Teasdale’s poem was written in 1920 in the aftermath of The First World War and The Great Epidemic of 1918. For this portfolio, Jackson has reworked copper plates etched with a 1930s edition of Audubon’s Birds of America and layered them with found images. In this manner he asks us to meditate upon the after-effects of nuclear disaster, climate change and loss of habitat. When we pick out the newspaper image of the Ferris wheel in the town of Pripyat, Ukraine, an iconic casualty of the Chernobyl meltdown, or see in a detail from Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s “The Triumph of Death” in one of Jackson’s other plates, we understand we are being asked to consider what Jackson has dubbed, “the horriful,” our human capacity “to create both beauty and horror.”

Traversing the campus grounds with the university’s new bird guide in hand, a visitor can peruse two decades of the ornithology students’ dutiful recordkeeping. They have assembled an impressive list of some 124 resident and migrant birds that can be encountered on campus. The list, which ranges from hawks and great and snowy egrets to a succession of ducks, mallards and songbirds, is a reminder that Fairfield itself lies along a major avian highway. Mabel Osgood Wright’s first bird sanctuary, a 7-acre exemplar of planting and habitat, just minutes away, has been helping migratory birds to rest and refuel every spring and fall for more than 100 years.

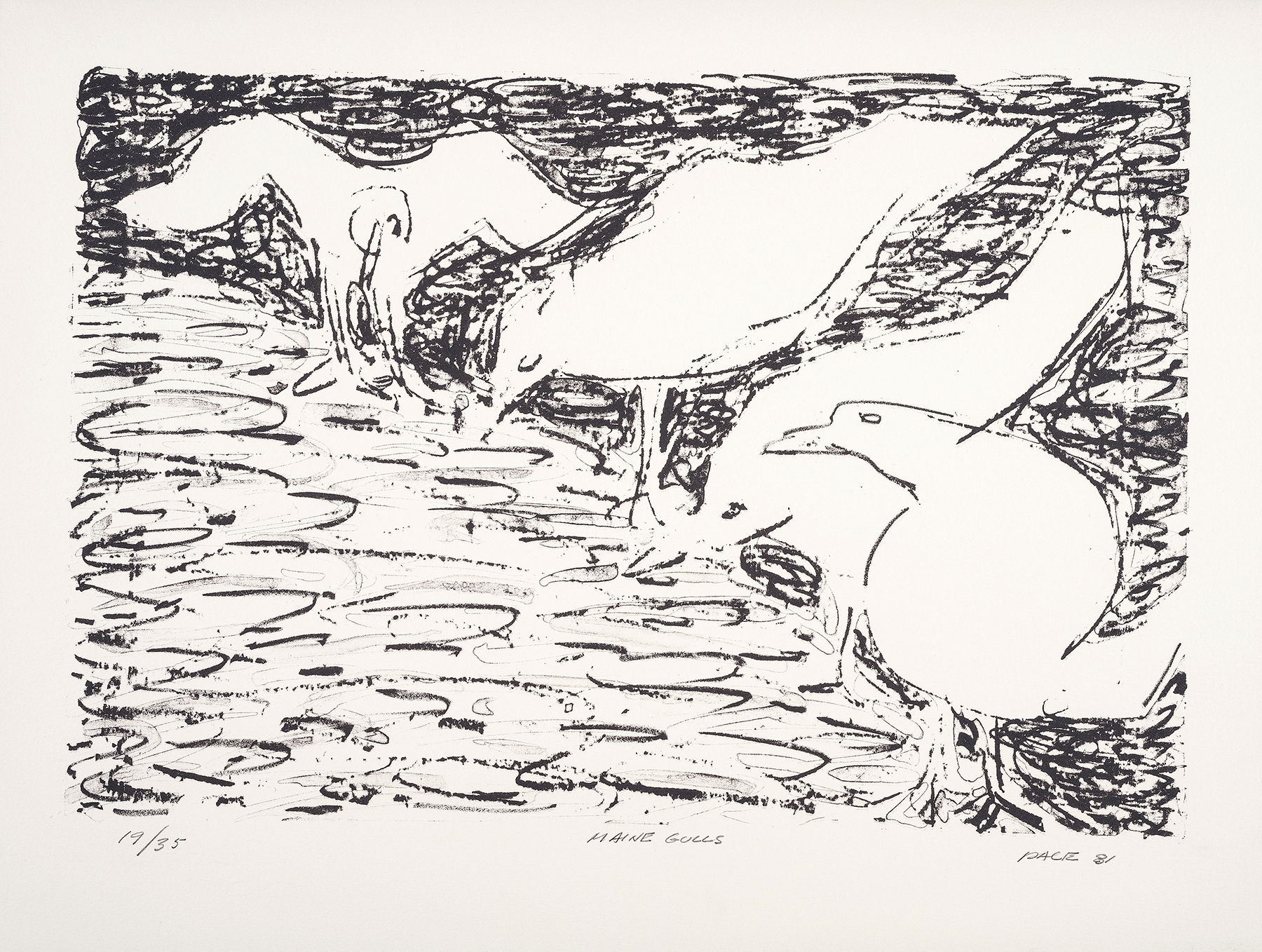

“Maine Gulls” by Steven Pace. Lithograph on paper. Fairfield University Art Museum, gift of the Stephen and Palmina Pace Foundation.

On the lawn in front of the University’s DiMenna-Nyselius Library, a cluster of bronze sculptures has taken up residence and function as a Greek Chorus on a recent grey winter’s day. They are part of Todd McGrain’s Lost Bird Project, one of a series of public memorials for North American birds that have been driven to extinction in modern times. Our Northeastern casualties: The Health Hen, the Carolina parakeet, the Labrador duck, and the passenger pigeon are here, and can be expected to exert a force during the coming months when all exhibition tours, in response to the pandemic, will be virtual.

Weber and her co-curators have worked diligently on FUAM’s online programming to offer what cannot be experienced in person. An impressive roster of guest lecturers, including Jonathan Weinberg, artist and professor at the Yale University School of Art and Rhode Island School of Design, and the renowned naturalist Douglas Tallamy, professor of Entomology at the University of Delaware, have been enlisted, with a final virtual lecture on John James Audubon to be delivered April 14 by Roberta Olson, curator of the New-York Historical Society, and professor of art history emerita at Wheaton College. FUAM has had significant success with its online programming, Weber said, drawing some 3,500 viewers last fall alone. But one can hope that with an exhibition of this caliber that people will have a chance to see it in-person as well.

To access the virtual tour, lectures and other programming, visit https://www.fairfield.edu/museum/birdsofthenortheast/. Or you may access the university’s YouTube channel: https://www.fairfield.edu/museum/watch-listen-learn/index.html?scrollto=videos

The Fairfield University Art Museum is at 200 Barlow Rd. For additional information, https://www.fairfield.edu/museum/ or 203-254-4046.