The museum installed a photo collage of The Berlin 202, and here a viewer looks at the snapshots of the many portraits, landscapes and other paintings. Image courtesy Cincinnati Museum of Art.

By James D Balestrieri

CINCINNATI, OHIO – While preparing to write this story on “The Berlin Masterpieces in America: Paintings, Politics, and the Monuments Men,” the new exhibition opening at the Cincinnati Art Museum, I decided I would rewatch The Monuments Men, Hollywood’s star-studded take on the art historians, curators and designers who were sent to Europe as part of the Allied push after D-Day to seek out and salvage the cultural patrimony of the Western World, a patrimony Adolf Hitler thought was his to seize, display or destroy as he saw fit. It really is a star-studded film: George Clooney, Matt Damon, Bill Murray, Cate Blanchett – to name only four. Part Dirty Dozen, part Guns of Navarone, Clooney does his best Gregory Peck impression and the film ticks all the boxes: courage, a sense of mission, reverence and redemption, humor, pathos, tragedy.

And yet, as the Cincinnati Art Museum exhibition makes clear, it’s too much story to contain in two hours. There weren’t a dozen Monuments Men – there were hundreds. And their story doesn’t end when the war – and the movie – ends. In fact, the story of the Monuments Men and their legacy doesn’t fully begin until the war ends and hasn’t ended at all. In any world where a deep love of art and a sense of justice offsets imperious rapacity, the story of the Monuments Men should never reach its end. Even Netflix couldn’t do it justice.

From primordial times, when gold, precious stones, horses, cattle – and people – were prized plunder, from the Trojan Wars to the sackings of Jerusalem – more than once – and Byzantium – more than once – from Alexander the Great to Genghis Khan to Napoleon, from the looting of colonial Africa, Asia and the Americas to the despoiling of ancient Palmyra and Baghdad in recent years, art has been treasure. Treasure is the spoils of war. And, as the saying goes – to the victors go the spoils.

“An Artist Studying from Nature” by Claude Lorrain (French, active in Italy, 1604-1682), 1639. Oil on canvas. Cincinnati Art Museum, gift of Mary Hanna.

Monuments Men – and Women, for there were many women involved in the projects – rewrote these ancient rules of war, making restitution of property to their rightful owners an aspect of the morality of victory, making our cultural patrimony something worth fighting for and something worth restoring, even to our enemies, as we encourage them to remember their better angels and find ways back to the community of nations.

“The Berlin Masterpieces in America: Paintings, Politics, and the Monuments Men” centers on Cincinnati architect Walter Farmer, after he “applied to join the Monuments, Fine Arts and Archives (MFAA) branch of the Army. Farmer sought out this transfer, hoping it would be, in his words, ‘a kind of personal redemption…an opportunity to work for something I believed in,’ to assuage the horror he felt in the previous months, witnessing the destruction of cultural patrimony across Europe – the ‘carelessness and even viciousness the troops, ours and theirs, [exhibited] when confronted with beautiful objects and when quartered in wonderful historic surroundings.'”

In 1945, Farmer was placed in charge of the Wiesbaden Collection Point. Farmer worked with Renate Hobkirk, a German national he hired as a translator who would become his administrative assistant and, eventually his wife. After their divorce in 1966, Farmer began what would become a lifelong committed relationship with Ted Gantz. Margaret Planton, Farmer’s daughter with Hobkirk, and Gantz, are interviewed in the exhibition; their insights form the core of the story.

Installation image, “The Berlin Masterpieces In America: Paintings, Politics, And The Monuments Men.” Image courtesy Cincinnati Museum of Art.

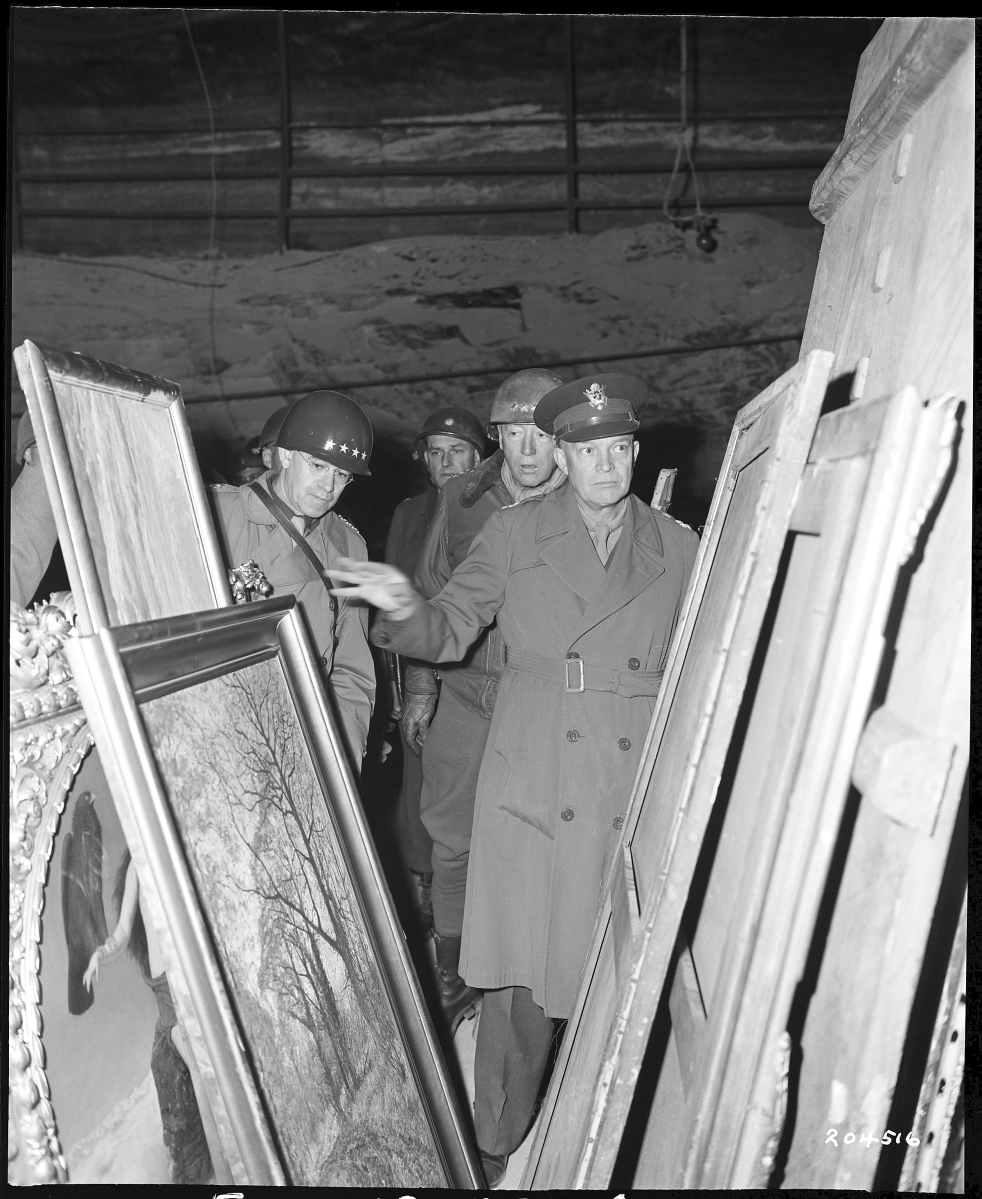

Wiesbaden was the collection point for works recovered from the salt mines in the German town of Merkers. A number of these works had been moved there from the Berlin State Museums by the Germans. As Farmer worked tirelessly to build a facility suitable for those and thousands of other artworks and to establish good relations with German art historians and curators, he received an order by telegram on November 6, 1945 to prepare 202 artworks for transport by ship to the United States “for safekeeping.” Farmer knew what this meant. Class A and Class B objects were those stolen by the Germans from public and private collections in occupied territories. Class C objects – the “202” among them – were German state property. The United States Army and Government intended to take and keep the “202” as spoils of war.

Farmer alerted his Monuments Men colleagues, and together they wrote a manifesto which stated, in part: “We are unanimously agreed that the transportation of these works of art, undertaken by the United States Army, upon direction from the highest national authority, establishes a precedent which is neither morally tenable nor trustworthy…We wish to state that from our own knowledge, no historical grievance will rankle so long, or be the cause of so much justified bitterness, as the removal, for any reason, of a part of the heritage of any nation, even if that heritage may be interpreted as a prize of war.”

The manifesto did not achieve its immediate goals. Indeed, it was not seen in the highest echelons. But it did set a tone. The “202” made the journey to the United States.

Botticelli, Mantegna, Watteau, Titian, Rubens, Brueghel, Vermeer: these are just some of the names of artists whose masterworks went on a triumphant tour – think triumph in the Caesarian sense – of museums in the United States from 1945 to 1949. After that, they traveled through Western Europe until 1952. In 1956, they were gathered in a museum in West Berlin. They would not return to their original home in Berlin until after reunification in 1998.

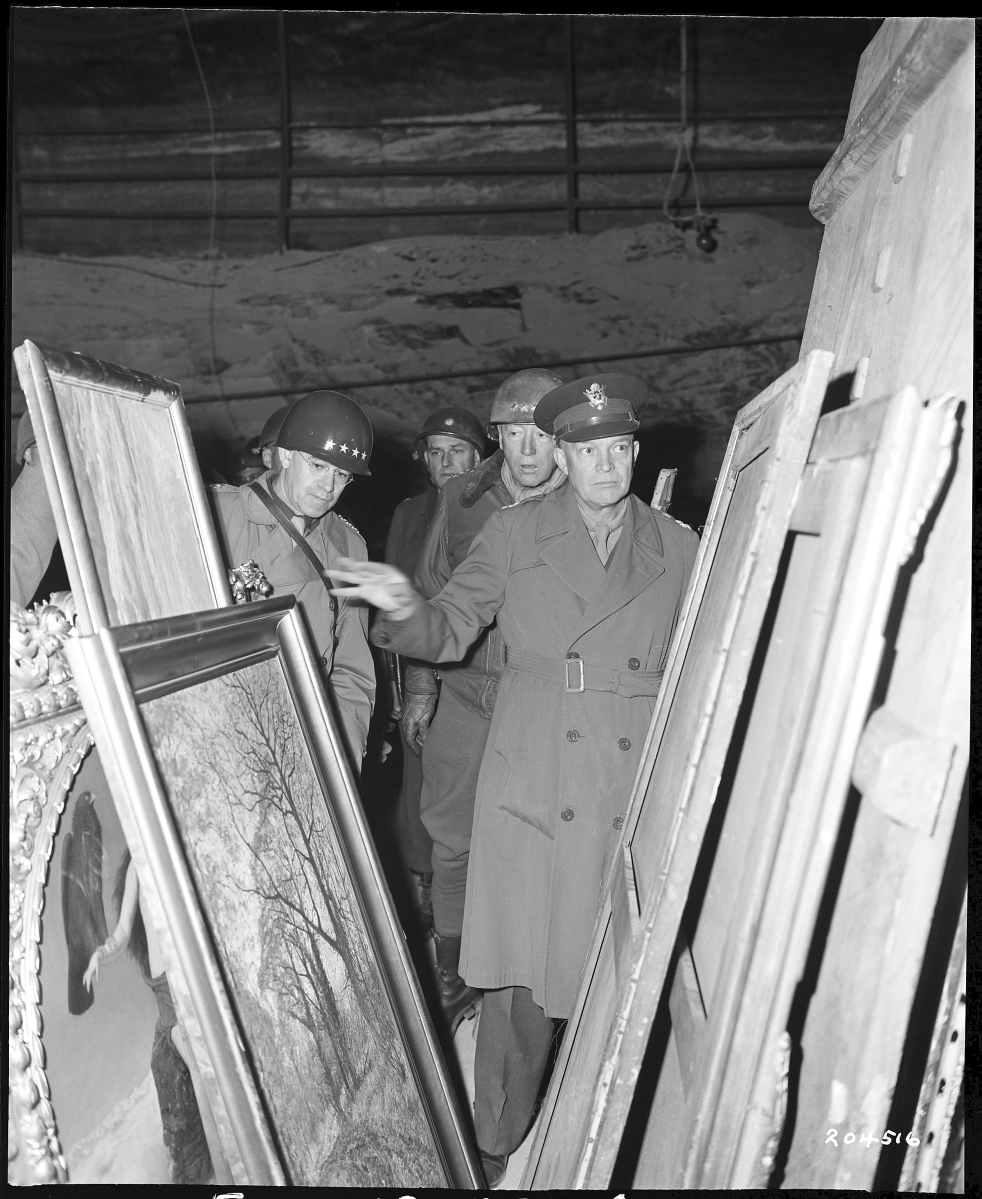

Generals Dwight D. Eisenhower, Omar N. Bradley and George S. Patton inspect art found in the Merkers salt mine, April 12, 1945. Image courtesy of National Archives at College Park, Md.

At the same time, the emphasis on restoring artworks to their rightful owners, especially Jewish collectors whose works had been seized by the Nazis, changes the course of art historical research. Provenance, authenticity, the study of the marks on the backs of paintings, records of restoration, ultraviolet and chemical analysis, photographs – not just of artworks, but of people where an artwork might lurk in the background – all these and more have refined art history even as they have reunited artworks with families and descendants of their owners. This has grown, and continues to grow, as the looted works of colonialism – the bronzes of Benin, the ceremonial objects and even the mummified and preserved bodies of Indigenous Peoples – leave museums and private collections and are sent home.

The exhibition rightly discusses the positive aspects of the American tour of the “202,” celebrated across the country and seen by millions. Saving European culture from Hitler and the Nazis came to be seen as one of the objects of the war. The idea of looting our enemies, transformed, through the Marshall Plan, into the idea of helping former enemies rebuild. Events such as the tour of the “202” facilitated this transformation. Of course, when our former ally, the Soviet Union, quickly became our Cold War foe, this idea became more appealing. But culture, and cultural exchange, helped keep the Cold War from heating up.

Museums exist to do two things: to be time machines and to be empathy machines. Art exists for those same reasons – I would add imagination machine as a third vertex. But if the single, unique, perceiver doesn’t connect with the single, unique object; if the work doesn’t transport the viewer back to a state of empathy with the impulse that gave rise to the work’s creation, nothing else matters. The artworks – in fact, all the objects that comprise our human cultural patrimony – are indifferent. Art doesn’t care whether it’s in a museum or a salt mine in Germany or blasted to atoms in a bombardment. Art doesn’t care about armies, or museum boards, or curators, or collectors. Art doesn’t care about the art market – whether it brings a hundred million dollars at auction or languishes unloved in an attic. Art doesn’t care whether you think it’s good or bad. Art doesn’t even care about the artist.

Viewers look through a selection of the storied 202 masterworks that were paraded around the United States following the Allied victory. Image courtesy Cincinnati Museum of Art.

If you’ve ever tried to make art – and, as I have argued in these pages for years, we are all always making art, to perceive is to make art – you know, instinctively, that what I have just said is true. If you’re reading this and trying to make sense of it, you are, in a very real way, making art. The difference between you and the Van Gogh who saw swirls in the night sky, or you and the anonymous woman who decorated a Hopi pot in the Fourteenth Century with her version of the swirling universe, is that you’re making it where it can’t be seen. Creation is a pushing away, a making that separates the self from something that is not the self. In this, art intersects with science: it is open-ended, a question that only leads to deeper questions, and it doesn’t care whether you believe in it or not. That there are those who do care in spite of these truths is the real subject of “The Berlin Masterpieces in America: Paintings, Politics, and the Monuments Men.” Their achievement is the addition of justice to art and a sense that art belongs not to any one individual or group of individuals, but to the world and to our shared posterity. In fact, I would argue that what the Monuments Men and Women did in separating covetousness from caring and caretaking was, in and of itself, a selflessly creative and artistic act.

The Cincinnati Art Museum is at 953 Eden Park Drive. For information, 513-721-2787 or www.cincinnatiartmuseum.org.