The sale’s top lot was Bill Traylor’s untitled drawing at $182,500. The graphite and colored pencil work appeared on the back of a Phillip Morris advertisement, the silhouette itself a part of the composition. It dated to July 1939, around the time that Charles Shannon discovered the artist in Montgomery, Ala. It had provenance to artist and collector Elyse Saperstein, descending to her sister when she passed away.

Review by Greg Smith, Photos Courtesy Slotin Folk Art

BUFORD, GA.- Steve Slotin did another $1.5 million in his November 13-14 Self-Taught Art Masterpiece sale. The situation begs some clarity – the auctioneer’s Masterpiece sale last November grossed about the same number. At that time he told us, “This was by far one of our best sales in our 30 years of doing auctions,” and if we were to quote him again after this go-around, we’d sound like a broken record. He’s flying high.

There is no denying the thundering momentum that Southern Folk Art is experiencing in this moment.

“These artists were the fabric of America,” Slotin said. “At the time they didn’t get any attention. No recognition, representation or any help. But it does seem like things are turning, that these artists are getting recognized and I think people are responding extremely positively to what we’ve been offering. I think they love seeing this part of America. Over time, this will be thought of as the golden age of American art.”

Bill Traylor, Alabama’s patron saint of self-taught art, was behind the sale’s leading lot as his untitled work depicting a woman holding an umbrella went out at $182,500. The drawing had been featured in Jeffrey Wolf’s documentary Bill Traylor: Chasing Ghosts and came by descent from the collection of artist and collector Elyse Saperstein. Slotin sold Saperstein’s collection in the early 2000s, though this work passed to her sister, from where it was consigned.

The woman in blue skirt and striped blouse peers upward at her umbrella, a dog by her side and a geometric basket appearing almost unrelated in the top of the work. The graphite and colored pencil drawing appeared on the back of a cardstock advertisement for Phillip Morris cigarettes, the back lithographed with an image of a smiling boy in bellhop attire and white gloves holding a box of smokes. When viewing Traylor’s work, it appears within the form of the boy’s silhouette.

“Early on, when Bill Traylor was just starting to produce work, he was drawing on refuse, stuff out of the garbage,” Slotin said. It wasn’t until 1939 when artist Charles Shannon famously noticed the artist selling his works in front of a blacksmith shop on Monroe Street in Montgomery. This work, with a handwritten date of July 1939, is from the earliest known period of the artist’s three-year production.

“The interest was quiet before the sale but I think people recognized that it was gorgeous, being pure and simple and before he had any kind of supplies,” Slotin said. “It was created in the purest, truest form of creating art before anyone showed interest in his work.” Slotin said it sold to a private collector.

In any given sale with the auctioneer, returning buyers may recognize a familiar catchphrase that Slotin routinely uses: “The Strange, The Unusual, The Vanishing America!” The first two descriptors might characterize “Millenium #4,” a 1997 oil on canvas measuring 80 by 68 inches by Southwestern artist Fritz Scholder. It sold for $63,750. A major figure in Native American art, Scholder’s career can perhaps be divided between the Pop art portraits of his people and a dark, surrealistic abstraction that he found in his later years. The “Millenium” series is the latter, centering on abysses and dream-like figures like the centauride in the present work.

From Fritz Scholder’s “Millenium” series, this painting dated 1997 and numbered 4 would sell for $63,750. It was a good buy per square inch for the 80-inch-high work.

Another anomaly came in the form of Icelandic artist Oli Johannsson’s “You Can’t Come In,” a 2009 acrylic on canvas of 37 inches square. Johannsson was a self-taught artist that Slotin described as “a starburst.” He received his first show at London’s Opera Gallery in 2006 and passed away in 2011. Painted on the back of “You Can’t Come In” is an unfinished color plane image that bears the artist’s signature grid-like structure seen in much of his work, though the front is a more seamless figural image depicting the bucolic life of the artist’s homeland in Iceland. The work sold for $10,000.

Georgia is a beacon for self-taught art and the High Museum in Atlanta has established itself as a leading institution in the field. Katherine Jentleson, the curator of two concurrent exhibitions at the museum, “Gatecrashers: The Rise of the Self-Taught Artist in America” and “Really Free: The Radical Art of Nellie Mae Rowe,” was on hand during the auction’s preview exhibition to speak with collectors of self-taught art. Slotin described the collaboration with the museum as a win-win where like-minded collectors and curators can come together to talk about the field and the currents moving through it.

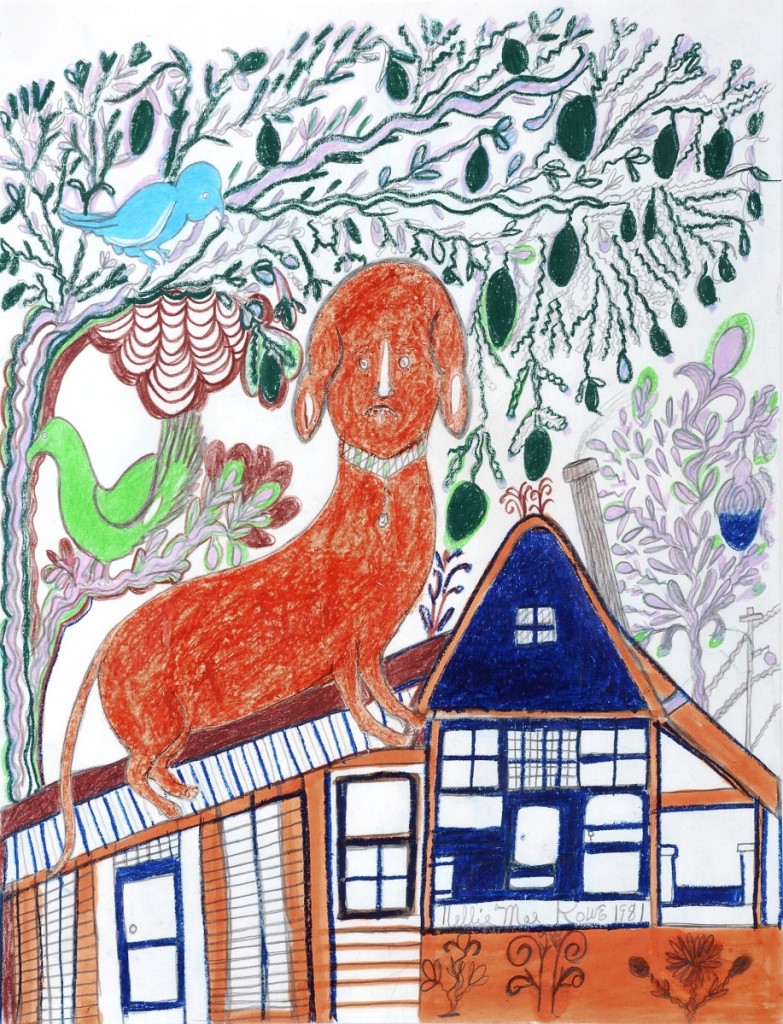

Rowe had five works in the sale as the top lot, “Dog on Roof With Birds,” established an auction record for the artist at $30,000. The work had provenance to the collection of Judith Alexander, the gallerist most credited with bringing the artist to recognition. The 1981 work was created with paint, crayon, colored pencil and graphite on paper and measured 23½ by 18 inches. Selling for $8,750 was an example of a type of work that originally piqued Alexander’s interest in the artist, a doll. In an August 2021 interview with Antiques and The Arts Weekly, Jentleson said that Rowe’s genesis as an artist began with dollmaking as a child. “She would take the dirty laundry laying around and transform them into dolls,” she said. “Her mom was a seamstress and quilter. There’s a couple different functions of them apart from harping back to her childhood – it was also a way to keep her company. She was living alone for the last 40 years of her life. Having these dolls, some of which were on the larger size and as big as a toddler, they were a kind of comfort to her. She made them in the image of herself and people she knew. She also called them her children, which was revealing, as she did not have children.” Rowe’s hand-stitched doll measured 24 inches high and came from the Chuck and Jan Rosenak collection.

An auction record for Nellie Mae Rowe was set at $30,000 with “Dog on Roof With Birds.” Just 35 miles down the road from the auction gallery is the High Museum of Art, where Rowe’s work currently hangs amid a retrospective exhibition. The paint, crayon, colored pencil and graphite on paper had provenance to Judith Alexander, and Slotin called it one of the artist’s masterpieces.

Three works appeared from Sam Doyle, led by an $11,875 result for “Miss Zero,” depicting a topless woman on one knee in the grass. The work was previously sold at Slotin in 2010 for $6,000. At the time, the catalog noted that Doyle was asked about the significance of the work’s name, to which he sharply replied, “Because she was worth less than her name.” Two works on paper by Doyle sold for less, the medium a more rarified format for the artist who more commonly painted on found tin. “Usually it’s a later work,” Slotin said of this type. “Paper was a little harder for him to display, he had a little gallery, The Shack, and he would often just lean the paintings on the shack. The two pieces in this sale were together, they were on the same subject.” Both told the story of the 1893 Sea Island Hurricane, a devastating storm that rocked South Carolina’s coast and killed 2,000 to 3,000 people. When the bridge to the island was swept away, boats became the only means to provide aid. Seen in Doyle’s “The Red Cross Boat Responding To the Sea Island Hurricane of 1893,” a watercolor and graphite work, is a scene of rescue as the townspeople stand on the shore with a paddlewheel boat in the process of arriving. The other watercolor, “Pine Hill Frogmore, SC After the Hurricane of 1893” is figureless, the image centering around downed and leafless trees with a house turned over in the background. Both works were consigned from the original Waynesboro, Ga., owner who purchased them directly from Doyle in the 1970s.

“Everyone knows Dave Drake now, and it has risen the prices on all pottery,” Slotin said. “It takes one great potter to bring awareness to all other potters.” The first day of sale was led off with 31 lots of Southern pottery, the Meaders family accounting for a little over a third of those. All were led by an early Smash face jug by Lanier Meaders at $6,250. Circa the 1960s, the jug features a thick matte green glaze and a rich tobacco spit atop the head. “It’s very early and primitive,” Slotin said. “In the early days he didn’t understand that you had to put wax over the eyeballs so that the glaze wouldn’t stick. Later on he learned a lot, but it shows a really early stage of his learning curve.” Slotin said the jug is more representative of the work of his father, Cheever, and was produced around the time that the Smithsonian created a documentary on the family, reviving the practice of the folk art. “Lanier is credited with almost singlehandedly saving Southern folk pottery,” the auctioneer said.

All prices reported include buyer’s premium. For information, www.slotinfolkart.com or 404-403-4244.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)