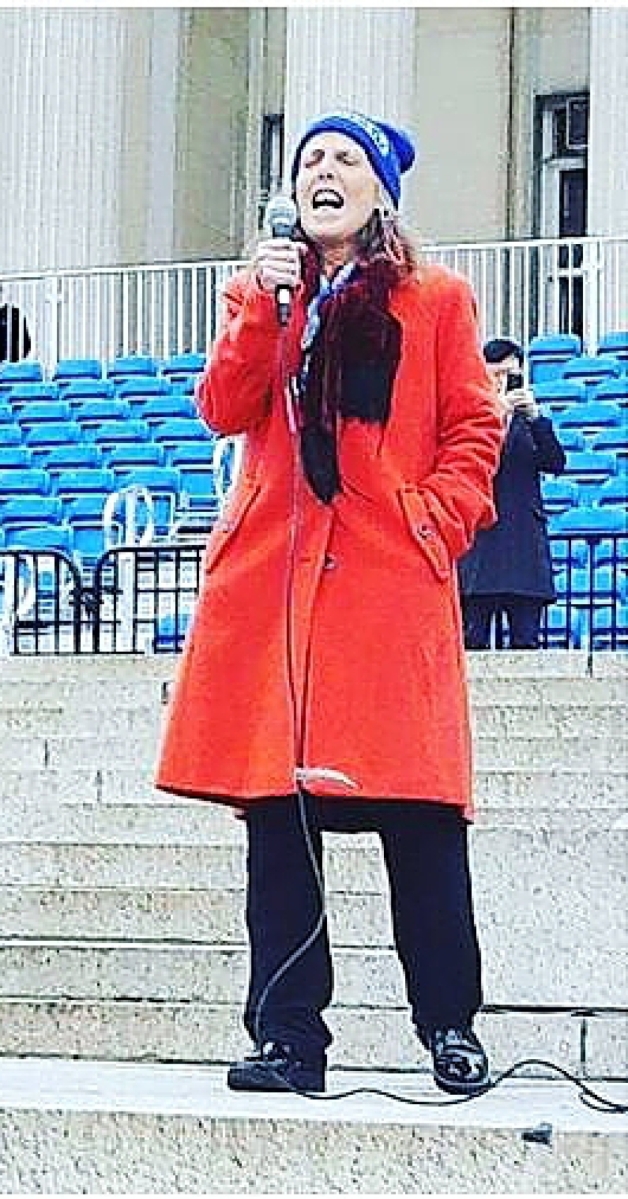

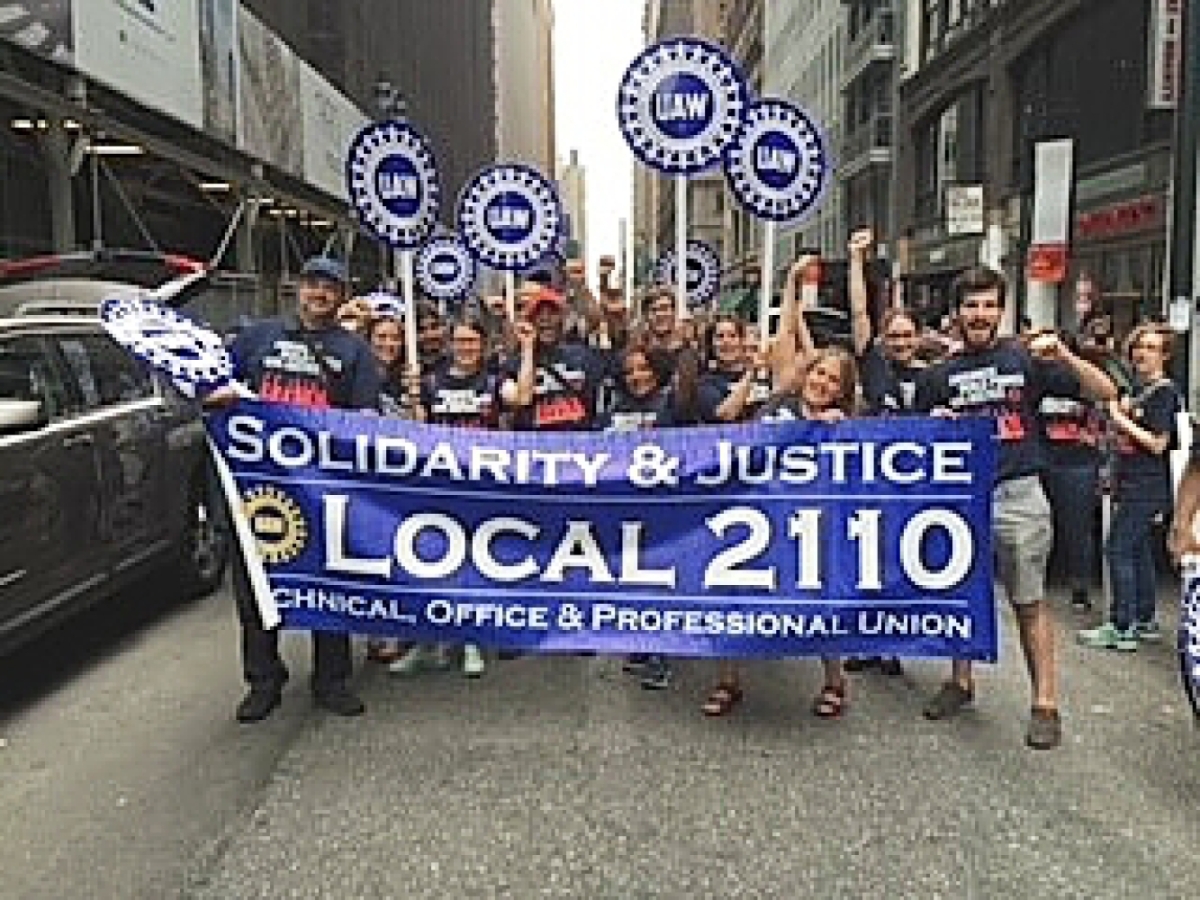

Bargaining Power. It’s a phrase you probably won’t see in any US museum’s mission statement. A wave of organizing that began about two and a half years ago, however, has led museum employees to form unions at institutions across the United States, including the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, New-York Historical Society and others. Maida Rosenstein, president of the United Auto Workers (UAW) Local 2110, has helped make headlines around the East Coast’s prestigious cultural institutions, most recently adding the Portland Museum of Art, MASS MoCA, the Whitney Museum, Brooklyn Museum as well as an effort to organize the workplace at the Guggenheim. We sat down with Rosenstein to get her view on the white collar union trend and assess the general resurgence of collective bargaining, long in decline since the 1960s.

Why are the institutional unionizing efforts becoming more commonplace? Does it relate to the broader economy or is it more specific to the museum field?

In part, I think it’s because there’s been a lot of expansion in museums and cultural institutions. The number of staff has increased, the number of institutions has increased. What I’ve noticed is that a number of years ago, our union represented people at the Museum of Modern Art and also the New-York Historical Society for years – but there wasn’t any real new organizing among museums until a few years ago when there began to be a generational change. This younger generation has noticed the pay gap. The boards of these museums and the leadership are highly paid. A lot of institutions have gone through big building expansions for which they’ve raised millions of dollars. And yet the staff has remained very low paid.

Has the staffing profile changed?

It used to be said that you couldn’t work at a museum unless you were a “trust fund baby,” because no one could afford to work at a museum. That is not working for this generation of workers at all. Even though people take these jobs because they want to work in a museum, because they love the arts, they also need to support themselves and have sustainable work. The pay is really low, even for full-time professional people, and you’re supposed to expect very low pay. Museums also rely on people whose labor is very precarious, people who are part-time, seasonal workers.

To clarify, are you referring to art handlers and workers more on the logistical side of operations?

Not just that, people who are in front-facing positions like visitor services or in retail and security. They often are low paid, part-time workers with no or very few benefits. And jobs like art handlers and museum educators face intermittent or casual labor, so even where they’re being paid a little more, people are working intermittently and having to work multiple jobs. When you see your institution raising millions of dollars for a building expansion and yet there’s no money for staff or benefits, that’s an issue.

So the inequality is built in?

Exactly, you have a museum director who will make close to a million dollars, then you have a full-time curator who will make $70,000, a curatorial assistant will make $38,000. It’s a very big issue.

Is the pandemic contributing to the push for unions in museums? For much of 2020, a majority of institutions were shuttered, with many employees furloughed or laid off.

I think the pandemic has exacerbated the situation. It was made very clear that staff had no voice, no control over what was going to happen. Institutions closed down, they laid people off, they furloughed people and made decisions without any accountability to staff. Now that people are coming back, there are health and safety issues.

If these needs aren’t being met, how will unionizing help meet them?

Well, the main thing about a union is that it gives you a right to bargain with your employer over terms and conditions of employment, and collectively you have some power and some voice over these things. Unionized workers have more power and more leverage and are able to do better. At MoMA we’ve had a union for a long time and people have been able to negotiate some significant improvements through unionization.

For example, their wages are higher and they’re able to protect their benefits. During the Covid pandemic, no unionized worker was laid off or furloughed, including front-facing staff who could not work because the museum was shut down.

Are some museum unionizing efforts more unique than others, and what specific hurdles are unique to some?

Well, if you’re working for a museum in Alabama, I’m sure the actual work is very similar. But you’re in Alabama. Under American labor law, you still have to unionize workplace by workplace, and at every one, the issues can be a little bit different.

How do current museum working conditions relate to historic conditions of the 1950s-2000s?

I think there’s a real generational change in viewpoint of unions. When I first came into the labor market, I was a university worker and unions were very rare, much rarer among office workers or administrative staff. They were considered mainly to be for blue collar workers. This generation is much more pro-union and work has changed as well. They’re more progressive, far more likely to say, ‘We need to change the workplace.’ They believe the museums need to be more responsive and accountable to the community at large. Some museums – to their credit – are trying to implement changes.

Most recently, your local was involved in filing a petition with the NLRB asking for it to authorize a vote by employees at the Guggenheim. What employees would be represented and what do you think the prospects are?

It’s about 160 people that we think are in the unit. I’m very optimistic, but obviously it’s up to the people who are voting.

How do you respond to the sentiment by some museum officials that unionizing would inject divisiveness “on a daily basis” into the institution?

I think that only if employers are opposing unionization do you create divisiveness. It’s the employer who’s creating it in that case by opposing unionization, which they really should stay out of because employees have a right to organize. On the contrary, having a union means that you have an organization where you can democratically make decisions. It’s like saying democracy creates divisiveness.

–W.A. Demers