By James D. Balestrieri

LONDON – “The world of Stonehenge,” now on view at the British Museum, is perhaps the first comprehensive exhibition to examine this focal human creation, not only in the context of the greater complex of contiguous and coterminous settlements and monuments, but over the course of its long history and shifts in culture. Because Stonehenge stands at so great a remove from our world, having been constructed some 4,500 years ago, its “meaning” has become a locus of speculation and projection, centered in large measure around the summer and winter solstices. “The world of Stonehenge,” wisely, and with great care, quashes the more egregious of these and qualifies its conclusions with numerous caveats. With no written record, there is much that we don’t know about Stonehenge. There is much more that we cannot know. Not for certain. In fact, recent excavations have shown that the use of the site as a gathering place and memorial dates back some 10,000 years, to the end of the last Ice Age, the receding of the great glaciers, and the gradual warming of the world. “Why there, in that place?” is the ultimate unanswerable question that overarches the exhibition.

For much of its history since the first excavations in the Eighteenth Century, Stonehenge was seen as a singular monument with barrows scattered around it. But in the intervening centuries, as archaeology shifted from the hobby of aristocrats to the province of science, Stonehenge has emerged as the center of a sprawling complex that includes many other “henges.” Woodhenge, with its concentric circles of tall oak trunks, and Seahenge’s central elements, a massive, upturned tree trunk, roots reaching for the sky, alternately concealed and revealed by the brackish tide, loom as especially spectacular in the imagination. As an example, not far away and connected to Stonehenge by a broad avenue – part of a network of connecting paths – the Durrington Walls settlement, which perhaps housed the artists, artisans and craftspeople who worked on the complex when the giant sarsen stones – slabs of silica-infused sandstone – were erected, may have numbered up to a thousand dwellings.

What emerges from the exhibition is a series of oppositional concepts that the idea – and power – of Stonehenge managed to keep in balance through hundreds of generations of cultural adaptation.

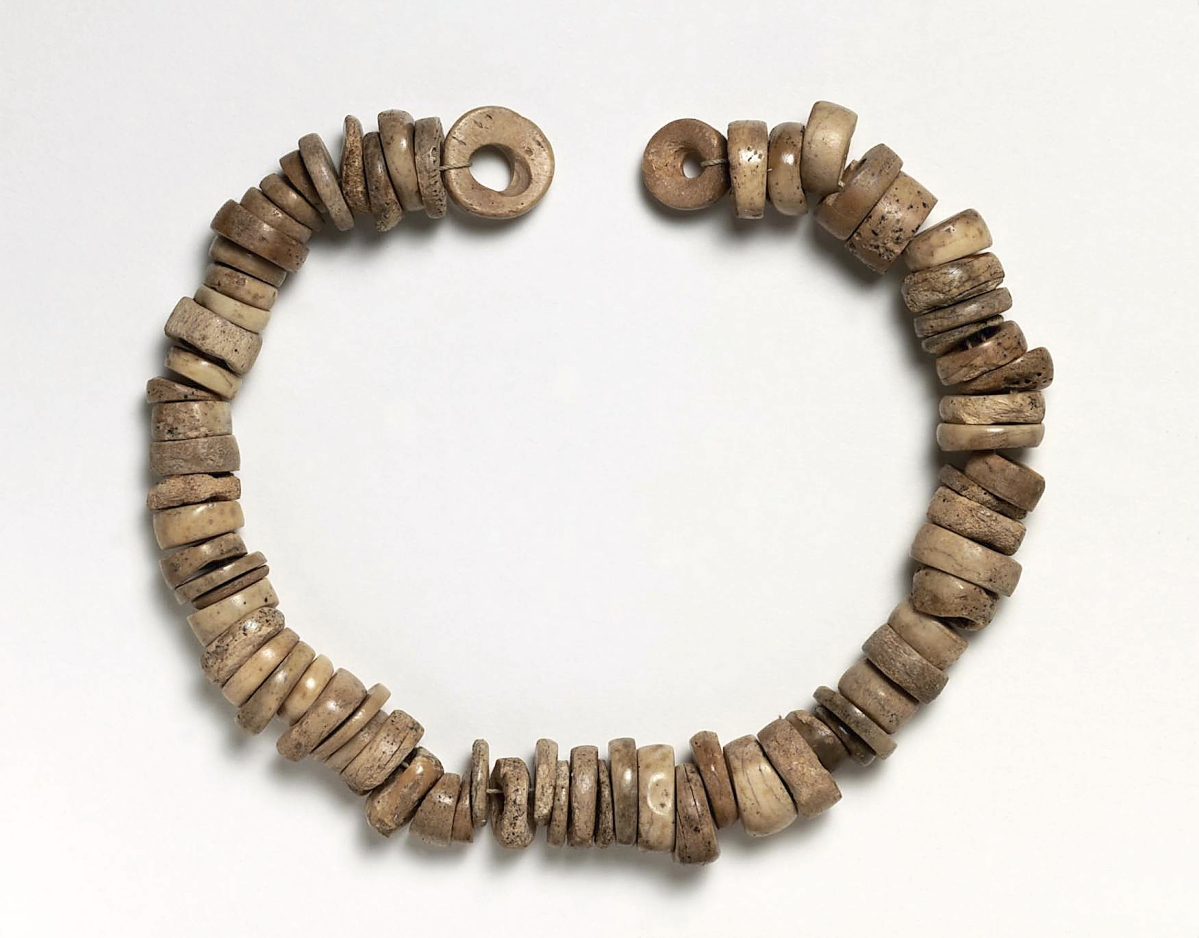

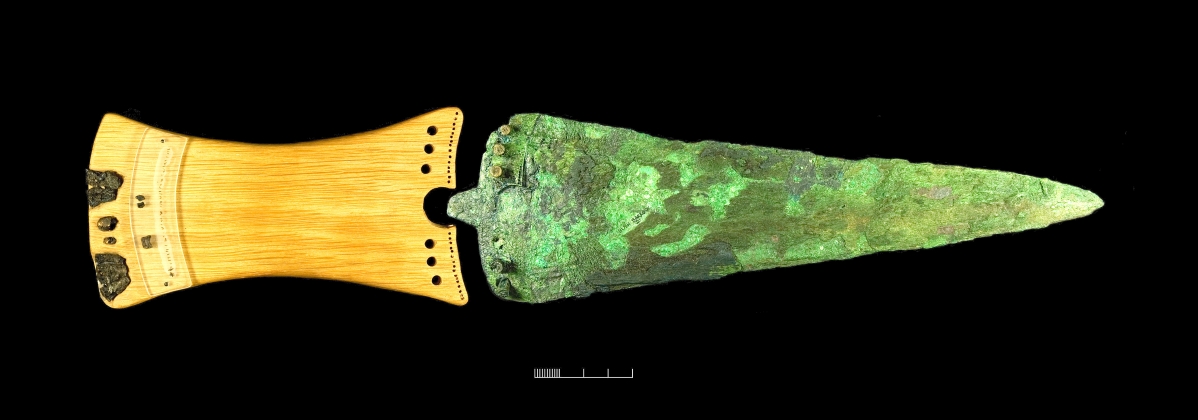

Burial above ground, on platforms first and then in communal mounds, which are both above and underground, dominate at first. Then, as people migrated from the continent to Britain, they brought their burial practices with them – single and family interments beneath the earth. Early burials featured disarticulated and reassembled body parts, possibly suggesting community as a single organism. Grave burials that gradually succeed these revere the individual body and are accompanied by objects that identified the person in life as well as objects, such as projectile points, that the spirit will need in the afterlife. Later, objects of beauty and power will be buried without an attendant body. Some of these, knives and jewelry, will be deliberately broken and bent before they are buried, as if their power has been sacrificed with their materiality. From an afterlife in the sky to one below ground, from communal interment to individual burial, the world of Stonehenge accommodated these sea changes in spirituality.

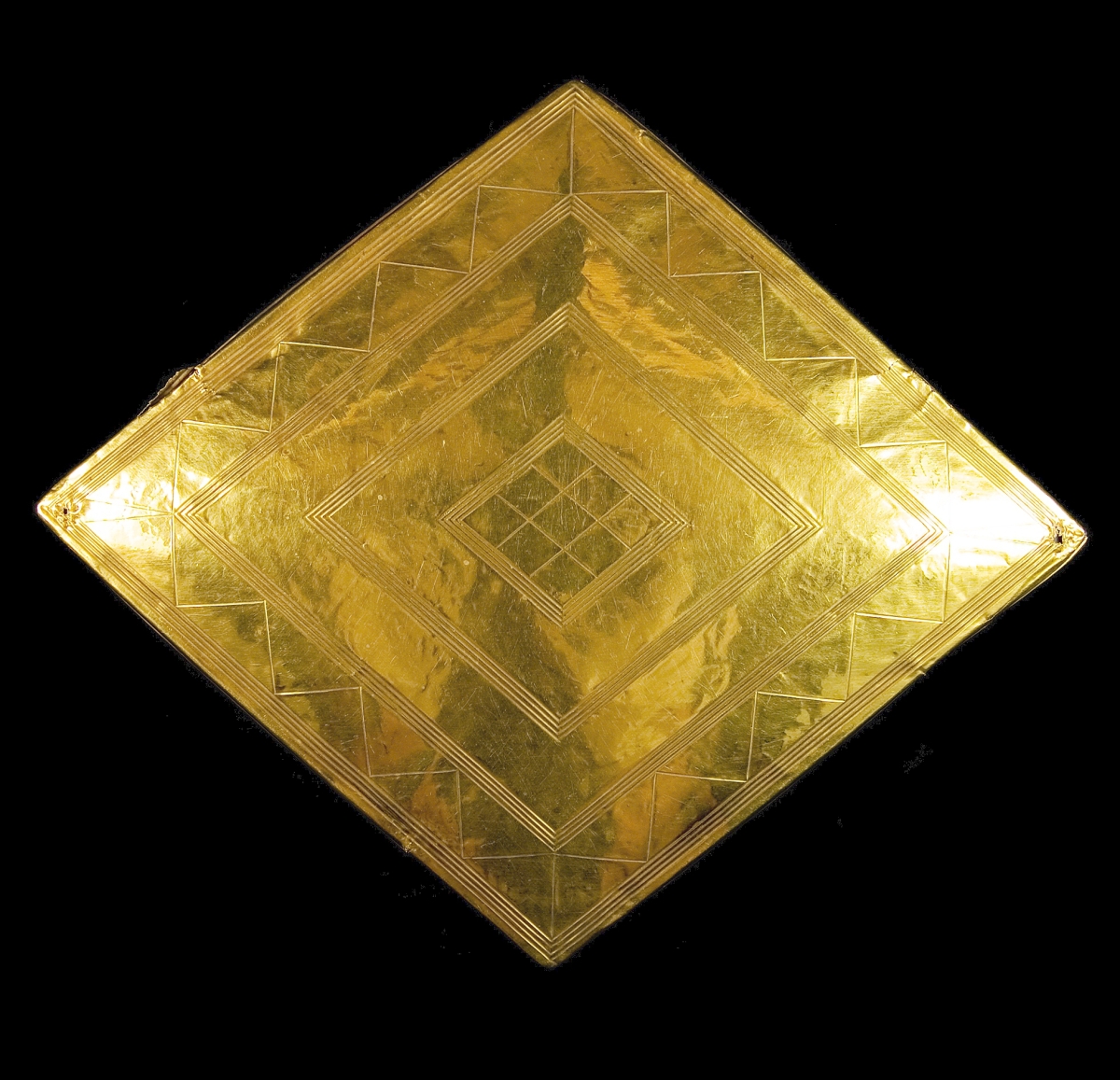

Lunula, From Blessington, County Wicklow, Republic of Ireland, 2400-2000 BCE. ©The Trustees of the British Museum.

Immigrants from the continent brought their ways of life as farmers and herders and transformed Britain’s hunter-gatherer society. Culture changed as stone – with jadeite from the Italian mountains as a highly prized and traded material – gave way to copper, which came to Ireland via Portugal. With the discovery of tin in Cornwall and the addition of tin to copper, bronze was forged and another age began. Gold, that seemed to capture the sun, made the iconography of the solstice at Stonehenge portable. All these were special materials, not easily obtained, not easily worked. Objects made from them were relatively rare. It was the mining, treating and tempering of iron, which was ubiquitous, that ushered in an age that leads, recognizably, to our own, in which metal could be shaped to plough the earth or slay an enemy.

But that is the end of the story. What is interesting is that the influx of immigrants from the continent to Britain does not appear to have resulted in conflict. Perhaps cultural similarities were greater than differences. The exhibition examines sites from the Orkneys to Italy and finds congruences in iconography and cultural practices across these great distances. Perhaps the populations were small enough to accommodate newcomers. Perhaps new ways of making pottery and handling metal were welcomed. Perhaps curiosity and trade triumphed over suspicion. Perhaps the people of the Stonehenge complex struck a balance between commemoration and celebration, between reverence and great feasts, a schedule that left no time for war. As the catalog suggests, the act of designing, building, altering and maintaining the monuments may have been even more important in binding the community to the site, and to one another, than their ceremonial functions. The decision to move giant stones from the Welsh mountains to the Stonehenge site in Wiltshire, for example, must have been as momentous as the task was monumental. It would certainly have kept people busy – and working together.

In surveying the exhibition, you get the sense that the people of Stonehenge were simultaneously aware of their moment in time, but also, at the same time, connected to deep time. A stone axe, for example, an object that was already 1,000 years old then, was found not long ago in a Bronze Age burial. What had it meant and for how long? What did it mean that it was finally buried? Who was the man in the grave? What had he meant to his community in life? What power did he wield? Or did power reside in the axe as opposed to the man?

The range of objects in “The world of Stonehenge” and the artistry they exhibit is astounding. Of all of these, the Nebra Sky Disc is perhaps the most intriguing. Illegally unearthed in Germany in 1999, as the “oldest material depiction of cosmic phenomena in the world, it challenges deep-seated preconceptions about the astronomical knowledge of ancient communities.” (The world of Stonehenge, by Duncan Garrow and Neil Wilkin, London: British Museum, 2022, p. 144).

The green patinated background of the Nebra Sky Disc was once purple as the night sky. Elements in gold affixed to the disc represent important celestial phenomena in pictorial form.

Two moons – one crescent, one full – float among a scattering of stars, including the Pleiades, whose rhythms marked spring and fall. When the Seven Sisters disappeared over the western horizon in March, spring was near; when they reappeared in the east in October, it was time to get the harvest in.

The Nebra Sky Disc also reconciles the disparities between the solar and lunar years, as the catalog explains: “A problem arises, however, when it comes to equating the solar and lunar years. The former is eleven days longer than the latter and after three years the difference is equivalent to about a month. To bring the two calendars into harmony a rule is needed. The first written record of such a rule comes from a Babylonian cuneiform tablet dating to the Seventh or Sixth Centuries BCE, which advises to add a leap month every third year if no new moon appears next to the Pleiades in the spring but rather a crescent moon a few days old. That arrangement of heavenly bodies is precisely what the Sky Disc seems to show, reflecting an ingenious materialisation [sic] of a complex astronomical and calendrical rule without the need for writing.” (The world of Stonehenge, by Duncan Garrow and Neil Wilkin, London: British Museum, 2022, pp. 145-47)

Further, golden arcs added at right and left – the left arc is missing – form visual representations of the summer and winter solstices when bisecting lines are drawn from their ends through the middle of the disc.

At some point, the arc at the bottom of the disc, an abstraction of the sun ship that appears as a symbol across northern Europe, was added, connecting astronomy to mythology, and holes at the edges of the disc that suggest that it may have been worn or borne aloft in procession.

What lingers after considering all that “The world of Stonehenge” has to offer is the relative absence of weaponry and evidence of organized warfare over the course of centuries, not only in Britain, but throughout Northwestern Europe. As late as 325 BCE, the geographer Pythias, who set out from the bustling port of Massalia – Marseilles – encountered no hostility that we know of as he sailed up the Spanish and French coasts, explored much of Britain, then continued on to the Hebrides – and possibly Iceland – and returned home by way of Scandinavia. This must have been a revelation to a citizen of a Hellenistic empire that seethed with ambition from Iberia to India.

Bronze twin horse–snake hybrid from hoard, Kallerup, Thy, Jutland, Denmark, 1200–1000 BCE. CC-BY-SA, Søren Greve, National Museum of Denmark/Ofret Museum.

Perhaps new gods displaced the gods of Stonehenge. Perhaps the old rituals changed to such an extent that they lost their meanings. Perhaps the fertility of the land gave out and the gods no longer responded to the old propitiations. Perhaps new stratifications in society gave rise to the necessity to form new allegiances to living leaders of cultural elites. Perhaps people simply drifted away from Stonehenge. Venerations succeed one another just as generations do. Yet, as we think about our relationship to the natural world and how to redress the serious imbalances we ourselves have created – if, that is, we can bring ourselves to do it – the example of Stonehenge and the people who saw it as a place of balance between life and afterlife, between sky and land and sea, between the celestial and the communal, is one that might be worth revisiting and getting closer to, even as it recedes in time away from us.

Let me leave you with this: many of the objects in “The world of Stonehenge” were first discovered by detectorists and then studied and displayed in museums. Our interests lie in material value – monetary value, the value of discovery and fame, the value of semantic and historic significance. We want to find things and own things; we want to find out about them and own their meanings. On the other hand, the interests of those who crafted these objects seem rather to have lain in the mysteries of creation, in their utility – whether practical, spiritual, or both – and then in the sacrificial return of the objects, once their utility was exhausted, to the elements they were wrested from. The people of Stonehenge seemed to feel that the things they made were borrowed, made to last but also made to change and be changed, and that they themselves were brief incarnations – caretakers, in a way – in cycles of seasons inside a continuum of deep time. Understanding these opposing world views is part of the message of Stonehenge. What humankind does with this understanding is perhaps one of the most pressing questions of our age.

“The world of Stonehenge” will be on view at the British Museum until July 17.

The British Museum is on Great Russell Street. For information, www.britishmuseum.org.