Advertisements such as this were used to attract hunters to the numerous hunting and sporting clubs. This club was located on an island off the coast of North Carolina. Hunters often returned year after year to their favorite clubs.

Review by Rick Russack, Photos Courtesy Guyette & Deeter

EASTON, MD. – A cigar store Indian with provenance back to 1874 earned more than a half-million dollars in a sale that saw three goose decoys each sell for more than $100,000 and about a dozen other items sell for more than $50,000 each. The November 11 sale, which included sporting art by some of the genre’s best-known artists, was particularly strong in Southern decoys, with birds from two major collections.

Several fish and other carvings by Oscar Peterson were offered, as were miniatures and decorative carvings by well-known craftsmen. The 375-page catalog of the sale is a reference work well worth owning, with extensive biographies of the collectors whose decoys were in this sale, extensive biographies and details concerning several of the decoy makers – much of it not previously published – plus informative articles on the “lore” of duck hunting, including a discussion of the firearms used by market gunners, information on the early sporting clubs, information on pigeon decoys and a discussion of Mason swan decoys as well as a discussion of hunting clubs. The live-streamed sale featured Jim Julia at the podium with bidding also available via three internet platforms, numerous phone lines were in use and absentee bids were accepted. With a gross of more than $4.6 million, it was another strong sale for Gary Guyette and Jon Deeter, and it was led by the cigar store Indian princess. The company has now sold more than $10 million worth of decoys in 2021.

It’s rare to know the “backstory” on pieces like this Indian princess, but the documentation for it goes back to the original owner, John Richard Rose, who opened a “lottery” store in Louisville, Ky., in 1874, according to auctioneer Jon Deeter. There is a vintage photograph showing the figure in front of the store, which was also selling cigars and tobacco. Rose’s granddaughter, as related in the catalog, said, “My grandfather came to Louisville from Chicago in 1874, opened the store, and purchased the Indian from where it stood outside another store…” The name of Rose’s business was changed in 1895 when his son entered the business. Therefore, the vintage photo has to have been taken between 1874 and 1895. In 1974, after 100 years in business, the store closed and the figure was sold to a local attorney, Joe Davis, for the sum of $5,000 as reported by a local newspaper. Another photo shows the Indian still outside the store when it closed. The princess wears a four-feather headdress, with red, green, yellow and blue paints, and a dress carved and painted in the same colors as the headdress. She holds a bundle of cigars in one hand and tobacco leaves in the other hand. The catalog speculates that the Indian may have been made by Samuel Robb or Thomas Brooks. Bidding was brisk, with three phone bidders competing with one in the room. In a creative bit of salesmanship, as Jim Julia was calling bids on the princess, Hank Williams’ “Kaw-Liga” was playing over the PA system. That classic country song tells the story of a wooden Indian who fell in love “with an Indian maid over in the antique store.” When bidding ended, one of the phone bidders was the winner, paying $570,000. The catalog contains an extensive historical essay on the use of cigar store figures and trade signs in American commerce and Louisville’s prominent place in the tobacco industry in the mid- and late-Nineteenth Century. It was written by Bob Shaw, who has researched and written extensively on folk art and decoys.

At $570,000, the undisputed star of the sale was this 83-inch-tall cigar store Indian princess with a well-documented provenance. It had stood in front of a store in Louisville, Ky., for perhaps a hundred years before being sold in 1974. The catalog, which devotes six pages to her, has a great deal of information on the carving and speculates that it may have been made by Samuel Robb or Thomas Brooks. The cigar store princess is shown standing in front of this Louisville, Ky., store.

The cigar store princess was not the only item in the sale to bring more than $100,000. A pair of hollow carved goose decoys, sold separately, made by Mandt Homme, an accomplished Wisconsin carver in the second quarter of the Twentieth Century, each sold for well over that figure. Homme was especially well regarded for his detailed feather curving, as seen on this pair. The first one sold brought $156,000 and the second a bit less, bringing $144,000. Both were in original paint with only minor imperfections. Homme primarily carved decoys for his own use, and it’s estimated that he produced only about 100 in total. He carved this pair in 1938 and entered them in a Milwaukee carving contest where they won top honors. He traded them to his good friend, Dr A.T. Shearer, for a “hound” that he liked. There were three other Homme decoys in the sale, including a mallard hen that sold for $27,600. All five had descended in the Shearer family.

Finishing just under a six-figure price was another hollow carved goose decoy attributed to Hog Island, Va., carver Eli Doughty. With relief-carved wing tips, a slightly turned and down-looking head, it brought $96,000. This decoy is pictured in American Primitive – Discoveries in Folk Sculpture by Roger Ricco and Frank Maresca. Other decoys carved by members of the Doughty family included a folky brant, which realized $27,000. These were just two of many decoys and related items in the sale from the collection of Charlie Hunter III, who died earlier this year and who had begun collecting decoys in the 1980s, with an emphasis on decoys made in Virginia, his home state, and Maryland’s eastern shore. Hunter’s collection was not limited to Southern decoys; he also owned a Canada goose made by George Skerry, Prince Edward Island, Canada. In an unusual preening pose with a raised left wing, it went out for $52,800, well over the estimate.

Several of Hunter’s other Southern decoys did well. A pair of pintails made early in the Twentieth Century by Doug Jester, Chincoteague, an island off the eastern coast of Virginia, brought $18,300. From the same island, an important back preening Canada goose, this one made by Miles Hancock at about the same time period, sold for $17,400. It was constructed from cotton wood with tack eyes. The head is stretched backwards. A very folky Canada goose with a well-worn surface, made in the late Nineteenth Century by Lee Dudley, Knott’s Island, N.C., and pictured in Southern Decoys by Henry Fleckenstein Jr earned $84,000. The wings are relief carved and it has an extended tail. The catalog states that it is “possibly the only known example with the original head and neck.” Other Southern decoys included examples by Captain Robert Andrews, Alvira Wright, the Ward Brothers and several more.

Second only to the Indian princess, finishing at $156,000, this Canada goose was made by Mandt Homme, an accomplished Wisconsin carver in the second quarter of the Twentieth Century. It was one of an award-winning pair he made in 1936 and traded for a dog he liked. The mate sold for $144,000.

As always, a number of decoys by New England carvers did well. A hollow-carved Eskimo curlew made by a member of the Folger family on Nantucket in the late Nineteenth Century reached $60,000. It had wings carved in relief and a split tail. A yellowlegs (a large sandpiper) with strong original paint, made by Lathrop Holmes, Kingston, Mass., reached $39,000. There were about 40 carvings by Elmer Crowell, including a rare carving of a pickerel on a 21-inch plaque. It’s signed and dated 1936. Another rare Crowell was a full-sized brant with crossed wingtips and good paint, which realized $13,200. Crowell miniatures ranged from $840 to $3,600. An unusual seagull carving by Portland, Maine, lighthouse keeper Gus Wilson sold for $2,100. Several layers of paint had worn away, leaving a nicely weathered surface. One of Wilson’s hollow-carved eider drakes brought $1,500. A yellowlegs by Seabrook, N.H., native George Boyd, with mostly original paint, realized $2,400. There were many more.

Mentioned above was a fish carving by Elmer Crowell, but by far the most desirable fish and other animal carvings are those done by Oscar Peterson of Cadillac, Mich. One of his works, a rare relief-carved 31-inch fish plaque with a “flip tail” brook trout, earned $84,000. Carved in detail, as the fish was leaping to a butterfly lure, it was brightly painted and the fish was leaping from a carved, watery background. A lake trout trade sign that hung in a fishmonger’s store in Cadillac went out for $60,000. There were 25 Peterson carvings in the sale, including some of his animals, such as a happy 8-inch-long chipmunk nibbling on an acorn, which sold for $6,600.

The sale included more than decoys, decorative carvings and miniatures. There were guns used by market gunners, firearms-related advertising, Audubon prints and several sporting paintings, each examined under black light, led by an oil on canvas, “Three Irish Setters,” by Edmund Henry Osthaus (1858-1928). This painting was inspired by the actions and pose of Osthaus’ dog, Mack, on a ruffed grouse hunting trip, and it sold for $66,000. There was a large painting, also of hunting dogs, done by Percival Rousseau (1859-1937). It depicted two setters on point at the edge of a woodland, and it finished at $33,000, well over the estimate. Also exceeding the estimate, bringing $28,800, was a watercolor by Frank Benson (1862-1951). It was signed and dated 1894 and titled “For the Boat House.” It depicted two hunters shooting coot from a dory.

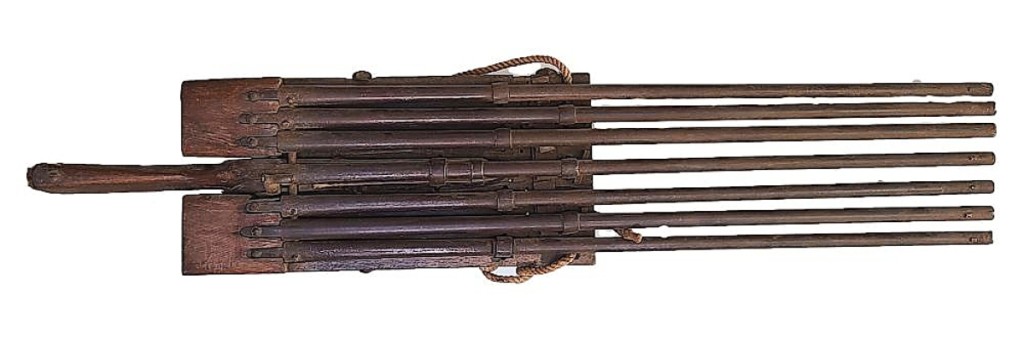

Guns such as this, used by market gunners until they were outlawed, were capable of killing dozens, if not more, birds at one time, and few have survived. This rare, seven-barrel percussion battery gun has barrels that measure ¾-inch in diameter. The barrels are 42 inches long and the gun earned $21,000. Some, probably this one included, were cumbersome, homemade but effective weapons, and the sale catalog includes an extensive discussion of these guns. There were numerous accidents recorded by men using these mass killing weapons. Some market gunners mounted their weapons directly onto their boats. They were almost as dangerous to those using them as they were to the birds. Set-ups like this were usually used to sneak up on a flock resting on the water.

The term “market gunner,” used frequently when discussing decoys and their makers, was the subject of an informative three-page article in the catalog. In short, market gunners used large bore, or multiple shotguns of various configurations, some weighing more than 100 pounds and some attached to small boats, to increase the number of birds that could be killed at one time. This sale included a selection of these guns from the Hunter collection. The article quotes a hunter working the Holland Island area of Chesapeake Bay saying that one night, working with three friends, they killed more than a thousand ducks. “By morning, we had killed over 1,000 ducks. They brought $3.50 a pair in Baltimore, and it was the best night’s work we’d ever done.” Use of these guns was restricted starting as early as 1832, but the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918 effectively ended the practice. One example in the sale, a shotgun with seven barrels, sold for $21,000. Most of the others brought between $1,500 and $3,500. The Shelburne Museum and other museums have mounted exhibitions of this interesting phase of duck hunting.

A few days after the sale, Jon Deeter said, “The thing I liked most about this sale was that we are able to do it live for the first time in two years. That was exciting – decoy collectors are a social group and getting together with other collectors is good for everybody. We had about 150-200 folks in the room for this sale, and everyone had a good time. Several people said they were glad to be able to see old friends again. Prices were fine. The Charlie Hunter collection had outstanding Southern birds that had been off the market for years. Collectors took advantage of the availability of some of those decoys. The Oscar Peterson carvings are increasing in value, especially for the best examples, and they’re being accepted as folk art, as they should be. We’ve been writing about his life and skill in the past few catalogs, and I think that’s helped people to evaluate and appreciate his work. We have some good things for our next auction, which will be live, in late April.”

Prices given include the buyer’s premium as stated by the auction house. For information, www.guyetteanddeeter.com or 410-745-0485.