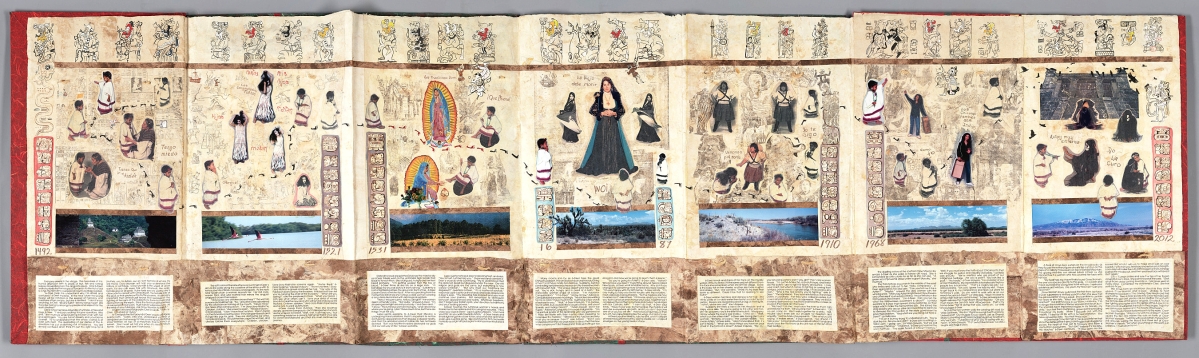

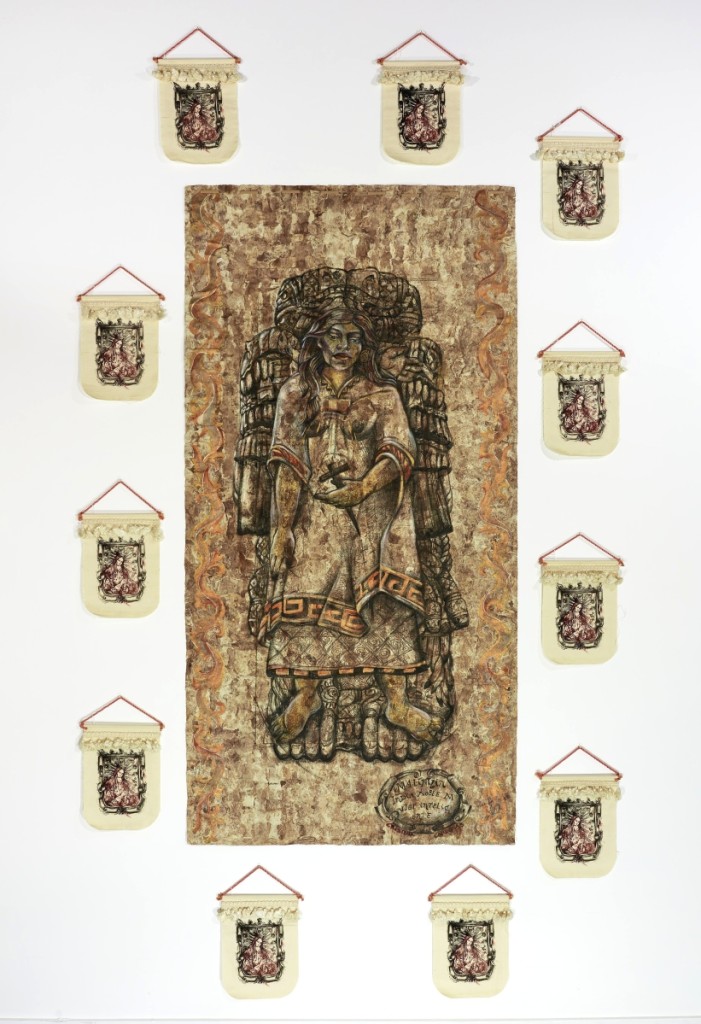

“Codex #2 Delilah: Six Deer: A Journey from Mechica to Chicana” by Delilah Montoya, 1992-95. Painted amate paper on board, photographs, and string. Department of Special Collections, Stanford Libraries. ©Delilah Montoya. Courtesy Department of Special Collections, Stanford Libraries.

By Kristin Nord

DENVER, COLO. – Very little is known about the Nahua girl, believed to be between 11 and 16 years of age when she became Hernán Cortés’ translator and cultural interpreter.

One of the great ironies of her life history is the fact that a woman celebrated for her linguistic skills should have a succession of men interpreting for her, for good or for ill, for some 500 years. Now, in a stunning and provocative exhibition curated by Victoria I. Lyall, the Frederick and Jan Mayer curator, art of the ancient Americas at the Denver Art Museum (DAM), and Terezita Romo and Matthew H. Robb, independent curators, “La Malinche” comes alive in glory and continued controversy through Indigenous pictorial histories, tapestries, sculptures, paintings and poetry.

She was known by many names – Malintzin, the Nahuatic honorific; Doña Marina, her Spanish baptismal name, and Malinche, the vernacular form of Malintzin.

In the memoirs of Bernal Diaz del Castillo, a soldier who accompanied Cortés on his campaign, she is portrayed as a wronged Indigenous noblewoman who had been stripped of her inheritance but whose intelligence and beauty secured her fate.

“La Malinche” by Emanuel Martinez, 1987. Bronze. The Abarca Family Collection, Denver. ©Emanuel Martinez. Photography ©Denver Art Museum.

In Castillo’s telling, she had come from the region of Coatzacoalcos on the Gulf of Mexico but was sold by her mother to Indian traders after her father died, eventually becoming a sex slave awarded to the Spanish by the Chontal Maya after they were defeated in battle in 1519.

Malinche’s place in history was predicated on her ability to speak multiple Indigenous languages and Spanish; as an interpreter she played an important role in major and minor transactions, negotiations and conflicts between the Spanish and the Indigenous populations of Mexico. With her help, Cortés was able to kill the Aztec leader, ushering in a new era of Spanish domination. Later she bore a son, Martín, with Cortés, who is identified as the first mestizo.

Beyond the bare bones of this narrative, Malinche’s persona was tarnished for generations by a succession of male writers, most notably the poet Octavio Paz, who cast her as a towering Eve in direct opposition to the Virgin of Guadalupe, Mexico’s other archetypal matriarch.

In Paz’s rendering, Malinche was an opportunistic whore who single-handedly brought about the doom of her people. Yet he and many other authors notably omit, Lyall notes, that La Malinche was a slave, compelled to accede to Cortés’ wishes or risk death at his hands.

After the conquest of the Aztec Empire was completed, she continued to live with Cortés as his slave and interpreter – though once again, Lyall notes, it’s impossible to know whether this was forced or consensual. She later married one of Cortés’ captains and was thereby elevated to the status of a free Spanish noblewoman, with the rights and privileges of that class. She bore a daughter, Maria, and was believed to have died during a smallpox outbreak when her children were still young. No historic documents of her birth or death survive, though her death is believed to have occurred between 1527 and 1530.

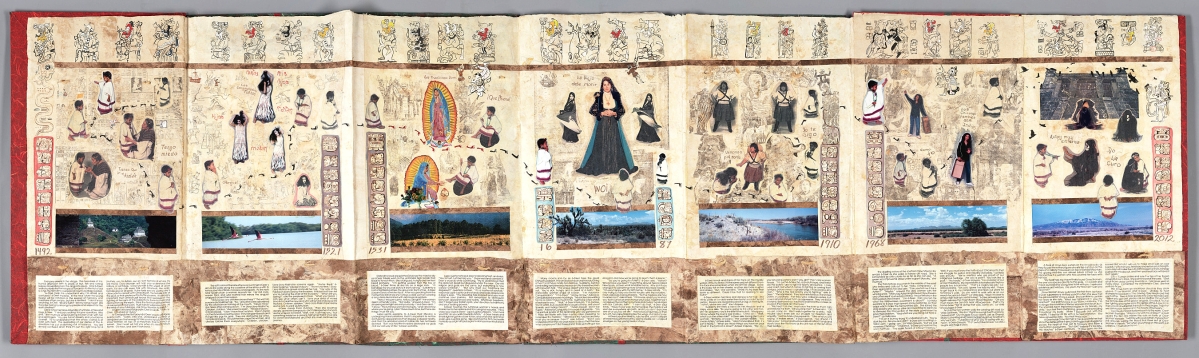

“La Traición de Malinche (Malinche’s betrayal)” by Teddy Sandoval, 1993. Watercolor on treated canvas. Courtesy of Paul Polubinskas, Estate of Teddy Sandoval. Photo courtesy of Elon Schoenholz Photography.

To this day Mexicans and Mexican Americans have deeply mixed feelings about Malinche. For some, Cortés and Malinche’s union spawned a troubled mixed-race legacy. And fascinatingly, until the Twentieth Century it has been male artists, scholars and activists who have forcefully appropriated Malinche’s story and embellished it to further their cultural and political agendas.

Whereas this young indigenous woman initially appears prominently in the early Indigenous chronicles of the Conquest, by the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries her role has been greatly diminished in Spanish accounts. By the early Twentieth Century, when Mexico won its independence from Spain, Malinche appears as a full-fledged villain in Mexico’s creation story. By now her name has become a slur – Malinchista – and her mixed-race union with Cortés has been seen as the source of Mexico’s existential suffering. In Octavio Paz’s grim assessment, the Cortés/Malinche union and the arrival of their illegitimate son, Martín, sealed Mexico’s fate; forever dooming the new nation to repeated cycles of conquest, violation and revolution.

“Traitor, Survivor, Icon: The Legacy of La Malinche” includes 68 works by 38 artists, including two new commissions – a map of Malinche’s life by L.A.-based Chicana artist Sandy Rodriguez and a Twenty-First Century interpretation of La Malinche’s attire by Mexican fashion designer Carla Fernández. DAM has secured significant loans from the Brooklyn Museum, the Blanton Museum, the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Phoenix Museum of Art, and Mexican lenders – Museo Soumaya, the Museo Nacional de Antropologia, the Museo del Calendario Mexicano and the Galería de Arte Mexicano. This traveling exhibition will be modified when it moves to the Albuquerque Museum and the San Antonio Museum of Art to reflect each region’s version of this Mexican American story.

As the exhibition unfolds, its curators have not hesitated to challenge longstanding, but erroneous, assumptions.

For one thing, Lyall notes, there is no historical evidence that Malinche was Cortés’ willing lover; and one might argue that Malinche, who was still a teenager, plied her linguistic talents and tactical skills for her own survival.

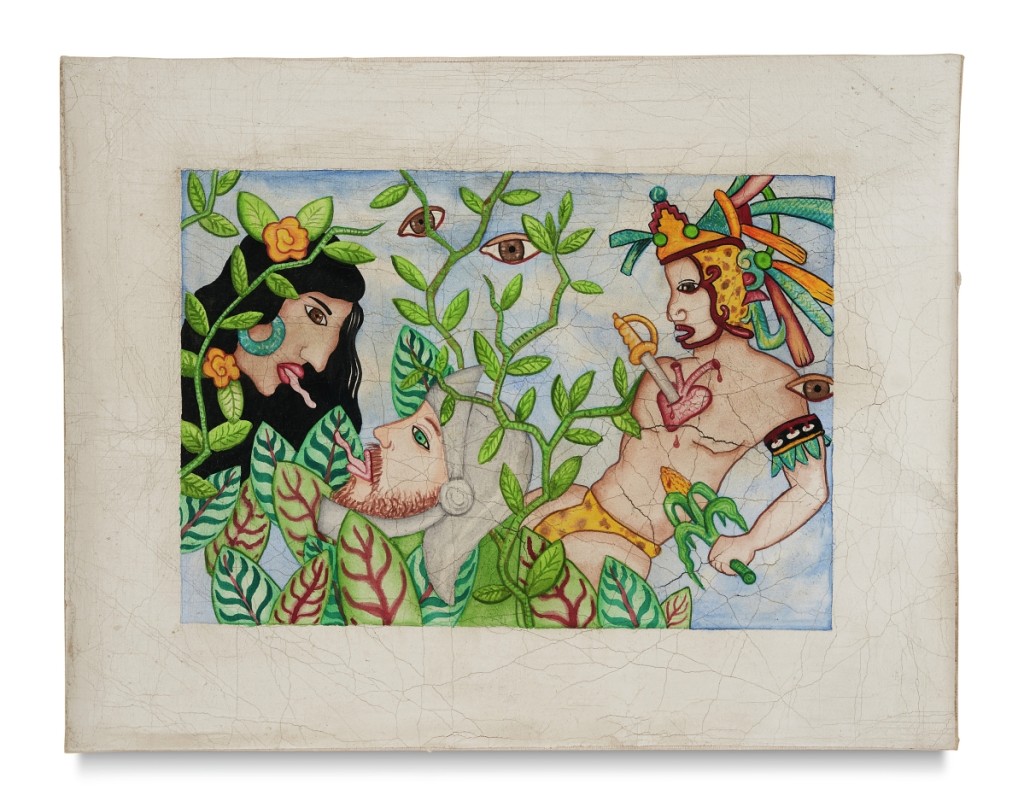

“La Malinche Tenía Sus Razones (La Malinche had her reasons)” by Cecilia Álvarez, 1995. Acrylic paint on amate paper. Courtesy of the artist. ©Cecilia Concepción Álvarez.

There are many remarkable works in this exhibition – among them Antonio Ruíz’s surrealist painting, “El Sueño de la Malinche,” which transforms a sleeping Malinche’s body into a site of battle and colonization; and Cecilia Alvarez’s “La Malinche Tenia Sus Razones” (1995), moving portrait of a tearful La Malinche flanked by a polyptych that details her enslavement and trade to Cortés. Alfredo Ramos Martinez (1940) conjures “La Malinche (Young Girl of Yalala, Oaxaca)” as a woman with seemingly mythical properties. Leslie Tillett’s “Tapestry of the Conquest of Mexico” (1965-1977) is a 104-foot masterpiece with 231 embroidered scenes, including almost 1,500 human figures, which depicts the Spanish conquest of the Aztecs from the points of view of both the victors and the vanquished.

In addition, several thought-provoking collages probe the roles and attitudes projected upon Malinche over time. One of note is Mercedes Gertz’s “Guadinche” (2012), which superimposes images of Malinche and the Virgin of Guadalupe in layers.

It seems fitting that this exhibition should make its debut in Denver, the seat of El Movimiento, which fought successfully to empower its Mexican American populace through a chicanismo or cultural nationalism in the late 1960s. The slur, Chicano, became a fierce identifier as murals sprouted throughout the city, and Chicana feminists began to reclaim and recontextualize La Malinche’s story. It was a time for Mexican American women to rebel against what they proclaimed was the double victimization of the dominant Anglo society at and their own Mexican/Chicano communities.

In “Chicana: Contemporary Reclamations,” the final section of the exhibition, its co-curators take obvious pleasure in deconstructing what they perceive as gross distortions of the Malinche archetype. By the 1990s and the Columbus Quincentenary, many Chicana artists were challenging the racist and patriarchal constructions of this mythical figure and beginning to create images that underscored her relevance as a cultural hero, Lyall said.

Chicanas pursued college educations, sought leadership positions and challenged established norms. And they did so, noting with dismay, in the face of racial and female subjugation that was continuing to thwart progress. Some artists began creating portraits of family and community women that they perceived to be Malinche likenesses. Historically vilified, Malinche was now becoming a figure of perseverance and survival.

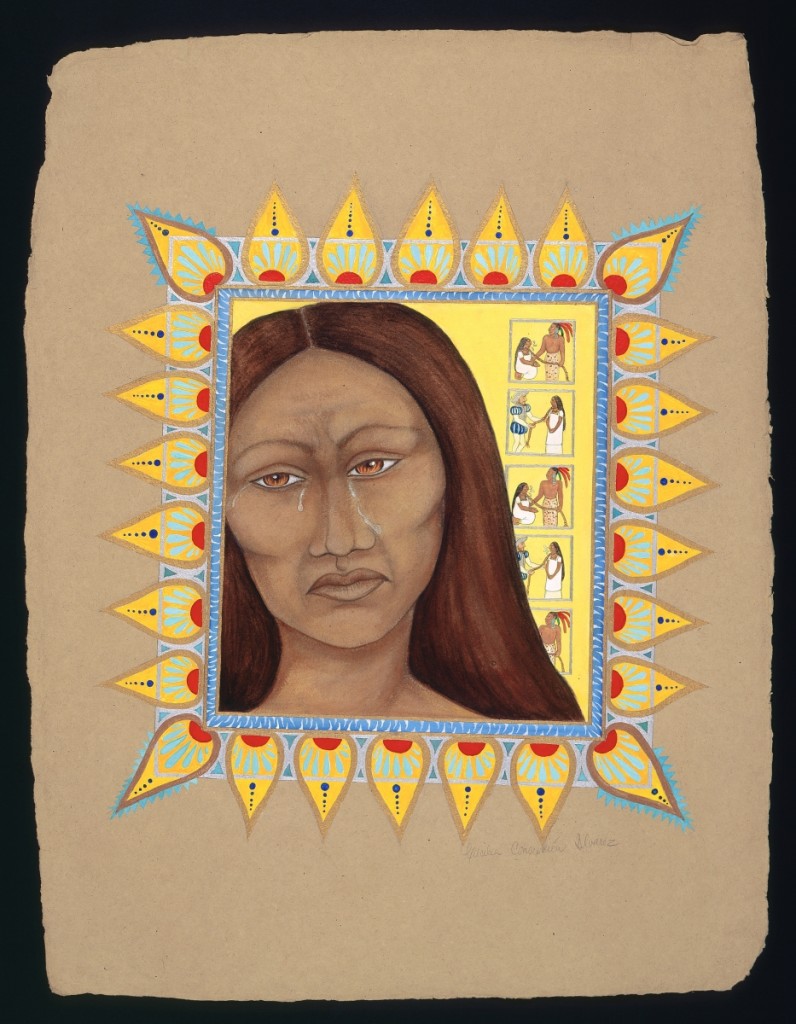

“Malinche, Coatlicue y Virgen de los Remedios” by Cristina Cárdenas, 1992. Ink on amate paper and cloth. The Mexican Museum, San Francisco. ©Cristina Cárdenas. Photo by Mark Andrew Wilson.

Activist Chicanos, notably Denver’s celebrated muralist, Emanuel Martínez, were depicting Malinche in a more positive light. In one of his bronzes we encounter Malinche as a full-bodied free spirit.

Martínez’s daughter, Lucha Martínez de Luna, the associate curator of Hispano, Chicano, Latino History and Culture at History Colorado, grew up in a home filled with such images. While many Mexican American families have Jesús Helguera calendars with Mexican American women as telenovela starlets on their walls, Martínez grew up in a home in which Malinche appeared as an indigenous warrior woman.

A separate exhibition, titled “Smoking Mirrors: Visual Histories of Identity, Resistance and Resilience,” running through February 26 at Museo de Las Americas, makes a marvelous companion stop for museumgoers wishing to dig deeper into Twentieth Century Denver history. From Emanuel Martínez’s first mural, which he painted at La Alma Lincoln Park, Martínez went on to paint hundreds of murals in the city’s Black and Latinx neighborhoods. His daughter, who is also an archeologist, and founder and director of the Chicano’s Murals of Colorado Project, is seeking to preserve these remnants of Chicano history threatened by gentrification.

It would seem the world is far from done with Malinche, or with culture and gender wars, for that matter.

“I expect that 90 percent of the people who visit the museum will not realize who Malinche is, but once they hear the story they’ll be hooked,” Lyall promises.

“Traitor, Survivor, Icon: The Legacy of La Malinche” is running through May 28. The Denver Art Museum is at 100 West 14th Ave Parkway. For information, 720-865-5000 or www.denverartmuseum.org.