Installation view of “Supernatural America: The Paranormal in American Art” at the Toledo Museum of Art. Photo by Robert Cummerow, courtesy Toledo Museum of Art.

By James D. Balestrieri

TOLEDO, OHIO – Why is it that on those shows where some young, semi-literate group of gullibles goes a-hunting – for ghosts, or Big Foot, or UFOs, or Hodags – they all run the other way as soon as anything vaguely creepy happens? You see them running, the camera bouncing around in a nauseating way, grunts from the (not so) intrepid team, until…a safe distance from the phenomenon or apparition they claim to have encountered, they regroup and give us – after loops of commercials for reverse mortgages, which themselves seem like promises to take you back in time and unravel your mistakes – tantalizing bits of non-evidence of the thing they fled. Think about it, if you were hunting ghosts and you actually stumbled onto one, minding its own business in an abandoned insane asylum, wouldn’t you run towards it, to secure proof and expand the boundaries of knowledge?

Despite never having glimpsed a ghost, heard a spirit rapping, scented mimosa on the east breeze – watch the 1944 film, The Uninvited and then tell me those old black and white films can’t shiver a spine – or seen a light zag against the laws of physics in the night sky, despite all these nevers, as Fox Mulder once observed, “I want to believe.”

What is fascinating about all of the artists in “Supernatural America: The Paranormal in American Art” – the new exhibition making its debut this summer at the Toledo Museum of Art before going on tour at the Speed Art Museum and the Minneapolis Institute of Art – is that they not only believe in a world of spirits and things that go bump in the night, they face them with reverence and wonder rather than fear, welcoming emissaries from these other realms. Indeed, their art often depends on forming and maintaining strong, ongoing relationships with this hidden world that is nevertheless right beside our own.

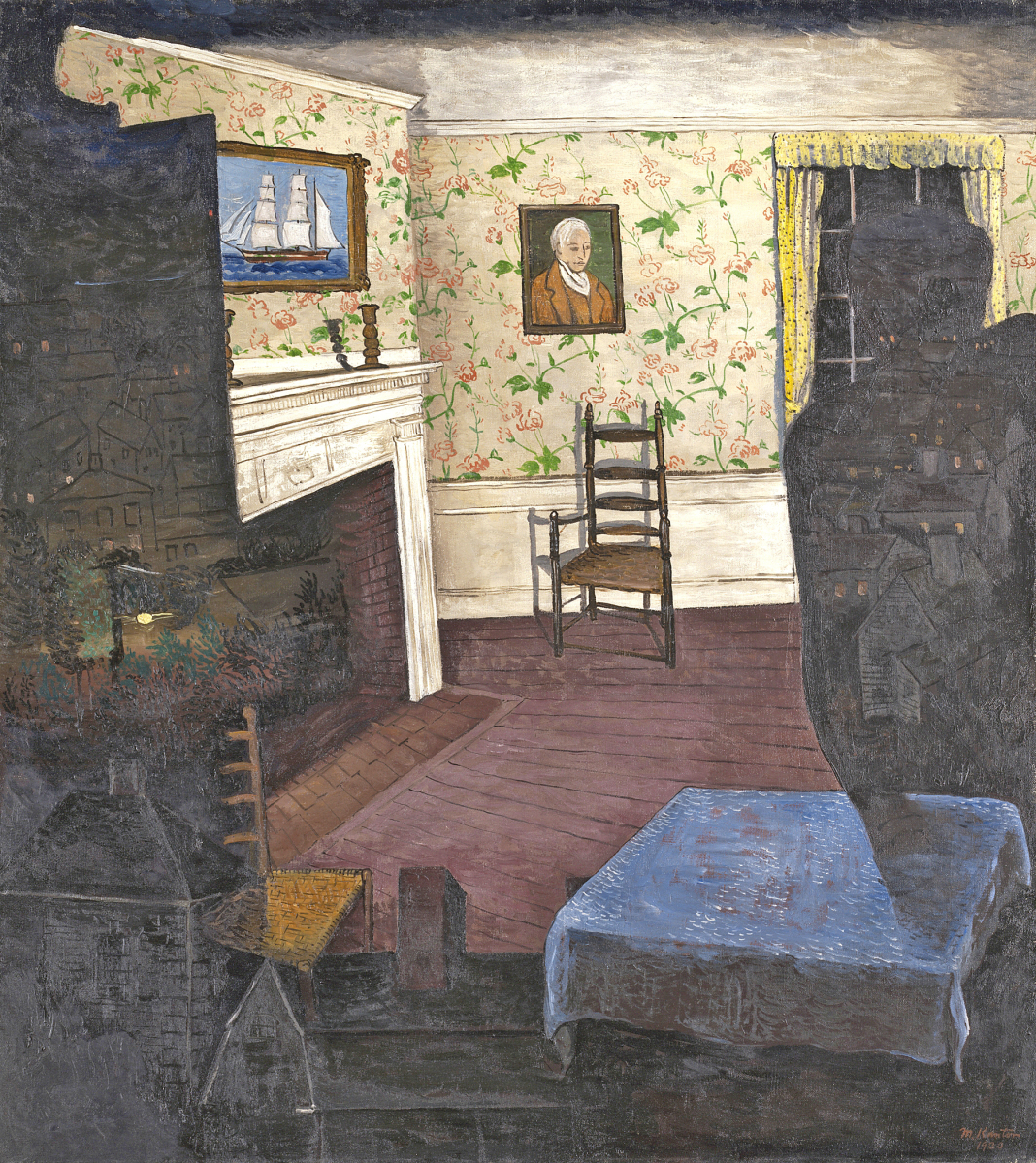

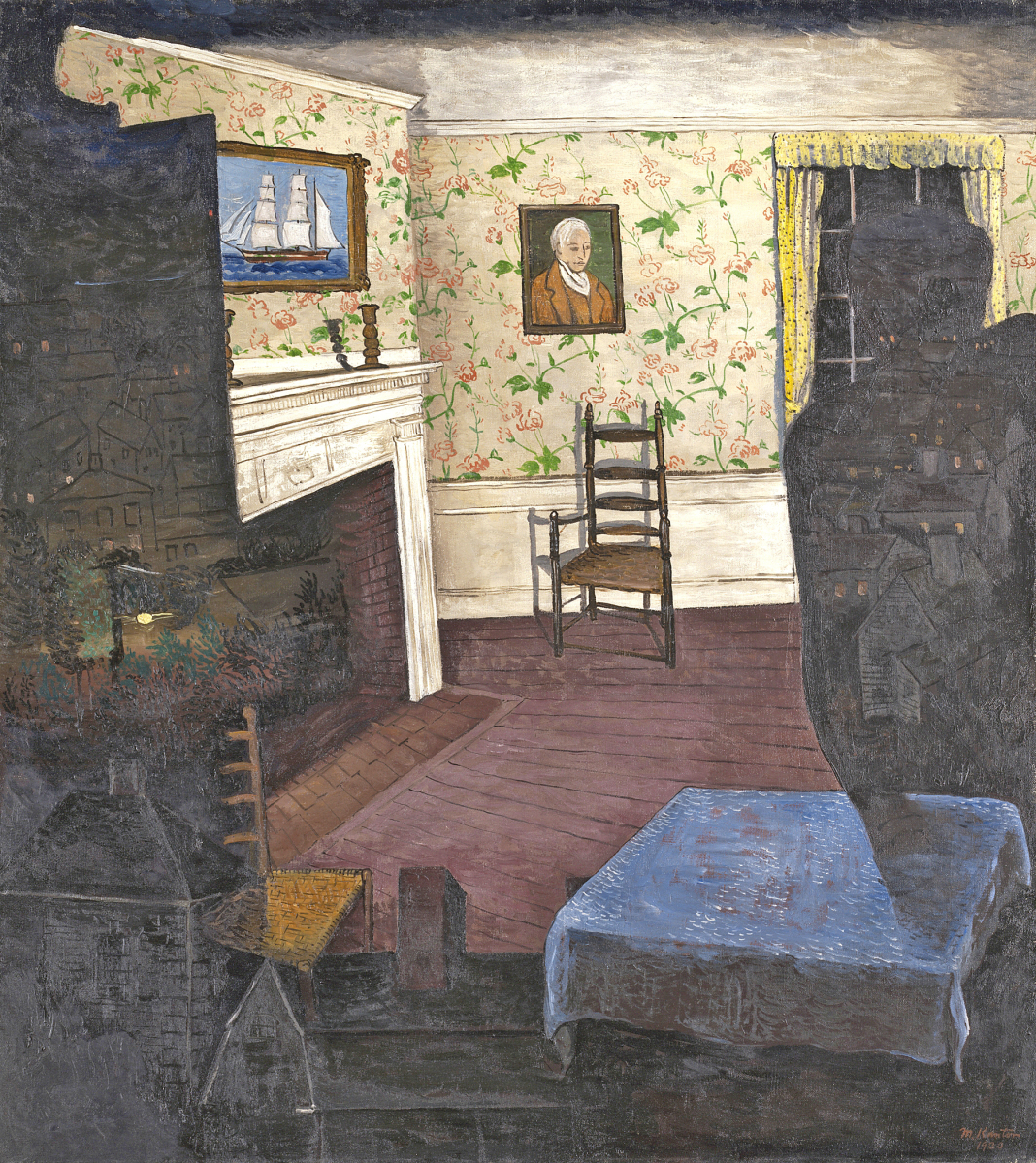

“Haunted House” by Morris Kantor (American, 1896-1974), 1930. Oil on canvas. Mr and Mrs Frank G. Logan Purchase Prize Fund. The Art Institute of Chicago. Photo The Art Institute of Chicago/Art Resource, NY. ©Estate of Morris Kantor.

What is astonishing about the exhibition – an exhibition that argues for a reappraisal of largely ignored spiritualist-artists who have been relegated to the silo of outsider art – is finding that so many canonical American artists believed that they channeled spirits. Among these, William Sidney Mount, James McNeill Whistler and Ivan Albright stand out. But why not? Behind all of our examinations of art and artists, behind all the history, social context and debates over meaning, hovers the specter of the ultimate speculation, that art chooses the artist, that the source of art, the impulse to make art, to persist in making art, is ineffable, unknowable, strange, alchemical, magical.

What is new, to me anyway, in this exhibition is the political dimension among these other dimensions. Spiritualism was a way to wrest control and agency from the marginalization experienced by women and people of color. As mediums between this world and angels, ghosts, and the spirits of loved ones or as conduits for great artists such as William Blake, Peter Paul Rubens and others, Spiritualists and “…the occult provided a path to asserting women’s subjectivity and creative autonomy,” wrote Rachel Middleman in the exhibition’s catalog. Elsewhere, Robert Cozzolino writes, “Trance is critical to understanding the relationship between power, creativity and religious authority in Spiritualism. Some mediums gave public discourses and religious/philosophical sermons in trance, others produced hundreds of pages of automatic writing. Trance enabled leading mediums like Cora Hatch to severely criticize mainstream Christianity, and it established the platform for suffragette Victoria Woodhull and free speech advocate Ida Craddock to publicly assert that women should have sovereignty over their bodies and social place as a human right and political cause. Trance opened a public space for agency in liminal territory where fluid bodies merged and worlds converged. In this space, female mediums exercised their intellectual and creative power autonomously before attentive audiences in domestic séance circles and large auditoriums.”

For Black Americans, this world must be transformed or, perhaps, escaped. As Bridget R. Cooks observes in her catalog essay, “In literary, musical and visual texts by Black Americans, faith in the supernatural functions as a means of survival.” Afrofuturist visions in visual art that emerge in the subway and street art of the 1970s-80s dovetail with the Spiritualist underpinnings in Betye Saar’s “The View From the Sorcerer’s Window” and find contemporary resonance in The Underground Railroad, Lovecraft Country, and the utopian African nation of Wakanda in Marvel’s Black Panther.

“Search for Rest” by Gertrude Abercrombie (American, 1909-1977), 1951. Oil on canvas. Collection of Sandra and Bram Dijkstra. Photo Sandy and Bram Dijkstra.

In the 2017 animation, Destinies Manifest, artist John Jota Leaños pits the enormous, Caucasian blond spirit of “America” or, perhaps, “Liberty” – quoted from John Gast’s 1872 painting, “American Progress” – against hosts of Indigenous peoples, spirits, symbols and spirit animals. Wherever the blond goddess reigns, however, the land is blasted, wasted, polluted, crisscrossed by highways and ruled by white supremacy.

Looking at the examples of feminist performance art as they attempt to connect the female body with the spirit of the natural world, or at works that strain against the artificial conventions and confinements of race, gender, sexuality, one sees the not-so-invisible hand of the patriarchy. Where religious art, located in institutionalized faiths, is widely accepted and studied, “In American art history,” Middleman writes, “the institutionalized gender discrimination experienced by women artists has been reflected and compounded by the discipline’s erasure of the spiritual and supernatural.” This sentiment might well extend to every other marginalized group, yet in this exhibition, it is almost as if the artists have decided to own Salem’s Tituba and Sarah Good, the “weird women” in Macbeth – and all the medicine men, shamans, witches – saying, “Fine, if this is where you put us, this is where we’ll build our temple and make our art.”

Perhaps it all goes back to fear. In his essay “Supernatural Horror in Literature,” H.P. Lovecraft – whose phobias of people of color, of women, of industrialization, to name a few, are well documented – wrote, “[T]he oldest and strongest kind of fear is fear of the unknown.” Lovecraft goes on, “But the sensitive are always with us, and sometimes a curious streak of fancy invades an obscure corner of the very hardest head; so that no amount of rationalization, reform or Freudian analysis can quite annul the thrill of the chimney-corner whisper or the lonely wood.” Conversely, Lovecraft might say, if you don’t fear the supernatural, it can have no hold over you. Further, if you can harness it, you can make it your ally. Unfortunately for most of his characters, they succeed in harnessing the supernatural only to find themselves scared to death by it. John Quidor’s “The Headless Horseman Pursuing Ichabod Crane,” painted in 1858 (perhaps the first illustration of Washington Irving’s Legend of Sleepy Hollow) hits me where I live, literally, less than a mile from the Old Dutch Church in the story. Through the lens of the exhibition, Ichabod Crane – scarecrow scaredy-cat, with his mixture of Puritan fundamentalist belief and penchant for ghost stories, becomes a comic take on a Lovecraft character – his belief that Brom Bones’ tale of the headless horseman has somehow manifested the horseman, birthing the source of his fear and his ultimate fate.

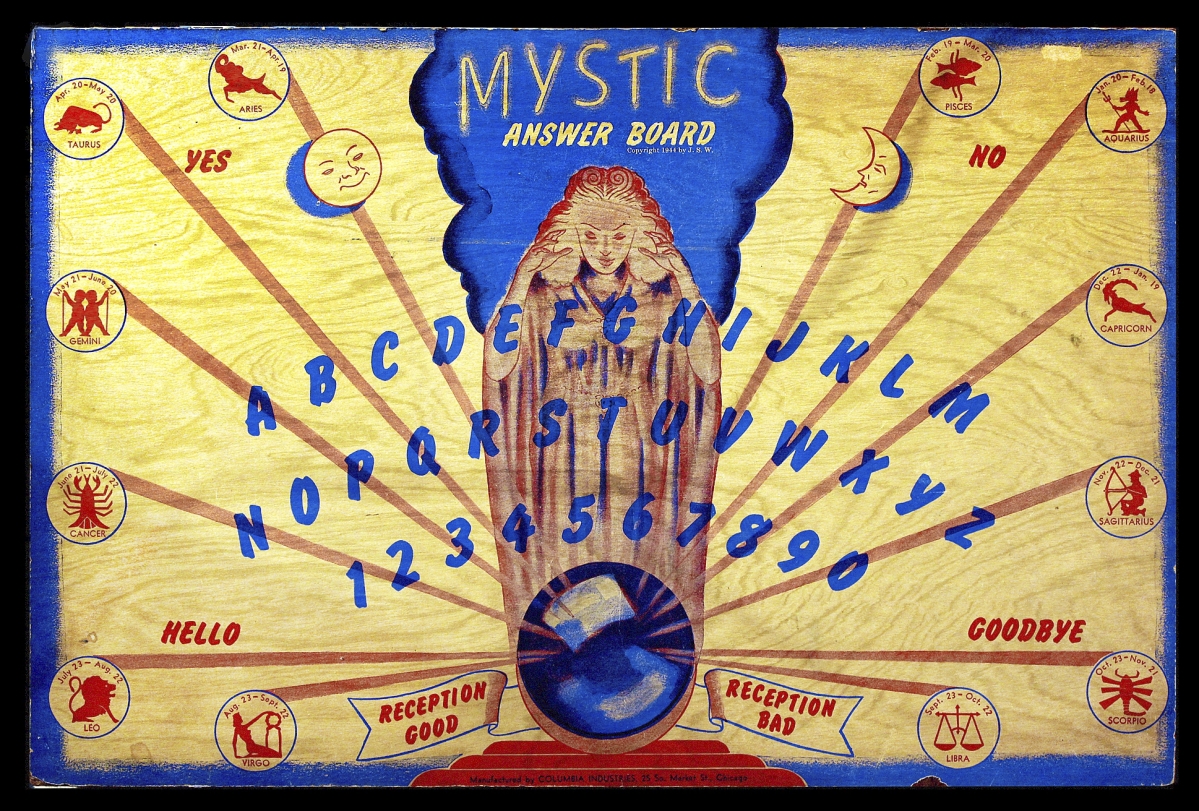

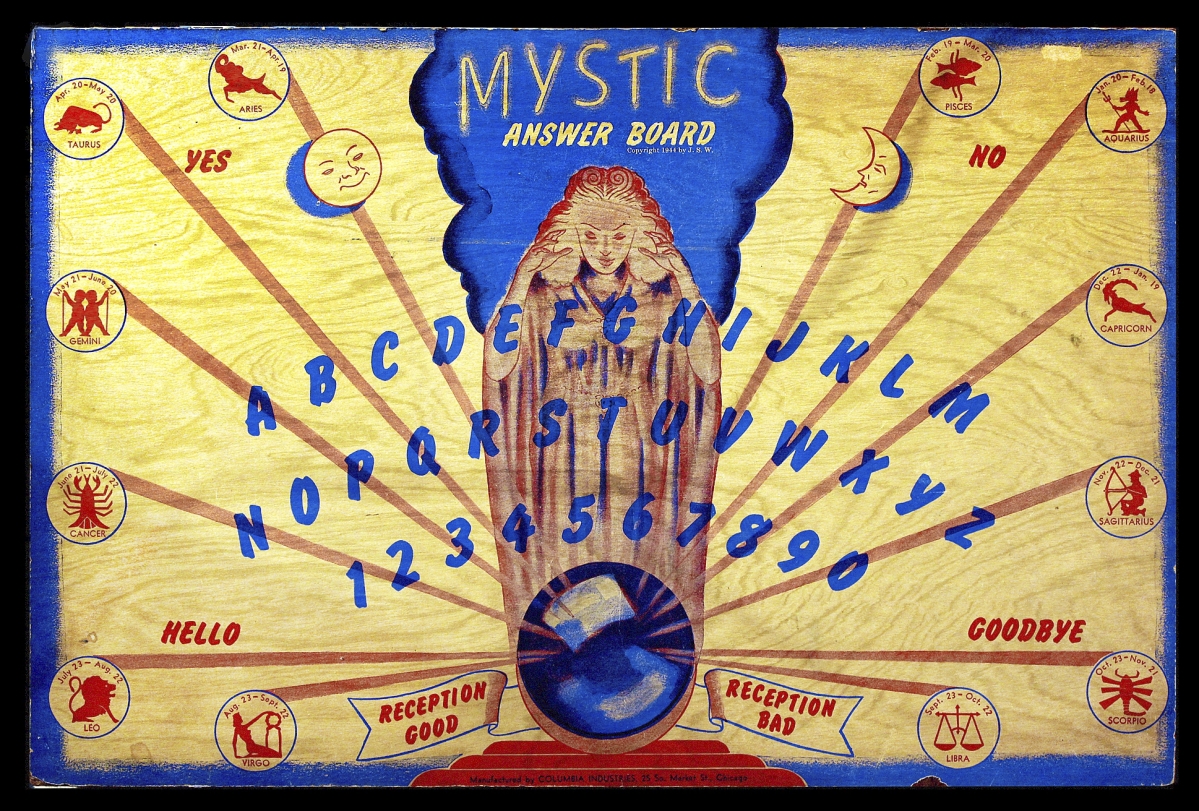

Mystic Answer Board from Columbia Industries, circa 1940s. Wood, pigments. Collection of Brandon Hodge. Photo Brandon Hodge/MysteriousPlanchette.com.

The fear of what is not there, the implied, the empty, the attempts to fill the emptiness, especially the voids grief leaves, permeate the exhibition. Gertrude Abercrombie’s “Search for Rest” and Morris Kantor’s “Haunted House” speak for themselves, but Iowa surrealist Marvin Cone’s 1938 painting, “Anniversary,” epitomizes this notion. The actual presence of the ghost at left renders the work quite harmless. Cone himself would note this, and in other works he would paint the shadowed steps and odd-angled rooms – with, occasionally, a cat – putting the ghosts in by leaving them out, letting our imaginations serve as mediums, peopling the absences with memories, shapes, sounds. Surrealism, of course, trades in Spiritualism, though it seeks to excavate spirits within rather than without.

Cozzolino sums up the issues for art history while speaking of orbs in one of Ivan Albright’s paintings, “the field has devalued realist methods for revealing the intangible. What if those chromatic haloes and lights were really there? Perhaps they were not before the eyes, but in the body, working through the body? We need a new methodology of realism that acknowledges that, for some artists, five senses were just a starting point. Conveying a somatic feeling of paranormal experiences through heightened visibility is a thread that needs attention in the history of this imagery.”

I wrote at the outset that I have never experienced the paranormal, yet one moment does rise in my memory. My mom was my Cub Scouts den mother for a time. You could hardly deem her a typical den mother timber since she saw us as a captive group of subjects for experiments in child psychology rather than as young men in need of woodsmanship skills. One afternoon, she brought out a green Melmac tray. A gold cloth covered it. We Cub Scouts, all around 10 years old, with our yellow kerchiefs tied around our necks, imagined what wonders were poking and pressing against the cloth. She set the tray down on our dining room table. We gathered around. She gave us paper and pencils. Then she said, “There are objects on this tray. I’m going to lift the cloth and leave it off for 30 seconds. Then I’m going to cover it again. Draw what you see.” Like magic, the cover came off. We were dead silent, taking in blocks, salt shakers, figurines, forks, toy soldiers: a cramped, motley assemblage. And then she covered it again. “Remember,” she said. “Draw, boys.” And so we drew. But what each of us drew was so strange, and the drawings were so unlike one another and so unlike what was actually on the tray when she finally showed us, that the exercise was unnerving. The whole experience felt conjured. All of us, I would wager, knew, from that day forward, that no one sees the world, or any moment of it, in quite the same way as anyone else. Perception cannot be trusted. My mother, the den mother, didn’t say that to her Wolf cubs. We knew. “We” may not be alone in the universe, but I am and you are. Art bridges. Art connects. Art is fearless. That’s a message. You decide where it comes from.

The Toledo Museum of Art is at 2445 Monroe Street. For information, www.toledomuseum.org or 419-255-8000.