By James D. Balestrieri

SCOTTSDALE, ARIZ. – Unwitting players enter every life. They open us to possibilities, creating the apertures we peer through and then step through as we pass from past to future. In the lives of artists, the roles these unwitting players play, from hindsight and the vantage of history, are often pivotal.

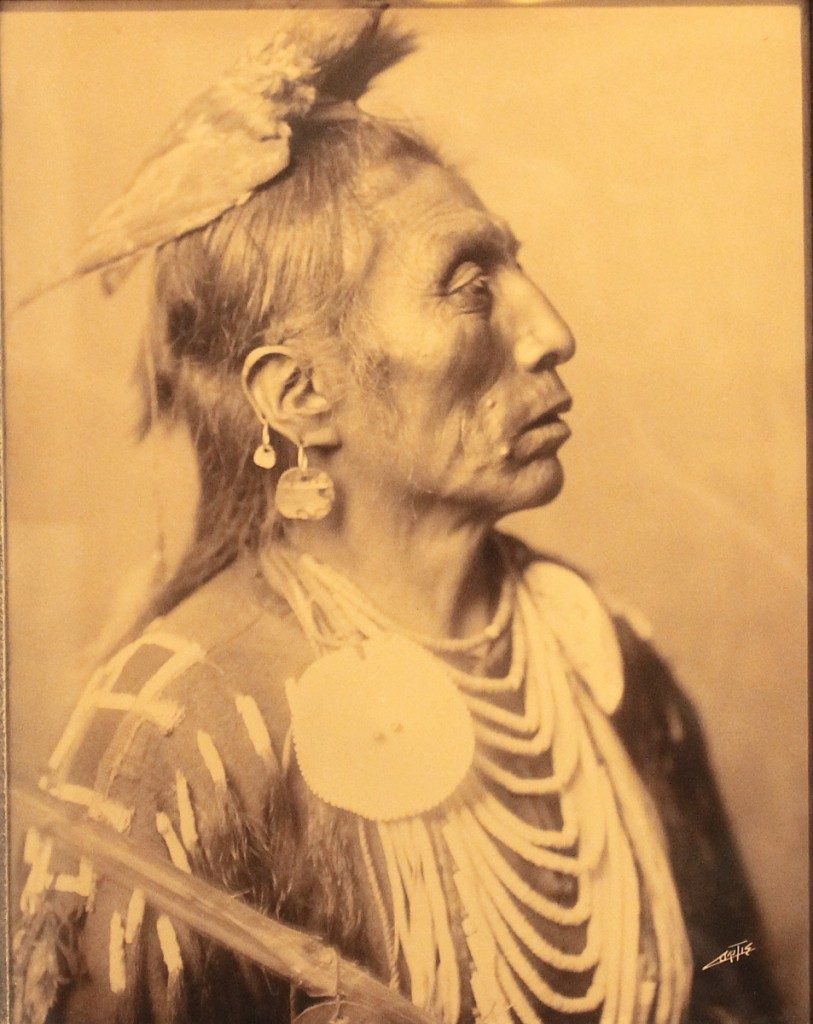

“Light and Legacy: The Art and Techniques of Edward S. Curtis,” the new exhibition at Western Spirit: Scottsdale’s Museum of the West, takes a comprehensive look at one of the seminal chroniclers of the Indigenous Peoples of the American West. Curtis’ 30-year odyssey took him from Arizona to the High Arctic and from the Mississippi River to California. He visited more than 80 tribes, took tens of thousands of photographs, recorded thousands of languages, songs and stories on wax cylinders, and shot some of the first films of Native Peoples. His passion and artistry are undeniable and yet, as Curtis scholar Mick Gidley writes, “The nature of ethnographic investigation and, especially, writing has been a matter of much heated theoretical debate. We have to accept that, in a variety of ways, anthropology does not simply record Indigenous people; it constructs them.”

Curtis was inspired by the academic currency of what has come to be known as the “Vanishing Race” myth at the turn of the Nineteenth Century to the Twentieth. Long before Curtis came along, “Manifest Destiny” had decreed that progress in the United States was white, male and Anglo-Saxon in origin. Native Americans and their culture were thus seen as too fragile and primitive to survive prolonged contact with the expansion of Western civilization into the American West. Natives were doomed to literal extinction or to seeing their traditions subsumed and erased into the new, dominant culture. Recording them before they and their lifeways vanished could be a life’s work. Edward Curtis saw an opening here, an aperture, and stepped through it. The result, the lavish 20 volumes of The North American Indian, would consume him. Apertures close as well as open, and, in an ironic twist, it was Curtis, his art and his way of life, that would almost vanish into oblivion.

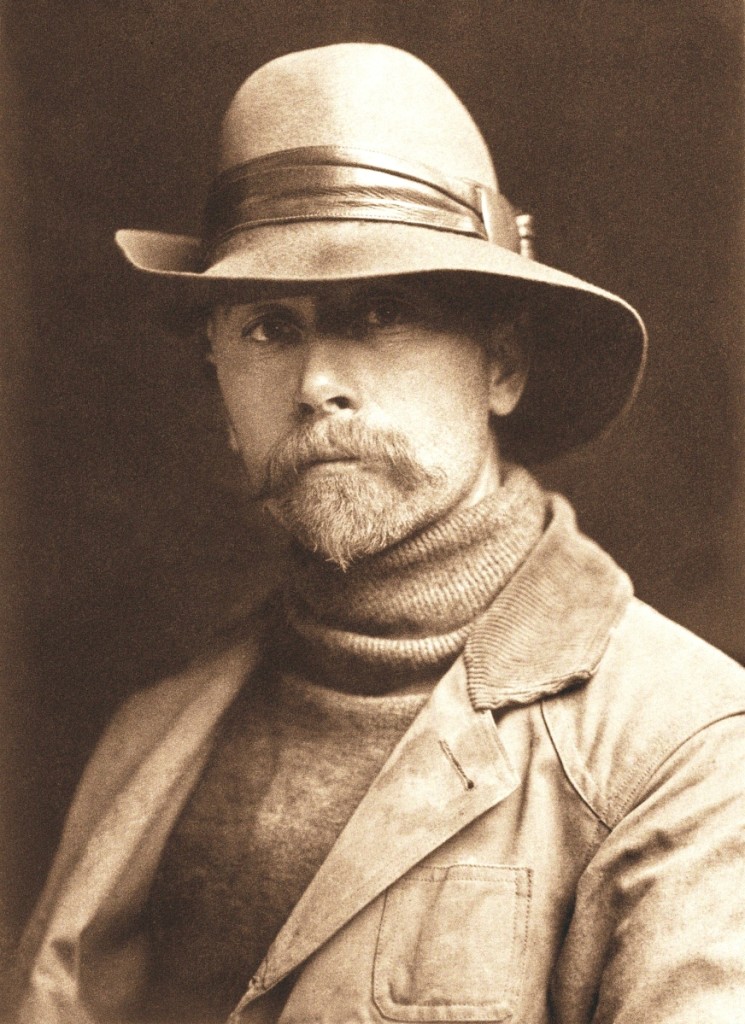

The camera lay in wait for Curtis. You might say that the camera chose him. Curtis’ father, Johnson, a Civil War vet who today would almost certainly be diagnosed with PTSD, returned from the war with two things: a passion to spread the teachings of the Bible and a stereographic lens. In Whitewater, Wisc., where Edward Curtis was born in 1868, and in Minnesota, where the family moved when he was a boy, poverty reigned. Curtis accompanied his father on canoe trips deep into what Laura Ingalls Wilder referred to as the Big Woods. It is there that young Edward almost certainly encountered Native Americans for the first time.

But that lens. That lens was the first aperture, the first opening onto Edward Curtis’ future. It called out to him as a thing that could serve to help him break free – in his imagination if not in reality – of the despair that plagued his family. So he built a camera, his first, with that lens and a box he made of wood. Soon after, he found work with a photographer in Minnesota. Where Curtis’ father picked up that lens and why he lugged it home from the Civil War are lost to time. Imagining it through the stereoptic lenses of Edward Curtis’ eyes is, perhaps, all we really need to see.

In 1887, Johnson Curtis moved the family to Port Orchard, Wash., – where his failing health would soon fail him altogether. Edward worked at whatever he could to support the family, including clam digging and cutting firewood. One day, Curtis fell off a log, twisting his spine. The injury would render him an invalid for some time. A neighbor, Clara Phillips, would help tend to Curtis. But Clara is no unwitting player. Clara would marry Curtis and play a major role in his rise and fall.

The next purveyor of apertures has no name. He enters the tale for a moment and moves on. In Timothy Egan’s biography of Curtis, Short Nights of the Shadow Catcher, the cinematic moment runs thus: “Clara visited one day and found Edward sitting up, enraptured by a contraption on the kitchen table: a 14-by-17-inch view camera, capable of holding a slice of life on a large-format glass-plate negative with such clarity it made people gasp. The camera was not cheap, the price much derided by Edward’s mother. He had bought it from a traveler looking to raise a stake on the way to the goldfields.”

Who was that mysterious traveler? He is lost to history, but he and his lust for gold and his camera opened another aperture. Curtis saw a way out – and in. He borrowed $150 against the family property, moved to Seattle – a boom town – where he partnered with an established photographer and soon opened his own studio. Curtis was tireless behind the camera and in the darkroom and his portraits: likenesses of brides, debutantes and moneyed men – as well as the odd artistic nude – made him a toast of the town.

Edward Curtis would have been set for life.

In 1896, however, Curtis took note of Seattle’s most famous figure: Princess Angeline, the last daughter of Chief Seattle, an old woman who lived in a shack on the bay, digging shellfish and selling them to scrape by. Curtis’ portrait of the ancient, time-lined Angeline, and the photos he took of her as she dug for clams, silhouetted against the sea and sky, opened a new aperture for the budding photographer, the aperture that would set the course of the rest of his life. Angeline, who passed away later that year, would never know, or profit from, the influence she exerted on Curtis.

Installation image, “Light and Legacy: The Art and Techniques of Edward S. Curtis” at the Western Spirit: Scottsdale’s Museum of the West through April 8, 2023.

Yet another unwitting aperture opened in the form of the magazines that featured the work of the Photo Secessionists in New York – Alfred Stieglitz, Edward Steichen, and others – who sought to elevate photography to an artform that would rival painting. Curtis would seize on their manipulations of light and techniques in the darkroom and employ them throughout The North American Indian. These shadows and softnesses and the overall somberness of his subjects would irritate anthropologists and contribute to popular, romanticized notions of Natives as stoic, tragic people whose time was passing. But Curtis meant to graft art onto ethnography and let viewers see into the souls of those who sat for him and the worlds they inhabited. The sheer volume of his work and the vitality of the peoples he photographed betrayed the “Vanishing Race” theory and his own opinions on their destinies would evolve over time.

A chance meeting with George Bird Grinnell – Curtis saved him and a lost party of naturalist luminaries on the slopes of Mount Rainier – led to an invitation to join the Harriman Expedition to Alaska and a trip to Blackfoot country in 1900 to witness the then-forbidden Sun Dance. Grinnell was not an unwitting player though he did open a very wide aperture. He introduced Curtis to the “Vanishing Race” theory and planted the notion of a race against time and inevitability that would become the passion of The North American Indian.

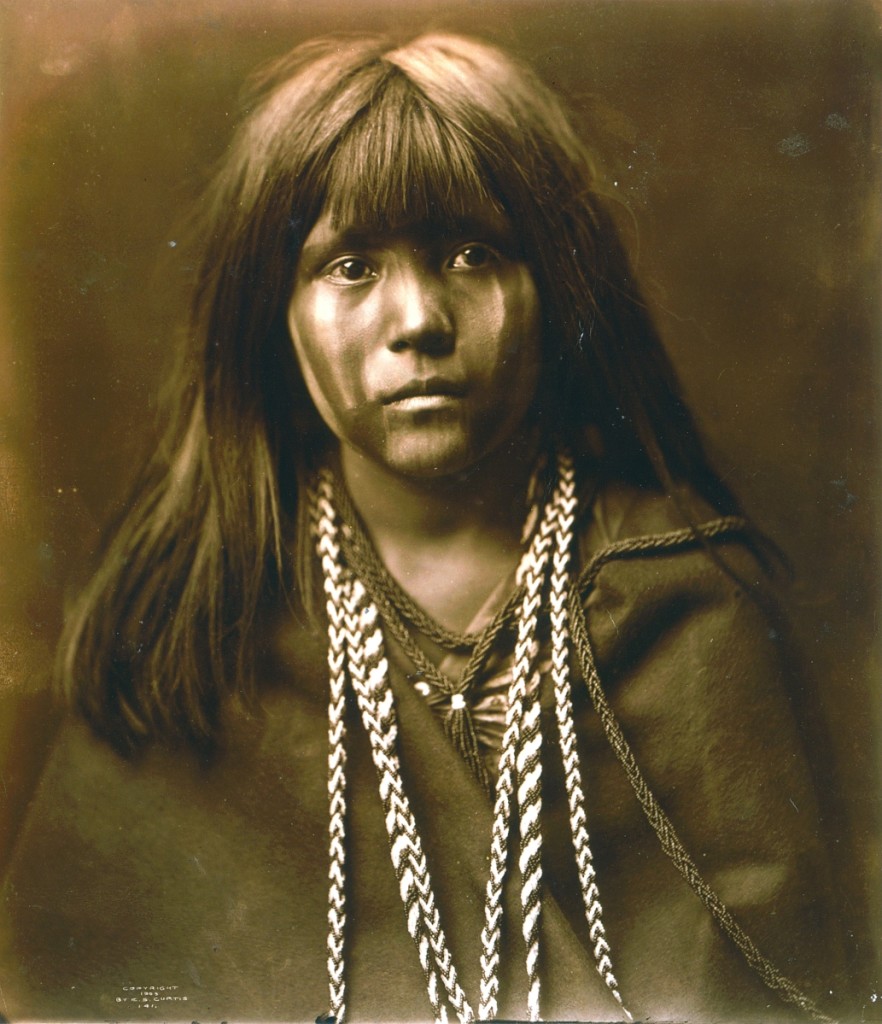

After Montana, Curtis turned to the Southwest, to the Navajo and Apache, wanting to have something to show when he headed east in search of funding for the grand endeavor. In 1903 he found himself among the Mojave People. While there, he photographed an adolescent girl named Mosa. Three years later, in New York, after meeting and impressing Theodore Roosevelt – then the president – Curtis obtained an audience with J.P Morgan. At first, Morgan rebuffed Curtis, but when Curtis placed the image of Mosa before the world’s wealthiest man, Morgan’s tone changed and he is said to have conceded, “I will lend financial assistance for the publication of a set of books illustrated with photographs such as these.” Mosa looked back at J.P. Morgan, her otherness falling away to frankness, melting into the mystery of shared humanity with all the power and beauty of the “Mona Lisa.” Perhaps the most important of those “unwitting apertures” who propelled Curtis’ dream, Mosa still looks back at us, her gaze undimmed by time.

Curtis would fund his project but fail to make provisions for his family. For the next 20 years he would often be away from home for months at a time. He would sacrifice his thriving studio, marriage, health and, ultimately, the rights to his decades of labor. His adherence to the “Vanishing Race” theory would evolve into an angry realization that government policies were formulated to ensure that the theory would be a fait accompli. Still dreaming of future adventures, Curtis would pass away in obscurity in 1952. In the 1970s, in a storage space owned by the Lauriat bookstore in Boston, hundreds of thousands of Curtis’ prints would come to light at a time when Native Americans were beginning to revive their heritage and assert their rights. Curtis has been revered and reviled ever since, but his images continue to haunt. They are occasions for essential discussions and the growing number of Curtis exhibitions and the increasing value of his work at auction shows that they aren’t going away.

Those Curtis photographed are the sine qua non of unwitting players in Edward Curtis’ life, career, art and lasting legacy. Their images are apertures – for us – into individuals who might otherwise have vanished, not into racial oblivion, but into anonymity.

If time has retrieved Edward Curtis from oblivion, it has not retrieved his way of life, the hyphenated life of the artist/adventurer, scholar/adventurer, naturalist/adventurer. Curtis was one of the last of his kind – Roy Chapman Andrews comes to mind perhaps as a kindred soul in paleontology and anthropology. Peter Beard’s photographic/ethnographic adventures in Africa and Jacques Cousteau’s undersea work partake of something of this spirit perhaps. Yet adventure is a way of life we long for as a species. Curtis and Andrews inspire Indiana Jones who skirts, not always successfully – I’m looking at you, Temple of Doom – the “White Savior” complex and the moment when archaeology is just looting while at the same time enkindling a nostalgic yearning for a life that combines scholarly erudition with righteous derring-do. Outer space emerges as the last, largest and most inexhaustible aperture, but success there depends on science as opposed to seat-of-your-pants, skin-of-your-teeth passion and cinematic improvisation.

What does it say about a person like Curtis who wants to be among people who are not at all like him? What is the psychology of the artist/adventurer, of adventurers in general? What drives them, fulfills them? What’s missing in their lives?

Did Curtis want fame, wealth, respect? To be seen as an artist? Scientist? Anthropologist? Impresario? Savior? All of the above? Or did he merely wish to be elsewhere, occupied in a grand enterprise and adventure, whatever the outcome? The smallness of the world makes the aperture of adventure seem to narrow and iris in. Despite his stumbles, failings and fate, I envy the sweep of Curtis’ ambition and aspiration and take comfort in the last words of Paul Zweig’s masterful book The Adventurer: The Fate of Adventure in the Western World: “The world may or may not harbor spacious possibilities, but the adventurer’s magnificence lies in the going itself.”

Co-curated by Dr Tricia Loscher, assistant director for collections, exhibitions and research at Scottsdale’s Museum of the West and Tim Peterson, Museum Trustee and collector, “Light and Legacy: The Art and Techniques of Edward S. Curtis” asks all these questions and more. Your answers to those questions, however, may well have more to do with the unwitting players who have opened apertures in your lives, and whether you have stepped through them or chosen other paths.

Newly open, the exhibition runs through April 30, 2023. The exhibition is made possible with generous sponsorship from The Peterson Family; The Virginia G. Piper Charitable Trust: Charles F., Jennifer E., and John U. Sands; Theodore “Ted” Stephan; Scottsdale Art Auction; True West Magazine: Ken Amorosano & Bob Boze Bell; and the City of Scottsdale and its Tourism Development Commission.

Western Spirit: Scottsdale’s Museum of the West is at 3830 North Marshall Way. For more information, 480-686-9539 or www.scottsdalemuseumwest.org.